The Illegal Wildlife Trade: Through the Eyes of a One-Year-Old Pangolin (Manis Javanica)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autecology of the Sunda Pangolin (Manis Javanica) in Singapore

AUTECOLOGY OF THE SUNDA PANGOLIN (MANIS JAVANICA) IN SINGAPORE LIM T-LON, NORMAN (B.Sc. (Hons.), NUS) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2007 An adult male Manis javanica (MJ17) raiding an arboreal Oceophylla smaradgina nest. By shutting its nostrils and eyes, the Sunda Pangolin is able to protect its vulnerable parts from the powerful bites of this ant speces. The scales and thick skin further reduce the impacts of the ants’ attack. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My supervisor Professor Peter Ng Kee Lin is a wonderful mentor who provides the perfect combination of support and freedom that every graduate student should have. Despite his busy schedule, he always makes time for his students and provides the appropriate advice needed. His insightful comments and innovative ideas never fail to impress and inspire me throughout my entire time in the University. Lastly, I am most grateful to Prof. Ng for seeing promise in me and accepting me into the family of the Systematics and Ecology Laboratory. I would also like to thank Benjamin Lee for introducing me to the subject of pangolins, and subsequently introducing me to Melvin Gumal. They have guided me along tremendously during the preliminary phase of the project and provided wonderful comments throughout the entire course. The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) provided funding to undertake this research. In addition, field biologists from the various WCS offices in Southeast Asia have helped tremendously throughout the project, especially Anthony Lynam who has taken time off to conduct a camera-trapping workshop. -

Pangolin Trade in the Mong La Wildlife Market and the Role of Myanmar in the Smuggling of Pangolins Into China

Global Ecology and Conservation 5 (2016) 118–126 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Global Ecology and Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gecco Original research article Pangolin trade in the Mong La wildlife market and the role of Myanmar in the smuggling of pangolins into China Vincent Nijman a, Ming Xia Zhang b, Chris R. Shepherd c,∗ a Oxford Wildlife Trade Research Group, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK b Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Gardens, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Mengla, China c TRAFFIC, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia article info a b s t r a c t Article history: We report on the illegal trade in live pangolins, their meat, and their scales in the Special Received 7 November 2015 Development Zone of Mong La, Shan State, Myanmar, on the border with China, and Received in revised form 18 December 2015 present an analysis of the role of Myanmar in the trade of pangolins into China. Mong Accepted 18 December 2015 La caters exclusively for the Chinese market and is best described as a Chinese enclave in Myanmar. We surveyed the morning market, wildlife trophy shops and wild meat restaurants during four visits in 2006, 2009, 2013–2014, and 2015. We observed 42 bags Keywords: of scales, 32 whole skins, 16 foetuses or pangolin parts in wine, and 27 whole pangolins for Burma CITES sale. Our observations suggest Mong La has emerged as a significant hub of the pangolin Conservation trade. The origin of the pangolins is unclear but it seems to comprise a mixture of pangolins Manis from Myanmar and neighbouring countries, and potentially African countries. -

PROCEEDINGS of the WORKSHOP on TRADE and CONSERVATION of PANGOLINS NATIVE to SOUTH and SOUTHEAST ASIA 30 June – 2 July 2008, Singapore Zoo Edited by S

PROCEEDINGS OF THE WORKSHOP ON TRADE AND CONSERVATION OF PANGOLINS NATIVE TO SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA 30 June – 2 July 2008, Singapore Zoo Edited by S. Pantel and S.Y. Chin Wildlife Reserves Singapore Group PROCEEDINGS OF THE WORKSHOP ON TRADE AND CONSERVATION OF PANGOLINS NATIVE TO SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA 30 JUNE –2JULY 2008, SINGAPORE ZOO EDITED BY S. PANTEL AND S. Y. CHIN 1 Published by TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia © 2009 TRAFFIC Southeast Asia All rights reserved. All material appearing in these proceedings is copyrighted and may be reproduced with permission. Any reproduction, in full or in part, of this publication must credit TRAFFIC Southeast Asia as the copyright owner. The views of the authors expressed in these proceedings do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC Network, WWF or IUCN. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership is held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint programme of WWF and IUCN. Layout by Sandrine Pantel, TRAFFIC Southeast Asia Suggested citation: Sandrine Pantel and Chin Sing Yun (ed.). 2009. Proceedings of the Workshop on Trade and Conservation of Pangolins Native to South and Southeast Asia, 30 June-2 July -

Experts Convene to Save One of World's Most Trafficked Mammals

For immediate release 7 July 2017 Contacts: Joey Phua, Wildlife Reserves Singapore, +65 6210 5385, [email protected] Goska Bonnaveira, IUCN Media Relations, +41 79 276 0185, [email protected] Paul Thomson, IUCN Pangolin Specialist Group, +1 415 906 9955 [email protected] Images available here: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/0B4YRXkdvJ5rFYlNwOGdQWjFzbFE?usp=sharing Experts convene to save one of world’s most trafficked mammals Saving the Sunda pangolin – one of the world’s most trafficked mammals – from extinction will require engaging local communities in their conservation and addressing the demand for pangolin products, according to international wildlife experts gathered in Singapore this week to create the first ever conservation strategy for the species. Pangolins are scaly insect-eating animals that live in Asia and Africa. The Sunda pangolin (Manis javanica), one of eight species of pangolin, lives in Southeast Asia and is classified as Critically Endangered by The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened SpeciesTM. A thriving illegal trade for pangolin meat and scales is behind the decline. An estimated 200,000 Sunda pangolins have been illegally traded in the last decade, according to the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) Pangolin Specialist Group. A range of interventions will be needed to conserve the Sunda pangolin, according to a group of more than 50 conservationists, researchers and wildlife authorities representing 16 countries gathered in Singapore for the workshop. Priorities include combatting trafficking, strengthening legal policies, and building capacity for effective enforcement, “The sheer scale of the pangolin trade is staggering, and time is of the essence,” says Dr. -

International and Domestic Pangolin Trade

INTERNATIONAL AND DOMESTIC PANGOLIN TRADE Dan Challender, IUCN Global Species Programme, IUCN SSC Pangolin Specialist Group INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR CONSERVATION OF NATURE OUTLINE 1. LEGAL/ILLEGAL TRADE 2. ILLEGAL TRADE 3. SMUGGLING/CROSS BORDER LAUNDERING 4. IDENTIFICATION OF PANGOLINS IN TRADE 5. USES 6. REGULATORY MEASURES 2 LEGAL/ILLEGAL TRADE • Commercial trade in pangolins since early 20th century • Pre-CITES – Tens of tonnes of scales, Indonesia to East Asia, 1925-1960 – Annual harvest in China 1960s-80s, 160,000 animals annually – Tens of thousands of skins, 1950s-70s, SE Asia to Taiwan (P.R. China) 3 LEGAL/ILLEGAL TRADE • By 1975, CITES and (current) legal protection – Asia/Africa • Heavy hunting for international trade in Asia • Trade reported to CITES (1975-2012), c.576,000 animals • Little reported within/from Africa • Also, handbags, shoes, belts, leather items… Illegal trade Trade reported to CITES 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 Estimated no. of pangolins/'000s 10 0 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Time 4 Source: Challender et al. 2015 LEGAL/ILLEGAL TRADE • Hunting/trade driven population declines, Asia (CITES RST, 1999) • Up to 2000, much illegal, international trade also taking place. • At least 88-163% higher than CITES trade (Challender et al. 2015) • E.g., tens of tonnes of scales to China/Taiwan/South Korea annually • This is against the backdrop of domestic harvest and trade taking place e.g., for consumption/use of scales. -

Observations of the Illegal Pangolin Trade in Lao PDR (PDF, 3

TRAFFIC OBSERVATIONS OF THE ILLEGAL REPORT PANGOLIN TRADE IN LAO PDR SEPTEMBER 2016 Lalita Gomez, Boyd T.C. Leupen and Sarah Heinrich TRAFFIC Report: Observations of the illegal pangolin trade in Lao PDR i TRAFFIC REPORT TRAFFIC, the wild life trade monitoring net work, is the leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF and IUCN. Reprod uction of material appearing in this report requires written permission from the publisher. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations con cern ing the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views of the authors expressed in this publication are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect those of TRAFFIC, WWF or IUCN. Published by TRAFFIC. Southeast Asia Regional Office Unit 3-2, 1st Floor, Jalan SS23/11 Taman SEA, 47400 Petaling Jaya Selangor, Malaysia Telephone : (603) 7880 3940 Fax : (603) 7882 0171 Copyright of material published in this report is vested in TRAFFIC. © TRAFFIC 2016. ISBN no: 978-983-3393-54-1 UK Registered Charity No. 1076722. Suggested citation: Gomez, L., Leupen, B T.C., Heinrich, S. (2016). Observations of the illegal pangolin trade in Lao PDR. TRAFFIC, -

Smutsia Temminckii – Temminck's Ground Pangolin

Smutsia temminckii – Temminck’s Ground Pangolin African Pangolin Working Group and the IUCN Species Survival Commission Pangolin Specialist Group) is Temminck’s Ground Pangolin. No subspecies are recognised. Assessment Rationale The charismatic and poorly known Temminck’s Ground Pangolin, while widely distributed across the savannah regions of the assessment region, are severely threatened by electrified fences (an estimated 377–1,028 individuals electrocuted / year), local and international bushmeat and traditional medicine trades (since 2010, the number of Darren Pietersen confiscations at ports / year has increased exponentially), road collisions (an estimated 280 killed / year) and incidental mortalities in gin traps. The extent of occurrence Regional Red List status (2016) Vulnerable A4cd*†‡ has been reduced by an estimated 9–48% over 30 years National Red List status (2004) Vulnerable C1 (1985 to 2015), due to presumed local extinction from the Free State, Eastern Cape and much of southern KwaZulu- Reasons for change No change Natal provinces. However, the central interior (Free State Global Red List status (2014) Vulnerable A4d and north-eastern Eastern Cape Province) were certainly never core areas for this species and thus it is likely that TOPS listing (NEMBA) (2007) Vulnerable the corresponding population decline was far lower overall CITES listing (2000) Appendix II than suggested by the loss of EOO. Additionally, rural settlements have expanded by 1–9% between 2000 and Endemic No 2013, which we infer as increasing poaching pressure and *Watch-list Data †Watch-list Threat ‡Conservation Dependent electric fence construction. While throughout the rest of Africa, and Estimated mature population size ranges widely increasingly within the assessment region, local depending on estimates of area of occupancy, from 7,002 and international illegal trade for bushmeat and to 32,135 animals. -

Pangolin-Id-Guide-Rast-English.Pdf

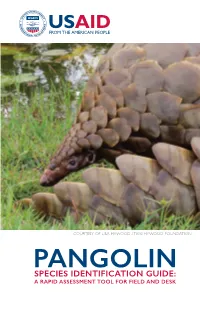

COURTESY OF LISA HYWOOD / TIKKI HYWOOD FOUNDATION PANGOLIN SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE: A RAPID ASSESSMENT TOOL FOR FIELD AND DESK Citation: Cota-Larson, R. 2017. Pangolin Species Identification Guide: A Rapid Assessment Tool for Field and Desk. Prepared for the United States Agency for International Development. Bangkok: USAID Wildlife Asia Activity. Available online at: http://www.usaidwildlifeasia.org/resources. Cover: Ground Pangolin (Smutsia temminckii). Photo: Lisa Hywood/Tikki Hywood Foundation For hard copies, please contact: USAID Wildlife Asia, 208 Wireless Road, Unit 406 Lumpini, Pathumwan, Bangkok 10330 Thailand Tel: +66 20155941-3, Email: [email protected] About USAID Wildlife Asia The USAID Wildlife Asia Activity works to address wildlife trafficking as a transnational crime. The project aims to reduce consumer demand for wildlife parts and products, strengthen law enforcement, enhance legal and political commitment, and support regional collaboration to reduce wildlife crime in Southeast Asia, particularly Cambodia; Laos; Thailand; Vietnam, and China. Species focus of USAID Wildlife Asia include elephant, rhinoceros, tiger, and pangolin. For more information, please visit www.usaidwildlifeasia.org Disclaimer The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. ANSAR KHAN / LIFE LINE FOR NATURE SOCIETY CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 2 HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE 2 INTRODUCTION TO PANGOLINS 3 RANGE MAPS 4 SPECIES SUMMARIES 6 HEADS AND PROFILES 10 SCALE DISTRIBUTION 12 FEET 14 TAILS 16 SCALE SAMPLES 18 SKINS 22 PANGOLIN PRODUCTS 24 END NOTES 28 REGIONAL RESCUE CENTER CONTACT INFORMATION 29 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS TECHNICAL ADVISORS: Lisa Hywood (Tikki Hywood Foundation) and Quyen Vu (Education for Nature-Vietnam) COPY EDITORS: Andrew W. -

Scaling up Pangolin Conservation

July 2014 SCALING UP PANGOLIN CONSERVATION IUCN SSC Pangolin Specialist Group Conservation Action Plan Compiled by Daniel W. S. Challender, Carly Waterman and Jonathan E. M. Baillie SCALING UP PANGOLIN CONSERVATION IUCN SSC Pangolin Specialist Group Conservation Action Plan July 2014 Compiled by Daniel W. S. Challender, Carly Waterman and Jonathan E. M. Baillie IUCN SSC Pangolin Specialist Group C/o Zoological Society of London Regent’s Park London England NW1 4RY W: www.pangolinsg.org F: IUCN/SSC Pangolin Specialist Group T: @PangolinSG Cover photo: Temminck’s ground pangolin © Scott & Judy Hurd Suggested citation: Challender, DWS, Waterman, C, and Baillie, JEM. 2014. Scaling up pangolin conservation. IUCN SSC Pangolin Specialist Group Conservation Action Plan. Zoological Society of London, London, UK. 1 Acknowledgements It would have been impossible to produce this The meeting would not have been possible without action plan, or hold the 1st IUCN SSC Pangolin the generous financial and/or in-kind support from a Specialist Group Conservation Conference in number of organisations, specifically the Wildlife June 2013 from which it emanates, without the Reserves Singapore Conservation Fund. commitment and enthusiasm of a large number of people, and the support of a number of Thanks are also extended to the International Union organisations committed to pangolin conservation. for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Species Survival Commission (SSC), the Zoological Society of London Thanks are extended to all members of the IUCN SSC (ZSL), San Antonio Zoo, Houston Zoo, TRAFFIC, Pangolin Specialist Group, and both members and and Ocean Park Conservation Foundation Hong Kong. non-members for their passion and dedication Particular thanks also to Sonja Luz and her team at throughout the four day conference, specifically: the Night Safari, Wildlife Reserves Singapore, for their Gary Ades, Claire Beastall, Bosco Chan, logistical and organizational support throughout Ya Ting Chan, Jason Chin, Ju lian Chong, Yi Fei the event. -

Developing Release Protocols for Trade-Confiscated Sunda Pangolins (Manisjavanica) Through a Monitored Release in Cat Tien National Park, Vietnam

Developing release protocols for trade-confiscated Sunda Pangolins (Manisjavanica) through a monitored release in Cat Tien National Park, Vietnam. Organisation:The Carnivore and Pangolin Conservation Program (CPCP) Principle Investigator: Tran Quang Phuong Co Investigators: Daniel Wilcox (Feb 2011-June 2012); Louise Fletcher (January 2012-June 2014) Other Project Staff: Nguyen The Truong An; Luong Tat Hung; Dinh Van Than; Bui Van Thu; Dinh Van Quyen; Dinh Van Trung; Dinh Van Tuan. The Sunda pangolin (Manis javanica) is one of the most exploited species in Southeast Asia and is illegally traded in huge quantities. Despite many recent advances in the husbandry for this species, much of the ecology and biology of this unusual mammal remains unknown. Forest Protection Department (FPD) Rangers often release pangolins into protected areas with no post-release monitoring and no data to confirm that this is a viable placement option. This project aimed to clarify whether release into a protected area is a viable placement option through a monitored release and in doing so simultaneously generated data on the ecology, biology and wild behaviours of this species. This data can be used to improve the effectiveness of both in-situ and ex-situ conservation activities. Objectives: 1. To improve the ability to accurately assess the health and reproductive status of trade-confiscated Sunda Pangolins. 2. To initiate and develop a genetic reference library so that the provenance of trade-confiscated Sunda Pangolins can be compared and analyzed, once samples from all range countries have been collected. 3. To investigate and verify whether release into a protected area in Vietnam is a viable placement option for fully-rehabilitated trade-confiscated Sunda Pangolins. -

Sunda Pangolin, Manis Javanica

Sunda pangolin, Manis javanica Compiler: Sodsai, W. Contributors: Gray, C.; Amin, R.; Pollini, B.; Thomas, W.; Larney, E.; Thampitak, S.; Sapantupong, A.; Namsupak, S.; Yindee, M.; Sookmasuang, R. Suggested citation: Sodsai, W. et al. A Survival Blueprint for the conservation and management of the Sunda Pangolin in Thailand. An output from the EDGE of Existence fellowship, Zoological Society of London, 2018. 1. STATUS REVIEW 1.1 Taxonomy: Mammalia > Pholidota > Manidae > Manis > javanica (Although Palawan in the Philippines was previously thought to be a stronghold for this species, here the species has since been re-categorized as the Philippine pangolin under the name Manis culionensis by Feiler (1998) and subsequently by Gaubert and Antunes (2005)). English: Sunda Pangolin, Malayan Pangolin French: Pangolin Javanais, Pangolin Malais Spanish: Pangolín Malayo 1.2 Distribution and population status: 1.2.1 Global distribution: “The highlighted text has been reproduced with permission from the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species account for the Sunda Pangolin, as available June 2018” (Challender et al. 2014). The species is widely distributed geographically, occurring across Southeast East Asia, from southern China and Myanmar through to lowland Lao PDR and including much of Thailand, central and southern Viet Nam, Cambodia, Peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra, Java and adjacent islands (Indonesia) and Borneo (Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei). However, the northern and western limits of its range are poorly known (Schlitter 2005, Wu et al. 2005). It has been recorded from sea level up to 1,700 m above sea level. Population Country estimate Distribution Population trend Notes (plus (plus references) references) Myanmar There is This species is distributed in central and There is no recent data on the status of This species is rarely virtually no southern Myanmar (Corbet and Hill 1992, this species in Myanmar. -

A Note on the Illegal Trade and Use of Pangolin Body Parts in India

S H O R T C O M M U N I C A T I O N A note on the illegal trade and use of pangolin body parts in India Rajesh Kumar Mohapatra, Sudarsan Panda, Manoj V. Nair, Lakshmi Narayan Acharjyo and Daniel W.S. Challender INTRODUCTION f the eight extant species of pangolin (Pholidota: Manidae), the Indian Pangolin Manis crassicaudata and Chinese Pangolin M. pentadactyla occur in India (Figs. 1, 2 and 6). MOHAPATRA RAJESH K. OThe Indian Pangolin is widely distributed across Fig. 1. Indian Pangolin Manis crassicaudata. the country, occurring in Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Delhi, Gujarat, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal. The species also occurs rapidly declining populations (Challender et al., 2014a; in Bangladesh, Pakistan, Nepal and Sri Lanka Challender, 2011; Baillie et al., 2014). Hunting, poaching and (Srinivasulu and Srinivasulu, 2004; Baillie et al., associated trade takes place despite both species being listed 2014). The Chinese Pangolin is native only to the on Schedule I of India’s Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, which north and north-eastern States of India, including strictly prohibits these activities. Moreover, since 1975 both the Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Meghalaya, Nagaland Chinese and Indian pangolins have been included in Appendix II and Sikkim, and also occurs in Bangladesh, of CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Bhutan, Nepal, Myanmar, China, Lao PDR, Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, to which an annotation was Taiwan (P.R. China), Thailand and Viet Nam added at the 11th meeting of the Conference of the Parties in (Srinivasulu and Srinivasulu, 2004; Challender et 2000.