Sports Volunteering in England, 2002 Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on the Changes in the Number of Participating Athletes in the National Disabled Games Between 2008 and 2012, Using the Latent Growth Model

A Study on the Changes in the Number of Participating Athletes in the National Disabled Games between 2008 and 2012, Using the Latent Growth Model Cheng-Lung Wu, Department of Marine Sports and Recreation, National Penghu University of Science and Technology, Taiwan ABSTRACT This study employed the Latent Growth Model (LGM) to analyze changes in the number of participating athletes in the National Disabled Games from all cities and counties in Taiwan between 2008 and 2012. The aim was to examine the changes and dynamic process of the participating athletes at different times. The result of the study indicates that between 2008 and 2012, the initial average of the number of participating athletes in the National Disabled Games is 53.23, and the average growth is 3.93; the respective t values are 6.78 and 2.81, which are both statistically significant (*p<.05). In other words, the average number of participating athletes in the National Disabled Games in 2008 was 53.23, and continued to grow at an average rate of 3.93 persons per year. There was significant growth in the number of participating athletes between 2008 and 2012 in all cities and counties. In addition, there was significant difference in the growth rates among different cities and counties. Keywords: Latent Growth Model (LGM), physical and mental impairments, National Disabled Games INTRODUCTION It has become a global trend to improve the welfare of the physically and mentally challenged. The degree to which a country is capable of providing adequate care and opportunities for its physically and mentally challenged citizens is also an important index in evaluating its overall development. -

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY QUESTION No. 2026 for WRITTEN REPLY

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY QUESTION No. 2026 FOR WRITTEN REPLY DATE OF PUBLICATION IN INTERNAL QUESTION PAPER: Mr G R Krumbock (DA) to ask the Minister of Sports, Arts and Culture: (1) When last was each national competition of each South African sports federation held; (2) What (a) total number of national federations has the SA Sports Confederation and Olympic Committee (SASCOC) closed down since its establishment and (b) were the reasons in each case; (3) what (a) total number of applications for membership has SASCOC refused since its inception and (b) were the reasons in each case? NW2587E 1 REPLY (1) The following are the details on national competitions as received from the National Federations that responded; National Federations Championship(s) Dates South African Youth Championships October 2019 Wrestling Federation Senior, Junior and Cadet June 2019 Presidents and Masters March 2019 South African South African Equipped Powerlifting Championships 22 February 2020 Powerlifting Federation - Johannesburg Roller Sport South SA Artistic Roller Skating 17 - 19 May 2019 Africa SA Inline Speed skating South African Hockey Indoor Inter Provincial Tournament 11-14 March 2020 Association Cricket South Africa Proteas (Men) – Tour to India, match was abandoned 12 March 2020 without a ball bowled (Covid19 Impacted the rest of the tour). Proteas (Women)- ICC T20 Women’s World Cup 5 March 2020) (Semifinal Tennis South Africa Seniors National Competition 7-11 March 2020 South African Table Para Junior and Senior Championship 8-10 August 2019 Tennis Board -

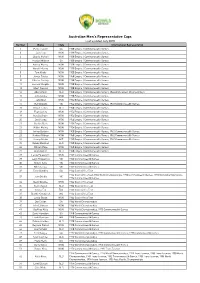

2018 Australian Representative Numbers (Men) Games Tally

Australian Men's Representative Caps Last updated July 2018 Number Name State International Representation 1 Percy Hutton SA 1938 Empire / Commonwealth Games 3 Jack Low NSW 1938 Empire / Commonwealth Games 4 Charlie McNeil NSW 1938 Empire / Commonwealth Games 5 Howard Mildren SA 1938 Empire / Commonwealth Games 6 Aubrey Murray NSW 1938 Empire / Commonwealth Games 7 Harold Murray NSW 1938 Empire / Commonwealth Games 8 Tom Kinder NSW 1938 Empire / Commonwealth Games 8 James Cobley NSW 1950 Empire / Commonwealth Games 10 Charles Cordaiy NSW 1950 Empire / Commonwealth Games 11 Leonard Knights NSW 1950 Empire / Commonwealth Games 13 Albert Newton NSW 1950 Empire / Commonwealth Games 14 Albert Palm QLD 1950 Empire / Commonwealth Games, 1966 World Bowls Championships 15 John Cobley NSW 1950 Empire / Commonwealth Games 16 John Bird NSW 1954 Empire / Commonwealth Games 17 Glyn Bosisto VIC 1954 Empire / Commonwealth Games, 1958 Commonwealth Games 18 Robert Lewis QLD 1950 Empire / Commonwealth Games 18 Elgar Collins NSW 1954 Empire / Commonwealth Games 19 Neville Green NSW 1954 Empire / Commonwealth Games 20 David Long NSW 1954 Empire / Commonwealth Games 21 Charles Beck NSW 1954 Empire / Commonwealth Games 21 Walter Maling NSW 1954 Empire / Commonwealth Games 22 Arthur Baldwin NSW 1958 Empire / Commonwealth Games, 1962 Commonwealth Games 23 Richard Gillings NSW 1958 Empire / Commonwealth Games, 1962 Commonwealth Games 24 George Makin ACT 1958 Empire / Commonwealth Games, 1962 Commonwealth Games 25 Ronald Marshall QLD 1958 Empire / Commonwealth -

Animal and Sporting Paintings in the Penkhus Collection: the Very English Ambience of It All

Animal and Sporting Paintings in the Penkhus Collection: The Very English Ambience of It All September 12 through November 6, 2016 Hillstrom Museum of Art SEE PAGE 14 Animal and Sporting Paintings in the Penkhus Collection: The Very English Ambience of It All September 12 through November 6, 2016 Opening Reception Monday, September 12, 2016, 7–9 p.m. Nobel Conference Reception Tuesday, September 27, 2016, 6–8 p.m. This exhibition is dedicated to the memory of Katie Penkhus, who was an art history major at Gustavus Adolphus College, was an accomplished rider and a lover of horses who served as co-president of the Minnesota Youth Quarter Horse Association, and was a dedicated Anglophile. Hillstrom Museum of Art HILLSTROM MUSEUM OF ART 3 DIRECTOR’S NOTES he Hillstrom Museum of Art welcomes this opportunity to present fine artworks from the remarkable and impressive collection of Dr. Stephen and Mrs. Martha (Steve and Marty) T Penkhus. Animal and Sporting Paintings in the Penkhus Collection: The Very English Ambience of It All includes sixty-one works that provide detailed glimpses into the English countryside, its occupants, and their activities, from around 1800 to the present. Thirty-six different artists, mostly British, are represented, among them key sporting and animal artists such as John Frederick Herring, Sr. (1795–1865) and Harry Hall (1814–1882), and Royal Academicians James Ward (1769–1859) and Sir Alfred Munnings (1878–1959), the latter who served as President of the Royal Academy. Works in the exhibit feature images of racing, pets, hunting, and prized livestock including cattle and, especially, horses. -

2011-02-10-Ocean

About the 2011 Oceania Speed Skating Championships LOCATION: Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia The Gold Coast features immaculate beaches running almost the entire length of the regions coastline which faces the beautiful blue Pacific Ocean. Match this with a favorable climate, endless attractions, nightlife, dining, friendly people, along with a safe environment, and you have Australias favourite holiday destination that's open to the world. The Gold Coast region is located 70kms south of Queensland's capital city, Brisbane, and almost 1000km's north of the capital of New South Wales, Sydney. It has an estimated population of 480,000 and is Australia's sixth largest city. At the center of the Gold Coast region is the popular and well known suburb of Surfers Paradise. Inland from the beaches and behind the city, there are magnificent National Parks - Springbrook, Lamington and Tamborine which feature World Heritage protected areas. These scenic sub-tropical rainforests are visitor friendly with picnic areas, short and long nature walks, amazing natural flora and fauna, and spectacular lookouts that gaze out across the hinterland, the city and out to the expanse of the ocean. The Hinterland and Mt Tamborine is also popular for it's wineries. The Climate on the Gold Coast is a comfortable sub-tropical climate averaging in the 20's and is enjoyable all year round. Autumn is still warm to hot during the days and slightly cooler at nights. Humidity drops and there is less rain. Autumn in the Gold Coast is similar to Spring - it's a great time to visit. The weather makes it favorable for a vast range of attractions and activities including four big theme parks that provide hours and hours, if not days, of entertainment value with something on offer for everyone. -

AIS Framework for Rebooting Sport

Appendix B — Minimum baseline of standards for Level A, B, C activities for high performance/professional sport 1 THE AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF SPORT (AIS) FRAMEWORK FOR REBOOTING SPORT IN A COVID-19 ENVIRONMENT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY May 2020 The Australian Institute of Sport (AIS) Framework for Rebooting Sport in a COVID-19 Environment — Executive Summary 2 INTRODUCTION Sport makes an important contribution to the physical, psychological and emotional well-being of Australians. The economic contribution of sport is equivalent to 2–3% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The COVID-19 pandemic has had devastating effects on communities globally, leading to significant restrictions on all sectors of society, including sport. Resumption of sport can significantly contribute to the re-establishment of normality in Australian society. The Australian Institute of Sport (AIS), in consultation with sport partners (National Institute Network (NIN) Directors, NIN Chief Medical Officers (CMOs), National Sporting Organisation (NSO) Presidents, NSO Performance Directors and NSO CMOs), has developed a framework to inform the resumption of sport. National Principles for Resumption of Sport were used as a guide in the development of ‘the AIS Framework for Rebooting Sport in a COVID-19 Environment’ (the AIS Framework); and based on current best evidence, and guidelines from the Australian Federal Government, extrapolated into the sporting context by specialists in sport and exercise medicine, infectious diseases and public health. The principles outlined in this document apply equally to high performance/professional level, community competitive and individual passive (non-contact) sport. The AIS Framework is a timely tool for ‘how’ reintroduction of sport activity will occur in a cautious and methodical manner, to optimise athlete and community safety. -

State of Play: 2017 Report by the Aspen Institute’S Project Play Our Response to Nina and Millions of Kids

STATE OF PLAY 2017 TRENDS AND DEVELOPMENTS 2017 THE FRAMEWORK SPORT as defined by Project Play THE VISION Sport for All, Play for Life: An America in which A Playbook to Get Every All forms of physical all children have the Kid in the Game activity which, through organized opportunity to be by the Aspen Institute or casual play, aim to active through sports Project Play express or improve youthreport.projectplay.us physical fitness and mental well-being. Participants may be motivated by intrinsic or external rewards, and competition may be with others or themselves (personal challenge). ALSO WORTH READING Our State of Play reports on cities and regions where we’re working. Find them at www.ProjectPlay.us ANALYSIS AND RECOMMENDATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 SCOREBOARD 3 THE 8 PLAYS 7 CALL FOR LEADERSHIP 16 NEXT 18 ENDNOTES 20 INTRODUCTION Nina Locklear is a never-bashful 11-year-old from Baltimore with common sense well beyond her years. She plays basketball, serves as a junior coach at her school to motivate other kids, and doesn’t hesitate to tell adults why sports are so valuable. “It’s fun when you meet other people that you don’t know,” Nina told 400 sport, health, policy, industry and media leaders at the 2017 Project Play Summit. “I’m seeing all of you right now. I don’t know any of you, none of you. But now that I see you I’m like, ‘You’re family.’ It (doesn’t) matter where you live, what you look like, y’all my family and I’m gonna remember that.” If you’re reading this, you’re probably as passionate as Nina about the power of sports to change lives. -

OHSAA Handbook for Match Type)

2021-22 Handbook for Member Schools Grades 7 to 12 CONTENTS About the OHSAA ...............................................................................................................................................................................4 Who to Contact at the OHSAA ...........................................................................................................................................................5 OHSAA Board of Directors .................................................................................................................................................................6 OHSAA Staff .......................................................................................................................................................................................7 OHSAA Board of Directors, Staff and District Athletic Boards Listing .............................................................................................8 OHSAA Association Districts ...........................................................................................................................................................10 OHSAA Affiliated Associations ........................................................................................................................................................11 Coaches Associations’ Proposals Timelines ......................................................................................................................................11 2021-22 OHSAA Ready Reference -

2019-2020 ACADEMIES - - TRIATHLON - INTRODUCTION Because Sport Is a Family Affair, Sport Village Has Also Considered the Youngsters

- BIRTHDAY PARTIES - 2019-2020 GOODBYE TO ALL THE BOTHER. SPORT VILLAGE WILL TAKE CARE OF EVERYTHING ! ACADEMIES Invitation cards provided Entertainment by qualified, dynamic monitors Cake, drinks and a bag of sweets for each child FROM 16 SEPTEMBER 2019 TO 14 JUNE 2020 LITTLE ATHLETES For children from 3 to 6 years old. GOLF Sports activities adapted for the smallest children: psychomotricity, mini-sports, parachute, musical awakening …. JUDO TREASURE HUNT For children from 3 to 8 years old. Team games, relay courses, adventure trails, treasure hunt…. DANCE MULTI-SPORTS For children from 7 to 12 years old. TENNIS Sports activities of choice: basketball, kin-ball, badminton, tennis, water games, frisbee, rugby, uni-hoc…. SWIMMING PAINTBALL* For children from 8 to 12 years old. Equipment adapted to the children CAPOEIRA and their size. They will have light launchers that work without compressed air. MINI-FOOTBALL A LA CARTE For children from 3 to 12 years old. Inflatable castles, clown, magician, cuistax, make-up…. TRIATHLON As a supplement to the classic formula. KRAV MAGA SATURDAYS AND SUNDAYS From 2pm to 4.30pm: €200 for 10 children + €20/extra child TAEKWONDO From 2pm to 5.30pm: €250 for 10 children + €25/extra child *Paintball ROLLER SKATING HOCKEY From 2pm to 4.30pm: €300 for 10 children + €25/extra child From 2pm to 5.30pm: €350 for 10 children + €30/extra child ARTISTIC ROLLER SKATING INFORMATION & RESERVATIONS 02/633.61.50 - [email protected] WWW.SPORTVILLAGE.BE 117, Vieux Chemin de Wavre - 1380 Lasne - 02/633.61.50 - [email protected] - 2019-2020 ACADEMIES - - TRIATHLON - INTRODUCTION Because sport is a family affair, Sport Village has also considered the youngsters. -

Sport England Annual Report 2004-2005

Presented pursuant to section 33(1) and section 33(2) of the National Lottery etc. Act 1993 (as amended by the National Lottery Act 1998) Sport England Annual Report and Accounts 2004-2005 ORDERED BY THE HOUSE OF COMMONS TO BE PRINTED 19 January 2006 LAID BEFORE THE PARLIAMENT BY THE MINISTERS 19 January 2006 LONDON: The Stationery Office 19 January 2006 HC 302 £ Contents 2004-05 Annual report against DCMS-Sport Page 3 England funding agreement 2003-06 Sport England - Summary of Lottery Awards 2004-05 Page 12 Sport England Lottery Awards 2004-05 - Awards over £100,000 Page 14 Ongoing awards over £5 million and their status Page 19 Sport England - Lottery Accounts Page 20 Performance Indicators 2004-05 Sport England Lottery Fund Monitoring & Evaluation Page 21 Financial directions issued under sections 26 (3), (3A) and (4) Page 24 of The National Lottery Etc. Act 1993 (as amended by The National Lottery Act 1998) Policy Directions Issued under Section 26 of the National Page 28 Lottery etc Act 1993 amended 1998 The English Sports Council National Lottery Distribution Page 31 Account for the year ended 31 March 2005 The Space for Sport and Arts Programme Memorandum Page 64 Accounts for the year ended 31 March 2005 The English Sports Council and English Sports Council Group Page 69 Consolidated Accounts for the year ended 31 March 2005 2 2004-05 ANNUAL REPORT AGAINST DCMS-SPORT ENGLAND FUNDING AGREEMENT 2003-06 2004-05: Another year of progress and achievement Work area 04/05: Key achievements Strategic Leadership Sport England celebrates -

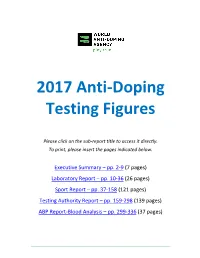

2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Report

2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Please click on the sub‐report title to access it directly. To print, please insert the pages indicated below. Executive Summary – pp. 2‐9 (7 pages) Laboratory Report – pp. 10‐36 (26 pages) Sport Report – pp. 37‐158 (121 pages) Testing Authority Report – pp. 159‐298 (139 pages) ABP Report‐Blood Analysis – pp. 299‐336 (37 pages) ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Executive Summary ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Samples Analyzed and Reported by Accredited Laboratories in ADAMS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Executive Summary is intended to assist stakeholders in navigating the data outlined within the 2017 Anti -Doping Testing Figures Report (2017 Report) and to highlight overall trends. The 2017 Report summarizes the results of all the samples WADA-accredited laboratories analyzed and reported into WADA’s Anti-Doping Administration and Management System (ADAMS) in 2017. This is the third set of global testing results since the revised World Anti-Doping Code (Code) came into effect in January 2015. The 2017 Report – which includes this Executive Summary and sub-reports by Laboratory , Sport, Testing Authority (TA) and Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) Blood Analysis – includes in- and out-of-competition urine samples; blood and ABP blood data; and, the resulting Adverse Analytical Findings (AAFs) and Atypical Findings (ATFs). REPORT HIGHLIGHTS • A analyzed: 300,565 in 2016 to 322,050 in 2017. 7.1 % increase in the overall number of samples • A de crease in the number of AAFs: 1.60% in 2016 (4,822 AAFs from 300,565 samples) to 1.43% in 2017 (4,596 AAFs from 322,050 samples). -

To View the 2016 World Bowls Championships Media

2016 WORLD BOWLS CHAMPIONSHIPS MEDIA KIT (613) 244-0021 (613) 244-0041 [email protected] Web: www.bowlscanada.com Bowls Canada Boulingrin 33 Roydon Place, Suite 206 Nepean, Ontario K2E 1A3 Play Begins at World Bowls Championships Team Canada is ready for action at the 2016 World Bowls Championships. After a week of acclimatization and training, our athletes are ready to put their best bowl forward and take on the top bowlers in the world. Week one will feature the women playing singles and fours, while the men play pairs and triples. Kelly McKerihen (Toronto, ON) will represent Canada in the singles and after months of showing great success on the greens in the Southern Hemisphere, McKerihen is ready to compete. The women’s fours team represents a powerhouse of international experience with Leanne Chinery (Victoria, BC), Shirley Fitzpatrick-Wong (Winnipeg, MB) and Jackie Foster (Lower Sackville, NS). Rookie lead Pricilla Westlake (Delta, BC) may be new to international team play at this level, but the team is looking to capitalize on her recent successes at the 2016 World Indoor Cup and North American Challenge. “Even though New Zealand is now my home, I will always be a proud Canadian. I consider it a great honour to be able to wear the Maple Leaf and represent Canada to the best of my abilities” stated Chinery. On the men’s side, Ryan Bester (Hanover, ON) and Steven Santana (North Vancouver, BC) will be a heavy favourite in the pairs. These two are looking to continue the momentum from their gold medal win at the 2015 Asia Pacific Championships.