Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Legislation (Wales) Bill

Number: WG34368 Welsh Government Consultation Document Draft Legislation (Wales) Bill Date of issue : 20 March 2018 Action required : Responses by 12 June 2018 Mae’r ddogfen yma hefyd ar gael yn Gymraeg. This document is also available in Welsh. © Crown Copyright Overview This document sets out the Welsh Government’s proposals to improve the accessibility and statutory interpretation of Welsh law, and seeks views on the Draft Legislation (Wales) Bill. How to respond Please send your written response to the address below or by email to the address provided. Further information Large print, Braille and alternative language and related versions of this document are available on documents request. Contact details For further information: Office of the Legislative Counsel Welsh Government Cathays Park Cardiff CF10 3NQ email: [email protected] telephone: 0300 025 0375 Data protection The Welsh Government will be data controller for any personal data you provide as part of your response to the consultation. Welsh Ministers have statutory powers they will rely on to process this personal data which will enable them to make informed decisions about how they exercise their public functions. Any response you send us will be seen in full by Welsh Government staff dealing with the issues which this consultation is about or planning future consultations. In order to show that the consultation was carried out properly, the Welsh Government intends to publish a summary of the responses to this document. We may also publish responses in full. Normally, the name and address (or part of the address) of the person or 1 organisation who sent the response are published with the response. -

Magna Carta and the Executive James Spigelman

Magna Carta and the Executive James Spigelman In 1215, Genghis Khan conquered Beijing on the way to creating the Mongol Empire. The 23rd of September 2015 was the 800th anniversary of the birth of his grandson, Kublai Khan, under whose imperial rule, as the founder of the Yuan dynasty, the extent of the China we know today was determined. 1215 was a big year for executive power. This 800th anniversary of Magna Carta should be approached with a degree of humility. Underlying themes In two earlier addresses during this year’s caravanserai of celebration,1 I have set out certain themes, each recognisably of constitutional significance, which underlie Magna Carta. In this address I wish to focus on four of those themes, as they developed over subsequent centuries, and to do so with a focus on the executive authority of the monarchy. The themes are: First, the king is subject to the law and also subject to custom which was, during that very period, in the process of being hardened into law. Secondly, the king is obliged to consult the political nation on important issues. Thirdly, the acts of the king are not simply personal acts. The king’s acts have an official character and, accordingly, are to be exercised in accordance with certain processes, and within certain constraints. Fourthly, the king must provide a judicial system for the administration of justice and all free men are entitled to due process of law. In my opinion, the long-term significance of Magna Carta does not lie in its status as a sacred text—almost all of which gradually became irrelevant. -

Quia Emptores, Subinfeudation, and the Decline of Feudalism In

QUIA EMPTORES, SUBINFEUDATION, AND THE DECLINE OF FEUDALISM IN MEDIEVAL ENGLAND: FEUDALISM, IT IS YOUR COUNT THAT VOTES Michael D. Garofalo Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2017 APPROVED: Christopher Fuhrmann, Committee Chair Laura Stern, Committee Member Mickey Abel, Minor Professor Harold Tanner, Chair of the Department of History David Holdeman, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Garofalo, Michael D. Quia Emptores, Subinfeudation, and the Decline of Feudalism in Medieval England: Feudalism, it is Your Count that Votes. Master of Science (History), August 2017, 123 pp., bibliography, 121 titles. The focus of this thesis is threefold. First, Edward I enacted the Statute of Westminster III, Quia Emptores in 1290, at the insistence of his leading barons. Secondly, there were precedents for the king of England doing something against his will. Finally, there were unintended consequences once parliament passed this statute. The passage of the statute effectively outlawed subinfeudation in all fee simple estates. It also detailed how land was able to be transferred from one possessor to another. Prior to this statute being signed into law, a lord owed the King feudal incidences, which are fees or services of various types, paid by each property holder. In some cases, these fees were due in the form of knights and fighting soldiers along with the weapons and armor to support them. The number of these knights owed depended on the amount of land held. Lords in many cases would transfer land to another person and that person would now owe the feudal incidences to his new lord, not the original one. -

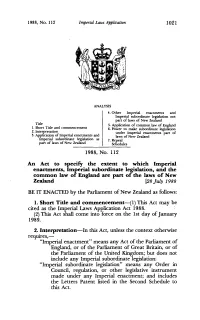

1988 No 112 Imperial Laws Application

1988, No. 112 Imperial Laws Application 1021 ANALYSIS 4. Other Imperial enactments and Imperial subordinate legislation not part of laws of New Zealand Title 5. Application of common law of England 1. Short Title and commencement 6. Power to make subordinate legislation 2. InteTretation under Imperial enactments part of 3. Application of Imperial enactments and laws of New Zealand Imperial subordinate legislation as 7. Repeal part of laws of New Zealand Scliedules 1988, No. 112 An Act to specify the extent to which Imperial enactments, Imperial subordinate legislation, and the common law of England are part of the laws of New Zealand [28 July 1988 BE IT ENACTED by the Parliament of New Zealand as follows: I. Short Tide and commencement-(1) This Act may be cited as the Imperial Laws Application Act 1988. : (2) This Act shall come into force on the 1st day of January 1989. 2. Interpretation-In this Act, unless the context otherwise requires,- "Imperial enactment" means any Act of the Parliament of England, or of the Parliament of Great Britain, or of the Parliament of the United Kingdom; but does not include any Imperial subordinate legislation: "Imperial subordinate legislation" means any Order in Council, regulation, or other legislative instrument made under any Imperial enactment; and includes the Letters Patent listed in the Second Schedule to this Act. 1022 Imperial Laws Application 1988, No. 112 8. Application of Imperial enactrnents and Imperial subordinate legislation as part of laws of New Zealand- (1) The Imperial enactments listed in the First Schedule to this Act, and the Imperial subordinate legislation listed in the Second Schedule to this Act, are hereby declared to be part of the laws of New Zealand. -

Imperial Laws Application Bill-98-1

IMPERIAL LAWS APPLICATION BILL NOTE THIS Bill is being introduced in its present form so as to give notice of the legislation that it foreshadows to Parliament and to others whom it may concern, and to provide those who may be interested with an opportunity to make representations and suggestions in relation to the contemplated legislation at this early formative stage. It is not intended that the Bill should pass in its present form. Work towards completing and polishing the draft, and towards reviewing the Imperial enactments in force in New Zealand, is proceeding under the auspices of the Law Reform Council. It is intended to introduce a revised Bill in due course, and to allow ample time for study of the revised Bill and making representations thereon. The enactment of a definitive statutory list of Imperial subordinate legis- lation in force in New Zealand is contemplated. This list could appropriately be included in the revised Bill, but this course is not intended to be followed if it is likely to cause appreciable delay. Provision for the additional list can be made by a separate Bill. Representations in relation to the present Bill may be made in accordance with the normal practice to the Clerk of the Statutes Revision Committee of tlie House of Representatives. No. 98-1 Price $2.40 IMPERIAL LAWS APPLICATION BILL EXPLANATORY NOTE THIS Bill arises out of a review that is in process of being made by the Law Reform Council of the Imperial enactments in force in New Zealand. The intention is that in due course the present Bill will be allowed to lapse, and a complete revised Bill will be introduced to take its place. -

Anglo-Saxon Constitutional History

English Legal History—Lecture Outline Wed., 6 Oct. Page 1 THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY: THE BARONS’ WARS AND THE LEGISLATION OF EDWARD I 1. Generalities about the 13th century. a. Gothic art and architecture—Reims, Notre Dame de Paris, Amiens, Westminster Abbey, Salisbury, and Lincoln Images: Durham cathedral, Salisbury cathedral, Chapter House at Winchester http://www.law.harvard.edu/faculty/cdonahue/courses/ELH/lectures/l09_cathedrals_1.pdf b. The high point of scholastic philosophy and theology—Albert the Great, Thomas Aquinas, Duns Scotus, Bonaventure c. New religious orders (Franciscans and Dominicans) d. Height of the temporal power of the papacy—Innocent III, Gregory IX, Innocent IV, ending with Boniface VIII at the end of the century e. The great glosses of Roman and canon law; Bracton and Beaumanoir Image: Bracton’s tomb http://www.law.harvard.edu/faculty/cdonahue/courses/ELH/slides/BractonTomb.jpg 2. English Chronology (Mats., p. V-15). Henry III — 1216–1272 — 57 years — died at age 65 Edward I — 1272–1307 — 35 years — died at age 68 1232 — End of Hubert de Burgh’s justiciarship 1258–59 — Provisions of Oxford, Provisions of Westminster, Treaty of Paris, the dynasty changes its name from Angevin to Plantegenet 1264 — Mise of Amiens, Battle of Lewes, Simon de Montfort’s 1st parliament 1265 — Simon de Montfort’s 2nd parliament, Battle of Evesham 1266 — Dictum of Kenilworth 1284 — Statute of Wales 1285 — Westminster II, De Donis 1290 — Westminster III, Quia Emptores 1292 — Judgment for John Baliol, beginning of Scottish wars 1295 — “Model” Parliament 1297 — Confirmatio cartarum 1303 — Treaty of Paris with Philip the Fair 3. -

Imperial Statutes in Australia and New Zealand Peter M

Bond Law Review Volume 2 | Issue 2 Article 4 1990 Imperial Statutes in Australia and New Zealand Peter M. McDermott Follow this and additional works at: http://epublications.bond.edu.au/blr This Article is brought to you by the Faculty of Law at ePublications@bond. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bond Law Review by an authorized administrator of ePublications@bond. For more information, please contact Bond University's Repository Coordinator. Imperial Statutes in Australia and New Zealand Abstract [extract] Upon the foundation of the colony of New South Wales the inhabitants, as subjects of the Crown, inherited the law of England. Section 24 of the Australian Courts Act 1828 (Imp) later provided that statutes which were in force in England, as at the date of the passing of the Act (ie 25 July 1828) to be applied in the courts of New South Wales and Van Dieman’s Land (later Tasmania) where they were applicable in the colony by reason of local conditions, and the administrative and judicial machinery then in existence. Sir Victor Windeyer commented that lawyers often regard the Australian Courts Act as ’the good root of title of our inheritance of the law of England’. However, Sir Victor Windeyer has pointed out that the source of the inheritance is the common law itself. The purpose of the Australian Courts Act was to fix a date, with certainty, up to when Imperial statutes were received. Keywords Imperial Statutes, Australia, New Zealand This article is available in Bond Law Review: http://epublications.bond.edu.au/blr/vol2/iss2/4 -

![Vetera Statuta Angliae [Old Statutes of England], Including the Magna](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5802/vetera-statuta-angliae-old-statutes-of-england-including-the-magna-4975802.webp)

Vetera Statuta Angliae [Old Statutes of England], Including the Magna

Vetera Statuta Angliae [Old Statutes of England], including the Magna Carta and other Statutes of the Realm In Latin and Law French, decorated manuscript on parchment England, after 1305 and probably before 1327 iii (modern paper) + ii (parchment) + 204 + iv (contemporary parchment) + iii (modern paper) folios on parchment, modern foliation in pencil, upper outer rectos, 1-115, 116-207, with unfoliated leaf in between ff. 15 and 16, complete (collation i6 ii-xxv8 xxvi8 [-7 and 8; two leaves canceled between ff. 203 and 204, with no loss of text]), quire signatures written in Roman numerals, at the ends of qq. viii, x, xii-xvi, xviii-xix, outer lower versos on, horizontal catchwords visible, partially cropped, on qq. ii-iv, x, xiii-xxii, xxiv, ruled in brown crayon with full-length horizontal and vertical bounding lines (justification 55-57 x 33-35 mm.), written in a fourteenth-century Anglicana hand on sixteen to twenty long lines, rubrics written in larger display Anglicana script, running titles on recto and verso, chapters identified in the margins, partially cropped, guide letters for initials, three- to four-line spaces left for initials, four-line red initial with red pen decoration extending into upper and left margins (f. 7), loss of text on f. 49v repaired in a different hand, some soiling of ff. 82v-83, edge of f. 90 slightly torn, water staining on ff. 154-155, 163-164, worming in the margins of ff. 124-129, hole in f. 1 with slight loss of text, loss of text on f. 89 due torn lower outer corner, text faded on f. -

Modernising English Land Law

International Law Research; Vol. 8, No. 1; 2019 ISSN 1927-5234 E-ISSN 1927-5242 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Modernising English Land Law Graham McBain1,2 1 Peterhouse, Cambridge, UK 2 Harvard Law School, USA Correspondence: Graham McBain, 21 Millmead Terrace, Guildford, Surrey GU2 4AT, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Received: January 22, 2019 Accepted: February 28, 2019 Online Published: March 5, 2019 doi:10.5539/ilr.v8n1p30 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ilr.v8n1p30 1. INTRODUCTION At present, the legal situation in respect of land in England and Wales is confusing. Title to most land in England and Wales is now registered. However, title to some 15% (or less) is still governed by older legal principles, including the need for title deeds. Further, there are many antiquated pieces of legislation relating to land still existing - various pieces of which are obsolete and others which should be re-stated in modern language. For a list of existing land legislation, see Appendices A-B. Antiquated (and obsolete) land legislation complicates the legal position as well as prevents the consolidation of English land law. Such has major financial implications since a clearer, consolidated, land law would help speed up land sales - including house purchases - and reduce costs for businesses and individuals. Also, old laws can (often) be a ‘trap for the unwary.’1 The purpose of this article is to consider various ancient pieces of land legislation and to argue that they should be repealed. In particular, this article argues for the repeal of the following: Inclosure Acts. -

Statute Law Repeals: Twentieth Report Draft Statute Law (Repeals) Bill

2015: 50 years promoting law reform Statute Law Repeals: Twentieth Report Draft Statute Law (Repeals) Bill LC357 / SLC243 The Law Commission and The Scottish Law Commission (LAW COM No 357) (SCOT LAW COM No 243) STATUTE LAW REPEALS: TWENTIETH REPORT DRAFT STATUTE LAW (REPEALS) BILL Presented to Parliament by the Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice by Command of Her Majesty Laid before the Scottish Parliament by the Scottish Ministers June 2015 Cm 9059 SG/2015/60 © Crown copyright 2015 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Print ISBN 9781474119337 Web ISBN 9781474119344 ID 20051507 05/15 49556 19585 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ii The Law Commission and the Scottish Law Commission were set up by the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Law Commissioners are: The Right Honourable Lord Justice Lloyd Jones, Chairman Professor Elizabeth Cooke1 Stephen Lewis Professor David Ormerod QC Nicholas Paines QC. The Chief Executive of the Law Commission is Elaine Lorimer. The Law Commission is located at 1st Floor, Tower, 52 Queen Anne’s Gate, London SW1H 9AG The Scottish Law Commissioners are: The Honourable Lord Pentland, Chairman Caroline Drummond David Johnston QC Professor Hector L MacQueen Dr Andrew J M Steven The Chief Executive of the Scottish Law Commission is Malcolm McMillan. -

KINGS, BARONS and JUSTICES the Making and Enforcement of Legislation in Thirteenth-Century England

KINGS, BARONS AND JUSTICES The Making and Enforcement of Legislation in Thirteenth-Century England PAUL BRAND All Souls College, Oxford publishe d by the pre ss syndicate of the unive rsity of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge unive rsity pre ss The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Cambridge University Press 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Bembo 11/12 pt. System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 0 521 37246 1 hardback CONTENTS List of tables page xii Preface xiii List of abbreviations xvi introduction 1 Part I: Politics and the legislative reform of the common law: from the Provisions of Westminster of 1259 to the Statute of Marlborough of 1267 1 the making of the provisions of we stminste r: the proce ss of drafting and the ir political conte xt 15 The establishment of the Committee of Twenty-four 16 The work of the Committee of Twenty-four 18 The ‘Petition of the Barons’ 20 The continuation of the -

UNBOUND an Annual Review of Legal History and Rare Books

UNBOUND An Annual Review of Legal History and Rare Books Journal of the Legal History and Rare Books Special Interest Section of the American Association of Law Libraries Volume 1 2008 UNBOUND An Annual Review of Legal History and Rare Books Unbound: An Annual Review of Legal History and Rare Books is published yearly by the Legal History and Rare Books Special Interest Section of the American Association of Law Libraries BOARD OF EDITORS Mark Podvia, Editor-in-Chief Associate Law Librarian and Archivist Dickinson School of Law Library of the Pennsylvania State University 150 South College St. Carlisle, PA 17013 Phone: (717)240-5015 Email: [email protected] Jennie Meade, Articles Editor Joel Fishman, Ph.D., Book Review Bibliographerand Rare Books Editor Librarian Assistant Director for Lawyer Services George Washington University Duquesne University Center for Legal Jacob Burns Law Library Information/Allegheny Co. Law 716 20th St, N.W. Library Washington, DC 20052 921 City-County Building Phone (202)994-6857 414 Grant Street [email protected] Pittsburgh, PA 15219 Phone (412)350-5727 Kurt X. Metzmeier, Articles [email protected] Editor and Webmaster Sarah Yates, Special Collections Associate Director Cataloging Editor University of Louisville Law Cataloging Librarian Library University of Minnesota Law Belknap Campus Library 2301 S. Third 229 19th Ave. S. Louisville, KY 40292 Minneapolis, MN 55455 Phone (502)852-6082 Phone (612)625-1898 [email protected] [email protected] Cover Illustration: This depiction of an American Bison, engraved by David Humphreys, was first published in Hughes Kentucky Reports (1803). It was adopted as symbol of the Legal History and Rare Books Special Interest Section in 2007.