Imperial Statutes in Australia and New Zealand Peter M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statute Law Repeals: Twentieth Report Draft Statute Law (Repeals) Bill

2015: 50 years promoting law reform Statute Law Repeals: Twentieth Report Draft Statute Law (Repeals) Bill LC357 / SLC243 The Law Commission and The Scottish Law Commission (LAW COM No 357) (SCOT LAW COM No 243) STATUTE LAW REPEALS: TWENTIETH REPORT DRAFT STATUTE LAW (REPEALS) BILL Presented to Parliament by the Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice by Command of Her Majesty Laid before the Scottish Parliament by the Scottish Ministers June 2015 Cm 9059 SG/2015/60 © Crown copyright 2015 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Print ISBN 9781474119337 Web ISBN 9781474119344 ID 20051507 05/15 49556 19585 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ii The Law Commission and the Scottish Law Commission were set up by the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Law Commissioners are: The Right Honourable Lord Justice Lloyd Jones, Chairman Professor Elizabeth Cooke1 Stephen Lewis Professor David Ormerod QC Nicholas Paines QC. The Chief Executive of the Law Commission is Elaine Lorimer. The Law Commission is located at 1st Floor, Tower, 52 Queen Anne’s Gate, London SW1H 9AG The Scottish Law Commissioners are: The Honourable Lord Pentland, Chairman Caroline Drummond David Johnston QC Professor Hector L MacQueen Dr Andrew J M Steven The Chief Executive of the Scottish Law Commission is Malcolm McMillan. -

Draft Legislation (Wales) Bill

Number: WG34368 Welsh Government Consultation Document Draft Legislation (Wales) Bill Date of issue : 20 March 2018 Action required : Responses by 12 June 2018 Mae’r ddogfen yma hefyd ar gael yn Gymraeg. This document is also available in Welsh. © Crown Copyright Overview This document sets out the Welsh Government’s proposals to improve the accessibility and statutory interpretation of Welsh law, and seeks views on the Draft Legislation (Wales) Bill. How to respond Please send your written response to the address below or by email to the address provided. Further information Large print, Braille and alternative language and related versions of this document are available on documents request. Contact details For further information: Office of the Legislative Counsel Welsh Government Cathays Park Cardiff CF10 3NQ email: [email protected] telephone: 0300 025 0375 Data protection The Welsh Government will be data controller for any personal data you provide as part of your response to the consultation. Welsh Ministers have statutory powers they will rely on to process this personal data which will enable them to make informed decisions about how they exercise their public functions. Any response you send us will be seen in full by Welsh Government staff dealing with the issues which this consultation is about or planning future consultations. In order to show that the consultation was carried out properly, the Welsh Government intends to publish a summary of the responses to this document. We may also publish responses in full. Normally, the name and address (or part of the address) of the person or 1 organisation who sent the response are published with the response. -

Fourteenth Report: Draft Statute Law Repeals Bill

The Law Commission and The Scottish Law Commission (LAW COM. No. 211) (SCOT. LAW COM. No. 140) STATUTE LAW REVISION: FOURTEENTH REPORT DRAFT STATUTE LAW (REPEALS) BILL Presented to Parliament by the Lord High Chancellor and the Lord Advocate by Command of Her Majesty April 1993 LONDON: HMSO E17.85 net Cm 2176 The Law Commission and the Scottish Law Commission were set up by the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the Law. The Law Commissioners are- The Honourable Mr. Justice Brooke, Chairman Mr Trevor M. Aldridge, Q.C. Mr Jack Beatson Mr Richard Buxton, Q.C. Professor Brenda Hoggett, Q.C. The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Collon. Its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London WClN 2BQ. The Scottish Law Commissioners are- The Honourable Lord Davidson, Chairman .. Dr E.M. Clive Professor P.N. Love, C.B.E. Sheriff I.D.Macphail, Q.C. Mr W.A. Nimmo Smith, Q.C. The Secretary of the Scottish Law Commission is Mr K.F. Barclay. Its offices are at 140 Causewayside, Edinburgh EH9 1PR. .. 11 THE LAW COMMISSION AND THE SCOTTISH LAW COMMISSION STATUTE LAW REVISION: FOURTEENTH REPORT Draft Statute Law (Repeals) Bill To the Right Honourable the Lord Mackay of Clashfern, Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, and the Right Honourable the Lord Rodger of Earlsferry, Q.C., Her Majesty's Advocate. In pursuance of section 3(l)(d) of the Law Commissions Act 1965, we have prepared the draft Bill which is Appendix 1 and recommend that effect be given to the proposals contained in it. -

Appellant) V the Scottish Ministers (Respondent) (Scotland

Michaelmas Term [2012] UKSC 58 On appeal from: [2011] CSIH 19; [2008] CSOH 123 JUDGMENT RM (AP) (Appellant) v The Scottish Ministers (Respondent) (Scotland) before Lord Hope, Deputy President Lady Hale Lord Wilson Lord Reed Lord Carnwath JUDGMENT GIVEN ON 28 November 2012 Heard on 23 October 2012 Appellant Respondent Jonathan Mitchell QC James Mure QC Lorna Drummond QC Jonathan Barne (Instructed by Frank (Instructed by Scottish Irvine Solicitors Ltd) Government Legal Directorate Litigation Division) LORD REED (with whom Lord Hope, Lady Hale, Lord Wilson and Lord Carnwath agree) 1. This appeal raises a question as to the effect of a commencement provision in a statute which provides that provisions “shall come into force” on a specified date, and a consequential question as to the effect of a provision conferring upon Ministers the power to make regulations, where the provisions which are subject to the commencement provision cannot come into effective operation unless such regulations have been made. The legislation 2. These questions arise in relation to the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003 (“the 2003 Act”). The relevant substantive provisions are contained in Chapter 3 of Part 17, comprising sections 264 to 273. That Chapter is concerned with the detention of patients in conditions of excessive security. 3. Section 264 is headed “Detention in conditions of excessive security: state hospitals”. It applies where a patient's detention in a state hospital is authorised by one of the measures listed in subsection (1)(a) to (d): that is to say, a compulsory treatment order, a compulsion order, a hospital direction or a transfer for treatment direction. -

Statutory Instrument Practice

Statutory Instrument Practice A guide to help you prepare and publish Statutory Instruments and understand the Parliamentary procedures relating to them - 5th edition (November 2017) Statutory Instrument Practice Page i Statutory Instrument Practice is published by The National Archives © Crown copyright 2017 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to: [email protected]. Statutory Instrument Practice Page ii Preface This is the fifth edition of Statutory Instrument Practice (SIP) and replaces the edition published in November 2006. This edition has been prepared by the Legislation Services team at The National Archives. We will contact you regularly to make sure that this guide continues to meet your needs, and remains accurate. If you would like to suggest additional changes to us, please email them to the SI Registrar. Thank you to all of the contributors who helped us to update this edition. You can download SIP from: https://publishing.legislation.gov.uk/tools/uksi/si-drafting/si- practice. November 2017 Statutory Instrument Practice Page iii Contents PREFACE ............................................................................................................................. 3 CONTENTS .......................................................................................................................... 4 PART 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... -

Magna Carta and the Executive James Spigelman

Magna Carta and the Executive James Spigelman In 1215, Genghis Khan conquered Beijing on the way to creating the Mongol Empire. The 23rd of September 2015 was the 800th anniversary of the birth of his grandson, Kublai Khan, under whose imperial rule, as the founder of the Yuan dynasty, the extent of the China we know today was determined. 1215 was a big year for executive power. This 800th anniversary of Magna Carta should be approached with a degree of humility. Underlying themes In two earlier addresses during this year’s caravanserai of celebration,1 I have set out certain themes, each recognisably of constitutional significance, which underlie Magna Carta. In this address I wish to focus on four of those themes, as they developed over subsequent centuries, and to do so with a focus on the executive authority of the monarchy. The themes are: First, the king is subject to the law and also subject to custom which was, during that very period, in the process of being hardened into law. Secondly, the king is obliged to consult the political nation on important issues. Thirdly, the acts of the king are not simply personal acts. The king’s acts have an official character and, accordingly, are to be exercised in accordance with certain processes, and within certain constraints. Fourthly, the king must provide a judicial system for the administration of justice and all free men are entitled to due process of law. In my opinion, the long-term significance of Magna Carta does not lie in its status as a sacred text—almost all of which gradually became irrelevant. -

Quia Emptores, Subinfeudation, and the Decline of Feudalism In

QUIA EMPTORES, SUBINFEUDATION, AND THE DECLINE OF FEUDALISM IN MEDIEVAL ENGLAND: FEUDALISM, IT IS YOUR COUNT THAT VOTES Michael D. Garofalo Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2017 APPROVED: Christopher Fuhrmann, Committee Chair Laura Stern, Committee Member Mickey Abel, Minor Professor Harold Tanner, Chair of the Department of History David Holdeman, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Garofalo, Michael D. Quia Emptores, Subinfeudation, and the Decline of Feudalism in Medieval England: Feudalism, it is Your Count that Votes. Master of Science (History), August 2017, 123 pp., bibliography, 121 titles. The focus of this thesis is threefold. First, Edward I enacted the Statute of Westminster III, Quia Emptores in 1290, at the insistence of his leading barons. Secondly, there were precedents for the king of England doing something against his will. Finally, there were unintended consequences once parliament passed this statute. The passage of the statute effectively outlawed subinfeudation in all fee simple estates. It also detailed how land was able to be transferred from one possessor to another. Prior to this statute being signed into law, a lord owed the King feudal incidences, which are fees or services of various types, paid by each property holder. In some cases, these fees were due in the form of knights and fighting soldiers along with the weapons and armor to support them. The number of these knights owed depended on the amount of land held. Lords in many cases would transfer land to another person and that person would now owe the feudal incidences to his new lord, not the original one. -

The Law Commission and the Scottish Law Commission (LAW COM

The Law Commission and The Scottish Law Commission (LAW COM. No. 21) (SCOT. LAW COM. No. 11) THE WTERPRETATION OF STATUTE§ Laid before Parliament by the Lord High Chancellor, the Secretary of State for Scotland and the Lord Advocate pursuant to section 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 9th June 1969 LONDON HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE Reprinted 1 9 7 4 256 4Op net The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law other than the law of Scotland or of any law of Northern Ireland which the Parliament of Northern Ireland has power to amend. The Commissioners are: The Honourable Mr. Justice Scarman, O.B.E., Chairman. Mr. L. C. B. Gower. Mr. Neil Lawson, Q.C. Mr. Norman S. Marsh, Q.C. Mr. Andrew Martin, Q.C. Mr. Arthur Stapleton Cotton is a special consultant to the Commission. The Secretary of the Commission is Mr. J. M. Cartwright Sharp, and its offices are at Lacon House, Theobald’s Road, London, W.C.l. The Scottish Law Commission was set up by section 2 of the Law Com- missions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the Law of Scotland. The Commissioners are: The Honourable Lord Kilbrandon, Chairman. Professor A. E. Anton. Professor J. M. Halliday. Mr. A. M. Johnston, Q.C. Professor T. B. Smith, Q.C. I The Secretary of the Commission is Mr. A. G. -

Criminal Law Act 1977

Criminal Law Act 1977 CHAPTER 45 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I CONSPIRACY Section 1. The offence of conspiracy. 2. Exemptions from liability for conspiracy. 3. Penalties for conspiracy. 4. Restrictions on the institution of proceedings for conspiracy. 5. Abolitions, savings, transitional provisions, consequential amendment and repeals. PART II OFFENCES RELATING TO ENTERING AND REMAINING ON PROPERTY 6. Violence for securing entry. 7. Adverse occupation of residential premises. 8. Trespassing with a weapon of offence. 9. Trespassing on premises of foreign missions, etc. 10. Obstruction of court officers executing process for possession against unauthorised occupiers. 11. Power of entry for the purposes of this Part of this Act. 12. Supplementary provisions. 13. Abolitions and repeals. PART III CRIMINAL PROCEDURE, PENALTIES, ETC. Preliminary 14. Preliminary. Allocation of offences to classes as regards mode of trial 15. Offences which are to become triable only summarily. A ii c. 45 Criminal Law Act 1977 Section 16. Offences which are to become triable either way. 17. Offence which is to become triable only on indictment. Limitation of time 18. Provisions as to time-limits on summary proceedings for indictable offences. Procedure for determining mode of trial of offences triable either way 19. Initial procedure on information for offence triable either way. 20. Court to begin by considering which mode of trial appears more suitable. 21. Procedure where summary trial appears more suitable. 22. Procedure where trial on indictment appears more suitable. 23. Certain offences triable either way to be tried summarily if value involved is small. 24. Power of court, with consent of legally represented accused, to proceed in his absence. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-11137-9 - Writing to the King: Nation, Kingship, and Literature in England, 1250-1350 David Matthews Excerpt More information Introduction the knight of the letter: writing to the king As King Edward II celebrated the feast of Pentecost in 1317 in Westminster Hall with his magnates, a surprising visitor arrived: A certain woman, dressed and equipped in the guise of an entertainer, mounted on a good horse bearing an entertainer’s medallions, entered the said hall, circu- lated amongst the tables in the mode of an entertainer, ascended to the dais by the step, boldly approached the royal table, laid down a certain letter before the king, and, hauling on the bridle, having greeted the guests, without commotion or hindrance departed on the horse. At which the great as well as the less, looking by turns at one another, and judging themselves to be scorned by such a deed of daring and female mockery, sharply rebuked the doorkeepers and stewards concerning that entry and exit. But they, thrown into perplexity, made a virtue of necessity, saying that it was not the practice of the king to deny access, on such a solemn feast-day, to any minstrel wishing to enter the palace. At length the woman is sought out, captured, and put in prison; asked why she had acted thus, she boldly confessed that she had been instructed to do this by a certain knight, and had been hired for money. The knight is taken and is brought before the King, summoned concerning the one sent before. -

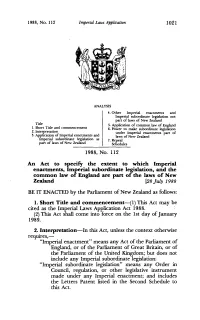

1988 No 112 Imperial Laws Application

1988, No. 112 Imperial Laws Application 1021 ANALYSIS 4. Other Imperial enactments and Imperial subordinate legislation not part of laws of New Zealand Title 5. Application of common law of England 1. Short Title and commencement 6. Power to make subordinate legislation 2. InteTretation under Imperial enactments part of 3. Application of Imperial enactments and laws of New Zealand Imperial subordinate legislation as 7. Repeal part of laws of New Zealand Scliedules 1988, No. 112 An Act to specify the extent to which Imperial enactments, Imperial subordinate legislation, and the common law of England are part of the laws of New Zealand [28 July 1988 BE IT ENACTED by the Parliament of New Zealand as follows: I. Short Tide and commencement-(1) This Act may be cited as the Imperial Laws Application Act 1988. : (2) This Act shall come into force on the 1st day of January 1989. 2. Interpretation-In this Act, unless the context otherwise requires,- "Imperial enactment" means any Act of the Parliament of England, or of the Parliament of Great Britain, or of the Parliament of the United Kingdom; but does not include any Imperial subordinate legislation: "Imperial subordinate legislation" means any Order in Council, regulation, or other legislative instrument made under any Imperial enactment; and includes the Letters Patent listed in the Second Schedule to this Act. 1022 Imperial Laws Application 1988, No. 112 8. Application of Imperial enactrnents and Imperial subordinate legislation as part of laws of New Zealand- (1) The Imperial enactments listed in the First Schedule to this Act, and the Imperial subordinate legislation listed in the Second Schedule to this Act, are hereby declared to be part of the laws of New Zealand. -

Statute Law Revision: Sixteenth Report Draft Statute Law (Repeals) Bill

LAW COMMISSION SCOTTISH LAW COMMISSION STATUTE LAW REVISION: SIXTEENTH REPORT DRAFT STATUTE LAW (REPEALS) BILL CONTENTS Paragraph Page REPORT 1 APPENDIX 1: DRAFT STATUTE LAW (REPEALS) BILL 2 APPENDIX 2: EXPLANATORY NOTE ON THE DRAFT BILL 46 Clauses 1 – 3 46 Schedule 1: Repeals 47 PART I: Administration of Justice 47 Group 1 - Sheriffs 1.1 47 Group 2 - General Repeals 1.4 48 PART II: Ecclesiastical Law 51 Group 1 - Ecclesiastical Leases 2.1 51 Group 2 - Tithe Acts 2.6 53 PART III: Education 57 Group 1 - Public Schools 3.1 57 Group 2 - Universities 3.2 57 PART IV: Finance 60 Group 1 - Colonial Stock 4.1 60 Group 2 - Land Commission 4.4 60 Group 3 - Development of Tourism 4.6 61 Group 4 - Loan Societies 4.7 62 Group 5 - General Repeals 4.9 62 PART V: Hereford and Worcester 65 Statutory Undertaking Provisions 5.8 68 Protective Provisions 5.15 71 Bridges 5.16 72 Miscellaneous Provisions 5.24 75 PART VI: Inclosure Acts 77 iii Paragraph Page PART VII: Scottish Local Acts 83 Group 1 - Aid to the Poor, Charities and Private Pensions 7.7 84 Group 2 - Dog Wardens 7.9 85 Group 3 - Education 7.12 86 Group 4 - Insurance Companies 7.13 86 Group 5 - Local Authority Finance 7.14 87 Group 6 - Order Confirmation Acts 7.19 89 Group 7 - Oyster and Mussel Fisheries 7.22 90 Group 8 - Other Repeals 7.23 90 PART VIII: Slave Trade Acts 92 PART IX: Statutes 102 Group 1 - Statute Law Revision Acts 9.1 102 Group 2 - Statute Law (Repeals) Acts 9.6 103 PART X: Miscellaneous 106 Group 1 - Stannaries 10.1 106 Group 2 - Sea Fish 10.3 106 Group 3 - Sewers Support 10.4 107 Group 4 - Agricultural Research 10.5 108 Group 5 - General Repeals 10.6 108 Schedule 2: Consequential and connected provisions 115 APPENDIX 3: CONSULTEES ON REPEAL OF LEGISLATION 117 PROPOSED IN SCHEDULE 1, PART V iv THE LAW COMMISSION AND THE SCOTTISH LAW COMMISSION STATUTE LAW REVISION: SIXTEENTH REPORT Draft Statute Law (Repeals) Bill To the Right Honourable the Lord Irvine of Lairg, Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, and the Right Honourable the Lord Hardie, QC, Her Majesty’s Advocate 1.