The Quintessence of Ibsenism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ohio Graduation Tests

---~ Department of Education Student Name OHIO GRADUATION TESTS Reading Spring 2008 This test was originally administered to students in March 2008. This publicly released material is appropriate for use by Ohio teachers in instructional settings. This test is aligned with Ohio’s Academic Content Standards. © 2008 by Ohio Department of Education The Ohio Department of Education does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, or disability in employment or the provision of services. The Ohio Department of Education acknowledges that copyrighted material may contain information that is not currently accurate and assumes no responsibility for material reproduced in this document that reflects such inaccuracies. Form A Reading READING TEST Directions: Each passage in this test is followed by several questions. After reading the passage, choose the correct answer for each multiple-choice question, and then mark the corresponding circle in the Answer Document. If you change an answer, be sure to erase the first mark completely. For the written-response questions, answer completely in the Answer Document in the space provided. You may not need to use the entire space provided. You may refer to the passages as often as necessary. Make sure the number of the question in this test booklet corresponds to the number on the Answer Document. Be sure all your answers are complete and appear in the Answer Document. The Sweat-Soaked Life of a Glamorous Rockette by Susan Dominus 1 One after the other, like beautiful, glittering drones, the Rockettes spilled off an elevator onto the stage level at Radio City Music Hall. -

Festival 30000 LP SERIES 1961-1989

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS FESTIVAL 30,000 LP SERIES 1961-1989 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER AUGUST 2020 Festival 30,000 LP series FESTIVAL LP LABEL ABBREVIATIONS, 1961 TO 1973 AML, SAML, SML, SAM A&M SINL INFINITY SODL A&M - ODE SITFL INTERFUSION SASL A&M - SUSSEX SIVL INVICTUS SARL AMARET SIL ISLAND ML, SML AMPAR, ABC PARAMOUNT, KL KOMMOTION GRAND AWARD LL LEEDON SAT, SATAL ATA SLHL LEE HAZLEWOOD INTERNATIONAL AL, SAL ATLANTIC LYL, SLYL, SLY LIBERTY SAVL AVCO EMBASSY DL LINDA LEE SBNL BANNER SML, SMML METROMEDIA BCL, SBCL BARCLAY PL, SPL MONUMENT BBC BBC MRL MUSHROOM SBTL BLUE THUMB SPGL PAGE ONE BL BRUNSWICK PML, SPML PARAMOUNT CBYL, SCBYL CARNABY SPFL PENNY FARTHING SCHL CHART PJL, SPJL PROJECT 3 SCYL CHRYSALIS RGL REG GRUNDY MCL CLARION RL REX NDL, SNDL, SNC COMMAND JL, SJL SCEPTER SCUL COMMONWEALTH UNITED SKL STAX CML, CML, CMC CONCERT-DISC SBL STEADY CL, SCL CORAL NL, SNL SUN DDL, SDDL DAFFODIL QL, SQL SUNSHINE SDJL DJM EL, SEL SPIN ZL, SZL DOT TRL, STRL TOP RANK DML, SDML DU MONDE TAL, STAL TRANSATLANTIC SDRL DURIUM TL, STL 20TH CENTURY-FOX EL EMBER UAL, SUAL, SUL UNITED ARTISTS EC, SEC, EL, SEL EVEREST SVHL VIOLETS HOLIDAY SFYL FANTASY VL VOCALION DL, SDL FESTIVAL SVL VOGUE FC FESTIVAL APL VOX FL, SFL FESTIVAL WA WALLIS GNPL, SGNPL GNP CRESCENDO APC, WC, SWC WESTMINSTER HVL, SHVL HISPAVOX SWWL WHITE WHALE SHWL HOT WAX IRL, SIRL IMPERIAL IL IMPULSE 2 Festival 30,000 LP series FL 30,001 THE BEST OF THE TRAPP FAMILY SINGERS, RECORD 1 TRAPP FAMILY SINGERS FL 30,002 THE BEST OF THE TRAPP FAMILY SINGERS, RECORD 2 TRAPP FAMILY SINGERS SFL 930,003 BRAZAN BRASS HENRY JEROME ORCHESTRA SEC 930,004 THE LITTLE TRAIN OF THE CAIPIRA LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SFL 930,005 CONCERTO FLAMENCO VINCENTE GOMEZ SFL 930,006 IRISH SING-ALONG BILL SHEPHERD SINGERS FL 30,007 FACE TO FACE, RECORD 1 INTERVIEWS BY PETE MARTIN FL 30,008 FACE TO FACE, RECORD 2 INTERVIEWS BY PETE MARTIN SCL 930,009 LIBERACE AT THE PALLADIUM LIBERACE RL 30,010 RENDEZVOUS WITH NOELINE BATLEY AUS NOELEEN BATLEY 6.61 30,011 30,012 RL 30,013 MORIAH COLLEGE JUNIOR CHOIR AUS ARR. -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

Light Horses : Breeds and Management

' K>\.K>. > . .'.>.-\ j . ; .>.>.-.>>. ' UiV , >V>V >'>>>'; ) ''. , / 4 '''. 5 : , J - . ,>,',> 1 , .\ '.>^ .\ vV'.\ '>»>!> ;;••!>>>: .>. >. v-\':-\>. >*>*>. , > > > > , > > > > > > , >' > > >»» > >V> > >'» > > > > > > . »v>v - . : . 9 '< TUFTS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES 3 9090 014 661 80 r Family Libra;-, c veterinary Medium f)HBnf"y Schoo Ve' narv Medicine^ Tu iiv 200 Wesuc . ,-<oao Nerth Graft™ MA 01538 kXsf*i : LIVE STOCK HANDBOOKS. Edited by James Sinclair, Editor of "Live Stock Journal" "Agricultural Gazette" &c. No. II. LIGHT HORSES. BREEDS AND MANAGEMENT BY W. C. A. BLEW, M.A, ; WILLIAM SCARTH DIXON ; Dr. GEORGE FLEMING, C.B., F.R.C.V.S. ; VERO SHAW, B.A. ; ETC. SIZKZTJBI ZEiZDITIOILT, le-IEJ-VISIEID. ILLUSTRATED. XonDon VINTON & COMPANY, Ltd., 8, BREAM'S BUILDINGS, CHANCERY LANE, E.C. 1919. —— l°l LIVE STOCK HANDBOOKS SERIES. THE STOCKBREEDER'S LIBRARY. Demy 8vo, 5s. net each, by post, 5s. 6d., or the set of five vols., if ordered direct from the Publisher, carriage free, 25s. net; Foreign 27s. 6d. This series covers the whole field of our British varieties of Horses, Cattle, Sheep and Pigs, and forms a thoroughly practical guide to the Breeds and Management. Each volume is complete in itself, and can be ordered separately. I. —SHEEP: Breeds and Management. New and revised 8th Edition. 48 Illustrations. By John Wrightson, M.R.A.C., F.C.S., President of the College of Agriculture, Downton. Contents. —Effects of Domestication—Long and Fine-woolled Sheep—British Long-woolled Sheep—Border Leicesters—Cotswolds—Middle-woolled—Mountain or Forest—Apparent Diff- erences in Breeds—Management—Lambing Time— Ordinary and Extraordinary Treatment of Lambs—Single and Twin Lambs—Winter Feeding—Exhibition Sheep—Future of Sheep Farm- ing—A Large Flock—Diseases. -

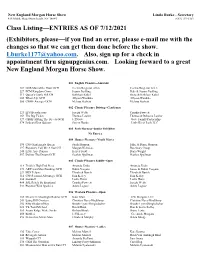

Class Listing—ENTRIES AS of 7/12/2021 (Exhibitors, Please—If You Find an Error, Please E-Mail Me with the Changes So That We Can Get Them Done Before the Show

New England Morgan Horse Show Linda Burke - Secretary 435 Middle Road Horseheads, NY 14845 (607) 739-6169 Class Listing—ENTRIES AS OF 7/12/2021 (Exhibitors, please—if you find an error, please e-mail me with the changes so that we can get them done before the show. [email protected]. Also, sign up for a check in appointment thru signupgenius.com. Looking forward to a great New England Morgan Horse Show. 001 English Pleasure--Amateur 102 GLB Man of the Hour GCH Cecilia Bergeron Allen Cecilia Bergeron Allen 227 FCM Kingdom Come Jeanne Fuelling Dale & Jeanne Fuelling 311 Queen's Castle Hill CH Kathleen Kabel Steve & Kathleen Kabel 380 What's Up GCH Allyson Wandtke Allyson Wandtke 566 CBMF Avenger GCH Melissa Beckett Melissa Beckett 002 Classic Pleasure Driving--Gentlemen 123 LPS Beaudacious Joseph Webb Cynthia Fawcett 169 The Big Ticket Thomas Lawlor Thomas & Rebecca Lawlor 327 CBMF Hitting The Streets GCH Jeff Gove Gove Family Partnership 574 Ledyard Don Quixote Steven Handy Little Bit of Luck LLC 003 Park Harness--Junior Exhibitor No Entries 004 Hunter Pleasure--Youth Mares 190 CFS Gentlemen's Queen Sarah Munson Mike & Diane Munson 197 Playmor's Call Me A Star CH Morgan Nicholas Rosemary Croop 248 Little Acre Dancia Kelsey Scott Darla Wright 507 Deliver The Dream GCH Scarlett Spellman Scarlett Spellman 005 Classic Pleasure Saddle--Open 118 Treble's High End Piece Amanda Zsido Amanda Zsido 173 ADC Last Man Standing GCH Robin Vergato James & Robin Vergato 229 MJS Eclipse Elizabeth Burick Elizabeth Burick 314 CFF Personal Advantage GCH -

Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21St Century Chicago

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 Sacred Freedom: Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21St Century Chicago Adam Zanolini The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1617 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SACRED FREEDOM: SUSTAINING AFROCENTRIC SPIRITUAL JAZZ IN 21ST CENTURY CHICAGO by ADAM ZANOLINI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 ADAM ZANOLINI All Rights Reserved ii Sacred Freedom: Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21st Century Chicago by Adam Zanolini This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _________________ __________________________________________ DATE David Grubbs Chair of Examining Committee _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Jeffrey Taylor _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Fred Moten _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Michele Wallace iii ABSTRACT Sacred Freedom: Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21st Century Chicago by Adam Zanolini Advisor: Jeffrey Taylor This dissertation explores the historical and ideological headwaters of a certain form of Great Black Music that I call Afrocentric spiritual jazz in Chicago. However, that label is quickly expended as the work begins by examining the resistance of these Black musicians to any label. -

The Evolution of Yeats's Dance Imagery

THE EVOLUTION OF YEATS’S DANCE IMAGERY: THE BODY, GENDER, AND NATIONALISM Deng-Huei Lee, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2003 APPROVED: David Holdeman, Major Professor Peter Shillingsburg, Committee Member Scott Simpkins, Committee Member Brenda Sims, Chair of Graduate Studies in English James Tanner, Chair of the Department of English C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Lee, Deng-Huei, The Evolution of Yeats’s Dance Imagery: The Body, Gender, and Nationalism. Doctor of Philosophy (British Literature), August 2003, 168 pp., 6 illustrations, 147 titles. Tracing the development of his dance imagery, this dissertation argues that Yeats’s collaborations with various early modern dancers influenced his conceptions of the body, gender, and Irish nationalism. The critical tendency to read Yeats’s dance emblems in light of symbolist- decadent portrayals of Salome has led to exaggerated charges of misogyny, and to neglect of these emblems’ relationship to the poet’s nationalism. Drawing on body criticism, dance theory, and postcolonialism, this project rereads the politics that underpin Yeats’s idea of the dance, calling attention to its evolution and to the heterogeneity of its manifestations in both written texts and dramatic performances. While the dancer of Yeats’s texts follow the dictates of male-authored scripts, those in actual performances of his works acquired more agency by shaping choreography. In addition to working directly with Michio Ito and Ninette de Valois, Yeats indirectly collaborated with such trailblazers of early modern dance as Loie Fuller, Isadora Duncan, Maud Allan, and Ruth St. -

Through the Language Glass: Why the World Looks Different in Other Languages / Guy Deutscher.-Lst Ed

THROUGH the LANGUAGE GLASS Why the World Looks Different in Other Languages GUY DEUTSCHER METROPOL ITAN BOOKS HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY NEW YORK Metropolitan Books Henry Holt and Company, LLC Publishers since 1866 175 Fifth Av enue New York, New York 10010 www.henryholt.com Metropolitan Book!'and 1iiJ0are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLe. Copyright © 2010 by Guy Deutscher All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Deutscher, Guy. Through the language glass: why the world looks different in other languages / Guy Deutscher.-lst ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0c8050-8195-4 1. Comparative linguistics. 2. Historical linguistics. 3. Language and languages in literature. I. Title. P140.D487 201O 41O-dc22 2010001042 Henry Holt books are available for special promotions and premiums. For details contact: Director, Special Markets. First Edition 2010 Designed by Kelly Too Printed in the United States of America 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 CONTENTS PROLOGUE: Language, Culture, and Thought 1 PART I: THE LANGUAGE MIRROR 1. Naming the Rainbow 25 2. A Long-Wave Herring 41 3. The Rude Populations Inhabiting Foreign Lands 58 4. Those Who Said Our Things Before Us 79 5. Plato and the Macedonian Swineherd 99 PART II: THE LANGUAGE LENS 6. Crying Whorf 129 7· Where the Sun Doesn't Rise in the East 157 8. Sex and Syntax 194 9· Russian Blues 217 EPILOGUE: Forgive Us Our Ignorances 233 APPENDIX: Color: In the Eye of the Beholder 241 Notes 251 Bibliography 274 Acknowledgments 293 Illustration Credits 294 Index 295 THROUGH the LANGUAGE GLASS PROLOGUE Language, Culture, and Thought "There are four tongues worthy of the world's use," says the Talmud: "Greek for song, Latin for war, Syriac for lamentation, and Hebrew for ordinary speech." Other authorities have been no less decided in their judgment on what different languages are good fo r. -

8 Can a Fujiyama Mama Be the Female Elvis?

8 CAN A FUJIYAMA MAMA BE THE FEMALE ELVIS? The wild, wild women of rockabilly David Sanjek I don't want a headstone for my grave. I want a fucking monument! (Jerry Lee Lewis) 1 You see, I was always a well-endowed girl, and the guys used to tell me that they didn't know how to fit a 42 into a 331!3. (Sun Records artist Barbara Pittman ) 2 Female artists just don't really sell. (Capital Records producer Ken Nelson) 3 In the opening scene of the 199 3 film True Romance (directed by Tony Scott from a script by Quentin Tarantino), Clarence Worly (Christian Slater) perches on a stool in an anonymous, rundown bar. Addressing his com ments to no one in particular, he soliloquises about 'the King'. Simply put, he asserts, in Jailhouse Rock (19 5 7), Elvis embodied everything that rocka billy is about. 'I mean', he states, 'he is rockabilly. Mean, surly, nasty, rude. In that movie he couldn't give a fuck about nothin' except rockin' and rollin' and livin' fast and dyin' young and leavin' a good lookin' corpse, you know.' As he continues, Clarence's admiration for Elvis transcends mere identification with the performer's public image. He adds, 'Man, Elvis looked good. Yeah, I ain't no fag, but Elvis, he was prettier than most women, most women.' He now acknowledges the presence on the barstool next to him of a blank-faced, blonde young woman. Unconcerned that his overheard thoughts might have disturbed her, he continues, 'I always said if I had to fuck a guy - had to if my life depended on it - I'd 137 DAVID SANJEK THE WILD,~ WOMEN OF ROCK~BILLY fuck Elvis.' The woman concurs with his desire to copulate with 'the and Roll; rockabilly, he writes, 'suggested a young white man celebrating King', but adds, 'Well, when he was alive, not now.' freedom, ready to do anything, go anywhere, pausing long enough for In the heyday of rockabilly, one imagines more than a few young men apologies and recriminations, but then hustling on towards the new'. -

Full Text in Diva

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in . Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Krzyzanowska, N. (2017) (Counter)Monuments and (Anti)Memory in the City. An Aesthetic and Socio- Theoretical Approach. The Polish Journal of Aesthetics, 47(4): 109-128 https://doi.org/10.19205/47.17.6 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:oru:diva-63813 47 (4/2017), pp. 109–128 The Polish Journal DOI: 10.19205/47.17.6 of Aesthetics Natalia Krzyżanowska* (Counter)Monuments and (Anti)Memory in the City. An Aesthetic and Socio-Theoretical Approach Abstract This article reflects upon the possibility of the visualisation of different forms of collective memory in the city. It focuses on the evolution of the ways of commemorating in public spaces. It juxtaposes traditional monuments erected in commemoration of an event or an “important” person for a community with (counter)monuments as a modern, critical reaction geared towards what is either ignored in historical narratives or what remains on the fringe of collective memory. While following a theoretical exploration of the concepts of memory and their fruition in monuments as well as (counter)monuments, the eventual multimodal analysis central to the paper looks in-depth at Ruth Beckermann’s work The Missing Image (Vienna, 2015). The latter is treated as an example of the possible and manifold interpretations of the function and multiplicity of meanings that (counter)- monuments bring to contemporary urban spaces. -

Sufism Veil and Quintessence by Frithjof Schuon

Islam/Sufi sm Schuon is revised and expanded edition of Frithjof Schuon’s Su sm: Veil and Quintessence contains: Sufi sm a new translation of this classic work; previously unpublished correspondence by Veil and Quintessence Frithjof Schuon; an editor’s preface by James S. Cutsinger; A New Translation with Selected Letters a new foreword by Seyyed Hossein Nasr; extensive editor’s notes by James S. Cutsinger; a glossary of foreign terms and phrases; an index; and biographical notes. Sufi sm: Veil sm: Veil Sufi “ is small book is a fascinating interpretation of Islam by the leading philosopher of Islamic theosophical mysticism. e book is an excellent introduction into the higher aspects of Su sm.” —Annemarie Schimmel, Harvard University “In this book one can discover with greater clarity than any other available work the distinction between that quintessential Su sm which comprises the very heart of the message of Su sm and the more exteriorized forms of Islam. No other work succeeds so well in removing the most formidable and notable impediments in the understanding of the authentic Su tradition for the Western reader.” and —Seyyed Hossein Nasr, the George Washington University Quintessence “Schuon’s thought does not demand that we agree or disagree, but that we understand or do not understand. Such writing is of rare and lasting value.” —Times Literary Supplement “If I were asked who is the greatest writer of our time, I would say Frithjof Schuon without hesitation.” —Martin Lings, author of Muhammad: His Life Based on the Earliest Sources Frithjof Schuon, philosopher and metaphysician, is the best known proponent of the Perennial Philosophy. -

Birds & Culture on the Maharajas' Express

INDIA: BIRDS & CULTURE ON THE MAHARAJAS’ EXPRESS FEBRUARY 10–26, 2021 KANHA NATIONAL PARK PRE-TRIP FEBRUARY 5–11, 2021 KAZIRANGA NATIONAL PARK EXTENSION FEBRUARY 26–MARCH 3, 2021 ©2020 Taj Mahal © Shutterstock Birds & Culture on the Maharajas’ Express, Page 2 There is something indefinable about India which makes westerners who have been there yearn to return. Perhaps it is the vastness of the country and its timeless quality. Perhaps it is the strange mixture of a multiplicity of peoples and cultures which strikes a hidden chord in us, for whom this land seems so alien and yet so fascinating. Or perhaps it is the way that humans and nature are so closely linked, co-existing in a way that seems highly improbable. There are some places in a lifetime that simply must be visited, and India is one of them. Through the years we have developed an expertise on India train journeys. It all started in 2001 when VENT inaugurated its fabulous Palace on Wheels tour. Subsequent train trips in different parts of the country were equally successful. In 2019, VENT debuted a fabulous new India train tour aboard the beautiful Maharajas’ Express. Based on the great success of this trip we will operate this special departure again in 2021! Across a broad swath of west-central India, we will travel in comfort while visiting the great princely cities of Rajasthan state: Udaipur, Jodhpur, and Jaipur; a host of wonderful national parks and preserves; and cultural wonders. Traveling in such style, in a way rarely experienced by modern-day travelers, will take us back in time and into the heart of Rajput country.