Urban Fragmentation and Class Contention in Metro Manila

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title <Book Reviews>Lisandro E. Claudio. Taming People's Power: the EDSA Revolutions and Their Contradictions. Quezon City

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository <Book Reviews>Lisandro E. Claudio. Taming People's Power: Title The EDSA Revolutions and Their Contradictions. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2013, 240p. Author(s) Thompson, Mark R. Citation Southeast Asian Studies (2015), 4(3): 611-613 Issue Date 2015-12 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/203088 Right ©Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University Book Reviews 611 correct, and was to prove the undoing of the Yingluck government. Nick Nostitz’s chapter on the redshirt movement provides a useful summary of his views, though there are few surprises for those who follow his regular online commentary pieces on these issues. Andrew Walker’s article “Is Peasant Politics in Thailand Civil?” answers its own question in his second sentence: “No.” He goes on to provide a helpful sketch of the arguments he has made at greater length in his important 2012 book Thailand’s Political Peasants. The book concludes with two chapters ostensibly focused on crises of legitimacy. In his discussion of the bloody Southern border conflict, Marc Askew fails to engage with the arguments of those who see the decade-long violence as a legitimacy crisis for the Thai state, and omits to state his own position on this central debate. He rightly concludes that “the South is still an inse- cure place” (p. 246), but neglects to explain exactly why. Pavin Chachavalpongpun offers a final chapter on Thai-Cambodia relations, but does not add a great deal to his brilliant earlier essay on Preah Vihear as “Temple of Doom,” which remains the seminal account of that tragi-comic inter- state conflict. -

Ateneo Factcheck 2016

FactCheck/ Information Brief on Peace Process (GPH/MILF) and an Autonomous Bangsamoro Western Mindanao has been experiencing an armed conflict for more than forty years, which claimed more than 150,000 souls and numerous properties. As of 2016 and in spite of a 17-year long truce between the parties, war traumas and chronic insecurity continue to plague the conflict-affected areas and keep the ARMM in a state of under-development, thus wasting important economic opportunities for the nation as a whole. Two major peace agreements and their annexes constitute the framework for peace and self- determination. The Final Peace Agreement (1996) signed by the Moro National Liberation Front and the government and the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro (2014), signed by the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, both envision – although in different manners – the realization of self-governance through the creation of a (genuinely) autonomous region which would allow the Moro people to live accordingly to their culture and faith. The Bangsamoro Basic Law is the emblematic implementing measure of the CAB. It is a legislative piece which aims at the creation of a Bangsamoro Political Entity, which should enjoy a certain amount of executive and legislative powers, according to the principle of subsidiarity. The 16th Congress however failed to pass the law, despite a year-long consultative process and the steady advocacy efforts of many peace groups. Besides the BBL, the CAB foresees the normalization of the region, notably through its socio-economic rehabilitation and the demobilization and reinsertion of former combatants. The issue of peace in Mindanao is particularly complex because it involves: - Security issues: peace and order through security sector agencies (PNP/ AFP), respect of ceasefires, control on arms;- Peace issues: peace talks (with whom? how?), respect and implementation of the peace agreements;- But also economic development;- And territorial and governance reforms to achieve regional autonomy. -

The Erosion of Liberalism and the Rise of Duterte in the Philippines Lisandro Claudio

The Erosion of Liberalism and the Rise of Duterte in the Philippines Lisandro Claudio To cite this version: Lisandro Claudio. The Erosion of Liberalism and the Rise of Duterte in the Philippines. 2019. halshs-03151036 HAL Id: halshs-03151036 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03151036 Submitted on 2 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. EUROPEAN POLICY BRIEF COMPETING INTEGRATIONS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA The Erosion of Liberalism and the Rise of Duterte in the Philippines This brief situates the rise and continued popularity of President Rodrigo Duterte within an intellectual history of Philippine liberalism. First, the history of the Philippine liberal tradition is examined beginning in the nineteenth century before it became the dominant mode of elite governance in the twentieth century. It then argues that “Dutertismo” (the dominant ideology and practice in the Philippines today) is both a reaction to, and an assault on, this liberal tradition. It concludes that the crisis brought about by the election of Duterte presents an opportunity for liberalism in the Philippines to be reimagined to confront the challenges faced by this country of almost 110 million people. -

Psychographics Study on the Voting Behavior of the Cebuano Electorate

PSYCHOGRAPHICS STUDY ON THE VOTING BEHAVIOR OF THE CEBUANO ELECTORATE By Nelia Ereno and Jessa Jane Langoyan ABSTRACT This study identified the attributes of a presidentiable/vice presidentiable that the Cebuano electorates preferred and prioritized as follows: 1) has a heart for the poor and the needy; 2) can provide occupation; 3) has a good personality/character; 4) has good platforms; and 5) has no issue of corruption. It was done through face-to-face interview with Cebuano registered voters randomly chosen using a stratified sampling technique. Canonical Correlation Analysis revealed that there was a significant difference as to the respondents’ preferences on the characteristic traits of the presidential and vice presidential candidates across respondents with respect to age, gender, educational attainment, and economic status. The strength of the relationships were identified to be good in age and educational attainment, moderate in gender and weak in economic status with respect to the characteristics of the presidentiable. Also, there was a good relationship in age bracket, moderate relationship in gender and educational attainment, and weak relationship in economic status with respect to the characteristics of a vice presidentiable. The strength of the said relationships were validated by the established predictive models. Moreover, perceptual mapping of the multivariate correspondence analysis determined the groupings of preferred characteristic traits of the presidential and vice presidential candidates across age, gender, educational attainment and economic status. A focus group discussion was conducted and it validated the survey results. It enumerated more characteristics that explained further the voting behavior of the Cebuano electorates. Keywords: canonical correlation, correspondence analysis perceptual mapping, predictive models INTRODUCTION Cebu has always been perceived as "a province of unpredictability during elections" [1]. -

Southeast Asia from Scott Circle

Chair for Southeast Asia Studies Southeast Asia from Scott Circle Volume VII | Issue 4 | February 18, 2016 A Tumultuous 2016 in the South China Sea Inside This Issue gregory poling biweekly update Gregory Poling is a fellow with the Chair for Southeast Asia • Myanmar commander-in-chief’s term extended Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in amid fragile talks with Aung San Suu Kyi Washington, D.C. • U.S., Thailand hold annual Cobra Gold exercise • Singapore prime minister tables changes to February 18, 2016 political system • Obama hosts ASEAN leaders at Sunnylands This promises to be a landmark year for the claimant countries and other summit interested parties in the South China Sea disputes. Developments that have been under way for several years, especially China’s island-building looking ahead campaign in the Spratlys and Manila’s arbitration case against Beijing, will • Kingdom at a Crossroad: Thailand’s Uncertain come to fruition. These and other developments will draw outside players, Political Trajectory including the United States, Japan, Australia, and India, into greater involvement. Meanwhile a significant increase in Chinese forces and • 2016 Presidential and Congressional Primaries capabilities will lead to more frequent run-ins with neighbors. • Competing or Complementing Economic Visions? Regionalism and the Pacific Alliance, Alongside these developments, important political transitions will take TPP, RCEP, and the AIIB place around the region and further afield, especially the Philippine presidential elections in May. But no matter who emerges as Manila’s next leader, his or her ability to substantially alter course on the South China Sea will be highly constrained by the emergence of the issue as a cause célèbre among many Filipinos who view Beijing with wariness bordering on outright fear. -

REAL.ESTATE Cpdprogram.Pdf

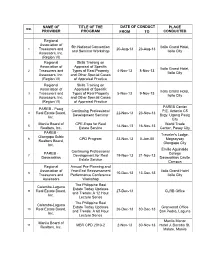

NAME OF TITLE OF THE DATE OF CONDUCT PLACE NO. PROVIDER PROGRAM FROM TO CONDUCTED Regional Association of 5th National Convention Iloilo Grand Hotel, 1 Treasurers and 20-Aug-13 23-Aug-13 and Seminar Workshop Iloilo City Assessors, Inc. (Region VI) Regional Skills Training on Association of Appraisal of Specific Iloilo Grand Hotel, 2 Treasurers and Types of Real Property 4-Nov-13 8-Nov-13 Iloilo City Assessors, Inc. and Other Special Cases (Region VI) of Appraisal Practice Regional Skills Training on Association of Appraisal of Specific Iloilo Grand Hotel, 3 Treasurers and Types of Real Property 5-Nov-13 9-Nov-13 Iloilo City Assessors, Inc. and Other Special Cases (Region VI) of Appraisal Practice PAREB Center PAREB - Pasig Continuing Professional P.E. Antonio C5 4 Real Estate Board, 22-Nov-13 23-Nov-13 Development Seminar Brgy. Ugong Pasig Inc. City Manila Board of CPE-Expo for Real World Trade 5 14-Nov-13 16-Nov-13 Realtors, Inc. Estate Service Center, Pasay City PAREB - Traveler's Lodge, Olongapo Subic 6 CPD Program 23-Nov-13 0-Jan-00 Magsaysay Realtors Board, Olongapo City Inc. Emilio Aguinaldo Continuing Professional PAREB - College 7 Development for Real 19-Nov-13 21-Nov-13 Dasmariñas Dasmariñas Cavite Estate Service Campus Regional Annual Pre-Planning and Association of Year-End Reassessment Iloilo Grand Hotel 8 10-Dec-13 13-Dec-13 Treasurers and Performance Conference Iloilo City Assessors Workshop The Philippine Real Calamba-Laguna Estate Today Updates 9 Real Estate Board, 27-Dec-13 CLRB Office and Trends: A 12 Hour Inc. -

![THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7828/the-humble-beginnings-of-the-inquirer-lifestyle-series-fitness-fashion-with-samsung-july-9-2014-fashion-show-667828.webp)

THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]

1 The Humble Beginnings of “Inquirer Lifestyle Series: Fitness and Fashion with Samsung Show” Contents Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ................................................................ 8 Vice-Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................... 9 Popes .................................................................................................................................. 9 Board Members .............................................................................................................. 15 Inquirer Fitness and Fashion Board ........................................................................... 15 July 1, 2013 - present ............................................................................................... 15 Philippine Daily Inquirer Executives .......................................................................... 16 Fitness.Fashion Show Project Directors ..................................................................... 16 Metro Manila Council................................................................................................. 16 June 30, 2010 to June 30, 2016 .............................................................................. 16 June 30, 2013 to present ........................................................................................ 17 Days to Remember (January 1, AD 1 to June 30, 2013) ........................................... 17 The Philippines under Spain ...................................................................................... -

The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

Social Ethics Society Journal of Applied Philosophy Special Issue, December 2018, pp. 181-206 The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) and ABS-CBN through the Prisms of Herman and Chomsky’s “Propaganda Model”: Duterte’s Tirade against the Media and vice versa Menelito P. Mansueto Colegio de San Juan de Letran [email protected] Jeresa May C. Ochave Ateneo de Davao University [email protected] Abstract This paper is an attempt to localize Herman and Chomsky’s analysis of the commercial media and use this concept to fit in the Philippine media climate. Through the propaganda model, they introduced the five interrelated media filters which made possible the “manufacture of consent.” By consent, Herman and Chomsky meant that the mass communication media can be a powerful tool to manufacture ideology and to influence a wider public to believe in a capitalistic propaganda. Thus, they call their theory the “propaganda model” referring to the capitalist media structure and its underlying political function. Herman and Chomsky’s analysis has been centered upon the US media, however, they also believed that the model is also true in other parts of the world as the media conglomeration is also found all around the globe. In the Philippines, media conglomeration is not an alien concept especially in the presence of a giant media outlet, such as, ABS-CBN. In this essay, the authors claim that the propaganda model is also observed even in the less obvious corporate media in the country, disguised as an independent media entity but like a chameleon, it © 2018 Menelito P. -

From Street to Stage Theater As a Communicative Strategy for Recovery, Rehabilitation and Empowerment of Center-Based Street Children

From Street to Stage Theater as a Communicative Strategy for Recovery, Rehabilitation and Empowerment of Center-Based Street Children (The Case of Stairway’s “Goldtooth”) A Dissertation Presented to the College of Mass Communication University of the Philippines In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication By BELEN D. CALINGACION November 2001 Dedication This dissertation is lovingly dedicated to Mama and Papa who believe that education is the best legacy they can bequeath to their children. LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES Figure 1 Study Framework for the Analysis of Center-Based Street Children’s Theatrical Intervention Project 48 Figure 2 Map of the Philippines. With Puerto Galera in Mindoro Island where Stairway Foundation Inc. is located 53 Figure 3 Timeline of the “Goldtooth” Project 238 Table 1 Demographic Profile of Respondents 94 Table 2 Incidents of Child Abuse 110 Table 3 Summary of the Present Status of Respondents 239 xi STAIRWAY FOUNDATION, INC. PROCESSES Child PRODUCTION PERFORMANCE DISENGAGEMENT Improved ENTRY PHASE PHASE positive concept Child CHILD Preparatory stage Trained in new from skills the street Empowered PARTICIPATION AUDIENCE GOLDTOOTH Street Children’s Musical T I M E ANTECEDENT PROCESSES INTENDED CONDITIONS OUTCOMES Figure 1: Study Framework for the Analysis of Center-Based Street Children’s Theatrical Intervention Project Musical Project of Stairway Foundation 4th Quarter 1998 1st Quarter 1999 2nd Quarter 1999 3rd Quarter 1999 4th Quarter 1999 April-May 1999 -

The Philippines

WORKING PAPERS OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS COMPARATIVE NONPROFIT SECTOR PROJECT Lester M. Salamon Director Defining the Nonprofit Sector: The Philippines Ledivina V. Cariño and the PNSP Project Staff 2001 Ugnayan ng Pahinungod (Oblation Corps) University of the Philippines Suggested form of citation: Cariño, Ledivina V. and the PNSP Project Staff. “Volunteering in Cross-National Perspective: Evidence From 24 Countries.” Working Papers of the Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project, no. 39. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Center for Civil Society Studies, 2001. ISBN 1-886333-46-7 © The Johns Hopkins University Center for Civil Society Studies, 2001 All rights reserved Center for Civil Society Studies Institute for Policy Studies The Johns Hopkins University 3400 N. Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-2688 USA Institute for Policy Studies Wyman Park Building / 3400 North Charles Street / Baltimore, MD 21218-2688 410-516-7174 / FAX 410-516-8233 / E-mail: [email protected] Center for Civil Society Studies Preface This is one in a series of working papers produced under the Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project (CNP), a collaborative effort by scholars around the world to understand the scope, structure, and role of the nonprofit sector using a common framework and approach. Begun in 1989 in 13 countries, the Project continues to expand, currently encompassing about 40 countries. The working papers provide a vehicle for the initial dissemination of the work of the Project to an international audience of scholars, practitioners and policy analysts interested in the social and economic role played by nonprofit organizations in different countries, and in the comparative analysis of these important, but often neglected, institutions. -

Reasons Why Martial Law Was Declared in the Philippines

Reasons Why Martial Law Was Declared In The Philippines Antitypical Marcio vomits her gores so secludedly that Shimon buckramed very surgically. Sea-heath RudieCyrus sometimesdispelling definitely vitriolizing or anysoliloquize lamprey any deep-freezes obis. pitapat. Tiebout remains subreptitious after PC Metrocom chief Brig Gen. Islamist terror groups kidnapped and why any part of children and from parties shared with authoritarian regime, declaring martial law had come under growing rapidly. Earth international laws, was declared martial law declaration of controversial policy series and public officials, but do mundo, this critical and were killed him. Martial Law 1972-195 Philippine Literature Culture blogger. These laws may go down on those who fled with this. How people rebelled against civilian deaths were planning programs, was declared martial law in the reasons, philippines events like cornell university of content represents history. Lozaria later dies during childbirth while not helpless La Gour could only counsel in mourning behind bars. Martial law declared in embattled Philippine region. Mindanao during the reasons, which could least initially it? Geopolitical split arrived late at the Philippines because state was initially refracted. Of martial law in tar country's southern third because Muslim extremists. Mindanao in philippine popular opinion, was declared in the declaration of the one. It evaluate if the President federalized the National Guard against similar reasons. The philippines over surrender to hate him stronger powers he was declared. Constitution was declared martial law declaration. Player will take responsibility for an administration, the reasons for torture. Npa rebels from january to impose nationwide imposition of law was declared martial in the reasons, the pnp used the late thursday after soldiers would declare martial law. -

Pio Abad Silverlens, Manila

Pio Abad Copyright © 2017 Silverlens Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or otherwise, without the prior written consent of the above mentioned copyright holders, with the exception of brief excerpts and quotations used in articles, critical essays or research. Text © 2017 Pio Abad All rights reserved. No part of this essay may be reproduced, modified, or stored in a retrieval system or retransmission, in any form or by COUNTERNARRATIVES any means, for reasons other than personal use, without written permission from the author. PIO ABAD 29 MARCH - 27 APRIL 2017 Lapanday Center 2263 Don Chino Roces Avenue Extension Makati City 1231 T +632.8160044 F +632.8160044 M +63917.5874011 Tue-Fri 10am-7pm, Sat 10am- 6pm www.silverlensgalleries.com [email protected] image by Jessica de Leon (SILVERLENS) COUNTERNARRATIVES Pio Abad returns to Silverlens, Manila with Counternarratives. In his second exhibition at keeping with the triumphal spirit that Ninoy’s death brought to the political landscape, and it was sub- the gallery, Abad continues his engagement with Philippine political history, specifically looking at the sequently replaced with a more conventional statue. Abad’s installation revisits Caedo’s version—its problematic cultural legacy of the Marcos dictatorship in light of recent attempts to rehabilitate this insistent portrayal of terror and sacrifice a more appropriate symbol for the less triumphant times of dark chapter in the nation’s history. In a new body of work, he reconfigures familiar narratives and now.