Towards an Effective Class Action Model for European Consumers: Lessons Learnt from Israel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

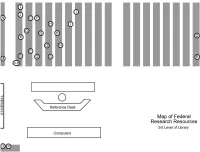

Fedresourcestutorial.Pdf

Guide to Federal Research Resources at Westminster Law Library (WLL) Revised 08/31/2011 A. United States Code – Level 3 KF62 2000.A2: The United States Code (USC) is the official compilation of federal statutes published by the Government Printing Office. It is arranged by subject into fifty chapters, or titles. The USC is republished every six years and includes yearly updates (separately bound supplements). It is the preferred resource for citing statutes in court documents and law review articles. Each statute entry is followed by its legislative history, including when it was enacted and amended. In addition to the tables of contents and chapters at the front of each volume, use the General Indexes and the Tables volumes that follow Title 50 to locate statutes on a particular topic. Relevant libguide: Federal Statutes. • Click and review Publication of Federal Statutes, Finding Statutes, and Updating Statutory Research tabs. B. United States Code Annotated - Level 3 KF62.5 .W45: Like the USC, West’s United States Code Annotated (USCA) is a compilation of federal statutes. It also includes indexes and table volumes at the end of the set to assist navigation. The USCA is updated more frequently than the USC, with smaller, integrated supplement volumes and, most importantly, pocket parts at the back of each book. Always check the pocket part for updates. The USCA is useful for research because the annotations include historical notes and cross-references to cases, regulations, law reviews and other secondary sources. LexisNexis has a similar set of annotated statutes titled “United States Code Service” (USCS), which Westminster Law Library does not own in print. -

Current Sources for Federal Court Decisions Prepared by Frank G

Current Sources for Federal Court Decisions Prepared by Frank G. Houdek, January 2009 Level of Court Name of Court Print Source Westlaw* LexisNexis* Internet TRIAL District Court Federal Supplement, 1932 •Dist. Court Cases—after •US Dist. Court Cases, U.S. Court Links (can select (e.g., S.D. Ill.) to date (F. Supp., F. 1944 Combined by type of court & Supp. 2d) •Dist. Court Cases—by •Dist. Court Cases—by location) circuit circuit http://www.uscourts.gov •Dist Court Cases—by •Dist. Court Cases—by state /courtlinks/ state/territory Federal Rules Decisions, 1938 to date (F.R.D.) Bankruptcy Court Bankruptcy Reporter, •Bankruptcy Cases—by US Bankruptcy Court Cases U.S. Court Links (can select 1979 to date (B.R.) circuit by type of court & location) •Bankruptcy Courts http://www.uscourts.gov /courtlinks/ INTERMEDIATE Courts of Appeals (e.g., Federal Reporter, 1891 to •US Courts of Appeals •US Courts of Appeals U.S. Court Links (can select APPELLATE 7th Cir., D.C. Cir.) date (F., F.2d, F.3d) Cases Cases, Combined by type of court & location) [formerly Circuit •Courts of Appeals •Circuit Court Cases—by http://www.uscourts.gov Courts of Appeals] Cases—by circuit circuit /courtlinks/ Federal Appendix, 2001 to US Courts of Appeals date (F. App’x) Cases, Unreported HIGHEST Supreme Court •United States Reports, All US Supreme Court US Supreme Court Cases, •Supreme Court of the APPELLATE 1790 to date (U.S.) Cases Lawyers’ Edition United States, •Supreme Court Reporter, 1991–present, 1882 to date (S. Ct.) http://www.supremecour •United States Supreme tus.gov/opinions/opinion Court Reports, s.html Lawyers’ Edition, 1790 •HeinOnline, vol. -

Federal Criminal Defense Practice Seminar

at 3524. g ysda.or Federal Criminal Defense Practice ! Seminar Cancellations: Registered participants who are unable to attend the program, PLEASE notify Diane DuBois at ddubois@n NYSDA to reduce program costs and expenses. NYSDA Thank you Sponsored by the Office of the Federal Public Defender for the Northern District of New York and the New York State sda.org y Defenders Association to: Tuesday, MCLE Skills Credits November 7, 2017 NYSDA has been certified by the New York Email: ddubois@n 8:00 am-3:50 pm State Continuing Legal Education Board as an Accredited Provider of continuing legal edu- cation in the State of New York (2016-2019). Foley Federal Courthouse This transitional/nontransitional program has 445 Broadway, 4th Fl Courtroom been approved in accordance with the requirements of the Continuing Legal Edu- Albany, NY 12207 cation Board for a maximum of 6.0 credit (New Location) hours. No CLE credit may be earned for New York State Defenders Association York New Suite 500 Ave., Washington 194 NY 12210-2314 Albany, Fax: 518-465-3249 Tuesday, October 31, 2017 October 31, Tuesday, repeat attendance at any accredited CLE Registration Form: Federal Criminal Defense Practice Seminar — November 7, 2017 7, Criminal Defense Practice Seminar — November Federal Registration Form: 6.0 MCLE Skills Credits This seminar is intendedThis for ALL practicing Criminal Defense Counsel. Questions? Please call Federal 518-465- You MUST completeYou this form and return it by THERE IS NO FEE FOR THIS SEMINAR. PRE-REGISTRATION IS REQUIRED. Name:________________________________________________________ Office: ______________________________________________ Address: ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ City/State/Zip:_________________________________________________ Email:_______________________________________________ Telephone: ___________________________________________________ FAX: ________________________________________________ activity within any one reporting cycle. -

ALWD Federal Citation Formats

ALWD Federal Citation Formats Below are examples of the Association of Legal Writing Directors (ALWD) style citations most commonly used by students at the College of DuPage. For additional examples and rules, please consult the ALWD Citation Manual. ALWD & Darby Dickerson, ALWD Citation Manual (4th ed., Aspen Publisher 2010). The below citation examples have been compiled by Lorri Scott, J.D., Maria Mack, J.D., and Linda Jenkins, J.D., from the C.O.D. Paralegal Studies Program. They were updated by Linda Jenkins, J.D. and Anne Knight, J.D., in December 2012. ALWD Federal Citations General Rules • Follow General Abbreviations (ALWD Appendix 3) when listing countries, states, cities, districts, dates, etc. • Case names are italicized (Tex. v. Johnson) or underlined (Tex. v. Johnson). (ALWD 1.1) • Do not italicize or underline the comma after the case name. (ALWD 1.4) • Abbreviate versus to "v." • Place a period after every citation. All citations are complete sentences. United States Supreme Court [Case name], [official reporter volume number] [official reporter abbreviation] [initial page number] (Date). Tex. v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989). • ALWD 12.4 (c) states one should cite only the official reporter, unless it is unavailable. • Note: ALWD 12.2(h)(2) states it is optional to abbreviate the state name. The case could also be cited Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989). • Bluebook requires the full state name. Tip: The Bluebook citation is Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989). Follow the format favored by your boss or by the judge for whom you are preparing documents. -

Precedent and the Role of Unpublished Decisions

The Journal of Appellate Practice and Process Volume 3 Issue 1 Article 19 2001 Are Some Words Better Left Unpublished?: Precedent and the Role of Unpublished Decisions K.K. DuVivier Follow this and additional works at: https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/appellatepracticeprocess Part of the Common Law Commons, and the Courts Commons Recommended Citation K.K. DuVivier, Are Some Words Better Left Unpublished?: Precedent and the Role of Unpublished Decisions, 3 J. APP. PRAC. & PROCESS 397 (2001). Available at: https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/appellatepracticeprocess/vol3/iss1/19 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Journal of Appellate Practice and Process by an authorized administrator of Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARE SOME WORDS BETTER LEFT UNPUBLISHED?: PRECEDENT AND THE ROLE OF UNPUBLISHED DECISIONS K.K. DuVivier* INTRODUCTION In the summer of 2000, a three-judge panel of the Eighth Circuit issued a decision that, if followed nationwide, could cripple our court system. In that decision, Anastasoff v. United States,' the Eighth Circuit determined that the portion of its Rule 28A(i) providing that unpublished opinions could be cited but were not binding as precedent, was unconstitutional. The selective designation of some opinions as unpublished is a fairly recent phenomenon for courts.' However, in the two * Copyright © 2001 by K.K. DuVivier. Ms. DuVivier is an Assistant Professor and Director of the Lawyering Process Program at the University of Denver College of Law. She has been chair and vice-chair of the Colorado Bar Association's Appellate Practice Subcommittee since 1996, and she has served as the Reporter of Decisions for the Colorado Court of Appeals. -

2.50 MB SEP 2 2020 Useful Points of Federal

USEFUL POINTS OF FEDERAL LAW Introduction In 1976 I began collecting on 3x5 cards what I=ve labeled, here, as Auseful points of law@ - one card per point. Eventually I gave up the cards in favor of the computer. When I became the Federal Public Defender in late 1998, I started collecting federal cases. What follows is that collection I began in 1998. I=ve put it on line in hopes the information will be of value to the members of our North Florida panel and the lawyers within our office. The majority of the Apoints@ come from the 11th Circuit and the United States Supreme Court. There are, though, some from other jurisdictions as I sometimes include them when I run across a decision I think is helpful. What I=ve included represents points of law that I think I might be able to use to defend a client, that address an issue that I need to know, or that states an established principle for which I might someday need a citation. Please know that this document is no longer up to date. The last couple of years I just haven’t had time to keep it up. Still, I continue to use it as a starting point and the vast majority of caselaw remains valid. Be forewarned, too, there is no guarantee as to accuracy. I=m sure there are errors in the spelling of some of the case names and in the citations. Then, too, there isn=t any warranty as to the content of the summary. -

How to Locate a Case Using a Digest

Sacramento County Public Law Library 609 9th St. Sacramento, CA 95814 saclaw.org (916) 874-6012 >> Home >> Law 101 DIGESTS How to Locate a Case Using a Digest The Law Library has two sets of West Digests in print format (now published by Thomson Reuters): Table of Contents The United States Supreme Court Digest, used to locate 1. How to Locate a Case Using United States Supreme Court cases, is located in Compact Topic and Key Number System in Shelving next to the Supreme Court Reporter, at KF 101 .1 Westlaw ...................................... 2 U55. Like all digests, each volume in the set is updated 2. Abbreviations and Locations of with pocket parts. Case Reporters ............................ 4 West’s California Digest, located in Row C-9 of Compact Shelving at KFC 57 .W47, is used to locate California Supreme Court and California Appellate Court cases. Digests are arranged alphabetically by topic. Examples of the approximately 400 topics are: Banks and Banking, Franchises, Insurance, Libel and Slander, Partnership, Fraud, and Criminal Law. Each topic is divided into subtopics known as "key numbers." A complete list of topic headings is available in the front of each digest volume. A complete list of key numbers is available at the beginning of each topic. A Quick Reference Guide to West Key Number System is available online west.thomson.com/documentation/westlaw/wlawdoc/wlres/keynmb06.pdf. Locate a topic and key number that interests you by scanning the list of topic headings and key numbers or by using the Descriptive Word Index at the end of each set of digests. -

Recommended Collections, ;

•.> .... · . .. :' ~ -<··,(~ ._...... :. ; . .. ~ . :-·..:.:" -... - : - ·,~ .!.~:__ , A A L L ,;r: : • -. '.:: ·;:. - • • • • •.:. ReCommended Collections, ; FOR PRISON AND OTHER INSTITUTION LAW liBRARIES 1996__ r..e.yised ed. Includes Federal & State Recommended Collections Publisher Information I . .Prison Law Library Guidelines Deluxe Edition Contents Only Notebook, Dividers, Contents Contents $30.00 ~22.00 Shipping & Handling - $5~50 Shipping & Handling - $3.75 Total Price Deluxe Edition - $35.50 Total Price Contents Only- $25.75 .- Send prepaid orders to: ·. ·_.. :. ,~. Rebecca S. Trammell, University liege of Law - Schmid Law Libra ·r~:- ;::·:it;: Lineal 3 -0902 .>-~~·.· . (40 302 ~ • · .. .,: -' .. ' !' • .; . i . • American Associations of Law Libraries Social Responsibilities Special Interest Section Standing Committee on Law Library Service to Institution Residents RECOlVllvfENDED COLLECTIONS. FOR PRISON AND OTHER INSTITUTION LAW LIBRARIES & GUIDELINES FOR PRISON LAW LIBRARIES Edited by Rebecca S. Trammell, Chair Standing Committee on Law Library Service to Institution Residents. ..•. 1996 Table of Contents Introduction Federal Materials . • • . • . Part I General .Materials . Part II State Materials (arranged in alphabetical order by state) ........... .... .. Part Till Publisher Information . • . Part IV Prison Law Library Guidelines ........... ....... ... ...... Part V American Association of Law Libraries Social Responsibilities SIS Collection for Prison and Other Institution Law Libraries Federal Materials Note: Some materials listed here reference both state and federal issues. Such materials are listed once, in this section. Codes: United States Code Service. Constitution volumes; Title 18 and Federal Criminal Rules; Title 28 (sections 1961 -End) and Federal Rules of Evidence, Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure and Rules of the Supreme Court; Title 42 (2 volumes containing sections 1981 - 1985). l.a.wyer's Co-operative. 16 volumes. Approximately $28.00 per volume and an annual upkeep of approximately $5.00 per volume. -

William Taylor Muse Law Library University of Richmond School of Law

William Taylor Muse Law Library University of Richmond School of Law Research Guide : Federal Case Law Introduction Case law is the law as evidenced by a written judicial opinion. It is distinguished from statutory or administrative law although it frequently interprets these types of law. A judicial opinion is the expressed reasoning for the conclusion in a certain case. This research guide discusses how to locate federal case law. Although the focus here is on federal cases, the principles utilized to locate federal case law are applicable for locating the case law of a particular state. Basics Publication of opinions — Judicial opinions are published in three stages. The first is in the form of a slip opinion issued and published by the court soon after the decision is handed down. The second stage of publication is known as advance sheets, a portion of opinions that are ultimately published in the same reporter volume. Advance sheets typically contain the volume and page numbers of the future reporter volume. The final stage of publication is the actual reporter volume. The reporter contains several advance sheets bound into a new volume of the respective reporter series. Published v. Unpublished opinions — Not all cases result in judicial opinions that are published. Published opinions are available both online and in hard copy in one of the various series of reporters. — With regard to the federal courts of appeals, only those opinions deemed to have ―general precedential value‖ are designated for publication by the court. As of January 1, 2001, some unpublished opinions of the federal courts of appeals can be located in the Federal Appendix. -

Law Libraries Suggested Values for January 1, 2012

Law Libraries Suggested values for January 1, 2012 This schedule has been prepared by the Property Tax Division of the Department of Revenue, State of Oregon, in cooperation with the Oregon State Bar. Owners of Law Libraries should declare the schedule values to the assessor. No further reduction should be made for depreciation, shopwear, or obsolescence. Space prevents a listing of all books that might be found in a Law Library. The lack of a listing does not indicate that individual books, sets, or volumes should not be reported. Such unlisted books, sets, or volumes should be reported in Section Q values unless personal knowledge indicates greater actual value on some sets. Valuations and update cost figures based on best information available. Index Section Index Section Index Section Advanced Sheets and Pamphlets No Value Corpus Juris Secundum F Oregon Digest E American Bar Association Reports J Cumulative Bulletins (G.P.O.) N Oregon Law Review J American Decisions K Dictionaries D Oregon Reports N American Digest E Digest E Oregon Session Laws L American Jurisprudence F English Ruling Cases A Oregon Tax Court Reports N American Jurisprudence Legal Forms Rev. Ed. P Federal Cases N Other States’ CD T American Jurisprudence Pleading & Practice Rev. Ed. P Federal Digest E Pacific Digest E American Jurisprudence Trials P Federal Procedural Forms P Pacific Reporter H American Maritime Cases N Federal Reporter H Pacific States Reports N American Reports K Federal Rules Decisions H Periodicals & Law Journals J American State Reports K Federal -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 392 462 IR 055 848 TITLE Collection

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 392 462 IR 055 848 TITLE Collection Development Plan. INSTITUTION Minnesota State Law Library, St. Paul. PUB DATE 96 NOTE. 65p. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Interlibrary Loans; *Law Libraries; *Library Collection Development; Library Material Selection; *Library Planning; *Library Policy; Library Standards; Preservation IDENTIFIERS *Minnesota ABSTRACT This c.Alection development plan of the Minnesota State Law Library includes detailed information on policies and annotations. After an overview of the Library's collection, general policy guidelines on the following are discussed: material selection; principles of selection; exclusions; gifts; interlibrary loan; cooperation; replacements; duplication; electronic resources; preservation; weeding and storage; and standards. Policies on special collection areas are also identifi'ed. Annotations provide examinations and assessments of the Library's collection. In outline form, the following major areas are evaluated for what the Library should have and does have, as well as for other considerations: administrative decisiens and regulations; attorney general opinions; citators; constitutions; court reports and rules; dictionaries and encyclopedias; digests of case law; directories; form books; government documents; judicial administrative reports; legislative journals and studies; looseleaf services; newspapers; periodicals; practice manuals and procedural forms; session laws and statutes; standards; treaties; treatises and subject materials; and uniform laws and model acts. Appendices include the Minnesota State Law Library mission statelent, retention of titles in retired collections and storage, the American Association of Law Libraries Appellate Court 1..brary Standards, and the American Library Association Library Bill of Rights. (AEF) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

The Value of Unpublished Opinions and Their Effects on Precedent

Oklahoma Law Review Volume 59 Number 2 2006 Building Law, Not Libraries: The Value of Unpublished Opinions and Their Effects on Precedent Anika C. Stucky Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/olr Part of the Civil Procedure Commons Recommended Citation Anika C. Stucky, Building Law, Not Libraries: The Value of Unpublished Opinions and Their Effects on Precedent, 59 OKLA. L. REV. 403 (2006), https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/olr/vol59/iss2/5 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oklahoma Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Building Law, Not Libraries: The Value of Unpublished Opinions and Their Effects on Precedent* I. Introduction Over the past ten years, Americans have called on the federal and state judiciaries to settle an increasing number of disputes.1 Many factors contribute to the rise in case filings, but a rise in criminal appeals and immigration proceeding appeals in the wake of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks have demonstrably contributed to the increase.2 In response, courts have turned to the unpublished opinion as one method of managing the increased caseload. For example, in the twelve-month period ending September 30, 2005, the federal circuit courts filed 29,913 opinions in cases terminated on the merits.3 Of those opinions, 24,411 were unpublished, representing 81.6% of the total opinions filed.4 The United States Court of Appeals for the First * The author would like to thank Professor Mary Margaret Penrose for her assistance, advice, and encouragement throughout the author,s law school experience, especially during the writing of this comment.