Handbook on Briefs and Oral Arguments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

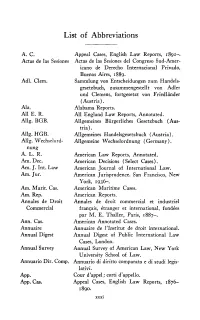

List of Abbreviations

List of Abbreviations A. C. Appeal Cases, English Law Reports, r8gr-. Aetas de las Sesiones Aetas de las Sesiones del Congreso Sud-Amer icano de Derecho Internacional Privado, Buenos Aires, r88g. Adl. Clem. Sammlung von Entscheidungen zum Handels gesetzbuch, zusammengestellt von Adler und Clemens, fortgesetzt von Friedlander (Austria). Ala. Alabama Reports. All E. R. All England Law Reports, Annotated. Allg. BGB. Allgemeines Biirgerliches Gesetzbuch (Aus- tria). Allg. HGB. Allgemeines Handelsgesetzbuch (Austria). All g. W echselord- Allgemeine Wechselordnung (Germany). nung A. L. R. American Law Reports, Annotated. Am. Dec. American Decisions ( Select Cases) . Am. J. Int. Law American Journal of International Law. Am. Jur. American Jurisprudence. San Francisco, New York, 1936-. Am. Marit. Cas. American Maritime Cases. Am. Rep. American Reports. Annales de Droit Annales de droit commercial et industriel Commercial fran~ais, etranger et international, fondees par M. E. Thaller, Paris, r887-. Ann. Cas. American Annotated Cases. Annuaire Annuaire de l'Institut de droit international. Annual Digest Annual Digest of Public International Law Cases, London. Annual Survey Annual Survey of American Law, New York University School of Law. Annuario Dir. Camp. Annuario di diritto comparato e di studi legis lativi. App. Cour d'appel; corti d'appello. App. Cas. Appeal Cases, English Law Reports, 1876- r8go. xxxi XXXll LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS App. D.C. Appeal Cases, District of Columbia. App. Div. New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division Reports. Arch. Civ. Prax. Archiv fiir die civilistische Praxis (Germany) . Arch. Jud. Archivo judiciario (Brazil). Ariz. Arizona Reports. Ark. Arkansas Reports. Asp. Marit. Cas. Aspinall's Maritime Cases. Atl. Atlantic Reporter, National Reporter System (United States). -

Indiana Law Journal

Indiana Law Journal Volume 10 Issue 5 Article 8 2-1935 Indiana Bar Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation (1935) "Indiana Bar," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 10 : Iss. 5 , Article 8. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol10/iss5/8 This Special Feature is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INDIANA BAR A Message From the President At the time this message is written (February 2nd) the decision of the Supreme Court on the validity of the Bar Admission Act of 1931 and the method of amending the constitution of Indiana is but a few days old. The removal of the provision of the constitution providing that "every person of good moral character, being a voter, shall be entitled to admission to practice law in all courts of justice" gives the lawyers of Indiana an opportunity to raise the standards of the profession free from the limitations of this unwise restriction. It will not be necessary to change the legislative program of the association by reason of the decision, and the three bills approved by the association have been introduced as follows: H. B. 142, Procedural Bill restoring rule making power to Supreme Court H. B. 141, Judicial Council Bill H. B. 128, Integrated Bar Bill The usual opposition has developed, but the endorsement by all three of the Indianapolis newspapers as well as by many others in the State, the ap- proval of the bills in the Governor's message to the General Assembly and his explanation and endorsement of them over the radio, and friendly gestures from other sources have greatly encouraged the Legislative Committee. -

Comparative Negligence - Panacea Or Pandora's Box 1 J

UIC Law Review Volume 1 Issue 2 Article 3 Winter 1968 Comparative Negligence - Panacea or Pandora's Box 1 J. Marshall J. of Prac. & Proc. 270 (1968) Kevin T. Martin Richard J. Phelan John H. Scheid Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kevin T. Martin, Comparative Negligence - Panacea or Pandora's Box 1 J. Marshall J. of Prac. & Proc. 270 (1968) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol1/iss2/3 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTARY COMPARATIVE NEGLIGENCE - PANACEA OR PANDORA'S BOX? By RICHARD J. PHELAN* KEVIN MARTINt JOHN SCHEID$ In Maki v. Frelk' the Illinois Appellate Court held that a complaint alleging "that at times relevant hereto if there was any negligence on the part of the plaintiff or the plaintiff's decedent it was less than the negligence of the defendant, Calvin Frelk, when compared, ' 2 will withstand a motion to dismiss for failure to state a cause of action, even though the complaint admits that the plain- tiff may have been guilty of a lesser degree of negligence which proximately contributed to his injuries. Prior to this decision, the complaint would have been dismissed. Considering the his- tory of the case, this decision may be a prelude to the Illinois Supreme Court's adoption of a comparative negligence system in Illinois.3 The Maki case was initially appealed to the Illinois Supreme Court which found no constitutional issues on direct appeal but transferred the case to the appellate court to consider "the ques- tion of whether, as a mzatter of justice and public policy, the rule should be changed.' ' 4 The appellate court, in reaching its decision, reviewed the arguments made by the proponents and opponents of comparative negligence. -

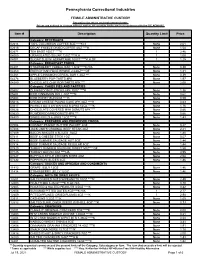

FEMALE ADMINISTRATIVE CUSTODY See Policy for Return and Replacement Terms

Pennsylvania Correctional Industries FEMALE ADMINISTRATIVE CUSTODY See policy for return and replacement terms. Prices are subject to change without notice. All quantity limits are in accordance with the DC ADM-815. Item # Description Quantity Limit Price Category: BEVERAGES 02614 100% COLUMBIAN COFFEE 5OZ ****K,H None 2.61 02616 DECAF FREEZE DRIED COFFEE 4OZ ****K None 1.54 02671 TEA BAGS 100CT ****K 1 2.46 04000 GRANULATED SUGAR 12OZ ****K,H 1 1.00 04001 SUGAR SUB W/ ASPARTAME 100CT ****K,H,GF 1 1.25 Category: BREAKFAST FOODS 04201 STRAWBERRY CEREAL BAR 1.3OZ ****K,H/A None 0.39 04260 ENERGY BAR,FDGE BRWNE 2.64OZ****GF None 1.31 04261 APPLE CINNAMON CEREAL BAR 1.3OZ *** None 0.39 04276 BLUEBERRY POP-TARTS 8PK None 1.97 04280 CHOCOLATE CHIP POP-TARTS 8PK *** None 2.00 Category: CAKES PIES AND PASTRIES 05602 DUNKIN DONUT STICKS 6PK 10OZ ****K None 1.36 05604 ICED CINNAMON ROLL 4OZ ****K None 0.62 05608 ICED HONEY BUN 6OZ ****K None 0.59 05616 CREAM CHEESE POUND CAKE 2PK 4OZ ****K None 0.63 05617 PEANUT BUTTER WAFERS 6-2PKS 12OZ ****K None 1.76 05628 CHOCOLATE COVERED MINI DONUTS 6PK *** None 0.66 05630 POWDERED MINI DONUTS 6PK *** None 0.66 06800 SWISS ROLLS 6-2PKS 12OZ ****K None 1.43 Category: PREPARED AND PRESERVED FOODS 07004 CREAMY PEANUT BUTTER PACKET 2OZ None 0.27 07406 JACK LINK'S ORIGINAL BEEF STEAK 2OZ None 2.21 07409 BACON SINGLES 6 SLICES .78OZ None 1.80 07411 BEEF & CHEESE STICK 1OZ None 0.57 07413 BEEF SUMMER SAUSAGE HOT 5OZ None 1.44 07414 BEEF SUMMER SAUSAGE REGULAR 5OZ None 1.44 07420 TURKEY SUMMER SAUSAGE SWEET 5OZ****GF -

Preference Erosion:After Hong Kong

Appendix to Chapter 2 (A2) While a large number of preference schemes are offered by developed and developing country trade partners, the main preference-giving countries for developing and least developed countries are the QUAD+: the EU, USA, Japan, Canada and Australia. The EU and USA are discussed in Chapter 2, and we begin here with some information on the others (see relevant chapters in Hoekman et al., 2009 for more detail). Japan offers GSP preferential tariff treatment to 141 developing countries, with LDCs being eligible for duty and quota free treatment on specified products. Canada imports most of its goods from the North American Free Trade Association (NAFTA) at significant margins of preference relative to MFN rates. Developing countries accounted for just under 20 per cent of its total imports in 2003, mostly under MFN, although about a quarter were subject to the General Preferential Tariff (GPT), which is generally less than half the MFN tariff. About three-quarters of preferential imports to Australia enter under devel- oping country preferences, although since 2003 a more generous LDC preference scheme has been in place. The remainder of this appendix provides details and tables to supple- ment the discussion in Chapter 2. Japan Japan’s GSP started in 1971. The current arrangements offer preferential tariff treatment to 141 developing countries, with LDCs being eligible for special preferential treatment (duty and quota free treatment on specified products). GSP treatment is granted to selected agricultural and fishery products (337 items) and industrial products (3,216 items). There is some duty free treatment under GSP for agricultural products (without ceilings), and presumption of duty free treatment for industrial products, with exceptions for sensitive items and ceilings on a significant proportion – about one-third – of indus- trial products subject to GSP treatment. -

Boxers Or Briefs Poll

Boxers Or Briefs Poll Fun Poll, Boxers or Briefs? Cast your vote and then share with your friends to get their vote. Welcome to Zity. 15%: Plain nondescript underwear. I personally prefer boxers, but they get so annoying. For women the options were briefs, bikini, shorts and thongs. Pants for sport, boxers otherwise. Seems it's a big deal with some of the younger crowd out there, (under 40) that says it's a big deal if you wear whitey tightys, boxers of briefs. 57% (647) Boxer briefs. Sam Talbot (Top Chef) - "boxers, briefs and commando" Rob Thomas (lead singer of Matchbox Twenty) Justin Timberlake (pop musician and actor) - started in briefs; switched to boxers; then to boxer briefs and sometimes commando; about boxer briefs, his current preference, he says: "like the way they hold everything together". 10 Answers. The new findings from the National Poll on Healthy Aging suggest that more physicians should routinely ask their older female patients about incontinence issues they might be experiencing. Tighty Whiteys are NOT cool (not saying you show your underwear to everyone). Share Followers 0. They also offer refastenable hook tabs and curved leg elastics like adult diapers for a fit that stays in place and helps you, or those you love, stay confident and comfortable. This comment has been removed by the author. Here's how to debrief his briefs. Kagura = 878 8. Boxers, Briefs and Battles. I in uncomplicated words switched to briefs/boxers, which ability i have were given lengthy lengthy previous from in uncomplicated words boxers to many times situations boxers, on get jointly briefs. -

Mariejo-SWIM-2022Vk.Pdf

SWIM COLLECTION SS22 SWIM MARIE JO SWIM COLLECTION The fashion collection 5 Styles overview Marie Jo 6 NEW FASHION PIECES Murcia 8 Sitges 10 Tarifa 12 Terrassa 14 Zaragoza 16 Julia 18 Camila 20 Cadiz 22 Cordoba 24 Pamplona 26 Valentina 28 Labels & patents 30 SITGES SWIMSUIT 1004630 POOLSIDE ELEGANCE BEACH FUN Stylish, more timeless looks Playful looks and styles Create an elegant silhouette Latest trends & colors SITGES MLC MURCIA YFS Seasonal CORDOBA RNF TARIFA TBS Marie Jo Swim Fashion collection PAMPLONA FRE ZARAGOSA PUN CADIZ WBL TERRASSA PPZ VALENTINA EVB JULIA ARB CAMILA RNB Spring/Summer 2022 | © Copyright NV Van de Velde STYLES OVERVIEW MARIE JO SWIM SS22 BIKINI TOPS SWIMSUIT BOTTOMS ACCESSORIES TOP TRIANGLE FULL CUP HEART SHAPE DEEP PLUNGE PUSH-UP STRAPLESS BALCONY TRIANGLE PADDED NON PADDED PADDED RIO BRIEFS FULL BRIEFS FOLD BRIEFS WAIST ROPES WIRE PADDED PADDED PADDED PADDED PADDED PADDED PUSH-UP MURCIA BEACH FUN BEACH SITGES POOLSIDE POOLSIDE ELEGANCE TARIFA BEACH FUN BEACH TERRASSA BEACH FUN BEACH ZARAGOZA BEACH FUN BEACH JULIA BEACH FUN BEACH CAMILA BEACH FUN BEACH CADIZ POOLSIDE POOLSIDE ELEGANCE CORDOBA POOLSIDE POOLSIDE ELEGANCE PAMPLONA POOLSIDE POOLSIDE ELEGANCE VALENTINA POOLSIDE POOLSIDE ELEGANCE PADDED CUPS HALTER NECK REMOVABLE STRAPS WIRELESS Spring/Summer 2022 | © Copyright NV Van de Velde RECYCLED MATERIALS Yellow Flash - YFS MURCIA 1005114 1005116 1005119 bikini triangle padded push-up bikini top heart shape padded bikini top balcony padded EUR: XS-L EUR: A 70-85 / B-D 70-90 / E 70-85 / F 70-80 EUR: B 70-90 / C-D 65-90 / E 65-85 FR: XS-L FR: A 85-100 / B-D 85-105 / E 85-100 / F 85-95 FR: B 85-105 / C-D 80-105 / E 80-100 UK: XS-L UK: A 32-38 / B-D 32-40 / E 32-38 / F 32-36 UK: B 32-40 / C-D 30-40 / E 30-38 ..................................... -

Sweports, Ltd V. Abrams

2021 IL App (1st) 200139-U FOURTH DIVISION June 30, 2021 No. 1-20-0139 NOTICE: This order was filed under Supreme Court Rule 23 and is not precedent except in the limited circumstances allowed under Rule 23(e)(1). ______________________________________________________________________________ IN THE APPELLATE COURT OF ILLINOIS FIRST JUDICIAL DISTRICT ______________________________________________________________________________ SWEPORTS, LTD., UMF CORPORATION, and ) Appeal from the GEORGE CLARKE, ) Circuit Court of ) Cook County Plaintiffs-Appellants, ) ) v. ) No. 18 L 5737 ) LEE ABRAMS, TINA WHITE, MICHAEL O’ROURKE, ) MICHAEL MOODY, O’ROURKE & MOODY, an Illinois ) Honorable law partnership, JOHN DORE, ANDREW CHENELLE, ) Thomas R. Mulroy, Jr., and NEAL WOLF, ) Judge Presiding. ) Defendants-Appellees. ) ______________________________________________________________________________ JUSTICE REYES delivered the judgment of the court. Presiding Justice Gordon and Justice Martin concurred in the judgment. ORDER ¶ 1 Held: Affirming the judgment of the circuit court of Cook County dismissing the plaintiffs’ claims for abuse of process, tortious interference with prospective economic advantage, prima facie tortious conduct, and conspiracy. ¶ 2 Plaintiffs Sweports Ltd. (Sweports), UMF Corporation (UMF), and George Clarke (Clarke) filed a complaint in the circuit court of Cook County against defendants Lee Abrams (Abrams), Tina White (White), Michael O’Rourke (O’Rourke), Michael Moody (Moody), 1-20-0139 O’Rourke & Moody, an Illinois law partnership (O&M), John Dore (Dore), Andrew Chenelle (Chenelle),1 and Neal Wolf (Wolf). The complaint alleged, in part, that the defendants engaged in vexatious litigation for the purpose of forcing the liquidation of Sweports, obtaining control of UMF, and coercing Clarke out of control of the companies. The plaintiffs asserted claims for abuse of process (count I), tortious interference with prospective economic advantage (count II), prima facie tortious conduct (count III), and conspiracy (count IV). -

Winter Hut Trip Packing List

Red Rock Recovery Center Experiential Program Packing List Winter Winter Boots Insulated, waterproof, and above the ankle. Available at Wal-Mart: Men’s Ozark Trail winter boots- $29.84 Men’s winter boots (grey moon boots)- $19.68 Women’s Ozark Trail winter boots- $46.86 Available at REI: Women’s and men’s Sorel Caribou boots- $150 Men’s Kamik William snow boot- $149.95 Men’s North Face Chilkat- $150 Available at Sportsman’s Warehouse: Women’s Northside Kathmandu boots- $74.99 Women’s Northside Bishop Boots- $54.99 Women’s Kamik Momentum- $84.99 Men’s Kamik Nation Plus boots- $79.99 Socks 2 heavy weight wool. No cotton. Available at Wal-Mart: Men’s Kodiak wool socks (2 pack)- $9.48 Men’s Dickies crew work socks- $8.77 Available at REI: REI Coolmax midweight hiking crew socks- $13.95 Fox River Adventure cross terrain 2 pack- $19.95 Available at Sportsman’s Warehouse: Fox River boot and field thermal socks $7.99 Fox River work thermal 2 pack- $15.99 Available at Army/Navy Surplus: Fox River hike, trek, and trail- $8.99 Available at Army/Navy Surplus Outlet: Fox River work steel toe crew 6 pack- $20 Long Underwear 1 set, top & bottom. Midweight, heavyweight, or "expedition weight”. Base layers should be synthetic, silk, or wool. Look for new anti-microbial fabrics that don't get stinky. No cotton. Available at Wal-Mart: Women’s Climate Right by CuddlDuds long sleeve crew and leggings- $9.96 each Men’s Russel base layers top and bottom- $12.72 each Available at Sportsman’s Warehouse: Coldpruf enthusiast base layer top and bottom- $17.99 each Sweater Heavy fleece, synthetic, thin puffy, or wool. -

Notes 1. This Chapter Applies Only to Made-Up Knitted

Section XI - Chapter 61 Articles of Apparel and Clothing Accessories, Knitted or Crocheted Notes 1. This chapter applies only to made-up knitted or crocheted articles. 2. This chapter does not cover: (a). Goods of heading 6212; (b). Worn clothing or other worn articles of heading 6309; (c). Orthopedic appliances, surgical belts, trusses or the like (heading 9021). 3. For the purposes of headings 6103 and 6104: (a). The term "suit" means a set of garments composed of two or three pieces made up, in respect of their outer surfaces, in identical fabric and comprising: - one suit coat or jacket the outer shell of which, exclusive of sleeves, consists of four or more panels, designed to cover the upper part of the body, possibly with a tailored waistcoat in addition whose front is made from the same fabric as the outer surface of the other components of the set and whose back is made from the same fabric as the lining of the suit coat or jacket; and - one garment designed to cover the lower part of the body and consisting of trousers, breeches or shorts (other than swimwear), a skirt or a divided skirt, having neither braces nor bibs. All of the components of a "suit" must be of identical fabric construction, color and composition; they must also be of the same style and of corresponding or compatible size. However, these components may have piping (a strip of fabric sewn into the seam) in a different fabric. If several separate components to cover the lower part of the body are presented together (for example, two pairs of trousers or trousers and shorts, or a skirt or divided skirt and trousers), the constituent lower part shall be one pair of trousers or, in the case of women's or girls' suits, the skirt or divided skirt, the other garments being considered separately. -

Requirements and the Supreme Court Changes Citation Formats

Illinois Association of Defense Trial Counsel Springfield, Illinois | www.iadtc.org | 800-232-0169 IDC Quarterly | Volume 21, Number 3 (21.3.32) Appellate Practice Corner By: Brad A. Elward Heyl, Royster, Voelker & Allen, P.C., Peoria The First District Revisits Rule 304(a) Requirements and the Supreme Court Changes Citation Formats While decisions reporting on appellate issues seem to be rare, we have one for this issue. In Palmolive Tower Condominiums, LLC v. Simon, the appellate court dismissed a party’s appeal for want of a final and appealable order, specifically finding that the circuit court’s statement, “[t]his order is final and appealable,” was incomplete and, therefore, failed to confer appellate jurisdiction under Rule 304(a). Rule 304(a) says, in part: If multiple parties or multiple claims for relief are involved in an action, an appeal may be taken from a final judgment as to one or more but fewer than all of the parties or claims only if the trial court has made an express written finding that there is no just reason for delaying either enforcement or appeal or both. Such a finding may be made at the time of the entry of the judgment or thereafter on the court’s own motion or on motion of any party. … In the absence of such a finding, any judgment that adjudicates fewer than all the claims or the rights and liabilities of fewer than all the parties is not enforceable or appealable and is subject to revision at any time before the entry of a judgment adjudicating all the claims, rights, and liabilities of all the parties. -

Research Guide

Research Guide FINDING CASES I. HOW TO FIND A CASE WHEN YOU KNOW THE CITATION A. DECIPHERING LEGAL CITATIONS 1. CASE CITATIONS A case citation includes: the names of the parties, the volume number of the case reporter, the abbreviated name of the reporter, the page number where the case can be found, and the year of the decision. EXAMPLE: Reserve Insurance Co. v. Pisciotta, 30 Cal.3d 800 (1982). Reserve Insurance Co. v. Pisciotta = names of the parties 30 = volume number of the case reporter Cal. = abbreviated name of the case reporter, California Reports 3d = series number of the case reporter, California Reports 800 = page number of the case reporter (1982) = year of the decision 2. ABBREVIATIONS OF REPORTER NAMES The abbreviations used in citations can be deciphered by consulting: a. Prince’s Bieber Dictionary of Legal Abbreviations, 6th ed. (Ref. KF 246 .p74 2009) b. Black's Law Dictionary (Ref. KF 156 .B624 2009). This legal dictionary contains a table of abbreviations. Copies of Black's are located on dictionary stands throughout the library, as well as in the Reference Collection. 3. REPORTERS AND PARALLEL CITATIONS A case may be published in more than one reporter. Parallel citations indicate the different reporters publishing the same case. EXAMPLE: Reserve Insurance Co. v. Pisciotta, 30 Cal.3d 800, 180 Cal. Rptr. 628, 640 P.2d 764 (1982). 02/08/12 (Rev.) RG14 (OVER) This case will be found in three places: the "official" California Reports 3d (30 Cal. 3rd 800); and the two "unofficial" West reporters: the California Reporter (180 Cal.