Pangolin Trade in the Mong La Wildlife Market and the Role of Myanmar in the Smuggling of Pangolins Into China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Illegal Wildlife Trade: Through the Eyes of a One-Year-Old Pangolin (Manis Javanica)

Animal Studies Journal Volume 9 Number 2 Article 6 2020 The Illegal Wildlife Trade: Through The Eyes of a One-Year-Old Pangolin (Manis javanica) Lelia Bridgeland-Stephens University of Birmingham, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/asj Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Creative Writing Commons, Criminology Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Other Animal Sciences Commons, and the Other Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Bridgeland-Stephens, Lelia, The Illegal Wildlife Trade: Through The Eyes of a One-Year-Old Pangolin (Manis javanica), Animal Studies Journal, 9(2), 2020, 111-146. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/asj/vol9/iss2/6 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The Illegal Wildlife Trade: Through The Eyes of a One-Year-Old Pangolin (Manis javanica) Abstract This paper explores the literature on the illegal wildlife trade (IWT) by following the journey of a single imagined Sunda pangolin (Manis javanica) through the entire trading process. Literature on IWT frequently refers to non-human animals in terms of collectives, species, or body parts, for example ‘tons of pangolin scales’, rather than as subjective individuals. In contrast, this paper centralizes the experiences of an individual pangolin by using a cross- disciplinary methodology, combining fact with a fictional narrative of subjective pangolin experience, in an empathetic and egomorphic process. The paper draws together known legislation, trade practices, and pangolin biology, structured around the journey of an imagined pangolin. -

PROCEEDINGS of the WORKSHOP on TRADE and CONSERVATION of PANGOLINS NATIVE to SOUTH and SOUTHEAST ASIA 30 June – 2 July 2008, Singapore Zoo Edited by S

PROCEEDINGS OF THE WORKSHOP ON TRADE AND CONSERVATION OF PANGOLINS NATIVE TO SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA 30 June – 2 July 2008, Singapore Zoo Edited by S. Pantel and S.Y. Chin Wildlife Reserves Singapore Group PROCEEDINGS OF THE WORKSHOP ON TRADE AND CONSERVATION OF PANGOLINS NATIVE TO SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA 30 JUNE –2JULY 2008, SINGAPORE ZOO EDITED BY S. PANTEL AND S. Y. CHIN 1 Published by TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia © 2009 TRAFFIC Southeast Asia All rights reserved. All material appearing in these proceedings is copyrighted and may be reproduced with permission. Any reproduction, in full or in part, of this publication must credit TRAFFIC Southeast Asia as the copyright owner. The views of the authors expressed in these proceedings do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC Network, WWF or IUCN. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership is held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint programme of WWF and IUCN. Layout by Sandrine Pantel, TRAFFIC Southeast Asia Suggested citation: Sandrine Pantel and Chin Sing Yun (ed.). 2009. Proceedings of the Workshop on Trade and Conservation of Pangolins Native to South and Southeast Asia, 30 June-2 July -

International and Domestic Pangolin Trade

INTERNATIONAL AND DOMESTIC PANGOLIN TRADE Dan Challender, IUCN Global Species Programme, IUCN SSC Pangolin Specialist Group INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR CONSERVATION OF NATURE OUTLINE 1. LEGAL/ILLEGAL TRADE 2. ILLEGAL TRADE 3. SMUGGLING/CROSS BORDER LAUNDERING 4. IDENTIFICATION OF PANGOLINS IN TRADE 5. USES 6. REGULATORY MEASURES 2 LEGAL/ILLEGAL TRADE • Commercial trade in pangolins since early 20th century • Pre-CITES – Tens of tonnes of scales, Indonesia to East Asia, 1925-1960 – Annual harvest in China 1960s-80s, 160,000 animals annually – Tens of thousands of skins, 1950s-70s, SE Asia to Taiwan (P.R. China) 3 LEGAL/ILLEGAL TRADE • By 1975, CITES and (current) legal protection – Asia/Africa • Heavy hunting for international trade in Asia • Trade reported to CITES (1975-2012), c.576,000 animals • Little reported within/from Africa • Also, handbags, shoes, belts, leather items… Illegal trade Trade reported to CITES 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 Estimated no. of pangolins/'000s 10 0 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Time 4 Source: Challender et al. 2015 LEGAL/ILLEGAL TRADE • Hunting/trade driven population declines, Asia (CITES RST, 1999) • Up to 2000, much illegal, international trade also taking place. • At least 88-163% higher than CITES trade (Challender et al. 2015) • E.g., tens of tonnes of scales to China/Taiwan/South Korea annually • This is against the backdrop of domestic harvest and trade taking place e.g., for consumption/use of scales. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

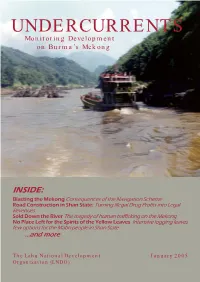

UNDERCURRENTS Monitoring Development on Burma’S Mekong

UNDERCURRENTS Monitoring Development on Burma’s Mekong INSIDE: Blasting the Mekong Consequences of the Navigation Scheme Road Construction in Shan State: Turning Illegal Drug Profits into Legal Revenues Sold Down the River The tragedy of human trafficking on the Mekong No Place Left for the Spirits of the Yellow Leaves Intensive logging leaves few options for the Mabri people in Shan State ...and more The Lahu National Development January 2005 Organization (LNDO) The Mekong/ Lancang The Mekong River is Southeast Asia’s longest, stretching from its source in Tibet to the delta of Vietnam. Millions of people depend on it for agriculture and fishing, and accordingly it holds a special cultural significance. For 234 kilometers, the Mekong forms the border between Burma’s Shan State and Luang Nam Tha and Bokeo provinces of Laos. This stretch includes the infamous “Golden Triangle”, or where Burma, Laos and Thailand meet, which has been known for illicit drug production. Over 22,000 primarily indigenous peoples live in the mountainous region of this isolated stretch of the river in Burma. The main ethnic groups are Akha, Shan, Lahu, Sam Tao (Loi La), Chinese, and En. The Mekong River has a special significance for the Lahu people. Like the Chinese, we call it the Lancang, and according to legends, the first Lahu people came from the river’s source. Traditional songs and sayings are filled with references to the river. True love is described as stretching form the source of the Mekong to the sea. The beauty of a woman is likened to the glittering scales of a fish in the Mekong. -

Observations of the Illegal Pangolin Trade in Lao PDR (PDF, 3

TRAFFIC OBSERVATIONS OF THE ILLEGAL REPORT PANGOLIN TRADE IN LAO PDR SEPTEMBER 2016 Lalita Gomez, Boyd T.C. Leupen and Sarah Heinrich TRAFFIC Report: Observations of the illegal pangolin trade in Lao PDR i TRAFFIC REPORT TRAFFIC, the wild life trade monitoring net work, is the leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF and IUCN. Reprod uction of material appearing in this report requires written permission from the publisher. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations con cern ing the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views of the authors expressed in this publication are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect those of TRAFFIC, WWF or IUCN. Published by TRAFFIC. Southeast Asia Regional Office Unit 3-2, 1st Floor, Jalan SS23/11 Taman SEA, 47400 Petaling Jaya Selangor, Malaysia Telephone : (603) 7880 3940 Fax : (603) 7882 0171 Copyright of material published in this report is vested in TRAFFIC. © TRAFFIC 2016. ISBN no: 978-983-3393-54-1 UK Registered Charity No. 1076722. Suggested citation: Gomez, L., Leupen, B T.C., Heinrich, S. (2016). Observations of the illegal pangolin trade in Lao PDR. TRAFFIC, -

Mong La: Business As Usual in the China-Myanmar Borderlands

Mong La: Business as Usual in the China-Myanmar Borderlands Alessandro Rippa, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich Martin Saxer, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich The aim of this project is to lay the conceptual groundwork for a new understanding of the positionality of remote areas around the globe. It rests on the hypothesis that remoteness and connectivity are not independent features but co-constitute each other in particular ways. In the context of this project, Rippa and Saxer conducted exploratory fieldwork together in 2015 along the China-Myanmar border. This collaborative photo essay is one result of their research. They aim to convey an image of Mong La that goes beyond its usual depiction as a place of vice and unruliness, presenting it, instead, as the outcome of a particular China-inspired vision of development. Infamous Mong La It is 6:00 P.M. at the main market of Mong La, the largest town in the small autonomous strip of land on the Chinese border formally known in Myanmar as Special Region 4. A gambler from China’s northern Heilongjiang Province just woke up from a nap. “I’ve been gambling all morning,” he says, “but after a few hours it is better to stop. To rest your brain.” He will go back to the casino after dinner, as he did for the entire month he spent in Mong La. Like him, hundreds of gamblers crowd the market, where open-air restaurants offer food from all over China. A small section of the market is dedicated to Mong La’s most infamous commodity— wildlife. -

Smutsia Temminckii – Temminck's Ground Pangolin

Smutsia temminckii – Temminck’s Ground Pangolin African Pangolin Working Group and the IUCN Species Survival Commission Pangolin Specialist Group) is Temminck’s Ground Pangolin. No subspecies are recognised. Assessment Rationale The charismatic and poorly known Temminck’s Ground Pangolin, while widely distributed across the savannah regions of the assessment region, are severely threatened by electrified fences (an estimated 377–1,028 individuals electrocuted / year), local and international bushmeat and traditional medicine trades (since 2010, the number of Darren Pietersen confiscations at ports / year has increased exponentially), road collisions (an estimated 280 killed / year) and incidental mortalities in gin traps. The extent of occurrence Regional Red List status (2016) Vulnerable A4cd*†‡ has been reduced by an estimated 9–48% over 30 years National Red List status (2004) Vulnerable C1 (1985 to 2015), due to presumed local extinction from the Free State, Eastern Cape and much of southern KwaZulu- Reasons for change No change Natal provinces. However, the central interior (Free State Global Red List status (2014) Vulnerable A4d and north-eastern Eastern Cape Province) were certainly never core areas for this species and thus it is likely that TOPS listing (NEMBA) (2007) Vulnerable the corresponding population decline was far lower overall CITES listing (2000) Appendix II than suggested by the loss of EOO. Additionally, rural settlements have expanded by 1–9% between 2000 and Endemic No 2013, which we infer as increasing poaching pressure and *Watch-list Data †Watch-list Threat ‡Conservation Dependent electric fence construction. While throughout the rest of Africa, and Estimated mature population size ranges widely increasingly within the assessment region, local depending on estimates of area of occupancy, from 7,002 and international illegal trade for bushmeat and to 32,135 animals. -

Fire and Ice: Conflict and Drugs in Myanmar’S Shan State

Fire and Ice: Conflict and Drugs in Myanmar’s Shan State Asia Report N°299 | 8 January 2019 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 149 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. A Long Legacy ................................................................................................................... 3 III. A New Drug Dynamic ....................................................................................................... 6 A. A Surge in Production ................................................................................................ 6 B. Tip of the Iceberg ....................................................................................................... 10 IV. The Links Between Drugs and Conflict ............................................................................ 12 A. Current Conflict Dynamics ........................................................................................ 12 B. The Role of the Drug Trade in the Conflict................................................................ 13 C. Ethno-political Clashes, Anti-drug Raids or Bank Heists? ....................................... 15 D. Why Is There Not -

Karl Ammann Dale Peterson

Photos: KARL AMMANN Text: DALE PETERSON Far left to right: A traditional Chinese medicine display in Mong La’s central market; a baby black bear for sale as meat; fresh game meat fetches top prices; a Sambar deer. 6/2007 | 45 THE ROAD to the town of Mong La in Myanmar’s Shan State twists through moun- tains of swaying forest and swirling bamboo, sudden drop-offs and breathtaking vistas, turns past Buddhist shrines and temples and monasteries. It drops into valleys where the land flattens and shatters into brown and Still, Mong La is a Buddhist town, and after lunch and green rice paddies, marked by clusters of then a hotel check-in, we drive to the top of the hill at the bamboo-sided and straw-thatched houses on centre of town and climb to the summit of the great golden AG CHINA stilts and animated by grazing water buffalo temple and pagoda. Mong La is surrounded by high hills, but and cone-hatted farmers bent at the waist in the yellow sun, the upside-down ice cream cone of the golden pagoda reaches pulling up clumps of green rice and slapping them into the high enough to rival those hills, and in the late afternoon, Bhutan brown water. The setting is serenely pastoral, and since we we stand up there and look over the town, while the sounds India have travelling during the dry season, the predominant col- of puttering motorbikes and chugging Chinese tractors, of our is brown, while the main smells and tastes are subtly as- children’s high-pitched voices and laughter, and a cock-a-doo- Myitkyina Yunnan sociated with dust… until, suddenly, from out of the dry land dle cacophony of cocks – those sounds rise and turn insub- Bangladesh and the brown-watered valleys emerges a flood of lush, green stantial, and a mild breeze attenuates the heat of the day. -

Sin City: Illegal Wildlife Trade in Laos' Special Economic Zone

SIN CITY Illegal wildlife trade in Laos’ Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS CONTENTS This report was written by the Environmental Investigation Agency. 2 INTRODUCTION Special thanks to Education for Nature Vietnam (ENV), the Rufford Foundation, Ernest Kleinwort 3 PROFILE OF THE GOLDEN TRIANGLE SPECIAL Charitable Trust, Save Wild Tigers and Michael Vickers. ECONOMIC ZONE & KINGS ROMANS GROUP Report design by: 5 WILDLIFE TRADE AT THE GT SEZ www.designsolutions.me.uk March 2015 7 REGIONAL WILDLIFE CRIME HOTSPOTS All images © EIA/ENV unless otherwise stated. 9 ILLEGAL WILDLIFE SUPERMARKET 11 LAWLESSNESS IN THE GOLDEN TRIANGLE SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONE 13 WILDLIFE CLEARING HOUSE: LAOS’ ROLE IN REGIONAL AND GLOBAL WILDLIFE TRADE 16 CORRUPTION & A LACK OF CAPACITY 17 DEMAND DRIVERS OF TIGER TRADE IN LAOS 19 CONCLUSIONS 20 RECOMMENDATIONS ENVIRONMENTAL INVESTIGATION AGENCY (EIA) 62/63 Upper Street, London N1 0NY, UK Tel: +44 (0) 20 7354 7960 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7354 7961 email: [email protected] www.eia-international.org EIA US P.O.Box 53343 Washington DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 483 6621 Fax: +202 986 8626 email: [email protected] COVER IMAGE: © Monkey Business Images | Dreamstime.com 1 INTRODUCTION This report takes a journey to a dark corner of north-west Lao PDR (hereafter referred to as Laos), in the heart of the Golden Triangle in South-East Asia. The Environmental Investigation While Laos’ wildlife laws are weak, there The blatant illegal wildlife trade by Agency (EIA) and Education for Nature is not even a pretence of enforcement in Chinese companies in this part of Laos Vietnam (ENV) have documented how the GT SEZ. -

Displaced Burmese Women in Burma and Thailand

WOMEN’S COMMISSION for refugeew women & children FEAR AND HOPE: Displaced Burmese Women in Burma and Thailand March 2000 WOMEN’S COMMISSION for refugeew women & children Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children 122 East 42nd Street New York, NY 10168-1289 tel.212.551.3111 or 3088 fax. 212.551.3180 [email protected] www.womenscommission.org © November 2000 by Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN:1-58030-007-3 MISSION STATEMENT The Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children seeks to improve the lives of refugee women, children and adolescents through a vigorous program of public education and advocacy and by acting as a technical resource. Founded in 1989 under the auspices of the International Rescue Committee, the Women’s Commission is the first organization in the United States dedicated solely to speaking out on behalf of women and children uprooted by armed conflict or persecution. Acknowledgments The Women’s Commission would like to thank the MacArthur Foundation, Ford Foundation, Joyce Mertz- Gilmore Foundation and the J.P. Morgan Charitable Trust, without whose support this report would not have been possible. The delegation also thanks the International Rescue Committee in Thailand, in particular its Director, Lori Bell, and the United States Embassy in Rangoon, whose help was invaluable. The delegation comprised Kathleen Newland, Chair of the Women’s Commission Board and a Senior Associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; Mary Anne Schwalbe, member of the Women’s Commission’s Board and a volunteer at the International Rescue Committee; Ellen Jorgensen, Development Director at the Women’s Commission; Erin Kenny, a Master’s Degree student at the Columbia School of Public Health; and Louisa Conrad, a student at the Nightingale-Bamford School in New York.