Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21St Century Chicago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

Mike Mangini

/.%/&4(2%% 02):%3&2/- -".#0'(0%4$)3*4"%-&34&55*/(4*()54 7). 9!-!(!$25-3 VALUED ATOVER -ARCH 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE 0/5)& '0$64)*)"5 "$)*&7&5)&$-"44*$ 48*/(406/% "35#-",&: 5)&.&/503 50%%46$)&3."/ 45:-&"/%"/"-:4*4 $2%!-4(%!4%23 Ê / Ê" Ê," Ê/"Ê"6 , /Ê-1 -- (3&(03:)65$)*/40/ 8)&3&+";;41"45"/%'6563&.&&5 #6*-%:06308/ .6-5*1&%"-4&561 -ODERN$RUMMERCOM 3&7*&8&% 5"."4*-7&345"33&.0108&34530,&130-6%8*("5-"4130)"3%8"3&3*.4)05-0$."55/0-"/$:.#"-4 Volume 36, Number 3 • Cover photo by Paul La Raia CONTENTS Paul La Raia Courtesy of Mapex 40 SETTING SIGHTS: CHRIS ADLER Lamb of God’s tireless sticksman embraces his natural lefty tendencies. by Ken Micallef Timothy Saccenti 54 MIKE MANGINI By creating layers of complex rhythms that complement Dream Theater’s epic arrangements, “the new guy” is ushering in a bold and exciting era for the band, its fans, and progressive rock music itself. by Mike Haid 44 GREGORY HUTCHINSON Hutch might just be the jazz drummer’s jazz drummer— historically astute and futuristically minded, with the kind 12 UPDATE of technique, soul, and sophistication that today’s most important artists treasure. • Manraze’s PAUL COOK by Ken Micallef • Jazz Vet JOEL TAYLOR • NRBQ’s CONRAD CHOUCROUN • Rebel Rocker HANK WILLIAMS III Chuck Parker 32 SHOP TALK Create a Stable Multi-Pedal Setup 36 PORTRAITS NYC Pocket Master TONY MASON 98 WHAT DO YOU KNOW ABOUT...? Faust’s WERNER “ZAPPI” DIERMAIER One of Three Incredible 70 INFLUENCES: ART BLAKEY Prizes From Yamaha Drums Enter to Win We all know those iconic black-and-white images: Blakey at the Valued $ kit, sweat beads on his forehead, a flash in the eyes, and that at Over 5,700 pg 85 mouth agape—sometimes with the tongue flat out—in pure elation. -

Joseph Jarman's Black Case Volume I & II: Return

Joseph Jarman’s Black Case Volume I & II: Return From Exile February 13, 2020 By Cam Scott When composer, priest, poet, and instrumentalist Joseph Jarman passed away in January 2019, a bell sounded in the hearts of thousands of listeners. As an early member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), as well as its flagship group, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Jarman was a key figure in the articulation of Great Black Music as a multi- generational ethic rather than a standard repertoire. As an ordained Buddhist priest, Jarman’s solicitude transcended philosophical affinity and deepened throughout his life as his music evolved. His musical, poetic, and religious paths appear to have been mutually informative, in spite of a hiatus from public performance in the nineties—and to encounter Jarman’s own words is to understand as much. The full breadth of this complexity is celebrated in the long-awaited reissue of Black Case Volume I & II: Return from Exile, a blend of smut and sutra, poetry and polemic, that feels like a reaffirmation of Jarman’s ambitious vision in the present day. Black Case wears its context proudly. A near-facsimile of the original 1977 publication by the Art Ensemble of Chicago (which itself was built upon a coil-bound printing from 1974), the volume serves as a time capsule of a key period in the development of an emancipatory musical and cultural program, and an intimate portrait of the artist-as-revolutionary. Black Case, then, feels most contemporary where it is most of its time, as a document of Black militancy and programmatic self-determination in which—to paraphrase Larry Neal’s 1968 summary of the Black Arts Movement—ethics and aesthetics, individual and community, are tightly unified. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

Nonprofit Security Grant Program Threat Incident Report

Nonprofit Security Grant Program Threat Incident Report: January 2019 to Present November 15, 2020 (Updated 02/22/2021) Prepared By: Rob Goldberg, Senior Director, Legislative Affairs [email protected] The following is a compilation of recent threat incidents, at home or abroad, targeting Jews and Jewish institutions (and other faith-based organization) that have been reported in the public record. When completing the Threat section of the IJ (Part III. Risk): ▪ First Choice: Describe specific terror (or violent homegrown extremist) incidents, threats, hate crimes, and/or related vandalism, trespass, intimidation, or destruction of property that have targeted its property, membership, or personnel. This may also include a specific event or circumstance that impacted an affiliate or member of the organization’s system or network. ▪ Second Choice: Report on known incidents/threats that have occurred in the community and/or State where the organization is located. ▪ Third Choice: Reference the public record regarding incidents/threats against similar or like institutions at home or abroad. Since there is limited working space in the IJ, the sub-applicant should be selective in choosing appropriate examples to incorporate into the response: events that are most recent, geographically proximate, and closely related to their type or circumstance of their organization or are of such magnitude or breadth that they create a significant existential threat to the Jewish community at large. I. Overview of Recent Federal Risk Assessments of National Significance Summary The following assessments underscore the persistent threat of lethal violence and hate crimes against the Jewish community and other faith- and community-based institutions in the United States. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1990

National Endowment For The Arts Annual Report National Endowment For The Arts 1990 Annual Report National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1990. Respectfully, Jc Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. April 1991 CONTENTS Chairman’s Statement ............................................................5 The Agency and its Functions .............................................29 . The National Council on the Arts ........................................30 Programs Dance ........................................................................................ 32 Design Arts .............................................................................. 53 Expansion Arts .....................................................................66 ... Folk Arts .................................................................................. 92 Inter-Arts ..................................................................................103. Literature ..............................................................................121 .... Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ..................................137 .. Museum ................................................................................155 .... Music ....................................................................................186 .... 236 ~O~eera-Musicalater ................................................................................ -

Colby Alumnus Vol. 65, No. 2: Winter 1976

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Colby Alumnus Colby College Archives 1976 Colby Alumnus Vol. 65, No. 2: Winter 1976 Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/alumnus Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Colby College, "Colby Alumnus Vol. 65, No. 2: Winter 1976" (1976). Colby Alumnus. 90. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/alumnus/90 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Colby College Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Alumnus by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. The Colby Alumnus Volume 65, Number 2 Winter 1976 Published quarterly fall, winter, spring, summer by Colby College Editorial board Mark Shankland Earl H. Smith Design and production Donald E. Sanborn, Jr. Martha Freese Photography Mark Shankland Letters and inquiries should be sent to the editor, change of address notification to the alumni office Entered as second-class mail at Waterville, Maine Postmaster send form 3579 to The Colby Alumnus Colby College Waterville, Maine 04901 appraisal of the future of professions, or just in our President's Page personal arrangements for the security and well-being of ourselves and our families, we must take these changes into account and must assume that there will President Robert E. L. Strider gave the keynote address be continuing acceleration of change for all the span of to a conference of the Northeastern Industrial Devel years that most of us can foresee. opers Association recently in Portland. The conference I am surely not suggesting that this state of affairs is theme was "Survival Demands Sensitivity to Change." bad. -

May-June 293-WEB

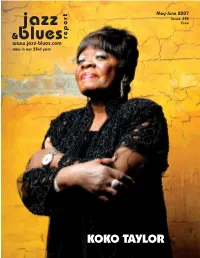

May-June 2007 Issue 293 jazz Free &blues report www.jazz-blues.com now in our 33rd year KOKO TAYLOR KOKO TAYLOR Old School Published by Martin Wahl A New CD... Communications On Tour... Editor & Founder Bill Wahl & Appearing at the Chicago Blues Festival Layout & Design Bill Wahl The last time I saw Koko Taylor Operations Jim Martin she was a member of the audience at Pilar Martin Buddy Guy’s Legends in Chicago. It’s Contributors been about 15 years now, and while I Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, no longer remember who was on Kelly Ferjutz, Dewey Forward, stage that night – I will never forget Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, Koko sitting at a table surrounded by Peanuts, Wanda Simpson, Mark fans standing about hoping to get an Smith, Dave Sunde, Duane Verh, autograph...or at least say hello. The Emily Wahl and Ron Weinstock. Queen of the Blues was in the house that night...and there was absolutely Check out our costantly updated no question as to who it was, or where website. Now you can search for CD Reviews by artists, titles, record she was sitting. Having seen her elec- labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 trifying live performances several years of reviews are up and we’ll be times, combined with her many fine going all the way back to 1974. Alligator releases, it was easy to un- derstand why she was engulfed by so Koko at the 2006 Pocono Blues Festival. Address all Correspondence to.... many devotees. Still trying, but I still Jazz & Blues Report Photo by Ron Weinstock. -

Feature Film Project Summary Logline Synopsis

HERE Feature Film Project Summary A Braden King Film Written by Braden King and Dani Valent Producers: Lars Knudsen, Jay Van Hoy Co-Producer: Jeff Kalousdian Executive Producers: Zoe Kevork, Julia King A Truckstop Media / Parts and Labor Production 302A W. 12th St., #223 New York, New York 10014 (212) 989-7105 / [email protected] www.herefilm.info Logline HERE is a dramatic, landscape-obsessed road movie that chronicles a brief but intense romantic relationship between an American satellite-mapping engineer and an expatriate Armenian art photographer who impulsively decide to travel together into uncharted territory. Synopsis Will Shepard is an American satellite-mapping engineer contracted to create a new, more accurate survey of the country of Armenia. Within the industry, his solitary work - land-surveying satellite images to check for accuracy and resolve anomalies - is called “ground-truthing”. He’s been doing it on his own, for years, all over the world. But on this trip, his measurements are not adding up. Will meets Gadarine Najarian at a rural hotel. Tough and intriguing, she’s an expatriate Armenian art photographer on her first trip back in ages, passionately trying to figure out what kind of relationship - if any - she still has with her home country and culture. Fiercely independent, Gadarine is struggling to resolve the life she’s led abroad with the Armenian roots that run so deeply through her. There is an instant, unconscious bond between these two lone travelers; they impulsively decide to continue together. HERE tells the story of their unique journey and the dramatic personal transformations it leads each of them through. -

Debates in the Digital Humanities This Page Intentionally Left Blank DEBATES in the DIGITAL HUMANITIES

debates in the digital humanities This page intentionally left blank DEBATES IN THE DIGITAL HUMANITIES Matthew K. Gold editor University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis London Chapter 1 was previously published as “What Is Digital Humanities and What’s It Doing in English Departments?” ADE Bulletin, no. 150 (2010): 55– 61. Chap- ter 2 was previously published as “The Humanities, Done Digitally,” The Chron- icle of Higher Education, May 8, 2011. Chapter 17 was previously published as “You Work at Brown. What Do You Teach?” in #alt- academy, Bethany Nowviskie, ed. (New York: MediaCommons, 2011). Chapter 28 was previously published as “Humanities 2.0: Promises, Perils, Predictions,” PMLA 123, no. 3 (May 2008): 707– 17. Copyright 2012 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by the University of Minnesota Press 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290 Minneapolis, MN 55401- 2520 http://www.upress.umn.edu library of congress cataloging-in-publication data Debates in the digital humanities / [edited by] Matthew K. Gold. ISBN 978-0-8166-7794-8 (hardback)—ISBN 978-0-8166-7795-5 (pb) 1. Humanities—Study and teaching (Higher)—Data processing. 2. Humanities —Technological innovations. 3. Digital media. I. Gold, Matthew K.. AZ182.D44 2012 001.3071—dc23 2011044236 Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper The University of Minnesota is an equal- opportunity educator and employer. -

JREV3.8FULL.Pdf

JAZZ WRITING? I am one of Mr. Turley's "few people" who follow The New Yorker and are jazz lovers, and I find in Whitney Bal- liett's writing some of the sharpest and best jazz criticism in the field. He has not been duped with "funk" in its pseudo-gospel hard-boppish world, or- with the banal playing and writing of some of the "cool school" Californians. He does believe, and rightly so, that a fine jazz performance erases the bound• aries of jazz "movements" or fads. He seems to be able to spot insincerity in any phalanx of jazz musicians. And he has yet to be blinded by the name of a "great"; his recent column on Bil- lie Holiday is the most clear-headed analysis I have seen, free of the fan- magazine hero-worship which seems to have been the order of the day in the trade. It is true that a great singer has passed away, but it does the late Miss Holiday's reputation no good not to ad• LETTERS mit that some of her later efforts were (dare I say it?) not up to her earlier work in quality. But I digress. In Mr. Balliett's case, his ability as a critic is added to his admitted "skill with words" (Turley). He is making a sincere effort to write rather than play jazz; to improvise with words,, rather than notes. A jazz fan, in order to "dig" a given solo, unwittingly knows a little about the equipment: the tune being improvised to, the chord struc• ture, the mechanics of the instrument, etc. -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black ..................................