Complex Use of Land and Water Resources in Luwu, South Sulawesi, Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wellington Park Historic Tracks and Huts Network Comparative Analysis

THE HISTORIC TRACK & HUT NETWORK OF THE HOBART FACE OF MOUNT WELLINGTON Interim Report Comparative Analysis & Significance Assessment Anne McConnell MAY 2012 For the Wellington Park Management Trust, Hobart. Anne D. McConnell Consultant - Cultural Heritage Management, Archaeology & Quaternary Geoscience; GPO Box 234, Hobart, Tasmania, 7001. Background to Report This report presents the comparative analysis and significance assessment findings for the historic track and hut network on the Hobart-face of Mount Wellington as part of the Wellington Park Historic Track & Hut Network Assessment Project. This report is provided as the deliverable for the second milestone for the project. The Wellington Park Historic Track & Hut Network Assessment Project is a project of the Wellington Park Management Trust. The project is funded by a grant from the Tasmanian government Urban Renewal and Heritage Fund (URHF). The project is being undertaken on a consultancy basis by the author, Anne McConnell. The data contained in this assessment will be integrated into the final project report in approximately the same format as presented here. Image above: Holiday Rambles in Tasmania – Ascending Mt Wellington, 1885. [Source – State Library of Victoria] Cover Image: Mount Wellington Map, 1937, VW Hodgman [Source – State Library of Tasmania] i CONTENTS page no 1 BACKGROUND - THE EVOLUTION OF 1 THE TRACK & HUT NETWORK 1.1 The Evolution of the Track Network 1 2.2 The Evolution of the Huts 18 2 A CONTEXT FOR THE TRACK & HUT 29 NETWORK – A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS 2.1 -

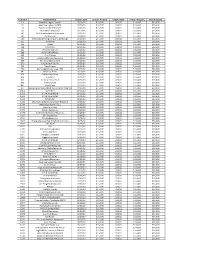

2021-02-09 Final Disbursement Spreadsheet

License # Establishment Check 1 Date Check 1 Amount Check 2 Date Check 2 Amount Total Awarded 51 American Legion Post #1 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 59 American Legion Post #28 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 74 Pancho's Villa Restaurant 11/05/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 83 Asia GarDens/BranDy's 11/19/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 107 Bella Vista Pizzaria & Restaurant 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 140 The Blue Fox 10/29/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 200 Matanuska Brewing ComPany, Anchorage 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 217 Williwaw 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 225 Koots 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 258 Club Paris 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 321 Chili's Bar anD Grill 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 398 Buffalo WilD Wings 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 434 Fiori D'Italia 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 629 La Cabana Mexican Restaurant 11/05/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 635 Serrano's Mexican Grill 11/12/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 670 Long Branch Saloon 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 733 Twin Dragon 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 750 Anchorage Moose LoDge 1534 10/29/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 761 MulDoon Pizza 11/19/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 814 The BraDley House 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 826 Tequila 61 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 842 The New Peanut Farm 10/29/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 888 Pizza OlymPia 12/11/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 891 Pizza Plaza 12/11/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 Anchorage977 Brewing ComPany (NeeD sPecial email if aPPlieD for Tier11/05/20 A) $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 1064 Sorrento's 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 1203 V.F.W. -

Native Genius in Anonymous Architecture

Anno 1778 m # # PHILLIPS ACADEMY # # # OLIVER-WENDELL- HOLMES # # # LIBRARY # # # # Lulie Anderson Fuess Fund The discovery and recording of the “vernacular” architec¬ ture of the Americas was a unique adventure. There were no guide books. Sibyl Moholy-Nagy’s search involved some 15,000 miles of travel between the St. Lawrence River and the Antilles by every conceivable means of transportation. Here in this handsome volume, illustrated with 105 photo¬ graphs and 21 drawings, are some of the amazing examples of architecture—from 1600 on—to be found in the Americas. Everybody concerned with today’s problems of shelter will be fascinated by the masterly solutions of these natural archi¬ tects who settled away from the big cities in search of a us architecture is a fascinating happier, freer, more humane existence. various appeal: Pictorially excit- ly brings native architecture alive is many provocative insights into mericas, their culture, the living and tradition. It explores, for the )f unknown builders in North and litectural heritage. Never before the beautiful buildings—homes, nills and other structures—erected architects by their need for shelter 3 settlers brought a knowledge of irt of their former cultures and their new surroundings that they ures both serviceable and highly art. The genius revealed in the ptation of Old World solutions to sibyl moholy-nagy was born and educated in Dresden, Ger¬ choice of local materials; in com- many. In 1931 she married the noted painter, photographer ationships might well be the envy and stage designer Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. After living in Hol¬ land and England, they settled in Chicago where Moholy- Nagy founded the Institute of Design for which Mrs. -

COMPLETELY COMFORTABLE 5470 Inn Rd

2558 Schillinger Rd. • 219-7761 COFFEE, SMOOTHIES, LUNCH & BEERS. CHUCK’S FISH ($$) 966 Government St.• 408-9001 LAID-BACK EATERY & FISH MARKET 3249 Dauphin St. • 479-2000 5460 Old Shell Rd. • 344-4575 SEAFOOD AND SUSHI BAMBOO 1477 Battleship Pkwy. • 621-8366 FOY SUPERFOODS ($) 551 Dauphin St.• 219-7051 STEAKHOUSE & SUSHI BAR ($$) RIVER SHACK ($-$$) 119 Dauphin St.• 307-8997 SERDA’S COFFEEHOUSE ($) TRADITIONAL JAPANESE WITH HIBACHI GRILLS SEAFOOD, BURGERS & STEAKS COFFEE, LUNCHES, LIVE MUSIC & GELATO CORNER 251 ($-$$) 650 Cody Rd. S • 300-8383 6120 Marina Dr. • Dog River • 443-7318 GULF COAST EXPLOREUM CAFE ($) 3 Royal St. S. • 415-3000 HIGH QUALITY FOOD & DRINKS BANGKOK THAI ($-$$) THE GRAND MARINER ($-$$) HOMEMADE SOUPS & SANDWICHES 1539 US-98 • Daphne • 517-3963 251 Government St • 432-8000 DELICIOUS, TRADITIONAL THAI CUISINE 65 Government St. • 208-6815 28600 US 98 • Daphne • 626-5286 LOCAL SEAFOOD & PRODUCE DAUPHIN’S ($$-$$$) 6036 Rock Point Rd. • 443-7540 $10/PERSON • $$ 10-25/PERSON • $$$ OVER 25/PERSON SHELL FOOD MART ($) 3821 Airport Blvd. • 344-9995 HOOTERS ($) Co. Rd. 49 & U.S. 98• Magnolia Springs HIGH QUALITY FOOD WITH A VIEW 3869 Airport Blvd. • 345-9544 107 St. Francis St/RSA Building • 444-0200 BANZAI JAPANESE THE HARBOR ROOM ($-$$) COMPLETELY COMFORTABLE 5470 Inn Rd. • 661-9117 SIMPLY SWEET ($) RESTAURANT ($$) UNIQUE SEAFOOD 28975 US 98 • Daphne • 625-3910 CUPCAKE BOUTIQUE DUMBWAITER ($$-$$$) TRADITIONAL SUSHI & LUNCH. 64 S. Water St. • 438-4000 9 Du Rhu Dr. Suite 201 ALL SPORTS BAR & GRILL ($) 6207 Cottage Hill Rd. Suite B • 665-3003 312 Schillinger Rd./Ambassador Plaza• 633-9077 3408 Pleasant Valley Rd. • 345-9338 JAMAICAN VIBE ($) 167 Dauphin St. -

Beaches & Holiday Homes Dog-Friendly Directory

South Devon LOVES DOGS A pet-friendly holiday guide from Coast & Country Cottages Alfie Bear visits Salcombe TipsHoliday from advice local from vets, experts bloggers and The National Farmers’ Union The best forBeaches you and your & four-leggedholiday homes friend Dog-friendlyOver 100 eateries, attractionsdirectory and useful contacts SOUTH DEVON LOVES DOGS Welcome I’m Alfie, an English Springer Spaniel… Water obsessed and beach mad! I am always on the road with my human, sniffing out the very best in all things dog-friendly. Being a famous blogger allows me and my best friend Emma to travel around the country, going to prestigious events such as Crufts and staying in luxury properties like Poll Cottage in the heart of Salcombe. Together, Emma and I find our favourite dog-friendly locations, that our followers love to read about. Emma Bearman is a freelance Personally, I love Devon; it is the perfect place for a doggy photographer based in the holiday. With so many beaches to explore, I know I will Warwickshire countryside. have the best adventures. We always have to take a trip to Emma’s photographs of her beloved canine pal ‘Alfie Bear’, East Portlemouth, with miles of sandy beach and endless quickly turned into a full-time swimming. I love stopping at our favourite pub, The Victoria job and fully functioning online Inn, for a bite to eat on the way home. blog with thousands of fans visiting www.alfiebear.com. Alfie Bear Star of dog blog alfiebear.com We know how lucky we are to live and work in this Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty -

Jack Clemo 1916-55: the Rise and Fall of the 'Clay Phoenix'

1 Jack Clemo 1916-55: The Rise and Fall of the ‘Clay Phoenix’ Submitted by Luke Thompson to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English In September 2015 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. 2 Abstract Jack Clemo was a poet, novelist, autobiographer, short story writer and Christian witness, whose life spanned much of the twentieth century (1916- 1994). He composed some of the most extraordinary landscape poetry of the twentieth century, much of it set in his native China Clay mining region around St Austell in Cornwall, where he lived for the majority of his life. Clemo’s upbringing was one of privation and poverty and he was famously deaf and blind for much of his adult life. In spite of Clemo’s popularity as a poet, there has been very little written about him, and his confessional self-interpretation in his autobiographical works has remained unchallenged. This thesis looks at Clemo’s life and writing until the mid-1950s, holding the vast, newly available and (to date) unstudied archive of manuscripts up against the published material and exploring the contrary narratives of progressive disease and literary development and success. -

Pawnee Tribe, Sioux and the Otoe-Missouri Tribe

Plains Indians By Nicole Kotrous Chapter 1 Plains Indians By Nicole Kotrous Chapter 2 Introduction Years and years ago, buffalo and Indians roamed the plains of North America. It could be that those very buffalo and Indians roamed in your backyard! Imagine... it’s a hot summer night, you’re dashing through the seemingly endless prairie grass. Your bow and arrows bouncing against your back, sweat trickling down your forehead. Your cheeks are blotchy red from running. You look up and meet eyes with a brutal, ferocious animal. You draw your bow, and let the arrow go..swoosh! You have hit the animal. You drop to your knees and begin praying to your one and only God, Wakan Tanka. You thank him for once again feeding your family for another lengthy winter. Plains Indians In the years before European settlers came to the United States, Native American tribes lived all across the land. Several tribes lived in what we call the Plains, or the middle portion of the country. I am going to focus on five Plains Indian tribes. These include: the Ponca tribe, the Omaha tribe, the Pawnee tribe, Sioux and the Otoe-Missouri tribe. Some of these Native- American tribes were nomadic hunters. That means that they traveled all year round in search of plants, animals, food, and fresh water. They also traveled to visit and trade with other tribes. When they traded, they traded for stuff they didn’t have. For example they got horses, shells, beads, and stone that was soft enough to carve, and rock that could be chipped into weapon heads, or points. -

TWWHA Wilderness Value Assessment 2015.Pdf

Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Assessment of Wilderness Value Stage 2: Entire TWWHA Martin Hawes & Roger Ling September 2015 TWWHA Wilderness Value Assessment Stage 2: Entire TWWHA Summary Two computer-based methodologies, the National Wilderness Inventory (NWI) methodology and a revised version of this, were used to assess wilderness value across the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area (TWWHA) and contiguous wild areas based on input geodata that was (mostly) current in 2015. The results were used to assess the current status of wilderness across the region and the changes in wilderness value relative to the results of similar studies undertaken in 1995 and 2005. The 2015 results were broadly similar to those obtained in 2005, although substantial losses due to post-2005 roading were observed in several areas, particularly the Counsel River area. Gains in wilderness value due to the closure, downgrading or revegetation of roads and vehicle tracks were observed in the area west of Macquarie Harbour, the middle Hansons River area and the area north of Victoria Pass. Numerous apparent changes (mainly losses) in wilderness value were observed due the inclusion in the 2015 data set of features such as residences and areas of disturbed land that were overlooked in the 2005 analysis. Comparison using the NWI methodology of current wilderness value with the results obtained in 1995 revealed numerous gains and losses, some of which had already been observed in 2005. Substantial gains in wilderness value, mostly due to the closure, downgrading or revegetation of roads and vehicle tracks, were observed in the area southwest of Macquarie Harbour, Moores Valley, Alma Valley, the northern half of the Jane River Track and Little Fisher Valley. -

2019 High Sierra Program for Download

Welcome! Greetings music lovers and WELCOME to the 29th Annual High Sierra Music Festival. What makes High Sierra so special is that everyone truly brings their “A GAME” to High Sierra, the best versions of themselves – starting with the musicians, on down to the staff and production crews, the vendors and volunteers, to the Quincy community and the patrons! It’s such an amazing aggregate of people and passion, and we’re grateful to all for making it happen! We hope you thoroughly enjoy the weekend while practicing self-care. Please stay hydrated! Thanks to our friends at Klean Kanteen, we have filtered drinking water stations conveniently located throughout the fairgrounds and it’s FREE! (check the festival map in the center of this booklet for locations of the Hydration Stations). If you’re an experienced High Sierra festivarian we consider you an ambassador of the festival and one who upholds the high standard that you have helped set with regard to being “kind neighbors and good people.” We thank you for honoring the unwritten FESTIQUETTE code! (See Festival Guidelines towards the back of this booklet for some specific dos and don’ts.) There’s so much to take in at High Sierra besides the four daytime stages and after midnight venues, so go at a pace that suits you, and if you just feel like relaxing at your campsite you can tune in to Grizzly Radio to listen to what’s happening on stage (see this booklet for station frequencies). Nourish yourself with tasty treats from a wide array of food vendors, shop for yourself or a loved at one of our creative crafts vendor booths, take a young one over to the Family Village, enjoy a swim at Pioneer pool out by Shady Grove, recharge with a yoga or Pilates class, or sample some delicious wine and beer at the High Sierra Swirl – our daily late afternoon beer and wine tasting adjacent to the food court in the Tulsa E. -

Vernacular Architecture in Michigan's Upper Peninsula

Making Something Out of Nothing: Vernacular Architecture in Michigan's Upper Peninsula by Mary Hoefferle Scholars studying the Upper Midwest have described many characteristics of cultural life in Michigan's Upper Peninsula, including the region's foodways (Lockwood, 1991; Magnaghi, 1997), ethnic heritage (Loukinen, 1997), relationship between the Yooper dialect and identity (Remlinger, 2006, 2007), traditions of joke and storytelling (Dorson, 1952; Leary, 1991; 2001), and festival art (Hoefferle, 2009). They and other writers (Frimodig, 1983; Zechlin, 2004) generally characterize Yoopers as resourceful, independent, modest, proud people who often use self-parody to laugh at themselves and “to acknowledge who they are and who they are not” (Leary, 2001, p. 248). However, no one has examined how these and other cultural traits materialize in the U. P.'s vernacular architecture, specifically in its shacks and seasonal housing. Therefore, very few people outside the region know about the biographies of the shack builders, their construction processes, their motivations for shack production, the shack's distinct aesthetic qualities, or the social functions hosted in these humble dwellings. Although humble, vernacular architecture merits serious study and has earned at least one serious definition: Brunskill defines vernacular architecture as “a building designed by an amateur without any training in design; the individual will have been guided by a series of conventions built up in his locality, paying little attention to what may be fashionable. The function of the building would be the dominant factor, aesthetic considerations, though present to some small degree, being quite minimal. Local materials would be used as a matter of course, other materials being chosen and imported quite exceptionally” (Brunskill, 2000, pp. -

Irides Fact-Finding Missions to Philippines”

Second Report International Research Institute of Disaster Science (IRIDeS) 14 March 2015 “IRIDeS Fact-finding missions to Philippines” TOHOKU University 2015 ii iii iv FOREWORD At 4:40 AM on November 8, 2013, Super Typhoon Yolanda made first landfall over Guiuan, Eastern Samar and caused immediate destruction in wide area of central Philippines. Over the course of a few hours, it massive damages, with more than 6,000 individuals reported dead and thousands more accounted missing in the aftermath of remarkably strong winds, storm surge and large waves induced by the tropical cyclone. As early as three days before landfall, the Philippine government made necessary preparations of the historic super typhoon. Assessing forecasts from various numerical models, the Philippine Atmospheric Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA), one of the attached agencies of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) under its Scientific and Technical Services Institutes, officially issued Weather Advisory #1 for Tropical Cyclone Yolanda (Haiyan) at 11:00 AM of November 5 to serve as a public warning for the imminent danger. Two days after, on November 7, the Weather Bureau issued Severe Weather Bulletin #3, raising the alarm and informing the public that storm surges may reach up to seven meters in wave height along the coastal areas of Samar, Leyte, Biliran, Bantayan and Camotes islands, Northern Cebu -- including Cebu City and Bohol. However, in spite of the efforts of the government to reduce and mitigate the disaster’s effects, Yolanda still caused widespread destruction and an alarming number of casualties in the Philippines. Because of this, PAGASA has taken a proactive approach to prepare for future occurrences of such devastating tropical cyclones. -

Inside Austronesian Houses: Perspectives on Domestic Designs for Living

InsIde AustronesIAn Houses PersPectives on domestic designs for living InsIde AustronesIAn Houses PersPectives on domestic designs for living edited by James J. fox A publication of the department of Anthropology as part of the comparative Austronesian Project, research school of Pacific studies the Australian national University canberra ACT Australia Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Previously published in Australia by the Department of Anthropology in association with the Comparative Austronesian Project, Research School of Pacific Studies, The Australian National University, Canberra 1993. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Inside Austronesian Houses Bibliography. ISBN 0 731515 95 1 (print) ISBN 1 920942 84 X (online) 1. Dwellings - Asia, Southeastern. 2. Dwellings - Oceania. 3. Asia, Southeastern - Social life and customs. 4. Oceania - Social life and customs. I. Fox, James J., 1940- . II. Australian National University. Dept. of Anthropology. III. Comparative Austronesian Project. 392.360095 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Typesetting and drawings by Margaret Tyrie Cover design by Adrian Young Printed at ANU Printing Service, Canberra © The several authors, each in respect of the paper presented, 1993 This edition © 2006 ANU E Press DEDICATED TO THE MEMORIES OF: Anthony Forge and Hedda Morrison Building a new longhouse (photo by Hedda Morrison) Inside Austronesian Houses Table of Contents Acknowledgements xi Chapter 1.