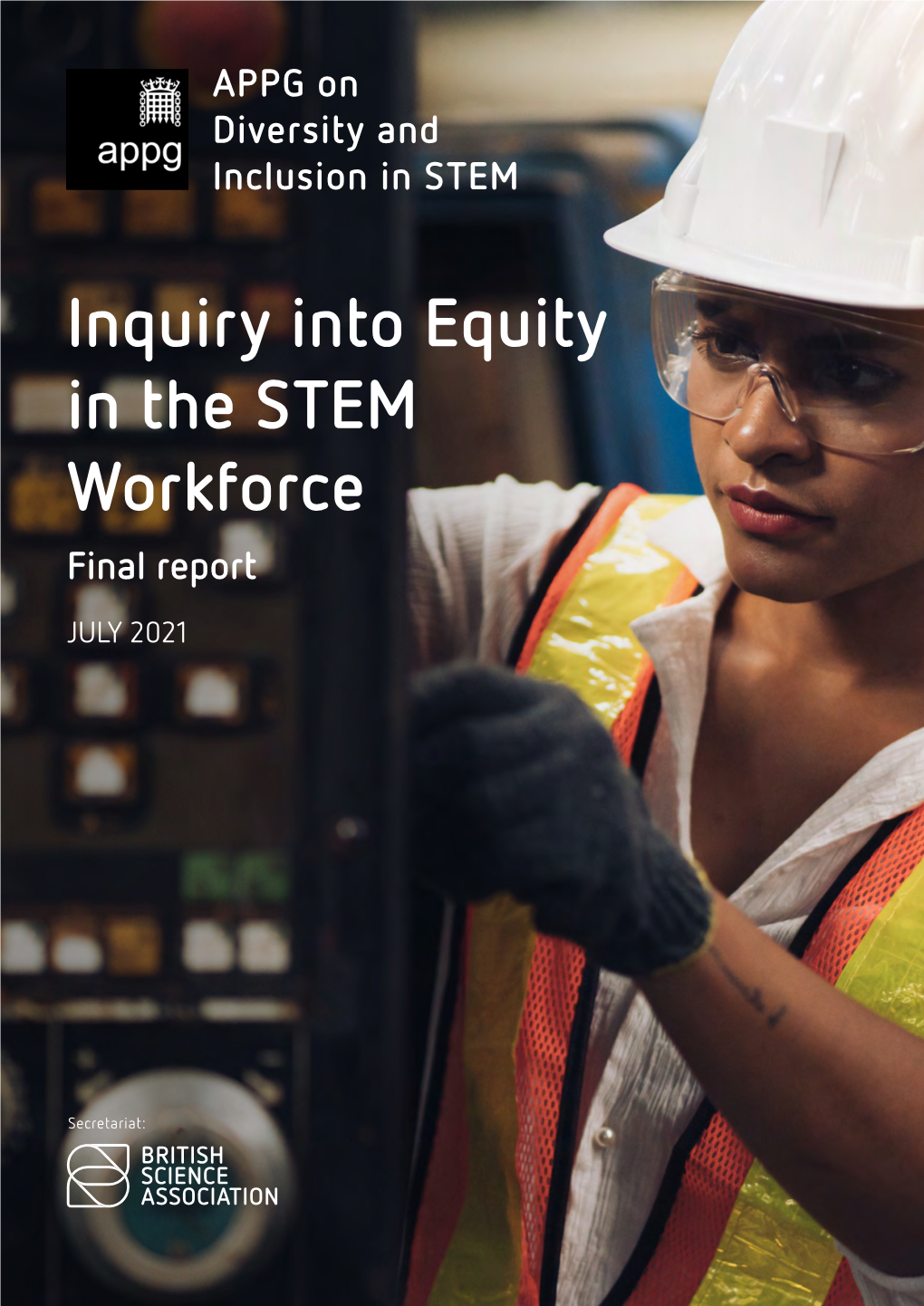

Inquiry Into Equity in the STEM Workforce Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chemistry for All Reducing Inequalities in Chemistry Aspirations and Attitudes

Chemistry for All Reducing inequalities in chemistry aspirations and attitudes Institute of Education 2 Chemistry for All Reducing inequalities in chemistry aspirations and attitudes Findings from the Chemistry for All research and evaluation programme November 2020 Authors Dr Tamjid Mujtaba Dr Richard Sheldrake Professor Michael J. Reiss UCL Institute of Education, University College London Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the students and staff from across the participating schools. The authors would also like to thank the Chemistry for All programme delivery teams and members of the programme steering group. The research was conducted independently by the UCL Institute of Education with funding from the Royal Society of Chemistry. For further information For further information on the Chemistry for All project, including requests for related publications or the next phase of the work, please contact Dr Tamjid Mujtaba ([email protected]). 3 1. Executive summary 5 9.3. Results for science as of Year 11 82 1.1. Background and context 6 9.3.1. Predicting students’ science aspirations 1.2. Chemistry for All programme 7 (A-Level, university, jobs) as of Year 11 82 1.3. Research and evaluation programme 7 9.3.2. Predicting students’ science aspirations for A-Level as of Year 11 85 CONTENTS 1.4. Research results and insights 8 1.4.1. Insights into students’ changing attitudes and aspirations 8 9.3.3. Predicting students’ science aspirations for careers as of Year 11 86 1.4.2. Insights into students’ attitudes and views 9 9.3.4. Predicting students’ science aspirations for university 1.4.3. -

The Case for a Gender Lens in STEM THROUGH BOTH Eyes: the Case for a Gender Lens in STEM ‘Think of a Gender Lens As Putting on Spectacles

THE CASE FOR A GENDER LENS IN STEM THROUGH BOTH eyes: The case for a gender lens in STEM ‘Think of a gender lens as putting on spectacles. Out of one lens of the spectacles, you see the participation, needs and realities of women. Out of the other lens, you see the participation, needs and realities of men. Your sight or vision is the combination of what each eye sees.’ 2 contents Contents EXECUTive summary 4 1.0 introduction 7 2.0 Challenges 8 3.0 Solutions 23 Sir Peter Luff MP: A Call to Action 49 References 50 Authorship & Credits 51 ‘The country urgently needs more young people with STEM qualifications, which means we have to get more girls and women involved. This should be at the heart of education and skills policy – it isn’t an optional extra left to a few passionate enthusiasts. We have to make it everyone’s business’ Helen Wollaston, Director WISE ‘Our research shows that it is harder for girls to balance, or reconcile, their interest in science with femininity. The solution won’t lie in trying to change girls. The causes are rooted in, and perpetuated by, wider societal attitudes and social structures. We also need to think about the whole structure of our education system in England, which essentially channels children into narrow ‘tracks’ from a young age’ Professor Louise Archer, Director of ASPIRES, ‘The lack of girls and women in STEM blights lead coordinatior of TISME our society and our economy. There is no single solution, which is why I am glad to see that Sciencegrrl have come forward with a wide range of recommendations covering education, careers and the broader cultural challenges’ Chi Onwurah, MP for Newcastle upon Tyne ‘We are working to maximise employer engagement to help put science and maths in a careers context. -

Engineering UK 2020 Report

Engineering UK 2020 Educational pathways into engineering Engineering UK 2020 Foreword Educational pathways into engineering Authors EngineeringUK would like to express sincere A central part of EngineeringUK’s work is to provide educators, policy-makers, industrialists and others with the most gratitude and special thanks to the following up-to-date analyses and insight. Since 2005, our EngineeringUK State of Engineering report has portrayed the breadth of Luke Armitage the sector, how it is changing and who is working within it, as well as quantifying students on educational pathways into Senior Research Analyst, EngineeringUK individuals, who contributed thought pieces or engineering and considering whether they will meet future workforce needs. Despite numerous changes of government Mollie Bourne acted as critical readers for this report: and educational policy, the 2008 recession and the advent of Brexit, the need for the UK to respond to the COVID-19 Research and Impact Manager, EngineeringUK Amanda Dickins pandemic has provided the most uncertain and challenging context to date for our research. Jess Di Simone Head of Impact and Development, STEM Learning Research Officer, EngineeringUK Teresa Frith Anna Jones Senior Skills Policy Manager, Association of Colleges Research Officer, EngineeringUK Ruth Gilligan Stephanie Neave Assistant Director for Equality Charters, AdvanceHE Our analyses for this report started before the pandemic • Ambitious plans to expand technical education are heavily Head of Research, EngineeringUK began. In light of the current and rapidly changing educational reliant on employers and may not have considered the Aimee Higgins environment, EngineeringUK has not sought to update our specific requirements of engineering. It will be even harder to Director of Employers and Partnerships, The Careers & findings. -

Not for People Like Me?” Under-Represented Groups in Science, Technology and Engineering a Summary of the Evidence: the Facts, the Fiction and What We Should Do Next

Sponsored by a campaign to promote women in science, technology W I S E and engineering “Not for people like me?” Under-represented groups in science, technology and engineering A summary of the evidence: the facts, the fiction and what we should do next Author Professor Averil Macdonald South East Physics Network November 2014 W I S E Contents 3 Foreword 5 Introduction 6 Highlights A summary of evidence on STEM uptake by under-represented groups: 8 Where are we? 11 Does it matter? 12 So why do students from some backgrounds reject physics and engineering? 1 5 If we want to focus on under-represented groups, how do they differ from the majority group – white middle class boys? 19 What are the important factors in influencing choice for under-represented groups? 21 What can be done to make STEM qualifications and careers more attractive? 25 What works and what doesn’t in schools? 26 The importance of self-identity and 10 types of scientist 29 Appendix: Recommendations from WISE about what works for girls 30 Women working in STEM: the changes from 2012 to 2014 2 “Not for people like me?” Under-represented groups in science, technology and engineering W I S E Foreword etwork Rail is delighted to be working To enable girls to picture themselves in STEM Nwith WISE and Professor Averil roles, we need to help them to reconcile the Macdonald, Diversity Lead for the South East conflict between their self-identity and their Physics Network, to help make STEM for perception of STEM careers. In the report Averil people like me. -

The State of Engineering Key Facts 2016

The Engineering UK report was produced with The engineering sector is the support of the members and fellows of the The state of engineering essential to the UK economy following Professional Engineering Institutions: Key facts 2016 Our revised long-term recommendations based upon BCS The Chartered Institute for IT Institution of Engineering Designers new analysis from this year’s Engineering UK 2016 British Institute of Non-Destructive Institution of Fire Engineers report show that we need: Testing Institution of Gas Engineers Chartered Institute of Plumbing & Managers • A doubling of the number of engineering and technology and other related & Heating Engineering STEM and non-STEM graduates who are known to enter engineering Institution of Lighting Professionals occupations. This is vital to meet the demand for future engineering graduates Chartered Institution of Water Institution of Mechanical Engineers and to meet the additional shortfall in physics teachers and engineering & Environmental Management Institution of Railway Signal Engineers lecturers needed to inspire future generations of talented engineers. Energy Institute Institution of Royal Engineers • A doubling of the number of young people studying GCSE physics as part Engineering Council Nuclear Institute of triple sciences or further additional science or equivalent and a growth Institute of Acoustics in the number of students studying physics A level (or equivalent) to equal Royal Aeronautical Society that of maths. This must have a particular focus on increasing the take-up -

The State of Engineering Key Facts 2018

Engineering UK 2018 was produced with the support of Challenges and the members and fellows of the following Professional The state of engineering recommendations Engineering Institutions: Key facts 2018 If modern engineering is to continue to provide its BCS, The Chartered Institute for IT Institution of Lighting enormous economic and social contributions to British Institute of Non- Professionals (ILP) the United Kingdom, it is of critical importance that Destructive Testing (BINDT) Institute of Marine Engineering, Science & Technology (IMarEST) the engineering community work alongside the Chartered Institution of Building government and educational sector to address Services Engineers (CIBSE) Institution of Mechanical Chartered Institution of Highways Engineers (IMechE) the skills shortage. & Transportation (CIHT) Institute of Measurement and Chartered Institute of Plumbing Control (InstMC) Challenges and Heating Engineering (CIPHE) Institution of Royal Engineers • Too few STEM teachers Chartered Institution of Water (InstRE) • Limited access to STEM careers activity and Environmental Management Institute of Acoustics (IOA) (CIWEM) • Too few women becoming engineers Institute of Materials, Minerals Energy Institute (EI) and Mining (IOM3) • Too little home grown talent Institution of Agricultural Institute of Physics (IOP) • Too little understanding of apprenticeships Engineers (IAgrE) Institute of Physics and Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) Engineering in Medicine (IPEM) Recommendations Institution of Chemical Engineers Institution -

Assessing the Economic Returns of Engineering Research and Postgraduate Training in the UK

March 2015 Assessing the economic returns of engineering research and postgraduate training in the UK Final report www.technopolis-group.com Assessing the economic returns of engineering research and postgraduate training in the UK Final report technopolis |group|, March, 2015 Cristina Rosemberg, Paul Simmonds, Xavier Potau, Kristine Farla, Tammy Sharp, Martin Wain, Oliver Cassagneau-Francis and Helena Kovacs Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary 1 2. Introduction 4 2.1 Scope of the study 4 2.2 Defining engineering 4 3. Engineering contribution to the UK economy 6 3.1 Engineering contribution to the UK economy 6 3.1.1 Engineers are present across all economic sectors 6 3.1.2 Pervasiveness translates into a high contribution to UK GVA 8 3.2 Engineers as drivers of innovation and competitiveness 10 3.2.1 Engineers are highly valued by the labour market 10 3.2.2 High concentrations of engineers are linked with high levels of innovation10 3.2.3 Higher innovation and productivity leads to higher competitiveness 13 3.3 Engineers produce high quality research 14 3.3.1 The UK produces world leading engineering research 14 3.3.2 The UK has numerous engineering-related centres of excellence 17 3.3.3 This academic excellence translates into tangible economic benefits 19 3.3.4 Engineering research attracts inward investments 26 4. Engineering’s contributions to policy and public services 28 4.1 Engineers are crucial to the operation of many areas of government 28 4.2 Engineering research plays a key role in policy and public services 30 5. -

Delivering STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) Skills for the Economy

A picture of the National Audit Office logo Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy Department for Education Delivering STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) skills for the economy HC 716 SESSION 2017–2019 17 JANUARY 2018 Our vision is to help the nation spend wisely. Our public audit perspective helps Parliament hold government to account and improve public services. The National Audit Office scrutinises public spending for Parliament and is independent of government. The Comptroller and Auditor General (C&AG), Sir Amyas Morse KCB, is an Officer of the House of Commons and leads the NAO. The C&AG certifies the accounts of all government departments and many other public sector bodies. He has statutory authority to examine and report to Parliament on whether departments and the bodies they fund, nationally and locally, have used their resources efficiently, effectively, and with economy. The C&AG does this through a range of outputs including value-for-money reports on matters of public interest; investigations to establish the underlying facts in circumstances where concerns have been raised by others or observed through our wider work; and landscape reviews to aid transparency and good practice guides. Our work ensures that those responsible for the use of public money are held to account and helps government to improve public services, leading to audited savings of £734 million in 2016. Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy Department for -

Educating Tomorrow's Engineers

House of Commons Science and Technology Committee Educating tomorrow’s engineers: the impact of Government reforms on 14–19 education Seventh Report of Session 2012–13 HC 665 House of Commons Science and Technology Committee Educating tomorrow’s engineers: the impact of Government reforms on 14–19 education Seventh Report of Session 2012–13 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Additional written evidence is contained in Volume II, available on the Committee website at www.parliament.uk/science Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 30 January 2013 HC 665 Published on 8 February 2013 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 Science and Technology Committee The Science and Technology Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Government Office for Science and associated public bodies. Current membership Andrew Miller (Labour, Ellesmere Port and Neston) (Chair) Caroline Dinenage (Conservative, Gosport) Jim Dowd (Labour, Lewisham West and Penge) Stephen Metcalfe (Conservative, South Basildon and East Thurrock) David Morris (Conservative, Morecambe and Lunesdale) Stephen Mosley (Conservative, City of Chester) Pamela Nash (Labour, Airdrie and Shotts) Sarah Newton (Conservative, Truro and Falmouth) Graham Stringer (Labour, Blackley and Broughton) Hywel Williams (Plaid Cymru, Arfon) Roger Williams (Liberal Democrat, Brecon and Radnorshire) The following members were also members of the committee during the parliament: Gavin Barwell (Conservative, Croydon Central) Gareth Johnson (Conservative, Dartford) Gregg McClymont (Labour, Cumbernauld, Kilsyth and Kirkintilloch East) Stephen McPartland (Conservative, Stevenage) Jonathan Reynolds (Labour/Co-operative, Stalybridge and Hyde) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental Select Committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No.152. -

The UK STEM Education Landscape

Royal Academy of Engineering Identity guidelines Introduction Version 1.0 > The logo The key elements Applying the elements The logo 02 Colour variants Our logo is available in a series of The logo must only appear in the colour different colour versions to enable combinations shown on this page. Never flexibility and creativity in application. attempt to recreate the logo and always They are to be used freely and not to use the master artwork supplied. categorise communications. Special use logo varient The silver version of our logo can be created in CMYK or a metallic can be used. This logo is restricted for use by the President and CEO for their personal communications such as business cards, letter heads and invitations. The UK STEM Education Landscape May 2016 The UK STEM Education Landscape A report for the Lloyd’s Register Foundation from the Royal Academy of Engineering Education and Skills Committee May 2016 © Royal Academy of Engineering 2016 Available to download from: www.raeng.org.uk/stemlandscape ISBN: 978-1-909327-25-2 Cover photo: Royal Academy of Engineering Authors Dr Rhys Morgan and Chris Kirby with additional research undertaken by Ms Aleksandra Stamenkovic For further information, please contact: [email protected] Acknowledgements The Royal Academy of Engineering is indebted to the Lloyd’s Register Foundation for its generous support that has enabled this study to be carried out. The Academy is also grateful to the many organisations and individuals listed at the back of this report who provided guidance and feedback with the development of the data gathering for this study. -

Engineering the Future – a Vision for UK Engineering

RAEng News Spring 2010 News Spring 2010 President’s column 2 making things better campaign launch 3 SET for Britain 4 Awards 5 Policy and Public Affairs 6 International 8 New Year Honours 9 News of Fellows 9 Education 10 Obituaries 12 Spring events 2010 12 Engineering the future – a vision for UK engineering Over recent months, the Academy has been working closely with its partners in the Engineering the future alliance to produce a shared vision for engineering. This has been circulated to the major political parties’ election manifesto writing teams. The vision document identifies the following five key priorities for a thriving UK economy, based on engineering innovation that builds on our national strengths and addresses the grand challenges of the 21st century. 1. Sustaining and encouraging investment in the skills for the future. World-class engineering and technology skills are critically important if the UK is to compete internationally and create the high-value, technology-based industries of the future. Engineering at all levels is underpinned by the science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) taught at school. We call for a greater focus on STEM subjects with young people taught by STEM specialists and given access to focused careers advice. The wide range of pathways into the engineering profession, from 14-19 Diplomas to degree courses, must be supported and industry needs encouragement to provide apprenticeships and graduate training. The right level of investment in university engineering departments must be ensured to maintain the UK’s status as a world leader in engineering and science higher education. -

Press Release

Royal Academy of Engineering Royal Aeronautical T: +44 (0)20 7670 4300 Prince Philip House Society E: [email protected] 3 Carlton House Terrace No. 4 Hamilton www.aerosociety.com London SW1Y 5DG Place 0207 766 0636 London W1J 7BQ [email protected] United Kingdom PRESS RELEASE EMBARGOED until 00.01 on Tuesday 27 August 2019 ENGINEERING PROFESSION CALLS FOR ACTION TO SECURE THE UK’S FUTURE ECONOMY AND SOCIETY. The National Engineering Policy Centre, which represents nearly half a million UK engineers, has published a manifesto for a prosperous and secure economy and society, calling on government to work with them to invest in skills, innovation, digital and traditional infrastructure, and clean energy technologies. Backed by the UK’s leading engineering organisations, Engineering priorities for our future economy and society highlights critical policy recommendations to enhance the UK’s status as a world-leading innovation and engineering hub, ahead of the forthcoming spending review, the UK’s exit from the EU and a possible general election. This is the first joint publication by the National Engineering Policy Centre, an ambitious new partnership between 39 UK engineering organisations, led by the Royal Academy of Engineering. The National Engineering Policy Centre was established to give policymakers access to the best independent advice, skills and expertise of the engineering profession, which generates £420.5 billion of UK GVA and employs over 5.8 million people. It aims to apply engineers’ problem solving skills to some of the biggest problems the UK faces today. This engineering manifesto includes 20 actions across five key policy areas: • Skills: Implement the recommendations of the Perkins Review, which sets out actions to ensure an adequate supply of engineering talent for our nation, to secure the engineering skills needed for the future.