Myanmar in Transition Opportunities and Challenges Myanmar in Transition Opportunities and Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rakhine State

Myanmar Information Management Unit Township Map - Rakhine State 92° E 93° E 94° E Tilin 95° E Township Myaing Yesagyo Pauk Township Township Bhutan Bangladesh Kyaukhtu !( Matupi Mindat Mindat Township India China Township Pakokku Paletwa Bangladesh Pakokku Taungtha Samee Ü Township Township !( Pauk Township Vietnam Taungpyoletwea Kanpetlet Nyaung-U !( Paletwa Saw Township Saw Township Ngathayouk !( Bagan Laos Maungdaw !( Buthidaung Seikphyu Township CHIN Township Township Nyaung-U Township Kanpetlet 21° N 21° Township MANDALAYThailand N 21° Kyauktaw Seikphyu Chauk Township Buthidaung Kyauktaw KyaukpadaungCambodia Maungdaw Chauk Township Kyaukpadaung Salin Township Mrauk-U Township Township Mrauk-U Salin Rathedaung Ponnagyun Township Township Minbya Rathedaung Sidoktaya Township Township Yenangyaung Yenangyaung Sidoktaya Township Minbya Pwintbyu Pwintbyu Ponnagyun Township Pauktaw MAGWAY Township Saku Sittwe !( Pauktaw Township Minbu Sittwe Magway Magway .! .! Township Ngape Myebon Myebon Township Minbu Township 20° N 20° Minhla N 20° Ngape Township Ann Township Ann Minhla RAKHINE Township Sinbaungwe Township Kyaukpyu Mindon Township Thayet Township Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Mindon Township !( Bay of Bengal Ramree Kamma Township Kamma Ramree Toungup Township Township 19° N 19° N 19° Munaung Toungup Munaung Township BAGO Padaung Township Thandwe Thandwe Township Kyangin Township Myanaung Township Kyeintali !( 18° N 18° N 18° Legend ^(!_ Capital Ingapu .! State Capital Township Main Town Map ID : MIMU1264v02 Gwa !( Other Town Completion Date : 2 November 2016.A1 Township Projection/Datum : Geographic/WGS84 Major Road Data Sources :MIMU Base Map : MIMU Lemyethna Secondary Road Gwa Township Boundaries : MIMU/WFP Railroad Place Name : Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) translated by MIMU AYEYARWADY Coast Map produced by the MIMU - [email protected] Township Boundary www.themimu.info Copyright © Myanmar Information Management Unit Yegyi Ngathaingchaung !( State/Region Boundary 2016. -

Pangolin Trade in the Mong La Wildlife Market and the Role of Myanmar in the Smuggling of Pangolins Into China

Global Ecology and Conservation 5 (2016) 118–126 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Global Ecology and Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gecco Original research article Pangolin trade in the Mong La wildlife market and the role of Myanmar in the smuggling of pangolins into China Vincent Nijman a, Ming Xia Zhang b, Chris R. Shepherd c,∗ a Oxford Wildlife Trade Research Group, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK b Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Gardens, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Mengla, China c TRAFFIC, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia article info a b s t r a c t Article history: We report on the illegal trade in live pangolins, their meat, and their scales in the Special Received 7 November 2015 Development Zone of Mong La, Shan State, Myanmar, on the border with China, and Received in revised form 18 December 2015 present an analysis of the role of Myanmar in the trade of pangolins into China. Mong Accepted 18 December 2015 La caters exclusively for the Chinese market and is best described as a Chinese enclave in Myanmar. We surveyed the morning market, wildlife trophy shops and wild meat restaurants during four visits in 2006, 2009, 2013–2014, and 2015. We observed 42 bags Keywords: of scales, 32 whole skins, 16 foetuses or pangolin parts in wine, and 27 whole pangolins for Burma CITES sale. Our observations suggest Mong La has emerged as a significant hub of the pangolin Conservation trade. The origin of the pangolins is unclear but it seems to comprise a mixture of pangolins Manis from Myanmar and neighbouring countries, and potentially African countries. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

UNDERCURRENTS Monitoring Development on Burma’S Mekong

UNDERCURRENTS Monitoring Development on Burma’s Mekong INSIDE: Blasting the Mekong Consequences of the Navigation Scheme Road Construction in Shan State: Turning Illegal Drug Profits into Legal Revenues Sold Down the River The tragedy of human trafficking on the Mekong No Place Left for the Spirits of the Yellow Leaves Intensive logging leaves few options for the Mabri people in Shan State ...and more The Lahu National Development January 2005 Organization (LNDO) The Mekong/ Lancang The Mekong River is Southeast Asia’s longest, stretching from its source in Tibet to the delta of Vietnam. Millions of people depend on it for agriculture and fishing, and accordingly it holds a special cultural significance. For 234 kilometers, the Mekong forms the border between Burma’s Shan State and Luang Nam Tha and Bokeo provinces of Laos. This stretch includes the infamous “Golden Triangle”, or where Burma, Laos and Thailand meet, which has been known for illicit drug production. Over 22,000 primarily indigenous peoples live in the mountainous region of this isolated stretch of the river in Burma. The main ethnic groups are Akha, Shan, Lahu, Sam Tao (Loi La), Chinese, and En. The Mekong River has a special significance for the Lahu people. Like the Chinese, we call it the Lancang, and according to legends, the first Lahu people came from the river’s source. Traditional songs and sayings are filled with references to the river. True love is described as stretching form the source of the Mekong to the sea. The beauty of a woman is likened to the glittering scales of a fish in the Mekong. -

Mong La: Business As Usual in the China-Myanmar Borderlands

Mong La: Business as Usual in the China-Myanmar Borderlands Alessandro Rippa, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich Martin Saxer, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich The aim of this project is to lay the conceptual groundwork for a new understanding of the positionality of remote areas around the globe. It rests on the hypothesis that remoteness and connectivity are not independent features but co-constitute each other in particular ways. In the context of this project, Rippa and Saxer conducted exploratory fieldwork together in 2015 along the China-Myanmar border. This collaborative photo essay is one result of their research. They aim to convey an image of Mong La that goes beyond its usual depiction as a place of vice and unruliness, presenting it, instead, as the outcome of a particular China-inspired vision of development. Infamous Mong La It is 6:00 P.M. at the main market of Mong La, the largest town in the small autonomous strip of land on the Chinese border formally known in Myanmar as Special Region 4. A gambler from China’s northern Heilongjiang Province just woke up from a nap. “I’ve been gambling all morning,” he says, “but after a few hours it is better to stop. To rest your brain.” He will go back to the casino after dinner, as he did for the entire month he spent in Mong La. Like him, hundreds of gamblers crowd the market, where open-air restaurants offer food from all over China. A small section of the market is dedicated to Mong La’s most infamous commodity— wildlife. -

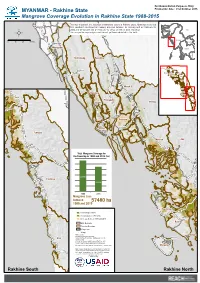

Mangrove Coverage Evolution in Rakhine State 1988-2015

For Humanitarian Purposes Only MYANMAR - Rakhine State Production date : 21st October 2015 Mangrove Coverage Evolution in Rakhine State 1988-2015 This map illustrates the evolution of mangrove extent in Rakhine State, Myanmar as derived Bhutan from Landsat-5 multispectral imagery acquired between 13 January and 23 February for Nepal Mindat 1988 and 30 January and 24 February for 2015 at 30m of pixel resolution. India China Town Bangladesh Bangladesh This is a preliminary analysis and has not yet been validated in the field. Paletwa Town Viet Nam Myanmar 0 10 20 30 Kms Laos Taungpyoletwea Kanpetlet Town Town Maungdaw Thailand Buthidaung Kyauktaw Cambodia Taungpyoletwea Maungdaw Kyauktaw Buthidaung Town Buthidaung Kyauktaw Maungdaw Kyauktaw Buthidaung Mrauk-U Town Maungdaw Rathedaung Mrauk-U Ponnagyun Town Minbya Rathedaung Ponnagyun Pauktaw Minbya Sittwe Pauktaw Myebon Sittwe Myebon Ann Ann Mrauk-U Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Kyaukpyu Ramree Ramree Toungup Rathedaung Mrauk-U Munaung Munaung Toungup Town Ann Thandwe Ponnagyun Thandwe Rathedaung Minbya Kyeintali Mindon Ma-Ei Town Town Town Gwa Gwa Ramree Minbya Town Ponnagyun Town Pauktaw Sittwe Pauktaw Town Sittwe Toungup Town Myebon Town Myebon Ann Toungup Town Total Mangrove Coverage for the Township in 1988 and 2015 (ha) Ann Town Thandwe Town 280986 Thandwe 223506 Kyaukpyu 1988 2015 Town Mangrove Loss between 57480 ha 1988 and 2015 Kyaukpyu New Mangrove area Kyeintali Town Remaining area 1988-2015 Ramree Decrease between 1988 and 2015 Town Ramree State Boundary Township Boundary Village-Tract Village Data sources: Toungup Landcover Analysis: UNOSAT Administrative Boundaries, Settlements: OCHA Munaung Gwa Town Roads: OSM Coordinate System: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 46N Contact: [email protected] File: REACH_MMR_Map_Rakhine_HVA_Mangrove_21OCT2015_A1 Munaung Note: Data, designations and boundaries contained Gwa Town on this map are not warranted to be error-free and do not imply acceptance by the REACH partners, associated, donors mentioned on this map. -

139416 Rakhine State

Rakhine State (Myanmar) as of 22 May 2013 Total Estimated IDP Population 139,416 Total Number of Households 22,773 Rakhine Situation Overview Inter-community conflict in Rakhine State, which erupted in early June 2012 and resurfaced in October 2012, has resulted in displacement and loss of lives and livelihoods. As of beginning of April 2013, the number of people displaced in Rakhine State has surpassed 139,000, of whom about 75,000 displaced since June 2012 and the remaining following Kyauktaw October. Many others continue living in tents close to their places of origin while their houses are being rebuilt, or with Maungdaw 6418 host families. The IDP population is currently hosted in 76 camps and camp-like settings. The Shelter/NFI/CCCM Cluster 3569 was activated in December 2012 in Yangon. Only more recently (middle March 2013) did the CCCM Cluster become Mrauk-U operational in Rakhine State. Therefore the sectoral response is still at a very early stage at field level. Rathedaung 4135 4008 Minbya Number of IDP sites by township IDP population by township 5152 as of 22 May 2013 as of 22 May 2013 Sittwe Pauktaw Minbya 8 Minbya 5,152 19976 Meybon Mrauk-U 4 Mrauk-U 4,135 89880 4169 Meybon 2 Meybon 4,169 Pauktaw 6 Pauktaw 19,976 Kyauktaw 11 Kyauktaw 6,418 Rathedaung 4 Rathedaung 4,008 Kyauk Phyu 2 Kyauk Phyu 1,849 Kyauk Phyu Ramree 2 Rakhine Ramree 260 1849 Sittwe 23 Sittwe 89,880 Maungdaw 14 Maungdaw 3,569 Type of accomodation at IDP sites Ramree Number of IDP sites IDP population by type of 260 'Planned / Managed Camp' purpose-built sites by type of accommodation accommodation where services and infrastructure is provided 139,416IDPs including water supply, food distribution, non- food item, education, and health care, usually targeted by humanitarian partners exclusively for the population of the site. -

Rakhine State, Myanmar

World Food Programme S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 Photographs: ©FAO/F. Del Re/L. Castaldi and ©WFP/K. Swe. This report has been prepared by Monika Tothova and Luigi Castaldi (FAO) and Yvonne Forsen, Marco Principi and Sasha Guyetsky (WFP) under the responsibility of the FAO and WFP secretariats with information from official and other sources. Since conditions may change rapidly, please contact the undersigned for further information if required. Mario Zappacosta Siemon Hollema Senior Economist, EST-GIEWS Senior Programme Policy Officer Trade and Markets Division, FAO Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific, WFP E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org at the following URL address: http://www.fao.org/giews/ The Global Information and Early Warning System on Food and Agriculture (GIEWS) has set up a mailing list to disseminate its reports. To subscribe, submit the Registration Form on the following link: http://newsletters.fao.org/k/Fao/trade_and_markets_english_giews_world S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Rome, 2019 Required citation: FAO. -

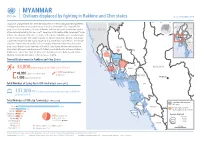

MYANMAR Civilians Displaced by fighting in Rakhine and Chin States As of 1 December 2019

MYANMAR Civilians displaced by fighting in Rakhine and Chin states As of 1 December 2019 Thousands of people have been internally displaced since the escalation of fighting between INDIA the Myanmar Armed Forces and the Arakan Army (AA) in December 2018. Nearly 45,000 INDIA people have fled insecurity to 131 sites in Rakhine and Chin states with an unknown number BANGLADESH CHINA of people being hosted by families. As of 1 December 2019, Rakhine State Government figures indicate that about 43,000 people are displaced in 119 sites in Rakhine State and operational partners report around 1,800 displaced people are living in 12 sites in Chin State. Population Nay Pyi Taw movements remain fluid with regular reports of displacement and some returns. The number THAILAND of people displaced by this conflict increased sharply in November when more than 9,000 people were displaced in the townships of Mrauk-U, Rathedaung, Myebon and Buthidaung. PALETWA Intensified fighting and new displacements further complicate the humanitarian situation in BUTHIDAUNG CHIN Rakhine State where more than 131,000 people, including stateless Rohingya and Kaman MANDALAY Muslims, remain displaced since sectarian violence in 2012. MAUNGDAW Recent Displacement in Rakhine and Chin States KYAUKTAW PONNAGYUN MAGWAY people displaced by conflict as of 1 Dec’19 MINBYA 44,800 MRAUK-U RATHEDAUNG + 9,000 newly displaced 43,000 displaced in Rakhine State in November RAKHINE SITTWE Magway 1,800 displaced in Chin State PAUKTAW Sittwe MYEBON Total Number of Long-Term IDPs in Camps -

Overview of the Myanmar-China Oil & Gas Pipelines

Caring for Energy·Caring for You Overview of the Myanmar-China Oil & Gas Pipelines The Myanmar-China Oil & Gas Pipelines is an international cooperation project. The Myanmar-China Crude Oil Pipeline is jointly invested and constructed by SEAP and MOGE; their joint venture, South-East Asia Crude Oil Pipeline Company Limited (SEAOP), is responsible for its operation and management. While the Myanmar-China Gas Pipeline Project is jointly invested and constructed by SEAP, MOGE, POSCO DAEWOO, ONGC CASPIAN E&P B.V., GAIL and KOGAS; their joint venture, South-East Asia Gas Pipeline Company Limited (SEAGP), is responsible for its operation and management. Both joint ventures have adopted the General Meeting of Shareholders/Board of Directors for regulation and decision-making on major issues. Operational and management structure of JV companies of the Myanmar-China Oil & Gas Pipeline Project CNPC SEAP MOGE CNPC SEAP MOGE POSCO DAEWOO OCEBV GAIL KOGAS South-East Asia Crude Oil South-East Asia Gas Pipeline Pipeline Company Limited Company Limited Shareholders/ Shareholders/ Board of Directors Board of Directors 300,000-ton crude oil terminal on Madè Island 08 Myanmar-China Oil & Gas Pipeline Project (Myanmar Section) Special Report on Social Responsibility Myanmar-China Crude Oil Pipeline Myanmar-China Gas Pipeline The 771-kilometer long pipeline extends from Madè Island The Myanmar-China Gas Pipeline starts at Ramree Island on on the west coast of Myanmar to Ruili in the southwestern the western coast of Myanmar and ends at Ruili in China’s Chinese province of Yunnan, running through Rakhine Yunnan Province. Running in parallel with the Myanmar-China State, Magwe Region, Mandalay Region, and Shan State. -

How/In What Way Will the Strategic Situation in Southeast Asia Be Challenged by Building of Chinese Ports and Naval Bases in Burma/Myanmar?

How/in what way will the strategic situation in Southeast Asia be challenged by building of Chinese ports and naval bases in Burma/Myanmar? Marie Brødholt Master Thesis East Asian Studies University of Oslo Spring 2011 1 Acknowledgements I would like to direct my thanks to ...... ...... my supervisor, Vladimir Tikhonov, for advice and extreme patience. ...... the National Theatre of Norway and the people working there for letting me write my thesis in this extraordinary building and environment (as someone would not let me have a place of my own at the University). ...... my friends and co-workers for support and for telling me how smart I am (when I know they are lying). ...... my sister and brother-in-law for support, dinners, and WII-intervals, and to my sister for trying to correct my bad grammar and spelling (she did not have the opportunity to read this page, so these are all my own errors). ...... my parents for encouragements, for tolerating mountains of books in their living room when I am visiting, suffering through my complaints on everything, and transportation. 2 Summary China is going through extraordinary economical growth. China’s leaders must balance growing energy demands with the ability to guarantee security in the shipping lanes. Most of the oil Chinese industry depends on comes from Africa and the Middle East. The fastest route from Africa and the Middle East to China is through the Straits of Malacca. The Straits of Malacca are the most trafficked sea route in Asia and one of the most important shipping lanes in the world. -

Fire and Ice: Conflict and Drugs in Myanmar’S Shan State

Fire and Ice: Conflict and Drugs in Myanmar’s Shan State Asia Report N°299 | 8 January 2019 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 149 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. A Long Legacy ................................................................................................................... 3 III. A New Drug Dynamic ....................................................................................................... 6 A. A Surge in Production ................................................................................................ 6 B. Tip of the Iceberg ....................................................................................................... 10 IV. The Links Between Drugs and Conflict ............................................................................ 12 A. Current Conflict Dynamics ........................................................................................ 12 B. The Role of the Drug Trade in the Conflict................................................................ 13 C. Ethno-political Clashes, Anti-drug Raids or Bank Heists? ....................................... 15 D. Why Is There Not