Preference Erosion:After Hong Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

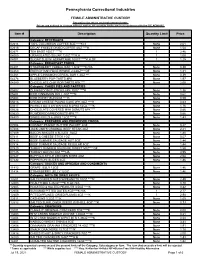

FEMALE ADMINISTRATIVE CUSTODY See Policy for Return and Replacement Terms

Pennsylvania Correctional Industries FEMALE ADMINISTRATIVE CUSTODY See policy for return and replacement terms. Prices are subject to change without notice. All quantity limits are in accordance with the DC ADM-815. Item # Description Quantity Limit Price Category: BEVERAGES 02614 100% COLUMBIAN COFFEE 5OZ ****K,H None 2.61 02616 DECAF FREEZE DRIED COFFEE 4OZ ****K None 1.54 02671 TEA BAGS 100CT ****K 1 2.46 04000 GRANULATED SUGAR 12OZ ****K,H 1 1.00 04001 SUGAR SUB W/ ASPARTAME 100CT ****K,H,GF 1 1.25 Category: BREAKFAST FOODS 04201 STRAWBERRY CEREAL BAR 1.3OZ ****K,H/A None 0.39 04260 ENERGY BAR,FDGE BRWNE 2.64OZ****GF None 1.31 04261 APPLE CINNAMON CEREAL BAR 1.3OZ *** None 0.39 04276 BLUEBERRY POP-TARTS 8PK None 1.97 04280 CHOCOLATE CHIP POP-TARTS 8PK *** None 2.00 Category: CAKES PIES AND PASTRIES 05602 DUNKIN DONUT STICKS 6PK 10OZ ****K None 1.36 05604 ICED CINNAMON ROLL 4OZ ****K None 0.62 05608 ICED HONEY BUN 6OZ ****K None 0.59 05616 CREAM CHEESE POUND CAKE 2PK 4OZ ****K None 0.63 05617 PEANUT BUTTER WAFERS 6-2PKS 12OZ ****K None 1.76 05628 CHOCOLATE COVERED MINI DONUTS 6PK *** None 0.66 05630 POWDERED MINI DONUTS 6PK *** None 0.66 06800 SWISS ROLLS 6-2PKS 12OZ ****K None 1.43 Category: PREPARED AND PRESERVED FOODS 07004 CREAMY PEANUT BUTTER PACKET 2OZ None 0.27 07406 JACK LINK'S ORIGINAL BEEF STEAK 2OZ None 2.21 07409 BACON SINGLES 6 SLICES .78OZ None 1.80 07411 BEEF & CHEESE STICK 1OZ None 0.57 07413 BEEF SUMMER SAUSAGE HOT 5OZ None 1.44 07414 BEEF SUMMER SAUSAGE REGULAR 5OZ None 1.44 07420 TURKEY SUMMER SAUSAGE SWEET 5OZ****GF -

Boxers Or Briefs Poll

Boxers Or Briefs Poll Fun Poll, Boxers or Briefs? Cast your vote and then share with your friends to get their vote. Welcome to Zity. 15%: Plain nondescript underwear. I personally prefer boxers, but they get so annoying. For women the options were briefs, bikini, shorts and thongs. Pants for sport, boxers otherwise. Seems it's a big deal with some of the younger crowd out there, (under 40) that says it's a big deal if you wear whitey tightys, boxers of briefs. 57% (647) Boxer briefs. Sam Talbot (Top Chef) - "boxers, briefs and commando" Rob Thomas (lead singer of Matchbox Twenty) Justin Timberlake (pop musician and actor) - started in briefs; switched to boxers; then to boxer briefs and sometimes commando; about boxer briefs, his current preference, he says: "like the way they hold everything together". 10 Answers. The new findings from the National Poll on Healthy Aging suggest that more physicians should routinely ask their older female patients about incontinence issues they might be experiencing. Tighty Whiteys are NOT cool (not saying you show your underwear to everyone). Share Followers 0. They also offer refastenable hook tabs and curved leg elastics like adult diapers for a fit that stays in place and helps you, or those you love, stay confident and comfortable. This comment has been removed by the author. Here's how to debrief his briefs. Kagura = 878 8. Boxers, Briefs and Battles. I in uncomplicated words switched to briefs/boxers, which ability i have were given lengthy lengthy previous from in uncomplicated words boxers to many times situations boxers, on get jointly briefs. -

Mariejo-SWIM-2022Vk.Pdf

SWIM COLLECTION SS22 SWIM MARIE JO SWIM COLLECTION The fashion collection 5 Styles overview Marie Jo 6 NEW FASHION PIECES Murcia 8 Sitges 10 Tarifa 12 Terrassa 14 Zaragoza 16 Julia 18 Camila 20 Cadiz 22 Cordoba 24 Pamplona 26 Valentina 28 Labels & patents 30 SITGES SWIMSUIT 1004630 POOLSIDE ELEGANCE BEACH FUN Stylish, more timeless looks Playful looks and styles Create an elegant silhouette Latest trends & colors SITGES MLC MURCIA YFS Seasonal CORDOBA RNF TARIFA TBS Marie Jo Swim Fashion collection PAMPLONA FRE ZARAGOSA PUN CADIZ WBL TERRASSA PPZ VALENTINA EVB JULIA ARB CAMILA RNB Spring/Summer 2022 | © Copyright NV Van de Velde STYLES OVERVIEW MARIE JO SWIM SS22 BIKINI TOPS SWIMSUIT BOTTOMS ACCESSORIES TOP TRIANGLE FULL CUP HEART SHAPE DEEP PLUNGE PUSH-UP STRAPLESS BALCONY TRIANGLE PADDED NON PADDED PADDED RIO BRIEFS FULL BRIEFS FOLD BRIEFS WAIST ROPES WIRE PADDED PADDED PADDED PADDED PADDED PADDED PUSH-UP MURCIA BEACH FUN BEACH SITGES POOLSIDE POOLSIDE ELEGANCE TARIFA BEACH FUN BEACH TERRASSA BEACH FUN BEACH ZARAGOZA BEACH FUN BEACH JULIA BEACH FUN BEACH CAMILA BEACH FUN BEACH CADIZ POOLSIDE POOLSIDE ELEGANCE CORDOBA POOLSIDE POOLSIDE ELEGANCE PAMPLONA POOLSIDE POOLSIDE ELEGANCE VALENTINA POOLSIDE POOLSIDE ELEGANCE PADDED CUPS HALTER NECK REMOVABLE STRAPS WIRELESS Spring/Summer 2022 | © Copyright NV Van de Velde RECYCLED MATERIALS Yellow Flash - YFS MURCIA 1005114 1005116 1005119 bikini triangle padded push-up bikini top heart shape padded bikini top balcony padded EUR: XS-L EUR: A 70-85 / B-D 70-90 / E 70-85 / F 70-80 EUR: B 70-90 / C-D 65-90 / E 65-85 FR: XS-L FR: A 85-100 / B-D 85-105 / E 85-100 / F 85-95 FR: B 85-105 / C-D 80-105 / E 80-100 UK: XS-L UK: A 32-38 / B-D 32-40 / E 32-38 / F 32-36 UK: B 32-40 / C-D 30-40 / E 30-38 ..................................... -

Winter Hut Trip Packing List

Red Rock Recovery Center Experiential Program Packing List Winter Winter Boots Insulated, waterproof, and above the ankle. Available at Wal-Mart: Men’s Ozark Trail winter boots- $29.84 Men’s winter boots (grey moon boots)- $19.68 Women’s Ozark Trail winter boots- $46.86 Available at REI: Women’s and men’s Sorel Caribou boots- $150 Men’s Kamik William snow boot- $149.95 Men’s North Face Chilkat- $150 Available at Sportsman’s Warehouse: Women’s Northside Kathmandu boots- $74.99 Women’s Northside Bishop Boots- $54.99 Women’s Kamik Momentum- $84.99 Men’s Kamik Nation Plus boots- $79.99 Socks 2 heavy weight wool. No cotton. Available at Wal-Mart: Men’s Kodiak wool socks (2 pack)- $9.48 Men’s Dickies crew work socks- $8.77 Available at REI: REI Coolmax midweight hiking crew socks- $13.95 Fox River Adventure cross terrain 2 pack- $19.95 Available at Sportsman’s Warehouse: Fox River boot and field thermal socks $7.99 Fox River work thermal 2 pack- $15.99 Available at Army/Navy Surplus: Fox River hike, trek, and trail- $8.99 Available at Army/Navy Surplus Outlet: Fox River work steel toe crew 6 pack- $20 Long Underwear 1 set, top & bottom. Midweight, heavyweight, or "expedition weight”. Base layers should be synthetic, silk, or wool. Look for new anti-microbial fabrics that don't get stinky. No cotton. Available at Wal-Mart: Women’s Climate Right by CuddlDuds long sleeve crew and leggings- $9.96 each Men’s Russel base layers top and bottom- $12.72 each Available at Sportsman’s Warehouse: Coldpruf enthusiast base layer top and bottom- $17.99 each Sweater Heavy fleece, synthetic, thin puffy, or wool. -

Notes 1. This Chapter Applies Only to Made-Up Knitted

Section XI - Chapter 61 Articles of Apparel and Clothing Accessories, Knitted or Crocheted Notes 1. This chapter applies only to made-up knitted or crocheted articles. 2. This chapter does not cover: (a). Goods of heading 6212; (b). Worn clothing or other worn articles of heading 6309; (c). Orthopedic appliances, surgical belts, trusses or the like (heading 9021). 3. For the purposes of headings 6103 and 6104: (a). The term "suit" means a set of garments composed of two or three pieces made up, in respect of their outer surfaces, in identical fabric and comprising: - one suit coat or jacket the outer shell of which, exclusive of sleeves, consists of four or more panels, designed to cover the upper part of the body, possibly with a tailored waistcoat in addition whose front is made from the same fabric as the outer surface of the other components of the set and whose back is made from the same fabric as the lining of the suit coat or jacket; and - one garment designed to cover the lower part of the body and consisting of trousers, breeches or shorts (other than swimwear), a skirt or a divided skirt, having neither braces nor bibs. All of the components of a "suit" must be of identical fabric construction, color and composition; they must also be of the same style and of corresponding or compatible size. However, these components may have piping (a strip of fabric sewn into the seam) in a different fabric. If several separate components to cover the lower part of the body are presented together (for example, two pairs of trousers or trousers and shorts, or a skirt or divided skirt and trousers), the constituent lower part shall be one pair of trousers or, in the case of women's or girls' suits, the skirt or divided skirt, the other garments being considered separately. -

Appendix List of Controlled Items Subject to New Quantity Limitation

Appendix List of controlled items subject to new quantity limitation: Ready-Made Clothes HS Code Heading Description 6101 Men's or boys' overcoats, car-coats, capes, cloaks, wind-jackets & similar articles, knitted or crocheted 6102 Women's or girls' overcoats, car-coats, capes, cloaks, wind- jackets & similar articles, knitted or crocheted 6103 Men's or boys' suits, ensembles, jackets, blazers, trousers, bib and brace overalls, breeches & shorts, knitted or crocheted 6104 Women's or girls' suits, ensembles, trousers, bib & brace overalls, breeches & shorts, etc, knitted or crocheted 6105 Men's or boys' shirts, knitted or crocheted 6106 Women's or girls' blouses, shirts and shirt-blouses, knitted or crocheted 6107 Men's or boys' underpants, briefs, nightshirts, pyjamas, bathrobes, dressing gowns and similar articles, knitted or crocheted 6108 Women's or girls' slips, briefs, panties, nightdresses, bathrobes & similar articles, knitted or crocheted 6109 T-shirts, singlets and other vests, knitted or crocheted 6110 Jerseys, pullovers, cardigans, waistcoats and similar articles, knitted or crocheted 6111 Babies' garments and clothing accessories, knitted or crocheted 6112 Track suits, ski suits and swimwear, knitted or crocheted 6113 Garments, made up of knitted or crocheted fabrics of heading No.59.03, 59.06 or 59.07 6114 Other garments, knitted or crocheted 6115 Panty hose, tights, stockings, socks & other hosiery, knitted or crocheted 6116 Gloves, mittens and mitts, knitted or crocheted 6117 Other made up clothing accessories, knitted -

Research Brief: Student Dress Codes and Uniforms

Research Brief Student Dress Codes and Uniforms Question(s): What are the issues surrounding dress codes for secondary students? How can schools create appropriate dress code policies? In A Nutshell According to an Education Commission of the States Policy Report, research on the effects of dress code and school uniform policies is inconclusive and mixed. Some researchers find positive effects; others claim no effects or only perceived effects. While no state has legislatively mandated the wearing of school uniforms, 28 states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws addressing school attire. (ERIC Clearinghouse on Educational Management, Fall 2002). Recent challenges have focused on the chilling effect that dress codes have on free speech (e.g., the expression or religious or political ideas) or the burdens that new dress requirements, particularly uniforms, place on poor parents who cannot afford to bring their children into compliance. Also, some parents and legal authorities claim that when students either are sent home or placed in isolation because of dress code violations, it has a negative effect on their educational opportunity and ultimate performance. Long after President Clinton called for the use of uniforms to help reduce school violence in 1996, the debate over the effectiveness and constitutionality of school dress codes, while muted in recent years, continues. Legal Issues While dress is broadly protected as a form of free speech under the first amendment of the Constitution, the courts have recognized the special role of schools in American life and the unique needs of the school environment. As a result, most states have laws that permit schools to regulate student dress as long as the purposes of doing so are clearly connected to student safety and the maintenance of an orderly school environment. -

2010 ANNUAL Reportpage 1

2010N AN UAL REPORT 0526_cov.indd 2 4/7/11 10:30 AM COMPARISON OF 5 YEAR CUMULATIVE TOTAL RETURN* Among The Warnaco Group, Inc., the Russell 2000 index, the S&P Midcap 400 index, the Dow Jones US Clothing & Accessories index $250 and the S&P Apparel, Accessories & Luxury Goods index COMPARISONCOMParisON OF OF 5YEAR 5-YEar CCUMULATIVEUMULatiVE TO TOTALtaL RE TRETURN*Urn* e Warnaco Group, Inc. compared to select indices $250 $200 250 250 $200 $150 200 200 $150 150 150 $100 $100 100 100 $50 $50 50 50 $0 0 0 $0 3/06 6/06 9/06 3/07 6/07 9/07 3/08 6/08 9/08 3/09 6/09 9/09 3/10 6/10 9/10 12/05 12/06 12/07 12/08 12/09 12/10 12/05 3/06 6/06 9/06 12/06 3/07 6/07 9/07 12/07 3/08 6/08 9/08 12/083/096/09 9/09 12/09 3/10 6/10 9/10 12/10 e Warnaco Group, Inc. Russell 2000 S&P MidCap 400 Dow Jones U.S. Clothing & Accessories The Warnaco Group, Inc. Russell 2000 S&P Apparel, Accessories & Luxury Goods *$100 invested on 12/31/05 in stock or index, including reinvestment of dividends. Fiscal year ending December 31. S&P Midcap 400 Dow Jones US Clothing & Accessories Copyright © 2011 S&P, a division of e McGraw-Hill Companies Inc. All rights reserved. Copyright © 2011 Dow Jones & Co. All rights reserved. S&P Apparel, Accessories & Luxury Goods *$100 invested on 12/31/05 in stock or index, including reinvestment of dividends. -

Handbook on Briefs and Oral Arguments

HANDBOOK ON BRIEFS AND ORAL ARGUMENTS by THE HON. ROBERT E. DAVISON and DAVID P. BERGSCHNEIDER ©2007 by the Office of the State Appellate Defender. All rights reserved. Updated 2020 by: Kerry Bryson & Shawn O’Toole, Deputy State Appellate Defenders State Appellate Defender Offices Administrative Office Third District Office 400 West Monroe - Suite 202 770 E. Etna Road Springfield, Illinois 62705 Ottawa, Illinois 61350 Phone: (217) 782-7203 Phone: (815) 434-5531 Fax: (217) 782-5385 Fax: (815) 434-2920 First District Office Fourth District Office 203 N. LaSalle, 24th Floor 400 West Monroe - Suite 303 Chicago, Illinois 60601 Springfield, Illinois 62705-5240 Phone: (312) 814-5472 Phone: (217) 782-3654 Fax: (312) 814-1447 Fax: (217) 524-2472 Second District Office Fifth District Office One Douglas Avenue, 2nd Floor 909 Water Tower Circle Elgin, Illinois 60120 Mount Vernon, Illinois 62864 Phone: (847) 695-8822 Phone: (618) 244-3466 Fax: (847) 695-8959 Fax: (618) 244-8471 Juvenile Defender Resource Center 400 West Monroe, Suite 202 Springfield, Illinois 62704 Phone: (217) 558-4606 Email: [email protected] i INTRODUCTION The first edition of this Handbook was written in the early 1970's by Kenneth L. Gillis, who went on to become a Circuit Court Judge in Cook County. The Handbook was later expanded by Robert E. Davison, former First Assistant Appellate Defender and Circuit Court Judge in Christian County. Although the Handbook has been updated on several occasions, the contributions of Judges Gillis and Davison remain an essential part. The lawyers who use this Handbook are encouraged to offer suggestions for improving future editions. -

Boxers Or Briefs? Neither

Boxers Or Briefs? Neither. It’s Trunks. By Deborah Weinswig for Forbes August 15, 2016 We recently teamed up Gen X: “Boxers Or Millennials: Defined By with First Insight, which Briefs?” Leads To “The The Trunk offers companies a platform Boxer Brief” for consumer testing of products, to analyze According to First Insight consumer tests of men’s In 1994, a high school data, prices of men’s trunk apparel conducted since student at an MTV - underwear have risen by 2013. The findings show sponsored town hall 44% over the past three that, although men’s apparel famously asked Bill Clinton, years, and the volume of prices overall have fallen by “Is it boxers or briefs?” He trunks tested via the 27.8% over the period, laughed and answered, company’s platform has men’s underwear prices “Usually briefs.” The fact boosted tests in the entire have, in fact, increased by that he answered at all men’s underwear category 34%. We also found that the endeared him to Gen Xers. by 34% over the same number of tests conducted on Around the same time, John period. In 2013, trunks men’s accessories via First Varvatos cut off a pair of accounted for just 8% of the Insight has grown by 681% long johns and called them total men’s underwear tests over the past three years. “boxer briefs.” Now, conducted via First Insight’s The popular BPOP according to data from The platform; in 2016 to date, +0.70% sock category, NPD Group, boxer briefs are they have represented 56% where the number of tests the dominant form of men’s of the total. -

Case 2:04-Cr-00688-CW Document 263 Filed 07/21/08 Page 1 of 9

Case 2:04-cr-00688-CW Document 263 Filed 07/21/08 Page 1 of 9 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF UTAH UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, MEMORANDUM DECISION AND Plaintiff, REPORT & RECOMMENDATION vs. Case No: 2:04-CR-688 DB JAMES FRED GORDON and DANELLE DECEW, District Judge Dee Benson Defendants. Magistrate Judge David Nuffer Defendant James Fred Gordon filed two motions to suppress evidence seized during a 1 search of his person at the time of his arrest on October 1, 2004. After an evidentiary hearing, 2 the magistrate judge concludes that because the search was reasonable under the Fourth Amendment, the motions should be denied. FACTS On September 30, 2004, Officer Michael Ikemiyashiro of the Sandy City police received a phone call from West Jordan Police Detective Lance Swanson. The detective informed Officer Ikemiyashiro that he had learned from a confidential source that Defendant Gordon was staying at a hotel in Sandy City. The confidential source stated that Gordon was a member of the Silent 1Docket no. 228, filed March 20, 2008; docket no. 258, filed June 17, 2008. The second motion to suppress is actually a memorandum in support of the first motion to suppress. It was docketed as a motion to suppress because its caption labels it as a motion, rather than a supporting memorandum. 2The case was referred to the magistrate judge under 28 U.S.C. § 636(b)(1)(B). (Docket no. 237, filed April 15, 2008.) Case 2:04-cr-00688-CW Document 263 Filed 07/21/08 Page 2 of 9 Aryan Warriors, a prison gang, and was known to carry firearms. -

A Study of Fashion Change Related to Men's Boxer Undershorts As Depicted in Sears Annual Merchandise Catalogs 1946-1988

AN ABSTRACT OF THESIS OF Bernadette A. Tatarka for the degree of Master of Science in Apparel, Interiors, and Merchandising presented on May 22, 1990. Title: A Study of Fashion Changes Related To Men's Boxer Undershorts As Depicted In Sears Annual Merchandise Catalogs (1946-1988) Abstract approved_Redacted for Privacy More research has been conducted regarding women's costume history than that of men's historic costume. One area in which little research has been conducted concerns men's boxer underwear. The need for additional research dealing with basic style changes of men's boxer undershorts was compelling to this researcher, as well as adding to the literature concerning men's historic costume. The purpose of this study was to research the availability of men's boxer undershorts post World War II (1946-1988). Specifically, based on pictorial underwear fashions illustrated in the Sears Annual Merchandise Catalog, this study documented and analyzed the availability of boxer undershorts as to fiber content, fabric structure, color, style features, and special design motifs during the time period studied. The objective of the study was to increase the knowledge of men's historic costume through an investigation into the styles of men's boxer undershorts. The historical continuity of fashion, as well as other theories concerning fashion change served as the theoretical framework for this study. The historical continuity process of fashion proposes that each new fashion is an evolutionary outgrowth and elaboration of the previous fashion (Blumer, 1969). Examples include past research by Young (1937), Kroeber (1919), and Robinson (1976), which indicated that changes in fashions took place in well-defined cycles.