Reading Close Reading: Twentieth-Century Criticism, Twenty-First-Century Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literary Criticism and Theory in the African Novel

LITERARY CRITICISM AND THEORY IN THE AFRICAN NOVEL: . CIDNUAACBEBE AND ALI MAZRUI by AyoMamudu 'It simply dawned on me two mommgs ago that a novelist must listen to his characters who after all are created to wear the shoe and point the writer where it pinches' - lkem in achebe's Antbllls of the Savannah The successful creative writer is also in an obvious and fundamental sense a critic; he possesses the critical awareness and carries out the self-criticism without which a work of art of respectable quality cannot be produced. Indeed, T.S. Eliot, as is well-known. was led to opine that "it is to be expected that the critic and the creative artist should frequently be the same person" .1 In contemporacy Africa, the view is widely held that the creative sensibility is other than and superior to the critical; and, in the tradition of the wide-spread and age-long "dispute" between writers and critics. that the critic is a junior partner (to the writer), even a parasite.2 Yet the evidence is abundant that some of Africa's leading writers have also produced considerable and compelling criticism: Achebe, Ngugi and Soyinka, to name a few. Their independent criticalworks aside, African writers have continued in their creative works to give information and shed light on critical and literary theory. The special attraction ofthis practice ofembedding, hinting at or discussing critical and literary ideas or views in creative writing is that the cut and thrust of contemporacy critical debates. the shifting sands of critical taste and fashion, and the interweaving of personal.opinion and public demands are gathered up and sifted through the imaginative process and the requirements ofthe particular literacy genre; its greatest danger is to be expected from a disregard for the imperatives of form. -

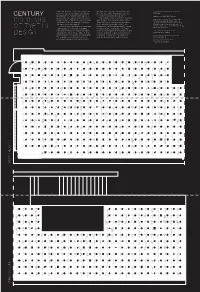

Century 100 Years of Type in Design

Bauhaus Linotype Charlotte News 702 Bookman Gilgamesh Revival 555 Latin Extra Bodoni Busorama Americana Heavy Zapfino Four Bold Italic Bold Book Italic Condensed Twelve Extra Bold Plain Plain News 701 News 706 Swiss 721 Newspaper Pi Bodoni Humana Revue Libra Century 751 Boberia Arriba Italic Bold Black No.2 Bold Italic Sans No. 2 Bold Semibold Geometric Charlotte Humanist Modern Century Golden Ribbon 131 Kallos Claude Sans Latin 725 Aurora 212 Sans Bold 531 Ultra No. 20 Expanded Cockerel Bold Italic Italic Black Italic Univers 45 Swiss 721 Tannarin Spirit Helvetica Futura Black Robotik Weidemann Tannarin Life Italic Bailey Sans Oblique Heavy Italic SC Bold Olbique Univers Black Swiss 721 Symbol Swiss 924 Charlotte DIN Next Pro Romana Tiffany Flemish Edwardian Balloon Extended Bold Monospaced Book Italic Condensed Script Script Light Plain Medium News 701 Swiss 721 Binary Symbol Charlotte Sans Green Plain Romic Isbell Figural Lapidary 333 Bank Gothic Bold Medium Proportional Book Plain Light Plain Book Bauhaus Freeform 721 Charlotte Sans Tropica Script Cheltenham Humana Sans Script 12 Pitch Century 731 Fenice Empire Baskerville Bold Bold Medium Plain Bold Bold Italic Bold No.2 Bauhaus Charlotte Sans Swiss 721 Typados Claude Sans Humanist 531 Seagull Courier 10 Lucia Humana Sans Bauer Bodoni Demi Bold Black Bold Italic Pitch Light Lydian Claude Sans Italian Universal Figural Bold Hadriano Shotgun Crillee Italic Pioneer Fry’s Bell Centennial Garamond Math 1 Baskerville Bauhaus Demian Zapf Modern 735 Humanist 970 Impuls Skylark Davida Mister -

How Fun Are Your Meetings? Investigating the Relationship Between Humor Patterns in Team Interactions and Team Performance

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Psychology Faculty Publications Department of Psychology 11-2014 How fun are your meetings? Investigating the relationship between humor patterns in team interactions and team performance Nale Lehmann-Willenbrock Vrije University Amsterdam Joseph A. Allen University of Nebraska at Omaha, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/psychfacpub Part of the Industrial and Organizational Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Lehmann-Willenbrock, Nale and Allen, Joseph A., "How fun are your meetings? Investigating the relationship between humor patterns in team interactions and team performance" (2014). Psychology Faculty Publications. 118. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/psychfacpub/118 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Psychology at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Psychology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. In press at Journal of Applied Psychology How fun are your meetings? Investigating the relationship between humor patterns in team interactions and team performance Nale Lehmann-Willenbrock1 & Joseph A. Allen2 1 VU University Amsterdam 2 University of Nebraska at Omaha Acknowledgements The initial data collection for this study was partially supported by a grant from the German Research Foundation, which is gratefully acknowledged. We appreciate the support by Simone Kauffeld and the helpful feedback by Steve Kozlowski. Abstract Research on humor in organizations has rarely considered the social context in which humor occurs. One such social setting that most of us experience on a daily basis concerns the team context. Building on recent theorizing about the humor—performance association in teams, this study seeks to increase our understanding of the function and effects of humor in team interaction settings. -

Design One Project Three Introduced October 21. Due November 11

Design One Project Three Introduced October 21. Due November 11. Typeface Broadside/Poster Broadsides have been an aspect of typography and printing since the earliest types. Printers and Typographers would print a catalogue of their available fonts on one large sheet of paper. The introduction of a new typeface would also warrant the issue of a broadside. Printers and Typographers continue to publish broadsides, posters and periodicals to advertise available faces. The Adobe website that you use for research is a good example of this purpose. Advertising often interprets the type creatively and uses the typeface in various contexts to demonstrate its usefulness. Type designs reflect their time period and the interests and experiences of the type designer. Type may be planned to have a specific “look” and “feel” by the designer or subjective meaning may be attributed to the typeface because of the manner in which it reflects its time, the way it is used, or the evolving fashion of design. For this third project, you will create two posters about a specific typeface. One poster will deal with the typeface alone, cataloguing the face and providing information about the type designer. The second poster will present a visual analogy of the typeface, that combines both type and image, to broaden the viewer’s knowledge of the type. Process 1. Research the history and visual characteristics of a chosen typeface. Choose a typeface from the list provided. -Write a minimum150 word description of the typeface that focuses on two themes: A. The historical background of the typeface and a very brief biography of the typeface designer. -

Cloud Fonts in Microsoft Office

APRIL 2019 Guide to Cloud Fonts in Microsoft® Office 365® Cloud fonts are available to Office 365 subscribers on all platforms and devices. Documents that use cloud fonts will render correctly in Office 2019. Embed cloud fonts for use with older versions of Office. Reference article from Microsoft: Cloud fonts in Office DESIGN TO PRESENT Terberg Design, LLC Index MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS A B C D E Legend: Good choice for theme body fonts F G H I J Okay choice for theme body fonts Includes serif typefaces, K L M N O non-lining figures, and those missing italic and/or bold styles P R S T U Present with most older versions of Office, embedding not required V W Symbol fonts Language-specific fonts MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS Abadi NEW ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Abadi Extra Light ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Note: No italic or bold styles provided. Agency FB MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Agency FB Bold ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Note: No italic style provided Algerian MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 01234567890 Note: Uppercase only. No other styles provided. Arial MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Italic ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Bold ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Bold Italic ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ -

Spring-And-Summer-Fun-Pack.Pdf

Spring & Summer FUN PACK BUILD OUR KIDS' SUCCESS Find many activities for kids in Kindergarten through Grade 9 to get moving and stay busy during the warmer months. Spring & Summer FUN PACK WHO IS THIS BOOKLET FOR? 1EVERYONE – kids, parents, camps, childcare providers, and anyone that is involved with kids this summer. BOKS has compiled a Spring & Summer Fun Pack that is meant to engage kids and allow them to “Create Their Own Adventure of Fun” for the warmer weather months. This package is full of easy to follow activities for kids to do independently, as a family, or for camp counselors/childcare providers to engage kids on a daily basis. We have included a selection of: BOKS Bursts (5–10 minute activity breaks) BOKS lesson plans - 30 minutes of fun interactive lessons including warm ups, skill work, games and nutrition bits with video links Crafts Games Recipes HOW DOES THIS WORK? Choose two or three activities daily from the selection outlined on page 4: 1. Get physically active with Bursts and/or BOKS fitness classes. 2. Be creative with cooking and crafts. 3. Have fun outdoors (or indoors), try our games! How do your kids benefit? • Give kids time to play and have fun. • Get kids moving toward their 60 minutes of recommended daily activity. • Build strong bones and muscles with simple fitness skills. • Reduce symptoms of anxiety. • Encourage a love of physical activity through engaging games. • We encourage your kids to have fun creating their own BOKS adventure. WHO WE ARE… BOKS (Build Our Kids' Success) is a FREE physical activity program designed to get kids active and establish a lifelong commitment to health and fitness. -

Ohio Graduation Tests

---~ Department of Education Student Name OHIO GRADUATION TESTS Reading Spring 2008 This test was originally administered to students in March 2008. This publicly released material is appropriate for use by Ohio teachers in instructional settings. This test is aligned with Ohio’s Academic Content Standards. © 2008 by Ohio Department of Education The Ohio Department of Education does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, or disability in employment or the provision of services. The Ohio Department of Education acknowledges that copyrighted material may contain information that is not currently accurate and assumes no responsibility for material reproduced in this document that reflects such inaccuracies. Form A Reading READING TEST Directions: Each passage in this test is followed by several questions. After reading the passage, choose the correct answer for each multiple-choice question, and then mark the corresponding circle in the Answer Document. If you change an answer, be sure to erase the first mark completely. For the written-response questions, answer completely in the Answer Document in the space provided. You may not need to use the entire space provided. You may refer to the passages as often as necessary. Make sure the number of the question in this test booklet corresponds to the number on the Answer Document. Be sure all your answers are complete and appear in the Answer Document. The Sweat-Soaked Life of a Glamorous Rockette by Susan Dominus 1 One after the other, like beautiful, glittering drones, the Rockettes spilled off an elevator onto the stage level at Radio City Music Hall. -

“English”: the Influence of British and American Thought on His Philosophy Written by Thomas H

Book Review Nietzsche and the “English”: The Influence of British and American Thought on His Philosophy written by Thomas H. Brobjer (New York: Humanities Books, 2008) reviewed by Martine Prange (University of Amsterdam & Maastricht University) ietzsche did not know English well and he Nnever visited the British Isles. He accused ‘the small-spiritedness of England’ to be ‘now the great danger on Earth’ and he dismissed the English for be- ing ‘no philosophical race’ (BGE 252). Nevertheless, in his new book Nietzsche and the “English” (which term refers to what we now call ‘Anglo-American’ philosophy and literature), Thomas Brobjer, associ- ate professor in the History of Science and Ideas at the University of Uppsala, sets out to show that such statements conceal the fact that ‘many of Nietzsche’s favourite authors were British and American and dur- ing two extended periods of his life Nietzsche was enthusiastic about and highly interested in British and American thinking and literature, and read intensively works by and about British authors’ (12). He further claims that those readings had a much deeper impact on Nietzsche’s philosophy than recognized so far, in both negative and positive ways. On a more general level, he wants to reveal how Nietzsche worked and thought by focusing on his response to his readings. Thus, Brobjer researches what Nietzsche read, when he read it, how seriously he read it, and in which manner his readings influenced his thought. Brobjer’s claims spur curiosity. Who exactly were those British and American -

Gilles Deleuze's American Rhizome by Michelle Renae Koerner the Graduate Program in Literature

The Uses of Literature: Gilles Deleuze’s American Rhizome by Michelle Renae Koerner The Graduate Program in Literature Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Kenneth Surin, Co-Chair ___________________________ Priscilla Wald, Co-Chair ___________________________ Wahneema Lubiano ___________________________ Frederick Moten ___________________________ Michael Hardt Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Program in Literature in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 i v iv ABSTRACT The Uses of Literature: Gilles Deleuze’s American Rhizome by Michelle Renae Koerner The Graduate Program in Literature Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Kenneth Surin, Co-Chair ___________________________ Priscilla Wald, Co-Chair ___________________________ Wahneema Lubiano ___________________________ Frederick Moten ___________________________ Michael Hardt An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Program in Literature in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 Copyright by Michelle Renae Koerner 2010 Abstract “The Uses of Literature: Gilles Deleuze’s American Rhizome” puts four writers – Walt Whitman, Herman Melville, George Jackson and William S. Burroughs – in conjunction with four concepts – becoming-democratic, belief in the world, the line of flight, and finally, control societies. The aim of this -

DISGUST: Features and SAWCHUK and Clinical Implications

Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 24, No. 7, 2005, pp. 932-962 OLATUNJIDISGUST: Features AND SAWCHUK and Clinical Implications DISGUST: CHARACTERISTIC FEATURES, SOCIAL MANIFESTATIONS, AND CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS BUNMI O. OLATUNJI University of Massachusetts CRAIG N. SAWCHUK University of Washington School of Medicine Emotions have been a long–standing cornerstone of research in social and clinical psychology. Although the systematic examination of emotional processes has yielded a rather comprehensive theoretical and scientific literature, dramatically less empirical attention has been devoted to disgust. In the present article, the na- ture, experience, and other associated features of disgust are outlined. We also re- view the domains of disgust and highlight how these domains have expanded over time. The function of disgust in various social constructions, such as cigarette smoking, vegetarianism, and homophobia, is highlighted. Disgust is also becoming increasingly recognized as an influential emotion in the onset, maintenance, and treatment of various phobic states, Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder, and eating disorders. In comparison to the other emotions, disgust offers great promise for fu- ture social and clinical research efforts, and prospective studies designed to improve our understanding of disgust are outlined. The nature, structure, and function of emotions have a rich tradition in the social and clinical psychology literature (Cacioppo & Gardner, 1999). Although emotion theorists have contested over the number of discrete emotional states and their operational definitions (Plutchik, 2001), most agree that emotions are highly influential in organizing thought processes and behavioral tendencies (Izard, 1993; John- Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by NIMH NRSA grant 1F31MH067519–1A1 awarded to Bunmi O. -

Mathematics K Through 6

Building fun and creativity into standards-based learning Mathematics K through 6 Ron De Long, M.Ed. Janet B. McCracken, M.Ed. Elizabeth Willett, M.Ed. © 2007 Crayola, LLC Easton, PA 18044-0431 Acknowledgements Table of Contents This guide and the entire Crayola® Dream-Makers® series would not be possible without the expertise and tireless efforts Crayola Dream-Makers: Catalyst for Creativity! ....... 4 of Ron De Long, Jan McCracken, and Elizabeth Willett. Your passion for children, the arts, and creativity are inspiring. Thank you. Special thanks also to Alison Panik for her content-area expertise, writing, research, and curriculum develop- Lessons ment of this guide. Garden of Colorful Counting ....................................... 6 Set representation Crayola also gratefully acknowledges the teachers and students who tested the lessons in this guide: In the Face of Symmetry .............................................. 10 Analysis of symmetry Barbi Bailey-Smith, Little River Elementary School, Durham, NC Gee’s-o-metric Wisdom ................................................ 14 Geometric modeling Rob Bartoch, Sandy Plains Elementary School, Baltimore, MD Patterns of Love Beads ................................................. 18 Algebraic patterns Susan Bivona, Mount Prospect Elementary School, Basking Ridge, NJ A Bountiful Table—Fair-Share Fractions ...................... 22 Fractions Jennifer Braun, Oak Street Elementary School, Basking Ridge, NJ Barbara Calvo, Ocean Township Elementary School, Oakhurst, NJ Whimsical Charting and -

Children's Classics Through the Lenses of Literary Theory

Children’s Classics Through The Lenses of Literary Theory Adam Georgandis Bellaire High School INTRODUCTION Literary theory is largely absent from high school English courses. While virtually all high school students read and respond to literature, few are given opportunities to analyze the works they read using established, critical methods. This curriculum unit will introduce high school students to four critical approaches, and it will ask students to apply each approach to selected works of children’s literature. Four methods of literary criticism - feminism, Marxism, post-colonial criticism, and reader-centered criticism – are especially useful in understanding the wide variety of texts students study in high school and college English courses. Feminist criticism suggests that readers can fully comprehend works of literature only when they pay particular attention to the dynamics of gender. Many high school readers are naturally drawn to the issue of gender. In several canonical works – The Scarlet Letter and The Awakening are good examples – understanding the roles of key female characters is an important and provocative task. Our use of feminist criticism will produce interesting discussions of traditional gender roles and societal expectations in literature and in the world of daily experience. Marxist criticism suggests that readers must closely examine the dynamics of class as they strive to understand the works they read. Many students focus naturally on the issue of class when they read works which explicitly call attention to it – the novels of John Steinbeck and Richard Wright, for example. Extending this focus to works of literature which do not call particular attention to class struggle will be a challenging and potentially rewarding endeavor.