Institutionalization of the Japanese Diet Based On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implications of Abenomics on Gender Equality in Japan and Its Conformity with CEDAW

TUCKER (DO NOT DELETE) 4/24/2017 6:16 PM RICKY TUCKER* Implications of Abenomics on Gender Equality in Japan and Its Conformity with CEDAW Introduction ....................................................................................... 544 A. Abenomics ...................................................................... 545 B. Female Workforce Participation ..................................... 546 C. History of Japanese Gender Equality Laws .................... 549 I. The Purpose of the Third Arrow Casts Doubt on its Ability to Accomplish Its Goals ............................................. 551 A. Addressing Financial Insecurity ..................................... 551 B. Addressing Gender Equality ........................................... 552 II. The Third Arrow Does Not Conform to the Strict Mandates Imposed Upon Member Countries to CEDAW ..... 554 A. Leadership ......................................................................... 555 1. CEDAW Article II .................................................... 556 2. CEDAW Article XI ................................................... 558 B. Childcare Waiting Lists .................................................. 559 C. Support for a Return to Work ......................................... 561 D. Assistance for Reentering the Workforce ....................... 563 III. Abenomics’ Conformity with CEDAW and the Overall Goal of Boosting the Economy Are Not Mutually Exclusive ................................................................................ 564 IV. A Counterpoint: -

Election System in Japan

地方自治研修 Local Governance (Policy Making and Civil Society) F.Y.2007 Election System in Japan 選挙制度 – CONTENTS – CHAPTER I. BASIC PRINCIPLES OF JAPAN’S ELECTION SYSTEM .........................................1 CHAPTER II. THE LAW CONCERNING ELECTIONS FOR PUBLIC OFFICES.........................3 CHAPTER III. ORGANS FOR ELECTION MANAGEMENT ...........................................................5 CHAPTER IV. TECHNICAL ADVICE, RECOMMENDATION, ETC. OF ELECTIONS...........7 CHAPTER V. SUFFRAGE.......................................................................................................................8 CHAPTER VI. ELIGIBILITY FOR ELECTION..................................................................................9 CHAPTER VII. ELECTORAL DISTRICTS........................................................................................10 CHAPTER VIII. VOTERS LIST ...........................................................................................................15 CHAPTER IX. CANDIDATURE - RUNNING FOR ELECTION .....................................................17 CHAPTER X. BALLOTING ..................................................................................................................22 CHAPTER XI. BALLOT COUNTING AND DETERMINATION OF PERSONS ELECTED...29 CHAPTER XII. ELECTION CAMPAIGNS.........................................................................................33 CHAPTER XIII. ELECTION CAMPAIGN REVENUE AND EXPENDITURES ...........................44 CHAPTER XIV. LAWSUITS.................................................................................................................49 -

RSF 190X270 Classement4:Mise En Page 1 31/01/14 15:47 Page 1

RSF_190x270_Classement4:Mise en page 1 31/01/14 15:47 Page 1 WORLD PRESS FREEDOM INDEX 2014 RSF_190x270_Classement4:Mise en page 1 31/01/14 15:47 Page 2 World Press Freedom index - Methodology The press freedom index that Reporters Without occupying force are treated as violations of the right to Borders publishes every year measures the level of information in foreign territory and are incorporated into freedom of information in 180 countries. It reflects the the score of the occupying force’s country. degree of freedom that journalists, news organizations The rest of the questionnaire, which is sent to outside and netizens enjoy in each country, and the efforts experts and members of the RWB network, made by the authorities to respect and ensure respect concentrates on issues that are hard to quantify such for this freedom. as the degree to which news providers censor It is based partly on a questionnaire that is sent to our themselves, government interference in editorial partner organizations (18 freedom of expression NGOs content, or the transparency of government decision- located in all five continents), to our network of 150 making. Legislation and its effectiveness are the subject correspondents, and to journalists, researchers, jurists of more detailed questions. Questions have been and human rights activists. added or expanded, for example, questions about The 180 countries ranked in this year’s index are those concentration of media ownership and favouritism for which Reporters Without Borders received in the allocation of subsidies or state advertising. completed questionnaires from various sources. Some Similarly, discrimination in access to journalism and countries were not included because of a lack of reliable, journalism training is also included. -

The History Problem: the Politics of War

History / Sociology SAITO … CONTINUED FROM FRONT FLAP … HIRO SAITO “Hiro Saito offers a timely and well-researched analysis of East Asia’s never-ending cycle of blame and denial, distortion and obfuscation concerning the region’s shared history of violence and destruction during the first half of the twentieth SEVENTY YEARS is practiced as a collective endeavor by both century. In The History Problem Saito smartly introduces the have passed since the end perpetrators and victims, Saito argues, a res- central ‘us-versus-them’ issues and confronts readers with the of the Asia-Pacific War, yet Japan remains olution of the history problem—and eventual multiple layers that bind the East Asian countries involved embroiled in controversy with its neighbors reconciliation—will finally become possible. to show how these problems are mutually constituted across over the war’s commemoration. Among the THE HISTORY PROBLEM THE HISTORY The History Problem examines a vast borders and generations. He argues that the inextricable many points of contention between Japan, knots that constrain these problems could be less like a hang- corpus of historical material in both English China, and South Korea are interpretations man’s noose and more of a supportive web if there were the and Japanese, offering provocative findings political will to determine the virtues of peaceful coexistence. of the Tokyo War Crimes Trial, apologies and that challenge orthodox explanations. Written Anything less, he explains, follows an increasingly perilous compensation for foreign victims of Japanese in clear and accessible prose, this uniquely path forward on which nationalist impulses are encouraged aggression, prime ministerial visits to the interdisciplinary book will appeal to sociol- to derail cosmopolitan efforts at engagement. -

Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know

1 Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know Edited by Parissa Haghirian Sophia University Tokyo, Japan 2 Contents About this Book ......................................................................................... 4 The Editor ................................................................................................ 5 Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know ................................................. 6 Contributors of This Book ............................................................................ 94 Bibliography ............................................................................................ 96 Further Reading on Japanese Management .................................................... 102 3 About this Book This book is the result of one of my “Management in Japan” classes held at the Faculty of Liberal Arts at Sophia University in Tokyo. Students wrote this dictionary entries, I edited and updated them. The document is now available as a free e-book at my homepage www.haghirian.com. We hope that this book improves understanding of Japanese management and serves as inspiration for anyone interested in the subject. Questions and comments can be sent to [email protected]. Please inform the editor if you plan to quote parts of the book. Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know Edited by Parissa Haghirian First edition, Tokyo, October 2019 4 The Editor Parissa Haghirian is Professor of International Management at Sophia University in Tokyo. She lives and works in Japan since 2004 -

The Birth of the Parliamentary Democracy in Japan: an Historical Approach

The Birth of the Parliamentary Democracy in Japan: An Historical Approach Csaba Gergely Tamás * I. Introduction II. State and Sovereignty in the Meiji Era 1. The Birth of Modern Japan: The First Written Constitution of 1889 2. Sovereignty in the Meiji Era 3. Separation of Powers under the Meiji Constitution III. The Role of Teikoku Gikai under the Meiji Constitution (明治憲法 Meiji Kenp ō), 1. Composition of the Teikoku Gikai ( 帝國議会) 2. Competences of the Teikoku Gikai IV. The Temporary Democracy in the 1920s 1. The Nearly 14 Years of the Cabinet System 2. Universal Manhood Suffrage: General Election Law of 1925 V. Constitutionalism in the Occupation Period and Afterwards 1. The Constitutional Process: SCAP Draft and Its Parliamentary Approval 2. Shōch ō ( 象徴) Emperor: A Mere Symbol? 3. Popular Sovereignty and the Separation of State Powers VI. Kokkai ( 国会) as the Highest Organ of State Power VII. Conclusions: Modern vs. Democratic Japan References I. INTRODUCTION Japanese constitutional legal history does not constitute a part of the obligatory legal curriculum in Hungary. There are limited numbers of researchers and references avail- able throughout the country. However, I am convinced that neither legal history nor comparative constitutional law could be properly interpreted without Japan and its unique legal system and culture. Regarding Hungarian-Japanese legal linkages, at this stage I have not found any evidence of a particular interconnection between the Japanese and Hungarian legal system, apart from the civil law tradition and the universal constitutional principles; I have not yet encountered the Hungarian “Lorenz von Stein” or “Hermann Roesler”. * This study was generously sponsored by the Japan Foundation Short-Term Fellowship Program, July-August, 2011. -

Chapter 1. Meiji Revolution: Start of Full-Scale Modernization

Seven Chapters on Japanese Modernization Chapter 1. Meiji Revolution: Start of Full-Scale Modernization Contents Section 1: Significance of Meiji Revolution Section 2: Legacies of the Edo Period Section 3: From the Opening of Japan to the Downfall of Bakufu, the Tokugawa Government Section 4: New Meiji Government Section 5: Iwakura Mission, Political Crisis of 1873 and the Civil War Section 6: Liberal Democratic Movement and the Constitution Section 7: End of the Meiji Revolution It’s a great pleasure to be with you and speak about Japan’s modernization. Japan was the first country and still is one of the very few countries that have modernized from a non-Western background to establish a free, democratic, prosperous, and peace- loving nation based on the rule of law, without losing much of its tradition and identity. I firmly believe that there are quite a few aspects of Japan’s experience that can be shared with developing countries today. Section 1: Significance of Meiji Revolution In January 1868, in the palace in Kyoto, it was declared that the Tokugawa Shogunate was over, and a new government was established under Emperor, based on the ancient system. This was why this political change was called as the Meiji Restoration. The downfall of a government that lasted more than 260 years was a tremendous upheaval, indeed. It also brought an end to the epoch of rule by “samurai,” “bushi” or Japanese traditional warriors that began as early as in the 12th century and lasted for about 700 years. Note: This lecture transcript is subject to copyright protection. -

The Constitution of Japan

University of Iceland School of Humanities Department of Japanese The Constitution of Japan The Road to Promulgation B.A. Thesis Viktoría Emma Berglindardóttir Kt.: 140992-2919 Supervisor: Kristín Ingvarsdóttir September 2017 THE CONSTITUTION OF JAPAN 2 Abstract American forces occupying Japan after World War II drafted the 1947 Constitution of Japan; later came to be known as the Peace Constitution through its renunciation of war. Liberal and idealistic, it brought to the Japanese people numerous rights, which they did not have before. Women were given equal rights to men; freedom of thought and religion were now inviolate; and education was made a right for all. These rights, along with many other changes, were brought to the country of Japan through the revision of their previous constitution, the Meiji Constitution. The difference between the two is immense. The latter placed the Emperor at the head of the state and proclaimed him to be sacred and inviolate. The people of Japan were defined merely as subjects of the Empire, as opposed to free citizens. The rights they had were few and could be limited by law. The radical change seen in the Peace Constitution is due to its American origins. This thesis will explore those origins, or to be more precise; the journey from conception to promulgation, and by what method an American draft attained promulgation. THE CONSTITUTION OF JAPAN 3 Table of Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................... 2 -

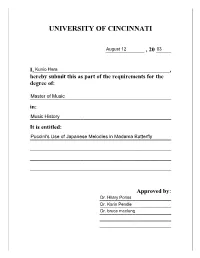

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ PUCCINI’S USE OF JAPANESE MELODIES IN MADAMA BUTTERFLY A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2003 by Kunio Hara B.M., University of Cincinnati, 2000 Committee Chair: Dr. Hilary Poriss ABSTRACT One of the more striking aspects of exoticism in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly is the extent to which the composer incorporated Japanese musical material in his score. From the earliest discussion of the work, musicologists have identified many Japanese melodies and musical characteristics that Puccini used in this work. Some have argued that this approach indicates Puccini’s preoccupation with creating an authentic Japanese setting within his opera; others have maintained that Puccini wanted to produce an exotic atmosphere -

Malapportionment of Representation in the National Diet

MALAPPORTIONMENT OF REPRESENTATION IN THE NATIONAL DIET HIROYUKI HATA* I INTRODUCTION Malapportionment of Diet seats is one of the most serious problems confronting contemporary Japan. After World War II, there was a large-scale population shift from rural to urban areas in Japan, as in other industrialized countries. However, the postwar statutes for apportionment of Diet members have not been fully revised to reflect this shift. This situation exists because the conservative Liberal Democratic Party and its predecessors, which have received their main support in the rural areas, have been in power ever since the war's end, except for a short period during which the Japan Socialist Party led the government. In the early 1960s, many Japanese people began to question the degree of malapportionment, and some concluded that it had passed the bounds of tolerance. At this time, the United States Supreme Court handed down its celebrated decision in Reynolds v. Sims I which established the principle of "one person, one vote." This decision undeniably helped ignite public sentiment in Japan for fair and just representation in the National Diet. Since the Diet did not fully respond to this demand, the people inevitably turned to the judiciary for improvement of the situation. Lawsuits have since been filed one after another in an effort to realize the electoral equality guaranteed by the Constitution. Yet, the present situation is still far from satisfactory. II THE CONSTITUTION AND AN OVERVIEW OF DEVELOPMENTS IN APPORTIONMENT LAW Under the Constitution, apportionment and districting are expressly within the discretion of the National Diet, which consists of the House of Representatives and the House of Councillors. -

Removal of the Ban on Meat

The End of a 1,200-year-old Ban on the Eating of Meat Removal of the Ban on Meat Introduction Zenjiro Watanabe Mr. Watanabe was born in Tokyo in 1932 and In March 1854, the Tokugawa Shogunate concluded The graduated from Waseda University in 1956. In 1961, he received his Ph.D in commerce from Treaty of Peace and Amity between the United States and the same university and began working at the the Empire of Japan followed shortly by peace treaties National Diet Library. Mr. Watanabe worked there as manager of the with various Western countries such as England, The department that researches the law as it th applies to agriculture. He then worked as Netherlands, and Russia. 2004 marks the 150 anniversary manager of the department that researches foreign affairs, and finally he devoted himself to of this opening of Japan’s borders to other nations. research at the Library. Mr. Watanabe retired in 1991 and is now head of a history laboratory researching various The opening of Japan’s borders, along with the restoration aspects of cities, farms and villages. Mr. Watanabe’s major works include Toshi to of political power to the Imperial court, was seen as an Noson no Aida—Toshikinko Nogyo Shiron, 1983, Ronsosha; Kikigaki •Tokyo no Shokuji, opportunity to aggressively integrate Western customs into edited 1987, Nobunkyo; Kyodai Toshi Edo ga Japanese culture. In terms of diet, removal of the long- Washoku wo Tsukutta, 1988, Nobunkyo; Nou no Aru Machizukuri, edited 1989, Gakuyo- standing social taboo against the eating of meat became a shobo; Tokyo ni Nochi ga Atte Naze Warui, collaboration 1991, Gakuyoshobo; Kindai symbol of this integration. -

Volume 16 AJHR 50 Parliament.Pdf

APPENDIX TO THE JOURNALS OF THE House of Representatives OF NEW ZEALAND 2011–2014 VOL. 16 J—PAPERS RELATING TO THE BUSINESS OF THE HOUSE IN THE REIGN OF HER MAJESTY QUEEN ELIZABETH THE SECOND Being the Fiftieth Parliament of New Zealand 0110–3407 WELLINGTON, NEW ZEALAND: Published under the authority of the House of Representatives—2015 ARRANGEMENT OF THE PAPERS _______________ I—Reports and proceedings of select committees VOL. 1 Reports of the Education and Science Committee Reports of the Finance and Expenditure Committee Reports of the Government Administration Committee VOL. 2 Reports of the Health Committee Report of the Justice and Electoral Committee Reports of the Māori Affairs Committee Reports of the Social Services Committee Reports of the Officers of Parliament Committee Reports of the Regulations Review Committee VOL. 3 Reports of the Regulations Review Committee Reports of the Privileges Committee Report of the Standing Orders Committee VOL. 4 Reports of select committees on the 2012/13 Estimates VOL. 5 Reports of select committees on the 2013/14 Estimates VOL. 6 Reports of select committees on the 2014/15 Estimates Reports of select committees on the 2010/11 financial reviews of Government departments, Offices of Parliament, and reports on non-departmental appropriations VOL. 7 Reports of select committees on the 2011/12 financial reviews of Government departments, Offices of Parliament, and reports on non-departmental appropriations Reports of select committees on the 2012/13 financial reviews of Government departments, Offices of Parliament, and reports on non-departmental appropriations VOL. 8 Reports of select committees on the 2010/11 financial reviews of Crown entities, public organisations, and State enterprises VOL.