University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Payatas Landfill Gas to Energy Project in the Philippines

Project Design Document for PNOC EC Payatas Landfill Gas to Energy Project in the Philippines March 2004 Mitsubishi Securities Clean Energy Finance Committee 1 CONTENTS A. General Description of Project Activity 3 B. Baseline Methodology 12 C. Duration of the Project Activity / Crediting Period 23 D. Monitoring Methodology and Plan 24 E. Calculation of GHG Emissions by Sources 29 F. Environmental Impacts 35 G. Stakeholders Comments 36 Annexes Annex 1: Information on Participants in the Project Activity 37 Annex 2: Information Regarding Public Funding 39 Annex 3: New Baseline Methodology 40 Annex 4: New Monitoring Methodology 41 Annex 5: Baseline Data 42 Appendices Appendix 1: Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000 42 Appendix 2: Philippine Clean Air Act of 1999 52 Appendix 3: Philippine National Air Standards 54 Appendix 4: Calculation for Methane Used for Electricity Generation & Flaring 60 Appendix 5: Methane Used for Electricity Generation 62 Appendix 6: Details of Electricity Baseline and its Development 63 Appendix 7: Public Participation 66 2 A. GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF PROJECT ACTIVITY A.1 Title of the project activity PNOC Exploration Corporation (PNOC EC) Payatas Landfill Gas to Energy Project in the Philippines (the Project or the Project Activity) A.2 Description of the project activity The Project will utilize landfill gas (LFG), recovered from the Payatas dumpsite in Quezon City in the Philippines, for electricity generation. PNOC EC will install a gas extraction and collection system and build a 1 MW power plant in Payatas. The electricity generated by the Project will be sold to the Manila Electric Company (MERALCO), which services Metro Manila and is also the country’s largest utility company. -

FOI Manuals/Receiving Officers Database

National Government Agencies (NGAs) Name of FOI Receiving Officer and Acronym Agency Office/Unit/Department Address Telephone nos. Email Address FOI Manuals Link Designation G/F DA Bldg. Agriculture and Fisheries 9204080 [email protected] Central Office Information Division (AFID), Elliptical Cheryl C. Suarez (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 2158 [email protected] Road, Diliman, Quezon City [email protected] CAR BPI Complex, Guisad, Baguio City Robert L. Domoguen (074) 422-5795 [email protected] [email protected] (072) 242-1045 888-0341 [email protected] Regional Field Unit I San Fernando City, La Union Gloria C. Parong (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4111 [email protected] (078) 304-0562 [email protected] Regional Field Unit II Tuguegarao City, Cagayan Hector U. Tabbun (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4209 [email protected] [email protected] Berzon Bldg., San Fernando City, (045) 961-1209 961-3472 Regional Field Unit III Felicito B. Espiritu Jr. [email protected] Pampanga (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4309 [email protected] BPI Compound, Visayas Ave., Diliman, (632) 928-6485 [email protected] Regional Field Unit IVA Patria T. Bulanhagui Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4429 [email protected] Agricultural Training Institute (ATI) Bldg., (632) 920-2044 Regional Field Unit MIMAROPA Clariza M. San Felipe [email protected] Diliman, Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4408 (054) 475-5113 [email protected] Regional Field Unit V San Agustin, Pili, Camarines Sur Emily B. Bordado (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4505 [email protected] (033) 337-9092 [email protected] Regional Field Unit VI Port San Pedro, Iloilo City Juvy S. -

UN-HABITAT Housing Unit - Housing and Slum Upgrading Branch, UN-Habitat, Nairobi, Kenya

DRAFT Suggestions and comments received by UN-HABITAT Housing Unit - Housing and Slum Upgrading Branch, UN-Habitat, Nairobi, Kenya 1 DRAFT Guidelines for the implementation of the right to adequate housing Special Rapporteur on the right to adequate housing, Ms. Leilani Farha Draft for Consultation Deadline for written comments: 18 November 2019 Table of Contents I. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 3 Deleted: 2 II. Guidelines for the implementation of the right to adequate housing ........................................... 5 Deleted: 4 Guideline No. 1 ................................................................................................................................... 5 Deleted: 4 Recognize the right to housing as a fundamental human right in national law and practice ........ 5 Deleted: 4 Guideline No. 2 ................................................................................................................................... 7 Deleted: 5 Design, implement and regularly monitor comprehensive strategies for the realization of the right to housing ............................................................................................................................... 7 Deleted: 5 Guideline No. 3 ................................................................................................................................... 8 Deleted: 7 Ensure the progressive realization of the right to adequate -

Housing Policy in Developing Countries

1 HOUSING POLICY IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES THE IMPORTANCE OF THE INFORMAL ECONOMY Richard Arnott* January 21, 2008 Abstract: All countries have a formal economy and an informal economy. But, on average, in developing countries the relative size of the informal sector is considerably larger than in developed countries. This paper argues that this has important implications for housing policy in developing countries. That most poor households derive their income from informal employment effectively precludes income-contingent transfers as a method of redistribution. Also, holding fixed real economic activity, the larger is the relative size of the informal sector, the lower is fiscal capacity, and the more distortionary is government provision of a given level of goods and services, which restricts the desirable scale and scope of government policy. For the same reasons, housing policies that have proven successful in developed countries may not be successful when employed in developing countries. Please do not cite or quote without the permission of the author. *Department of Economics University of California, Riverside Riverside, CA 92521 951-827-1581 [email protected] 2 Housing Policy in Developing Countries The Importance of the Informal Economy1 1. Introduction In the foreword to The Challenge of Slums (2003), published by the United Nations Settlements Programme, Kofi Annan wrote: Almost 1 billion, or 32 percent of the world’s urban population, live in slums, the majority of them in the developing world. Moreover, the locus of global poverty is moving to the cities, a process now recognized as the ‘urbanization of poverty’. Without concerted action on the part of municipal authorities, national governments, civil society actors and the international community, the number of slum dwellers is likely to increase in most developing countries. -

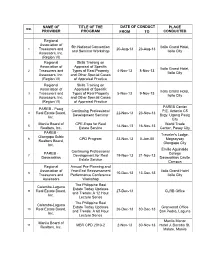

REAL.ESTATE Cpdprogram.Pdf

NAME OF TITLE OF THE DATE OF CONDUCT PLACE NO. PROVIDER PROGRAM FROM TO CONDUCTED Regional Association of 5th National Convention Iloilo Grand Hotel, 1 Treasurers and 20-Aug-13 23-Aug-13 and Seminar Workshop Iloilo City Assessors, Inc. (Region VI) Regional Skills Training on Association of Appraisal of Specific Iloilo Grand Hotel, 2 Treasurers and Types of Real Property 4-Nov-13 8-Nov-13 Iloilo City Assessors, Inc. and Other Special Cases (Region VI) of Appraisal Practice Regional Skills Training on Association of Appraisal of Specific Iloilo Grand Hotel, 3 Treasurers and Types of Real Property 5-Nov-13 9-Nov-13 Iloilo City Assessors, Inc. and Other Special Cases (Region VI) of Appraisal Practice PAREB Center PAREB - Pasig Continuing Professional P.E. Antonio C5 4 Real Estate Board, 22-Nov-13 23-Nov-13 Development Seminar Brgy. Ugong Pasig Inc. City Manila Board of CPE-Expo for Real World Trade 5 14-Nov-13 16-Nov-13 Realtors, Inc. Estate Service Center, Pasay City PAREB - Traveler's Lodge, Olongapo Subic 6 CPD Program 23-Nov-13 0-Jan-00 Magsaysay Realtors Board, Olongapo City Inc. Emilio Aguinaldo Continuing Professional PAREB - College 7 Development for Real 19-Nov-13 21-Nov-13 Dasmariñas Dasmariñas Cavite Estate Service Campus Regional Annual Pre-Planning and Association of Year-End Reassessment Iloilo Grand Hotel 8 10-Dec-13 13-Dec-13 Treasurers and Performance Conference Iloilo City Assessors Workshop The Philippine Real Calamba-Laguna Estate Today Updates 9 Real Estate Board, 27-Dec-13 CLRB Office and Trends: A 12 Hour Inc. -

Housing Policy in Developing Countries the Importance

1 HOUSING POLICY IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES THE IMPORTANCE OF THE INFORMAL ECONOMY Richard Arnott* March 9, 2008 Abstract: All countries have a formal economy and an informal economy. But, on average, in developing countries the relative size of the informal sector is considerably larger than in developed countries. This paper argues that this has important implications for housing policy in developing countries. That most poor households derive their income from informal employment effectively precludes income-contingent transfers as a method of redistribution. Also, holding fixed real economic activity, the larger is the relative size of the informal sector, the lower is fiscal capacity, and the more distortionary is government provision of a given level of goods and services, which restricts the desirable scale and scope of government policy. For the same reasons, housing policies that have proven successful in developed countries may not be successful when employed in developing countries. Please do not cite or quote without the permission of the author. *Department of Economics University of California, Riverside Riverside, CA 92521 951-827-1581 [email protected] 2 Housing Policy in Developing Countries The Importance of the Informal Economy1 1. Introduction In the foreword to The Challenge of Slums (2003), published by the United Nations Settlements Programme, Kofi Annan wrote: Almost 1 billion, or 32 percent of the world‟s urban population, live in slums, the majority of them in the developing world. Moreover, the locus of global poverty is moving to the cities, a process now recognized as the „urbanization of poverty‟. Without concerted action on the part of municipal authorities, national governments, civil society actors and the international community, the number of slum dwellers is likely to increase in most developing countries. -

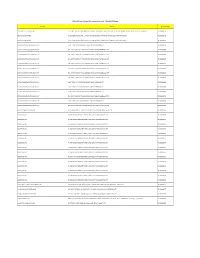

DOLE-NCR for Release AEP Transactions As of 7-16-2020 12.05Pm

DOLE-NCR For Release AEP Transactions as of 7-16-2020 12.05pm Company Address Transaction No. 3M SERVICE CENTER APAC, INC. 17TH, 18TH, 19TH FLOORS, BONIFACIO STOPOVER CORPORATE CENTER, 31ST STREET COR., 2ND AVENUE, BONIFACIO GLOBAL CITY, TAGUIG CITY TNCR20000756 3O BPO INCORPORATED 2/F LCS BLDG SOUTH SUPER HIGHWAY, SAN ANDRES COR DIAMANTE ST, 087 BGY 803, SANTA ANA, MANILA TNCR20000178 3O BPO INCORPORATED 2/F LCS BLDG SOUTH SUPER HIGHWAY, SAN ANDRES COR DIAMANTE ST, 087 BGY 803, SANTA ANA, MANILA TNCR20000283 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5-10/F TOWER 1, PITX KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000536 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000554 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000569 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000607 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000617 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000632 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000633 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000638 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5-10/F TOWER 1, PITX KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000680 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5-10/F TOWER 1, PITX KENNEDY -

Urban Fragmentation and Class Contention in Metro Manila

Urban Fragmentation and Class Contention in Metro Manila by Marco Z. Garrido A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Professor Jeffery M. Paige, Chair Dean Filomeno V. Aguilar, Jr., Ateneo de Manila University Associate Professor Allen D. Hicken Professor Howard A. Kimeldorf Associate Professor Frederick F. Wherry, Columbia University Associate Professor Gavin M. Shatkin, Northeastern University © Marco Z. Garrido 2013 To MMATCG ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my informants in the slums and gated subdivisions of Metro Manila for taking the time to tell me about their lives. I have written this dissertation in honor of their experiences. They may disagree with my analysis, but I pray they accept the fidelity of my descriptions. I thank my committee—Jeff Paige, Howard Kimeldorf, Gavin Shatkin, Fred Wherry, Jun Aguilar, and Allen Hicken—for their help in navigating the dark woods of my dissertation. They served as guiding lights throughout. In gratitude, I vow to emulate their dedication to me with respect to my own students. I thank Nene, the Cayton family, and Tito Jun Santillana for their help with my fieldwork; Cynch Bautista for rounding up an academic audience to suffer through a presentation of my early ideas, Michael Pinches for his valuable comments on my prospectus, and Jing Karaos for allowing me to affiliate with the Institute on Church and Social Issues. I am in their debt. Thanks too to Austin Kozlowski, Sahana Rajan, and the Spatial and Numeric Data Library at the University of Michigan for helping me make my maps. -

Assessing the Effect of a Dumpsite to Groundwater Quality in Payatas, Philippines

American Journal of Environmental Sciences 4 (4): 276-280, 2008 ISSN 1553-345X © 2008 Science Publications Assessing the Effect of a Dumpsite to Groundwater Quality in Payatas, Philippines Glenn L. Sia Su Department of Biology, De La Salle University, Taft, Manila, Philippines Abstract: The study assessed and compared the groundwater quality of 14 selected wells continuously used in the with (Payatas) and without dumpsite (Holy Spirit) areas at the Payatas estate, Philippines. Water quality monitoring and analyses of the bio-physico-chemical variables (pH, Total Suspended Solids (TSS), Total Dissolved Solids (TDS), total coliform, conductivity, salinity, nitrate-nitrogen, sulfate, color, total chromium, total lead and total cadmium) were carried out for six consecutive months, from April to September 2003, covering both dry and wet seasons. Results showed most of the groundwater quality variables in both the with and without dumpsite areas of the Payatas estate were within the normal Philippine water quality standards except for the observed high levels of TDS, TSS and total coliform and low pH levels. No significant differences were observed for nitrate- nitrogen, total cadmium, total lead, total chromium and total coliform in both the with and without dumpsite areas. TDS, conductivity, salinity and sulfate concentrations in the with dumpsite groundwater sources were significantly different compared to those in the without dumpsite areas. Continuous water quality monitoring is encouraged to effectively analyze the impact of dumpsites on the environment and human health. Key words: Water quality, environmental assessment INTRODUCTION concerns that the Novaliches Reservoir is now contaminated with toxic substances beyond safe The 15-ha Payatas open dumpsite is within the concentrations. -

The July 10 2000 Payatas Landfill Slope Failure

The July 10 2000 Payatas Landfill Slope Failure Navid H. Jafari, Doctoral Candidate, Dept. of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Illinois Urbana- Champaign, Urbana, IL, 61801, USA; email: [email protected] Timothy D. Stark, Professor, Dept. of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Illinois Urbana- Champaign, Urbana, IL, 61801, USA; email: [email protected] Scott Merry, Associate Professor, Dept. of Civil Engineering, University of the Pacific, Stockton, CA, 95211, USA; email: [email protected] ABSTRACT: This paper presents an investigation of the slope failure in the Payatas landfill in Quezon City, Philippines. This failure, which killed at least 330 persons, occurred July 10th 2000 after two weeks of heavy rain from two typhoons. Slope stability analyses indicate that the raised leachate level, existence of landfill gas created by natural aerobic and anaerobic degradation, and a significantly over-steepened slope contributed to the slope failure. The Hydrologic Evaluation of Landfill Performance (HELP) model was used to predict the location of the leachate level in the waste at the time of the slope failure for analysis purposes. This paper presents a description of the geological and environmental conditions, identification of the critical failure surface, and slope stability analyses to better understand the failure and present recommendations for other landfills in tropical areas. In addition, this case history is used to evaluate uncertainty in parameters used in back-analysis of a landfill slope failure. KEYWORDS: Landfills, Failure investigations, Slope stability, Shear strength, Gas formation, Leachate, Leachate recirculation, Pore pressures. SITE LOCATION: IJGCH-database.kmz (requires Google Earth) INTRODUCTION At approximately 4:30 am Manila local time (MLT) on July 10th 2000, a slope failure occurred in the Payatas Landfill in Quezon City, Philippines. -

Wellington Park Historic Tracks and Huts Network Comparative Analysis

THE HISTORIC TRACK & HUT NETWORK OF THE HOBART FACE OF MOUNT WELLINGTON Interim Report Comparative Analysis & Significance Assessment Anne McConnell MAY 2012 For the Wellington Park Management Trust, Hobart. Anne D. McConnell Consultant - Cultural Heritage Management, Archaeology & Quaternary Geoscience; GPO Box 234, Hobart, Tasmania, 7001. Background to Report This report presents the comparative analysis and significance assessment findings for the historic track and hut network on the Hobart-face of Mount Wellington as part of the Wellington Park Historic Track & Hut Network Assessment Project. This report is provided as the deliverable for the second milestone for the project. The Wellington Park Historic Track & Hut Network Assessment Project is a project of the Wellington Park Management Trust. The project is funded by a grant from the Tasmanian government Urban Renewal and Heritage Fund (URHF). The project is being undertaken on a consultancy basis by the author, Anne McConnell. The data contained in this assessment will be integrated into the final project report in approximately the same format as presented here. Image above: Holiday Rambles in Tasmania – Ascending Mt Wellington, 1885. [Source – State Library of Victoria] Cover Image: Mount Wellington Map, 1937, VW Hodgman [Source – State Library of Tasmania] i CONTENTS page no 1 BACKGROUND - THE EVOLUTION OF 1 THE TRACK & HUT NETWORK 1.1 The Evolution of the Track Network 1 2.2 The Evolution of the Huts 18 2 A CONTEXT FOR THE TRACK & HUT 29 NETWORK – A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS 2.1 -

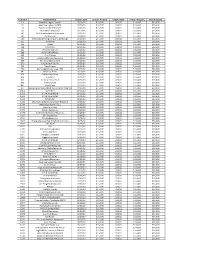

2021-02-09 Final Disbursement Spreadsheet

License # Establishment Check 1 Date Check 1 Amount Check 2 Date Check 2 Amount Total Awarded 51 American Legion Post #1 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 59 American Legion Post #28 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 74 Pancho's Villa Restaurant 11/05/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 83 Asia GarDens/BranDy's 11/19/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 107 Bella Vista Pizzaria & Restaurant 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 140 The Blue Fox 10/29/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 200 Matanuska Brewing ComPany, Anchorage 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 217 Williwaw 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 225 Koots 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 258 Club Paris 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 321 Chili's Bar anD Grill 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 398 Buffalo WilD Wings 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 434 Fiori D'Italia 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 629 La Cabana Mexican Restaurant 11/05/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 635 Serrano's Mexican Grill 11/12/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 670 Long Branch Saloon 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 733 Twin Dragon 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 750 Anchorage Moose LoDge 1534 10/29/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 761 MulDoon Pizza 11/19/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 814 The BraDley House 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 826 Tequila 61 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 842 The New Peanut Farm 10/29/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 888 Pizza OlymPia 12/11/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 891 Pizza Plaza 12/11/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 Anchorage977 Brewing ComPany (NeeD sPecial email if aPPlieD for Tier11/05/20 A) $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 1064 Sorrento's 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 1203 V.F.W.