IMPORTANCE of MYANMAR in CHINA's STRATEGIC INTEREST: a CASE STUDY on SINO-MYANMAR OIL and GAS PIPELINES Dissertation Submitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overview of the Myanmar-China Oil & Gas Pipelines

Caring for Energy·Caring for You Overview of the Myanmar-China Oil & Gas Pipelines The Myanmar-China Oil & Gas Pipelines is an international cooperation project. The Myanmar-China Crude Oil Pipeline is jointly invested and constructed by SEAP and MOGE; their joint venture, South-East Asia Crude Oil Pipeline Company Limited (SEAOP), is responsible for its operation and management. While the Myanmar-China Gas Pipeline Project is jointly invested and constructed by SEAP, MOGE, POSCO DAEWOO, ONGC CASPIAN E&P B.V., GAIL and KOGAS; their joint venture, South-East Asia Gas Pipeline Company Limited (SEAGP), is responsible for its operation and management. Both joint ventures have adopted the General Meeting of Shareholders/Board of Directors for regulation and decision-making on major issues. Operational and management structure of JV companies of the Myanmar-China Oil & Gas Pipeline Project CNPC SEAP MOGE CNPC SEAP MOGE POSCO DAEWOO OCEBV GAIL KOGAS South-East Asia Crude Oil South-East Asia Gas Pipeline Pipeline Company Limited Company Limited Shareholders/ Shareholders/ Board of Directors Board of Directors 300,000-ton crude oil terminal on Madè Island 08 Myanmar-China Oil & Gas Pipeline Project (Myanmar Section) Special Report on Social Responsibility Myanmar-China Crude Oil Pipeline Myanmar-China Gas Pipeline The 771-kilometer long pipeline extends from Madè Island The Myanmar-China Gas Pipeline starts at Ramree Island on on the west coast of Myanmar to Ruili in the southwestern the western coast of Myanmar and ends at Ruili in China’s Chinese province of Yunnan, running through Rakhine Yunnan Province. Running in parallel with the Myanmar-China State, Magwe Region, Mandalay Region, and Shan State. -

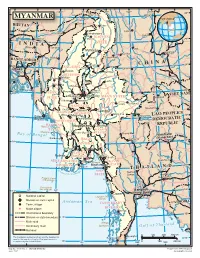

Map of Myanmar

94 96 98 J 100 102 ° ° Indian ° i ° ° 28 n ° Line s Xichang Chinese h a MYANMAR Line J MYANMAR i a n Tinsukia g BHUTAN Putao Lijiang aputra Jorhat Shingbwiyang M hm e ra k Dukou B KACHIN o Guwahati Makaw n 26 26 g ° ° INDIA STATE n Shillong Lumding i w d Dali in Myitkyina h Kunming C Baoshan BANGLADE Imphal Hopin Tengchong SH INA Bhamo C H 24° 24° SAGAING Dhaka Katha Lincang Mawlaik L Namhkam a n DIVISION c Y a uan Gejiu Kalemya n (R Falam g ed I ) Barisal r ( r Lashio M a S e w k a o a Hakha l n Shwebo w d g d e ) Chittagong y e n 22° 22° CHIN Monywa Maymyo Jinghong Sagaing Mandalay VIET NAM STATE SHAN STATE Pongsali Pakokku Myingyan Ta-kaw- Kengtung MANDALAY Muang Xai Chauk Meiktila MAGWAY Taunggyi DIVISION Möng-Pan PEOPLE'S Minbu Magway Houayxay LAO 20° 20° Sittwe (Akyab) Taungdwingyi DEMOCRATIC DIVISION y d EPUBLIC RAKHINE d R Ramree I. a Naypyitaw Loikaw w a KAYAH STATE r r Cheduba I. I Prome (Pye) STATE e Bay Chiang Mai M kong of Bengal Vientiane Sandoway (Viangchan) BAGO Lampang 18 18° ° DIVISION M a e Henzada N Bago a m YANGON P i f n n o aThaton Pathein g DIVISION f b l a u t Pa-an r G a A M Khon Kaen YEYARWARDY YangonBilugyin I. KAYIN ATE 16 16 DIVISION Mawlamyine ST ° ° Pyapon Amherst AND M THAIL o ut dy MON hs o wad Nakhon f the Irra STATE Sawan Nakhon Preparis Island Ratchasima (MYANMAR) Ye Coco Islands 92 (MYANMAR) 94 Bangkok 14° 14° ° ° Dawei (Krung Thep) National capital Launglon Bok Islands Division or state capital Andaman Sea CAMBODIA Town, village TANINTHARYI Major airport DIVISION Mergui International boundary 12° Division or state boundary 12° Main road Mergui n d Secondary road Archipelago G u l f o f T h a i l a Railroad 0 100 200 300 km Chumphon The boundaries and names shown and the designations Kawthuang 10 used on this map do not imply official endorsement or ° acceptance by the United Nations. -

How/In What Way Will the Strategic Situation in Southeast Asia Be Challenged by Building of Chinese Ports and Naval Bases in Burma/Myanmar?

How/in what way will the strategic situation in Southeast Asia be challenged by building of Chinese ports and naval bases in Burma/Myanmar? Marie Brødholt Master Thesis East Asian Studies University of Oslo Spring 2011 1 Acknowledgements I would like to direct my thanks to ...... ...... my supervisor, Vladimir Tikhonov, for advice and extreme patience. ...... the National Theatre of Norway and the people working there for letting me write my thesis in this extraordinary building and environment (as someone would not let me have a place of my own at the University). ...... my friends and co-workers for support and for telling me how smart I am (when I know they are lying). ...... my sister and brother-in-law for support, dinners, and WII-intervals, and to my sister for trying to correct my bad grammar and spelling (she did not have the opportunity to read this page, so these are all my own errors). ...... my parents for encouragements, for tolerating mountains of books in their living room when I am visiting, suffering through my complaints on everything, and transportation. 2 Summary China is going through extraordinary economical growth. China’s leaders must balance growing energy demands with the ability to guarantee security in the shipping lanes. Most of the oil Chinese industry depends on comes from Africa and the Middle East. The fastest route from Africa and the Middle East to China is through the Straits of Malacca. The Straits of Malacca are the most trafficked sea route in Asia and one of the most important shipping lanes in the world. -

BURMA) H a Ratchasima O P Nam Tok H R COCO ISLANDS MOSCOS a Dawei Y

S 90 96 a 102 l Hexi Gyigang w CHINA e e n Dong Xichang Murkong e tz g Thimphu Selek n + Y a NEP. Tinsukia a Y n a Putao Zhaotong D¯arjiling tr g BHUTAN u t p z It¯anagar a Ledo e m Brah Shingbwiyang Dayan Panzhihua Jorh¯at (Ligiang) Guw¯ah¯ati Tangdan INDIA in w d in Rangpur Shillong h CHINA R¯aiganj Lumding u/c Dali t C Qujing ra¯ Myitkyina a B M Baoshan e Kunming k G o a n R n Sylhet Imphal g e Chuxiong g g d an e c Ji s u/ Xi R¯ajsh¯ahi B Mengmao Fengshan la c BANGLADESH Bhamo (Ruili) (Fengqing) k 24 y 24 d Dhaka d Baoxiu a Aizwal a n Kaiyuan P h w a g a d r m e a r Mawlaik I M INDIA Kalemyo Mogok Simao Lashio Khulna Shwebo Kolkata Hakha Lào Cai R (Calcutta) Chittagong Monywa Lai Châu ed Maymyo VIETNAM es Sagaing Mandalay e Gang Mouths of th Phôngsali B Pakokku la Cox’s B¯az¯ar Myingyan Lawksawk Son La ck Keng Chauk Loi-lem Tung Louang Meiktila Taunggyi Namtha Xam Nua Nay Pyi Taw een g Akyab Magway (administrative Salw kon Louangphrabang capital) Me Loikaw Chiang Pyinmana Rai LAOS Kyaukpyu Thayetmyo m Ramree Island o Y Xiangkhoang Prome Mae Hong Ramree Song Chiang m (Pyay) a Taungoo N Munaung Ir S Mai Nan ra it e t a Island w a n M Vientiane a g 18 d Lampang d M 18 y e Nyaunglebin ko Hinthada Loei ng Bay Bago Udon Thani of Thaton Phitsanulok Pathein Hpa-an Tak M Khon ae N Kaen Rangoon a Phetchabun Bengal m Lam Nam Mawlamyine Mudon P C in h i Pyapon g y d d a THAILAND w Mou Irra ths of the M Nakhon a e Sawan Ye N a m Preparis Island C Nakhon (BURMA) h a Ratchasima o P Nam Tok h r COCO ISLANDS MOSCOS a Dawei y (BURMA) a Bangkok ( ( -

177 China's Myanmar Dilemma

CHINA’S MYANMAR DILEMMA Asia Report N°177 – 14 September 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. BEIJING NAVIGATES MYANMAR’S POLITICS ..................................................... 2 A. BILATERAL RELATIONS ...............................................................................................................2 B. UNITED NATIONS.........................................................................................................................4 1. The Security Council veto ...........................................................................................................4 2. Beijing’s reaction to the Saffron Revolution ...............................................................................6 3. Ensuring aid after Cyclone Nargis...............................................................................................8 4. Detention and trial of Aung San Suu Kyi ....................................................................................9 C. CHINA AND THE OPPOSITION........................................................................................................9 D. CHINA AND THE ETHNIC GROUPS...............................................................................................10 III. DRIVERS OF CHINESE POLICY.............................................................................. -

Broken Ethics

BROKEN ETHICS The Norwegian Government’s Investments in Oil and Gas Companies Operating in Burma (Myanmar) A Report by EarthRights International, December 2010 Research, Writing, and Production Team Matthew Smith, Naing Htoo, Zaw Zaw, Shauna Curphey, Paul Donowitz, Brad Weikel, Ross Dana Flynn, and Anonymous Field Teams. About EarthRights International (ERI) EarthRights International is a nongovernmental, nonprofit organization that combines the power of law and the power of people in defense of human rights and the environment, which we define as “earth rights.” We specialize in fact-finding, legal actions against perpetrators of earth rights abuses, training grassroots and community leaders, and advocacy campaigns. Through these strategies, ERI seeks to end earth rights abuses, to provide real solutions for real people, and to promote and protect human rights and the environment in the communities where we work. Acknowledgments EarthRights International would like to thank the generous individual and institutional supporters who make our work possible. Special thanks to Stephen Cha-Kim, Tasneem Clarke, Jared Magnuson, Alek Nomi, and the entire staff of EarthRights International for their direct and indirect assistance in preparing this report. Thanks also to the board of directors of EarthRights International for their support and direction. We could not do our work without the partnership and strategic collaboration of the many NGOs and civil society organizations working for human rights and environmental protection in Burma. We thank all of you. Most importantly, EarthRights International acknowledges the people of Burma. Many individuals from the country took great risks to offer their testimony or provide insight into Burma’s oil and gas sector, for no reward other than participating in the truth-telling process. -

Scanned Image

UNOPS eSourcing v2017.1 Section II: Schedule of Requirements eSourcing reference: RFQ/2020/15086 Terms of Reference Foundation Investigation for health facilities in Hlaing Thar Yar Township in Yangon Region of Myanmar 1.0 SCOPE The works for soil investigation shall be carried out in accordance with the specification set out below and as directed by the UNOPS, wherever necessary. The main scope of the work shall include but not limited to the following: ● Performing Site-Specific Ground Motion Study for Seismic Design of Building, ● Soil Liquefaction assessment during Seismic events and foundation recommendations to mitigate liquefaction effects The detail scope is indicated in the section 2.2- reporting below. The scope of the work conform to the relevant Standards on Soils and Foundations for field investigations and Laboratory testing. Reference to any code in these TOR shall mean the latest revision of the code unless otherwise mentioned. In the event of any conflict between the requirements in these TOR and the referred codes, the former shall govern. 2.0 TECHNICAL REQUIREMENTS 2.1 GENERAL The purpose of the proposed sub-soil investigation is to provide adequate information on sub-surface and surface conditions for the foundations and other sub-structures for the proposed project, with special attention to the analysis of liquefied soils, leading to safe foundation design and site specific ground motion study for determining spectral parameters for design of superstructure. The planning of the work, choice of the method of boring, -

THE STATE of LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS in YANGON Photo Credits

Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN YANGON Photo credits Yangon Heritage Trust Thomas Schaffner (bottom photo on cover and left of executive summary) Gerhard van ‘t Land Susanne Kempel Myanmar Survey Research The views expressed in this publication are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of UNDP. Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN YANGON UNDP MYANMAR Table of Contents Acknowledgements II Acronyms III Executive Summary 1 - 4 1. Introduction to the Local Governance Mapping 5 - 8 1.1 Yangon Region - most striking features 7 1.2 Yangon City Development Committee and the Region government 8 1.3 Objectives of the report and its structure 8 2. Descriptive overview of governance structures in Yangon Region 9 - 38 2.1 Yangon Region - administrative division 11 2.2 Yangon Region - Socio-economic and historical context 13 2.3 Yangon City Development Committee (YCDC) 18 2.4 Yangon Region Government 24 2.5 Representation of Yangon Region in the Union Hluttaws 33 2.6 Some of the governance issues that Yangon Region and YCDC are facing 37 3. Organisation of service delivery at the township level 39 - 62 3.1 Governance structures at the township level 43 3.2 Planning and Budgeting 46 3.3 Role of GAD and the VTAs/WAs 48 3.4 The TDSC and the TMAC 51 3.5 Election and selection processes for peoples’ representatives 53 3.6 Three concrete services - people’s participation and providers views 54 3.7 Major development issues from a service provider perspective 60 4. -

Flash Alert – Covid-19 Pandemic in Myanmar: Details on 29 September Cases Wednesday, September 30, 2020

Flash alert – Covid-19 Pandemic in Myanmar: Details on 29 September Cases Wednesday, September 30, 2020 Yesterday evening at 20:00 hrs, 7971 new Covid-19 cases were identified, i.e. 12,053 cases since the beginning of the second wave on 16 August. Since the beginning of the pandemic in March, 12,427 people have been contaminated in Myanmar, and a total of 284 people have died of Covid-19. At 16:30 Hrs, the MoHS released the spatial breakdown of those 797 cases: 661 in Yangon Region, 32 in Mandalay Region, 24 Kachin State, 23 in Rakhine State, 16 in Ayeyarwaddy Region, 15 in Bago Region, 11 in Mon State, 7 in Magway Region, 3 in Tanintharyi Region, 2 in Kayin State, 2 in Naypyitaw Territory of Union and 1 in Shan State. Since 16 August, 8,979 cases have been reported in Yangon Region. Yesterday, the most significant surges took place in Insein Township (+108 cases), Shwepyithar Township (+51) and Twantay Township (+49). Insein is the most-affected township in Yangon, ahead of Thingangyun, South and North Okkalapa, Tarmwe, Hlaing, Hlaing Thayar, Thaketa and Mingaladon Townships. Imported cases N° of new cases on 29 N° of total cases Township Local cases from abroad September since 16 August Ahlone 6 121 Bahan 15 193 Botahtaung 1 126 Dagon 4 182 Dagon Myothit (East) 28 180 Dagon Myothit (North) 4 184 Dagon Myothit (South) 10 199 Dagon Seikkan 6 97 Dala 5 286 1 The announcement originally mentioned 795 cases, but two additional cases were added after the details were released. -

Hazard Profile of Myanmar: an Introduction 1.1

Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................ I List of Figures ................................................................................................................ III List of Tables ................................................................................................................. IV Acronyms and Abbreviations ......................................................................................... V 1. Hazard Profile of Myanmar: An Introduction 1.1. Background ...................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Myanmar Overview ......................................................................................................... 2 1.3. Development of Hazard Profile of Myanmar : Process ................................................... 2 1.4. Objectives and scope ....................................................................................................... 3 1.5. Structure of ‘Hazard Profile of Myanmar’ Report ........................................................... 3 1.6. Limitations ....................................................................................................................... 4 2. Cyclones 2.1. Causes and Characteristics of Cyclones in the Bay of Bengal .......................................... 5 2.2. Frequency and Impact .................................................................................................... -

Doing Business in Myanmar

www.pwc.com/mm Doing business in Myanmar Fourth edition May 2016 Table of Contents 1. Foreword 4 2. The economy 8 2.1 Economic prospects 10 2.2 Regulatory environment surrounding foreign investment 11 2.3 Major foreign investors in Myanmar 12 2.4 Key sectors for foreign investment 13 2.5 Domestic investments 14 2.6 Major deals in Myanmar 16 2.7 Special Economic Zones 21 3. Myanmar infrastructure 22 3.1 Myanmar key infrastructure insights 22 3.2 Myanmar power sector 24 3.3 Transport sector 26 3.4 Telecom sector 31 3.5 Healthcare sector 33 3.6 Urbanisation 35 3.7 Special economic zones 37 3.8 Conclusion 39 4. Myanmar financial sector 41 4.1 Recent developments in the Myanmar financial sector 41 4.2 Listing of banks 46 4.3 Other non-bank finanical institutes 50 4.4 Insurance sector 52 4.5 Other useful information 54 5. Taxation in Myanmar 55 5.1 Corporate income tax 55 5.2 Personal income tax 61 5.3 Commercial tax 63 5.4 Other taxes 64 2 PwC 6. Human resources and employment law 66 6.1 Employment of foreigners 66 6.2 Work permit processing and requirements 67 (Managerial, supervisor, expertise) 6.3 Labour Laws in Myanmar 67 6.4 Permanent residency in Myanmar 67 7. Other considerations 68 7.1 Commercial registration and licensing requirements 68 7.2 Exchange control 69 7.3 Foreign exchange 69 7.4 Foreign ownership of land and property 70 7.5 Arbitration law 71 7.6 Economic and trade 71 8. -

Burma 2015 Human Rights Report

BURMA 2015 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Burma has a quasi-parliamentary system of government in which national parliament selects the president and constitutional provisions grant one-quarter of national, regional, and state parliamentary seats to active-duty military appointees. The military also has the authority to appoint the ministers of defense, home affairs, and border affairs and indefinitely assume power over all branches of the government should the president declare a national state of emergency. On November 8, the country held nationwide parliamentary elections that the public widely accepted as a credible reflection of the will of the people, despite some structural flaws. The opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) party, chaired by Aung San Suu Kyi, won 390 of 491 contested seats in the bicameral parliament. Civilian authorities did not maintain effective control over the security forces. The three leading human rights problems in the country were restrictions on freedoms of speech, association, and assembly; human rights violations in ethnic minority areas affected by conflict; and restrictions on members of the Rohingya population. Arrests of students, land rights activists, and individuals in connection with the exercise of free speech and assembly continued throughout the year, and the excessive sentencing of many of these individuals after prolonged trial diminished trust in the judicial system. Mass displacement and gross human rights abuses took place in ethnic areas with renewed clashes, and the government took marginal steps to address reports of abuses. The government did little to address the root causes of human rights abuses, statelessness, violence, and discrimination against Rohingya.