Copyright by Rebecca Anne Montes 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Journal of the Central Plains Volume 37, Number 3 | Autumn 2014

Kansas History A Journal of the Central Plains Volume 37, Number 3 | Autumn 2014 A collaboration of the Kansas Historical Foundation and the Department of History at Kansas State University A Show of Patriotism German American Farmers, Marion County, June 9, 1918. When the United States formally declared war against Onaga. There are enough patriotic citizens of the neighborhood Germany on April 6, 1917, many Americans believed that the to enforce the order and they promise to do it." Wamego mayor war involved both the battlefield in Europe and a fight against Floyd Funnell declared, "We can't hope to change the heart of disloyal German Americans at home. Zealous patriots who the Hun but we can and will change his actions and his words." considered German Americans to be enemy sympathizers, Like-minded Kansans circulated petitions to protest schools that spies, or slackers demanded proof that immigrants were “100 offered German language classes and churches that delivered percent American.” Across the country, but especially in the sermons in German, while less peaceful protestors threatened Midwest, where many German settlers had formed close- accused enemy aliens with mob violence. In 1918 in Marion knit communities, the public pressured schools, colleges, and County, home to a thriving Mennonite community, this group churches to discontinue the use of the German language. Local of German American farmers posed before their tractor and newspapers published the names of "disloyalists" and listed threshing machinery with a large American flag in an attempt their offenses: speaking German, neglecting to donate to the to prove their patriotism with a public display of loyalty. -

Hispanic Archival Collections Houston Metropolitan Research Cent

Hispanic Archival Collections People Please note that not all of our Finding Aids are available online. If you would like to know about an inventory for a specific collection please call or visit the Texas Room of the Julia Ideson Building. In addition, many of our collections have a related oral history from the donor or subject of the collection. Many of these are available online via our Houston Area Digital Archive website. MSS 009 Hector Garcia Collection Hector Garcia was executive director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations, Diocese of Galveston-Houston, and an officer of Harris County PASO. The Harris County chapter of the Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations (PASO) was formed in October 1961. Its purpose was to advocate on behalf of Mexican Americans. Its political activities included letter-writing campaigns, poll tax drives, bumper sticker brigades, telephone banks, and community get-out-the- vote rallies. PASO endorsed candidates supportive of Mexican American concerns. It took up issues of concern to Mexican Americans. It also advocated on behalf of Mexican Americans seeking jobs, and for Mexican American owned businesses. PASO produced such Mexican American political leaders as Leonel Castillo and Ben. T. Reyes. Hector Garcia was a member of PASO and its executive secretary of the Office of Community Relations. In the late 1970's, he was Executive Director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations for the Diocese of Galveston-Houston. The collection contains some materials related to some of his other interests outside of PASO including reports, correspondence, clippings about discrimination and the advancement of Mexican American; correspondence and notices of meetings and activities of PASO (Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations of Harris County. -

Houston Chronicle Index to Mexican American Articles, 1901-1979

AN INDEX OF ITEMS RELATING TO MEXICAN AMERICANS IN HOUSTON AS EXTRACTED FROM THE HOUSTON CHRONICLE This index of the Houston Chronicle was compiled in the Spring and summer semesters of 1986. During that period, the senior author, then a Visiting Scholar in the Mexican American Studies Center at the University of Houston, University Park, was engaged in researching the history of Mexican Americans in Houston, 1900-1980s. Though the research tool includes items extracted for just about every year between 1901 (when the Chronicle was established) and 1970 (the last year searched), its major focus is every fifth year of the Chronicle (1905, 1910, 1915, 1920, and so on). The size of the newspaper's collection (more that 1,600 reels of microfilm) and time restrictions dictated this sampling approach. Notes are incorporated into the text informing readers of specific time period not searched. For the era after 1975, use was made of the Annual Index to the Houston Post in order to find items pertinent to Mexican Americans in Houston. AN INDEX OF ITEMS RELATING TO MEXICAN AMERICANS IN HOUSTON AS EXTRACTED FROM THE HOUSTON CHRONICLE by Arnoldo De Leon and Roberto R. Trevino INDEX THE HOUSTON CHRONICLE October 22, 1901, p. 2-5 Criminal Docket: Father Hennessey this morning paid a visit to Gregorio Cortez, the Karnes County murderer, to hear confession November 4, 1901, p. 2-3 San Antonio, November 4: Miss A. De Zavala is to release a statement maintaining that two children escaped the Alamo defeat. History holds that only a woman and her child survived the Alamo battle November 4, 1901, p. -

Felix Tijerina

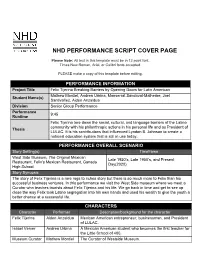

NHD PERFORMANCE SCRIPT COVER PAGE Please Note: All text in this template must be in 12 point font. Times New Roman, Arial, or Calibri fonts accepted. PLEASE make a copy of this template before editing. PERFORMANCE INFORMATION Project Title Felix Tijerina Breaking Barriers by Opening Doors for Latin American Mathew Montiel, Andrea Urbina, Monserrat Sandoval-Malherbe, Joel Student Name(s) Santivañez, Aiden Anzaldua Division Senior Group Performance Performance 9:45 Runtime Felix Tijerina tore down the social, cultural, and language barriers of the Latino community with his philanthropic actions in his personal life and as President of Thesis LULAC. It is his contributions that influenced Lyndon B. Johnson to create a national education system that is still in use today. PERFORMANCE OVERALL SCENARIO Story Setting(s) Timeframe West Side Museum, The Original Mexican Late 1920’s, Late 1950’s, and Present Restaurant, Felix’s Mexican Restaurant, Ganado Day(2020) High School Story Synopsis The story of Felix Tijerina is a rare rags to riches story but there is so much more to Felix than his successful business ventures. In this performance we visit the West Side museum where we meet a Curator who teaches tourists about Felix Tijerina and his life. We go back in time and get to see up close the way Felix took Latino segregation into his own hands and used his wealth to give the youth a better chance at a successful life. CHARACTERS Character Performer Description/background for the character Felix Tijerina Aiden Anzaldua Mexican American entrepreneur, businessman, and President of LULAC. Isabel Verver Andrea Urbina A Mexican American student who becomes the first teacher for the Little School of 400. -

THE ROLE of THIRD-PARTY FUNDERS in the DEVELOPMENT of MEXICAN AMERICAN INTEREST GROUP ADVOCACY by Devin Fernandes

CONSTRUCTING THE CAUSE: THE ROLE OF THIRD-PARTY FUNDERS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF MEXICAN AMERICAN INTEREST GROUP ADVOCACY by Devin Fernandes A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY © Devin Fernandes 2018 All rights reserved ABSTRACT For the last 25 years, scholars have raised alarms over the disappearance of local civic membership organizations since the 1960s and a concomitant explosion of third-party-funded, staff-dominated, professional advocacy organizations. This change is said to contribute to long- term declines in civic and political participation, particularly among minorities and low income Americans, and by extension, diminished electoral fortunes of the Democratic Party. Rather than mobilize mass publics and encourage their political participation, the new, largely progressive advocacy groups finance themselves independently through foundation grant money and do most of their work in Washington where they seek behind the scenes influence with unelected branches of government. However, in seeking to understand this transition “from membership to advocacy,” most current scholarship focuses on the socio-political factors that made it possible. We have little understanding of the internal dynamics sustaining individual organizations themselves to account for why outside-funded groups are able to emerge and thrive or the ways in which dependence on external subsidies alters their operating incentives. To address this hole in the literature, the dissertation engages in a theory-building effort through a case study analysis of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF), founded in 1968. Drawing on archival materials from MALDEF and its primary benefactor, the Ford Foundation, the dissertation opens the black box of internal decision-making to understand in real time how resource dependence on non-beneficiaries shaped the maintenance calculus of its leaders and in turn, group behavior. -

Development Plat Submittal Requirements

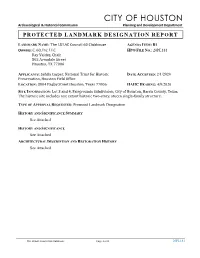

CITY OF HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission _ __ Planning and Development Department PROTECTED LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT LANDMARK NAME: The LULAC Council 60 Clubhouse AGENDA ITEM: B1 OWNERS: C. 60, Inc. LLC HPO FILE NO.: 20PL181 Ray Valdez, Chair 502 Avondale Street Houston, TX 77006 APPLICANTS: Sehila Casper, National Trust for Historic DATE ACCEPTED: 2/1/2020 Preservation, Houston Field Office LOCATION: 3004 Bagby Street Houston, Texas 77006 HAHC HEARING: 4/9/2020 SITE INFORMATION: Lot 3 and 4, Fairgrounds Subdivision, City of Houston, Harris County, Texas. The historic site includes one extant historic two-story, stucco single-family structure. TYPE OF APPROVAL REQUESTED: Protected Landmark Designation HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE SUMMARY See Attached HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE See Attached ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTION AND RESTORATION HISTORY See Attached The LULAC Council 60 Clubhouse Page 1 of 3 20PL181 CITY OF HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission _ __ Planning and Development Department APPROVAL CRITERIA FOR LANDMARK DESIGNATION Sec. 33-224. Criteria for designation (a) The HAHC, in making recommendations with respect to designation, and the city council, in making a designation, shall consider one or more of the following criteria, as appropriate for the type of designation: S NA S - satisfies D - does not satisfy NA - not applicable (1) Whether the building, structure, object, site or area possesses character, interest or value as a visible reminder of the development, heritage, and cultural and ethnic diversity -

MSS 009 Hector Garcia Collection MSS 0093 Alfonso Vazquez

Hispanic Archival Collections Please note that not all of our Finding Aids are available online. If you would like to know about an inventory for a specific collection please call or visit the Texas Room of the Julia Ideson Building. In addition, many of our collections have a related oral history from the donor or subject of the collection. Many of these are available online via our Houston Area Digital Archive website. MSS 009 Hector Garcia Collection Hector Garcia was executive director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations, Diocese of Galveston-Houston, and an officer of Harris County PASO. The Harris County chapter of the Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations (PASO) was formed in October 1961. Its purpose was to advocate on behalf of Mexican Americans. Its political activities included letter-writing campaigns, poll tax drives, bumper sticker brigades, telephone banks, and community get-out-the- vote rallies. PASO endorsed candidates supportive of Mexican American concerns. It took up issues of concern to Mexican Americans. It also advocated on behalf of Mexican Americans seeking jobs, and for Mexican American owned businesses. PASO produced such Mexican American political leaders as Leonel Castillo and Ben. T. Reyes. Hector Garcia was a member of PASO and its executive secretary of the Office of Community Relations. In the late 1970's, he was Executive Director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations for the Diocese of Galveston-Houston. The collection contains some materials related to some of his other interests outside of PASO including reports, correspondence, clippings about discrimination and the advancement of Mexican American; correspondence and notices of meetings and activities of PASO (Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations of Harris County. -

A Guide to Researching Your Neighborhood History

A Guide to Researching Your Neighborhood History Prepared by the Neighborhood Histories Committee of the Houston History Association Contributors Betty Trapp Chapman Jo Collier Dick Dickerson Diana DuCroz MJ Figard Marks Hinton Penny Jones Robert Marcom Carol McDavid Randy Pace Gail Rosenthal Debra Blacklock Sloan Courtney Spillane Pam Young © Houston History Association, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..................................................... ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. GETTING S TARTED ....................................................................................... 5 Why Do a Neighborhood History Project Now? ..................................................................5 Some Ideas for a Neighborhood History Project ..................................................................5 Who can do a Neighborhood History Project? .....................................................................5 How to Get Started..............................................................................................................5 Historical Resources............................................................................................................6 RESEARCH T OOLS AND TIPS FOR USING L OCAL RESOURCES ................................. 7 Introduction.........................................................................................................................7 Getting Started ....................................................................................................................7 Using -

A Mexican-American Fight for Equal Access and Its Impact on State Policy

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History History, Department of Spring 5-2013 The Little School of the 400: A Mexican-American Fight for Equal Access and its Impact on State Policy Erasmo Vázquez Ríos University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, and the Other Education Commons Vázquez Ríos, Erasmo, "The Little School of the 400: A Mexican-American Fight for Equal Access and its Impact on State Policy" (2013). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History. 58. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss/58 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE LITTLE SCHOOL OF THE 400: A MEXICAN-AMERICAN FIGHT FOR EQUAL ACCESS AND ITS IMPACT ON STATE POLICY by Erasmo Vázquez Ríos A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: History Under the Supervision of Professor James A. Garza Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2013 THE LITTLE SCHOOL OF THE 400: A MEXICAN-AMERICAN FIGHT FOR EQUAL ACCESS AND ITS IMPACT ON STATE POLICY Erasmo Vázquez Ríos, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2013 Advisor: James A. Garza Founded in 1957, the Little School of the 400 (LS400) was a Mexican-American led effort to acculturate and assimilate Mexican schoolchildren in Texas to the dominant Anglo-led society. -

Hello Neighbors!! P.O. Box

Hello Neighbors!! BOARD CONTACTS elcome to the April ing the last couple of weeks, I have been Wissue of the Hyde noticing many of you out there preparing PRESIDENT Park United Newsletter. your yards, and getting them ready for Trevor Eade [email protected] Before I update you with Spring. If you would like to nominate your some of the activities yard, or a neighbor’s yard, please email VICE PRESIDENT that are in the works, I me at [email protected]. George Sroka wanted to quickly recap I am also pleased to announce that this [email protected] our March member- isn’t limited to single family homes. This SECRETARY ship meeting. We were now extends to all dwelling types (Con- Macy Bodenhamer thrilled to have Council Member Wanda dos, Town Houses, Businesses, etc). Who [email protected] Adams and HPD Officer Wayne Pate. is April’s Yard of the Month? See inside TREASURER Among the important topics of discussion (this was my nomination). Carol Brownstein were recycling, redistricting and best prac- [email protected] tices for keeping your home and property Resident of the Month for April 2011 is OTHER CONTACTS safe. For more details, please read the Sec- a well-known advocate of our neighbor- retary’s minutes. hood, Mr. David Centanni. David has DEED RESTRICTIONS done so much for our community, in Stephen Marchione [email protected] During the month of April, we recognize terms of his volunteerism with the Deed Earth Day 2011, and your Hyde Park Board Restrictions committee and his continued MEMBERSHIP would like to celebrate this by holding a support as our Webmaster. -

Book Faire Layout V 4 0.Pdf

2016 2016 Keynote Speakers Jerry Coyne Jerry A. Coyne is a Professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolution at the University of Chicago. He received a B.S. in Biology from the College of William and Mary and a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology at Har- vard University. After a postdoctoral fellowship at The University of California at Davis, he took his first aca- demic position as assistant professor in the Department of Zoology at The University of Maryland. In 1996 he joined the faculty of The University of Chi- cago and has been there ever since. Coyne’s work has been largely concerned with the genetics of species differences, aimed at understanding the evolu- tionary processes that produce new species. He has written 115 scientific papers and more than 130 popular articles, book reviews, and columns, as well as a scholarly book about his research area—Speciation, co-authored with H. Allen Orr—and a trade book about the evidence for evolution—Why Evolution is True, which was a New York Times best- seller. His latest book, Faith vs. Fact: Why Science and Religion are Incompatible (Viking/Penguin Random House) appeared in May of 2015. Coyne is a contrib- utor The New York Times, The New Republic, The Times Literary Supplement, The Guardian, Slate, The Nation, USA Today, and other popular periodi- cals. FAITH VS. FACT WHY SCIENCE AND RELIGION ARE COMPATIBLE 2 3 2016 Author Biographies Daniel Adams Dale Ahlquist Daniel Adams (b. 1956, Miami, FL) is a Professor Dale Ahlquist is President of the American Chesterton of Music at Texas Southern University in Houston. -

La Colonia Mexicana

Children from the Santa Teresita catechetical center in the Heights, accompanied by catequistas from Our Lady of Guadalupe, Bernadina Gonzales, Porfiria Gonzales (sisters), and Petra Sanchez, circa 1935. Photo courtesy of Petra Guillen. La Colonia Mexicana: A History of Mexican Americans in Houston By Jesus Jesse Esparza In 1836, newcomers from the United States along with their One of the earliest Mexican American neighborhoods Tejano (Texas Mexicans) allies, took up arms against the to emerge in Second Ward was El Alacrán (the scorpion). Mexican government and successfully seceded from that na- Another was Magnolia Park, although it grew farther east tion.1 Following the Battle of San Jacinto, which ended the along the Houston Ship Channel. North of downtown in the Texas Revolution, Texians (Anglo Texans) ordered Mexican Fifth Ward, Mexican Americans established a residential prisoners to clean the swampland on which Houston would zone, and about 100 Mexican American families settled be built. Afterwards, most were sent home, but many in the Heights area. Most of the early Mexican American stayed, creating the starting point of early Mexican settle- neighborhoods were poor areas without paved streets, run- ment in the Houston region.2 ning water, gas, or electric services. These amenities were gradually added after the areas experienced permanent Community Growth & Formation, 1900-1930 settlement and growth.4 Between 1836 and 1900, Mexicanos lived on the outskirts of Mexican Americans worked in most industries and Houston, coming into town mostly to find work. By 1900, established a variety of businesses, laying the foundation they began to settle permanently within the city, occupying for a bustling Mexican American economy.