UNBOUND an Annual Review of Legal History and Rare Books

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Understandings of the "Judicial Power" in Statutory Interpretation

ARTICLE ALL ABOUT WORDS: EARLY UNDERSTANDINGS OF THE 'JUDICIAL POWER" IN STATUTORY INTERPRETATION, 1776-1806 William N. Eskridge, Jr.* What understandingof the 'judicial Power" would the Founders and their immediate successors possess in regard to statutory interpretation? In this Article, ProfessorEskridge explores the background understandingof the judiciary's role in the interpretationof legislative texts, and answers earlier work by scholars like ProfessorJohn Manning who have suggested that the separation of powers adopted in the U.S. Constitution mandate an interpre- tive methodology similar to today's textualism. Reviewing sources such as English precedents, early state court practices, ratifying debates, and the Marshall Court's practices, Eskridge demonstrates that while early statutory interpretationbegan with the words of the text, it by no means confined its searchfor meaning to the plain text. He concludes that the early practices, especially the methodology ofJohn Marshall,provide a powerful model, not of an anticipatory textualism, but rather of a sophisticated methodology that knit together text, context, purpose, and democratic and constitutionalnorms in the service of carrying out the judiciary's constitutional role. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................... 991 I. Three Nontextualist Powers Assumed by English Judges, 1500-1800 ............................................... 998 A. The Ameliorative Power .............................. 999 B. Suppletive Power (and More on the Ameliorative Pow er) .............................................. 1003 C. Voidance Power ..................................... 1005 II. Statutory Interpretation During the Founding Period, 1776-1791 ............................................... 1009 * John A. Garver Professor ofJurisprudence, Yale Law School. I am indebted toJohn Manning for sharing his thoughts about the founding and consolidating periods; although we interpret the materials differently, I have learned a lot from his research and arguments. -

Caqe ,T-)65 61

eiF C714rd FF27JAIKL,ti Ckw.i,ZSI CAqE ,t-)65_61,. ;bo'7qra TAE C3h11© I-SuPRLrnE COi.I fF,a,qRh aF- CoFnmi SSiWER.SI 1N fvE: LE VEF2T K. PdE3221't2^. AKC^N.d^l ^f^r's^'L., t.^SES. A- LLCyt:LSTiN P. oSUEL^Sa7.ReGA(a.OGi 115% 511 M.MArN ST ./LMZc^ni.e^l1 4431U< .4AOa.... pE^,' 0 6 Z006 LAWREIJGE R. Sin^TiJ.FS©.,REG.NO.a©2902Es1 ONE CflSCA6E PLZ.. 7t1(.FL..AKR-dN.ON 44 3ej8, MARCIA J NIENGEL, CLERI( AEFTS.,APLEES..RES.... SUPREME CUF;! OF ILELATQiZ.AP('ELLAnfT, PLAu.ITiF'F LEVErc'l` K,C►RIPFrn! MOi IGaI FdR r-N7RY FdOR ALLEGE LdA1rQI.ITN6kI ZE P'cAcT 1 CE aF LAW L6t^^EN AGAwsT ZnTF1 A'T'f'oRAfEYs Lf1ldYER lA1LAPTlOAIEN As AL3ouE SEE NEraLE EXNIL3rT#'^"^4 "C° &IbuS CvMES,RELATafZ.ArPELLqM.PLAinitrFF LEUERT nc.6RIF'FiN.NE(mF3Y PRRY PbfZ RELIEF LLPOni'Ta WlliG.N RELIER CAnr BE GPtAn[TEd. A.rnaTrer.t FrafR Eti1TRY FoR ALLEGE dnrr4uTW0rtraE PreACTrcE aF LAru IoOisEO Afvr^,E6-ra ArTaRuEYs LAwyER. ^nsCA.PTranrE& AS AbevsE_ .SEC r(s,ucE cxAI PEr.li,rmL. L>APPE.FlL As QF R1a13T z^TRFanI Smi?R'Fa L eF RS.Car'.h LEVESZ~1 SOaw Cl-,..uSE- dRDE2 FOp^ REL)Ar11b, MmANf]E& TA)C f'fLEE AT ALL COS*P `TAlS RZEqmCLE5r wER Ciau F3AR rL, U rs 6lFl, PEnrtvAjG AISTddtC A7rVE REL/EF C,u P. RL. 55(a1^6) t*'s4,uERN WJLUE' 7)IE Au7'F1.. SctP CT RL. P"h.'00 , iti{E rgAl2cFoAln RL,$L.LIh^A^t^^JGR^ZEb PrZALT^CECK LAC^/. -

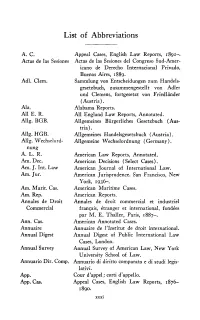

List of Abbreviations

List of Abbreviations A. C. Appeal Cases, English Law Reports, r8gr-. Aetas de las Sesiones Aetas de las Sesiones del Congreso Sud-Amer icano de Derecho Internacional Privado, Buenos Aires, r88g. Adl. Clem. Sammlung von Entscheidungen zum Handels gesetzbuch, zusammengestellt von Adler und Clemens, fortgesetzt von Friedlander (Austria). Ala. Alabama Reports. All E. R. All England Law Reports, Annotated. Allg. BGB. Allgemeines Biirgerliches Gesetzbuch (Aus- tria). Allg. HGB. Allgemeines Handelsgesetzbuch (Austria). All g. W echselord- Allgemeine Wechselordnung (Germany). nung A. L. R. American Law Reports, Annotated. Am. Dec. American Decisions ( Select Cases) . Am. J. Int. Law American Journal of International Law. Am. Jur. American Jurisprudence. San Francisco, New York, 1936-. Am. Marit. Cas. American Maritime Cases. Am. Rep. American Reports. Annales de Droit Annales de droit commercial et industriel Commercial fran~ais, etranger et international, fondees par M. E. Thaller, Paris, r887-. Ann. Cas. American Annotated Cases. Annuaire Annuaire de l'Institut de droit international. Annual Digest Annual Digest of Public International Law Cases, London. Annual Survey Annual Survey of American Law, New York University School of Law. Annuario Dir. Camp. Annuario di diritto comparato e di studi legis lativi. App. Cour d'appel; corti d'appello. App. Cas. Appeal Cases, English Law Reports, 1876- r8go. xxxi XXXll LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS App. D.C. Appeal Cases, District of Columbia. App. Div. New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division Reports. Arch. Civ. Prax. Archiv fiir die civilistische Praxis (Germany) . Arch. Jud. Archivo judiciario (Brazil). Ariz. Arizona Reports. Ark. Arkansas Reports. Asp. Marit. Cas. Aspinall's Maritime Cases. Atl. Atlantic Reporter, National Reporter System (United States). -

Advisory Opinions and the Problem of Legal Authority

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 74 Issue 3 April 2021 Article 5 4-2021 Advisory Opinions and the Problem of Legal Authority Christian R. Burset Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Judges Commons, and the Jurisprudence Commons Recommended Citation Christian R. Burset, Advisory Opinions and the Problem of Legal Authority, 74 Vanderbilt Law Review 621 (2021) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol74/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Advisory Opinions and the Problem of Legal Authority Christian R. Burset* The prohibition against advisory opinions is fundamental to our understanding of federal judicial power, but we have misunderstood its origins. Discussions of the doctrine begin not with a constitutional text or even a court case, but a letter in which the Jay Court rejected President Washington’s request for legal advice. Courts and scholars have offered a variety of explanations for the Jay Court’s behavior. But they all depict the earliest Justices as responding to uniquely American concerns about advisory opinions. This Article offers a different explanation. Drawing on previously untapped archival sources, it shows that judges throughout the anglophone world—not only in the United States but also in England and British India— became opposed to advisory opinions in the second half of the eighteenth century. The death of advisory opinions was a global phenomenon, rooted in a period of anxiety about common-law authority. -

710 ATLANTIC REPORTER, 2D SERIES N. J. Suspensions. As

450 N. J. 710 ATLANTIC REPORTER, 2d SERIES suspensions. As modified, the judgment of of funding public schools, students chal- the Appellate Division is affirmed. lenged constitutionality of funding plan de- veloped by state in response to judicial For modification and affirmance—Chief mandate. The Supreme Court found plan Justice PORITZ and Justices HANDLER, facially constitutional but unconstitutional as POLLOCK, O’HERN, GARIBALDI, STEIN applied to special needs districts (SNDs), and COLEMAN—7. ordered parity funding as interim remedy, Opposed–none. and remanded for fact-finding hearings, 149 N.J. 145, 693 A.2d 417. Following conduct , of fact-finding hearings by the Superior Court, Chancery Division, King, J., and sub- mission of Report and Recommendation 153 N.J. 480 with respect thereto, the Supreme Court, S 480Raymond ABBOTT, a minor, by his Handler, J., held that: (1) elementary school Guardian Ad Litem, Frances ABBOTT; reform plan proposed by state education Arlene Figueroa, Frances Figueroa, and finance officials comported substantially Hector Figueroa, Orlando Figueroa, and with statutory and regulaStory481 policies de- Vivian Figueroa, minors, by their fining constitutional guarantee of thorough Guardian Ad Litem, Blanca Figueroa; and efficient education; (2) full-day kinder- Michael Hadley, a minor, by his Guard- garten plan comported substantially with ian Ad Litem, Lola Moore; Henry Ste- same statutory and regulatory policies and vens, Jr., a minor, by his Guardian Ad was essential to satisfaction of constitutional Litem, -

Draft Legislation (Wales) Bill

Number: WG34368 Welsh Government Consultation Document Draft Legislation (Wales) Bill Date of issue : 20 March 2018 Action required : Responses by 12 June 2018 Mae’r ddogfen yma hefyd ar gael yn Gymraeg. This document is also available in Welsh. © Crown Copyright Overview This document sets out the Welsh Government’s proposals to improve the accessibility and statutory interpretation of Welsh law, and seeks views on the Draft Legislation (Wales) Bill. How to respond Please send your written response to the address below or by email to the address provided. Further information Large print, Braille and alternative language and related versions of this document are available on documents request. Contact details For further information: Office of the Legislative Counsel Welsh Government Cathays Park Cardiff CF10 3NQ email: [email protected] telephone: 0300 025 0375 Data protection The Welsh Government will be data controller for any personal data you provide as part of your response to the consultation. Welsh Ministers have statutory powers they will rely on to process this personal data which will enable them to make informed decisions about how they exercise their public functions. Any response you send us will be seen in full by Welsh Government staff dealing with the issues which this consultation is about or planning future consultations. In order to show that the consultation was carried out properly, the Welsh Government intends to publish a summary of the responses to this document. We may also publish responses in full. Normally, the name and address (or part of the address) of the person or 1 organisation who sent the response are published with the response. -

Report of the Administrative Office of Pennsylvania Courts 2005

‘05 in Brief (listed chronologically) Pennsylvania’s minor court jurists, formerly called district judges, become known as magisterial district judges Report of the Chief Justice Ralph J. Administrative Office of Cappy forms the Pennsylvania Courts Interbranch Commis- sion for Gender, Racial 2005 and Ethnic Fairness to promote the equal application of the law for all citizens of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Supreme Court adopts Rules of Juvenile Procedure to establish for the first time uniform statewide procedures in juvenile courts that apply to all phases of delinquency cases that enter the state court system Justice Max Baer participates in “Changing Lives by Changing Systems: National Judicial Leadership Summit for Supreme Court of Pennsylvania the Protection of Chief Justice Ralph J. Cappy Children,” to work Justice Ronald D. Castille toward reforming the Justice Sandra Schultz Newman way abused and Justice Thomas G. Saylor neglected children’s Justice J. Michael Eakin cases proceed through Justice Max Baer the courts Justice Cynthia A. Baldwin Supreme Court issues order authorizing disciplinary pro- ceedings to be open to public review Pennsylvania begins development of a statewide education program for trial court judges who hear capital murder cases. The program, devel- oped with the Nevada- based National Judicial College, will be among the first of its kind in the nation. Kate Ford Elliott is elected president judge of Superior Court, becoming the first woman in Pennsyl- vania to lead an appellate court Title: (AOPC_Black.EPS) -

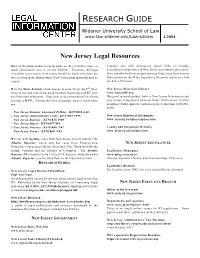

Research Guide

RESEARCH GUIDE Widener University School of Law www.law.widener.edu/Law-Library 4/2004 \ . New Jersey Legal Resources Most of the items in this research guide are free websites, since so Fantastic site with information and/or links to virtually much information now is on the Internet. However, the legal everything of importance in New Jersey government, plus more. researcher interested in New Jersey sho uld be aware that there are Here you will find links to such items as New Jersey Government two sections in the library where New Jersey print materials may be Publications on the W eb, Legislative Histories and even a link found: for Ask a Librarian. ! In the State Section which begins in aisle 30 on the 2nd floor. New Jersey State Law Library Items in the state section have call numbers beginning with KF, plus www.njstatelib.org the first initial of the state. Thus, New Jersey materials will be found Has good research guides, links to New Jersey Information and starting at KFN. Among the most frequently used of these items easy access to legislative histories from 1998 forward. Call for are: assistance with legislative histories prior to that time (609-292- 6230). – New Jersey Statutes Annotated (NJSA) - KFN1830.A42. – New Jersey Administrative Code - KFN1835 1995 New Jersey H istorical Documents – New Jersey Register - KFN1835 1969 www .state.nj.us/njfacts/njdocs.htm – New Jersey Digest - KFN1857.W4 – New Jersey Practice - KFN1880 .N47 County and Municipal Websites – New Jersey Forms - KFN1868 .N45 www .state.nj.us/localgov.htm ! In the U.S. -

Journal of Supreme Court History

Journal of Supreme Court History THE SUPREME COURT HISTORICAL SOCIETY THURGOOD MARSHALL Associate Justice (1967-1991) Journal of Supreme Court History PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE E. Barrett Prettyman, Jr. Chairman Donald B. Ayer Louis R. Cohen Charles Cooper Kenneth S. Geller James J. Kilpatrick Melvin I. Urofsky BOARD OF EDITORS Melvin I. Urofsky, Chairman Herman Belz Craig Joyce David O'Brien David J. Bodenhamer Laura Kalman Michael Parrish Kermit Hall Maeva Marcus Philippa Strum MANAGING EDITOR Clare Cushman CONSULTING EDITORS Kathleen Shurtleff Patricia R. Evans James J. Kilpatrick Jennifer M. Lowe David T. Pride Supreme Court Historical Society Board of Trustees Honorary Chairman William H. Rehnquist Honorary Trustees Harry A. Blackmun Lewis F. Powell, Jr. Byron R. White Chairman President DwightD.Opperman Leon Silverman Vice Presidents VincentC. Burke,Jr. Frank C. Jones E. Barrett Prettyman, Jr. Secretary Treasurer Virginia Warren Daly Sheldon S. Cohen Trustees George Adams Frank B. Gilbert Stephen W. Nealon HennanBelz Dorothy Tapper Goldman Gordon O. Pehrson Barbara A. Black John D. Gordan III Leon Polsky Hugo L. Black, J r. William T. Gossett Charles B. Renfrew Vera Brown Geoffrey C. Hazard, Jr. William Bradford Reynolds Wade Burger Judith Richards Hope John R. Risher, Jr. Patricia Dwinnell Butler William E. Jackson Harvey Rishikof Andrew M. Coats Rob M. Jones William P. Rogers William T. Coleman,1r. James 1. Kilpatrick Jonathan C. Rose F. Elwood Davis Peter A. Knowles Jerold S. Solovy George Didden IIJ Harvey C. Koch Kenneth Starr Charlton Dietz Jerome B. Libin Cathleen Douglas Stone John T. Dolan Maureen F. Mahoney Agnes N. Williams James Duff Howard T. -

Research Guide

Research Guide FINDING CASES I. HOW TO FIND A CASE WHEN YOU KNOW THE CITATION A. DECIPHERING LEGAL CITATIONS 1. CASE CITATIONS A case citation includes: the names of the parties, the volume number of the case reporter, the abbreviated name of the reporter, the page number where the case can be found, and the year of the decision. EXAMPLE: Reserve Insurance Co. v. Pisciotta, 30 Cal.3d 800 (1982). Reserve Insurance Co. v. Pisciotta = names of the parties 30 = volume number of the case reporter Cal. = abbreviated name of the case reporter, California Reports 3d = series number of the case reporter, California Reports 800 = page number of the case reporter (1982) = year of the decision 2. ABBREVIATIONS OF REPORTER NAMES The abbreviations used in citations can be deciphered by consulting: a. Prince’s Bieber Dictionary of Legal Abbreviations, 6th ed. (Ref. KF 246 .p74 2009) b. Black's Law Dictionary (Ref. KF 156 .B624 2009). This legal dictionary contains a table of abbreviations. Copies of Black's are located on dictionary stands throughout the library, as well as in the Reference Collection. 3. REPORTERS AND PARALLEL CITATIONS A case may be published in more than one reporter. Parallel citations indicate the different reporters publishing the same case. EXAMPLE: Reserve Insurance Co. v. Pisciotta, 30 Cal.3d 800, 180 Cal. Rptr. 628, 640 P.2d 764 (1982). 02/08/12 (Rev.) RG14 (OVER) This case will be found in three places: the "official" California Reports 3d (30 Cal. 3rd 800); and the two "unofficial" West reporters: the California Reporter (180 Cal. -

Advisory Opinions and the Influence of the Supreme Court Over American Policymaking

ADVISORY OPINIONS AND THE INFLUENCE OF THE SUPREME COURT OVER AMERICAN POLICYMAKING The influence and prestige of the federal judiciary derive primarily from its exercise of judicial review. This power to strike down acts of the so-called political branches or of state governments as repugnant to the Constitution — like the federal judicial power more generally — is circumscribed by a number of self-imposed justiciability doctrines, among the oldest and most foundational of which is the bar on advi- sory opinions.1 In accord with that doctrine, the federal courts refuse to advise other government actors or private individuals on abstract legal questions; instead, they provide their views only in the course of deciding live cases or controversies.2 This means that the Supreme Court will not consider whether potential legislative or executive ac- tion violates the Constitution when such action is proposed or even when it is carried out, but only when it is challenged by an adversary party in a case meeting various doctrinal requirements. So, if a legisla- tive coalition wishes to enact a law that might plausibly be struck down — such as the 2010 healthcare legislation3 — it must form its own estimation of whether the proposal is constitutional4 but cannot know for certain how the Court will ultimately view the law. The bar on advisory opinions is typically justified by reference to the separation of powers and judicial restraint: when courts answer le- gal questions outside the legal dispute-resolution process, they reach beyond the judicial role and assume a quasi-legislative character. But ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– 1 See Flast v. -

“Judicial Lockjaw”: the Debate Over Extrajudicial Activity

\\server05\productn\N\NYU\82-2\NYU205.txt unknown Seq: 1 18-APR-07 8:21 UNDERSTANDING “JUDICIAL LOCKJAW”: THE DEBATE OVER EXTRAJUDICIAL ACTIVITY LESLIE B. DUBECK* Federal judges are expected to conduct themselves differently than their counter- parts in the political branches. This Note considers the policy and historical rea- sons used to justify this different standard of conduct and concludes that these justifications are largely unsupported or overstated. These erroneous justifications obfuscate the debate over extrajudicial conduct and may result in a suboptimal level of extrajudicial activity. INTRODUCTION In 2006, news coverage of the State of the Union address included an analysis of the behavior of the four Supreme Court Justices in attendance. The Washington Post reported: “When Bush said ‘We love our freedom, and we will fight to keep it,’ Thomas looked at Roberts, who looked at Breyer, who gave an approving shrug; all four gentlemen stood and gave unanimous applause.”1 This brief episode illustrates three important points: First, there is a deep- seated understanding that federal judges are held to a different stan- dard of behavior than their counterparts in the legislative and execu- tive branches. Although audience members on both sides of the aisle were applauding, the Justices hesitated to do so. Second, it is difficult to identify exactly what is expected of judges. The Justices had to confer to determine whether applause would be appropriate. Third, the public is aware of the special behavior expected of judges. The Washington Post found it relevant enough to warrant a story the fol- lowing morning. Sixty years before this incident, Justice Felix Frankfurter noted that he suffered from “judicial lockjaw”2—a phenomenon of self- censorship that prevents judges from speaking about the judicial pro- cess and from pursuing extrajudicial activities.