A Mexican-American Fight for Equal Access and Its Impact on State Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Journal of the Central Plains Volume 37, Number 3 | Autumn 2014

Kansas History A Journal of the Central Plains Volume 37, Number 3 | Autumn 2014 A collaboration of the Kansas Historical Foundation and the Department of History at Kansas State University A Show of Patriotism German American Farmers, Marion County, June 9, 1918. When the United States formally declared war against Onaga. There are enough patriotic citizens of the neighborhood Germany on April 6, 1917, many Americans believed that the to enforce the order and they promise to do it." Wamego mayor war involved both the battlefield in Europe and a fight against Floyd Funnell declared, "We can't hope to change the heart of disloyal German Americans at home. Zealous patriots who the Hun but we can and will change his actions and his words." considered German Americans to be enemy sympathizers, Like-minded Kansans circulated petitions to protest schools that spies, or slackers demanded proof that immigrants were “100 offered German language classes and churches that delivered percent American.” Across the country, but especially in the sermons in German, while less peaceful protestors threatened Midwest, where many German settlers had formed close- accused enemy aliens with mob violence. In 1918 in Marion knit communities, the public pressured schools, colleges, and County, home to a thriving Mennonite community, this group churches to discontinue the use of the German language. Local of German American farmers posed before their tractor and newspapers published the names of "disloyalists" and listed threshing machinery with a large American flag in an attempt their offenses: speaking German, neglecting to donate to the to prove their patriotism with a public display of loyalty. -

Hispanic Archival Collections Houston Metropolitan Research Cent

Hispanic Archival Collections People Please note that not all of our Finding Aids are available online. If you would like to know about an inventory for a specific collection please call or visit the Texas Room of the Julia Ideson Building. In addition, many of our collections have a related oral history from the donor or subject of the collection. Many of these are available online via our Houston Area Digital Archive website. MSS 009 Hector Garcia Collection Hector Garcia was executive director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations, Diocese of Galveston-Houston, and an officer of Harris County PASO. The Harris County chapter of the Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations (PASO) was formed in October 1961. Its purpose was to advocate on behalf of Mexican Americans. Its political activities included letter-writing campaigns, poll tax drives, bumper sticker brigades, telephone banks, and community get-out-the- vote rallies. PASO endorsed candidates supportive of Mexican American concerns. It took up issues of concern to Mexican Americans. It also advocated on behalf of Mexican Americans seeking jobs, and for Mexican American owned businesses. PASO produced such Mexican American political leaders as Leonel Castillo and Ben. T. Reyes. Hector Garcia was a member of PASO and its executive secretary of the Office of Community Relations. In the late 1970's, he was Executive Director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations for the Diocese of Galveston-Houston. The collection contains some materials related to some of his other interests outside of PASO including reports, correspondence, clippings about discrimination and the advancement of Mexican American; correspondence and notices of meetings and activities of PASO (Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations of Harris County. -

American Jewish Yearbook

JEWISH STATISTICS 277 JEWISH STATISTICS The statistics of Jews in the world rest largely upon estimates. In Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, and a few other countries, official figures are obtainable. In the main, however, the num- bers given are based upon estimates repeated and added to by one statistical authority after another. For the statistics given below various authorities have been consulted, among them the " Statesman's Year Book" for 1910, the English " Jewish Year Book " for 5670-71, " The Jewish Ency- clopedia," Jildische Statistik, and the Alliance Israelite Uni- verselle reports. THE UNITED STATES ESTIMATES As the census of the United States has, in accordance with the spirit of American institutions, taken no heed of the religious convictions of American citizens, whether native-born or natural- ized, all statements concerning the number of Jews living in this country are based upon estimates. The Jewish population was estimated— In 1818 by Mordecai M. Noah at 3,000 In 1824 by Solomon Etting at 6,000 In 1826 by Isaac C. Harby at 6,000 In 1840 by the American Almanac at 15,000 In 1848 by M. A. Berk at 50,000 In 1880 by Wm. B. Hackenburg at 230,257 In 1888 by Isaac Markens at 400,000 In 1897 by David Sulzberger at 937,800 In 1905 by "The Jewish Encyclopedia" at 1,508,435 In 1907 by " The American Jewish Year Book " at 1,777,185 In 1910 by " The American Je\rish Year Book" at 2,044,762 DISTRIBUTION The following table by States presents two sets of estimates. -

Stirring the American Melting Pot: Middle Eastern Immigration, the Progressives, and the Legal Construction of Whiteness, 1880-1

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2013 Stirring the American Melting Pot: Middle Eastern Immigration, the Progressives and the Legal Construction of Whiteness, 1880-1924 Richard Soash Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES STIRRING THE AMERICAN MELTING POT: MIDDLE EASTERN IMMIGRATION, THE PROGRESSIVES AND THE LEGAL CONSTRUCTION OF WHITENESS, 1880-1924 By RICHARD SOASH A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2013 Richard Soash defended this thesis on March 7, 2013. The members of the supervisory committee were: Jennifer Koslow Professor Directing Thesis Suzanne Sinke Committee Member Peter Garretson Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To my Grandparents: Evan & Verena Soash Richard & Patricia Fluck iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am extremely thankful for both the academic and financial support that Florida State University has provided for me in the past two years. I would also like to express my gratitude to the FSU History Department for giving me the opportunity to pursue my graduate education here. My academic advisor and committee members – Dr. Koslow, Dr. Sinke, and Dr. Garretson – have been wonderful teachers and mentors during my time in the Master’s Program; I greatly appreciate their patience, humor, and knowledge, both inside and outside of the classroom. -

The Syrian Community in New Castle and Its Unique Alawi Component, 1900-1940 Anthony B

The Syrian Community in New Castle and Its Unique Alawi Component, 1900-1940 Anthony B. Toth L Introduction and immigration are two important and intertwined phenomena in Pennsylvania's history from 1870 to INDUSTRIALIZATIONWorld War II.The rapid growth of mining, iron and steel pro- duction, manufacturing, and railroads during this period drew millions of immigrants. In turn, the immigrants had a significant effect on their towns and cities. The largest non-English-speaking— groups to jointhe industrial work force — the Italians and Poles have been the sub- jects of considerable scholarly attention. 1 Relatively little, however, has been published about many of the smaller but still significant groups that took part in the "new immigration/' New Castle's Syrian community is one such smaller group. 2 In a general sense, it is typical of other Arabic-speaking immigrant com- munities which settled inAmerican industrial centers around the turn of the century — Lawrence, Fall River, and Springfield, Mass.; Provi- Writer and editor Anthony B. Toth earned his master's degree in Middle East history from Georgetown University. He performed the research for this article while senior writer for the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee Re- search Institute. He has also written articles on the Arab-American communities in Jacksonville, Florida, and Worcester, Massachusetts. —Editor 1 Anyone researching the history of immigrants and Pennsylvania industry cannot escape the enlightening works of John E.Bodnar, who focuses main- ly on the Polish and Italian experiences. In particular, see his Workers' World: Kinship, Community and Protest in an Industrial Society, 1900- 1940 (Baltimore, 1982); Immigration and Industrialization: Ethnicity in an American MillTown, 1870-1940 (Pittsburgh, —1977); and, with Roger Simon and Michael P. -

Houston Chronicle Index to Mexican American Articles, 1901-1979

AN INDEX OF ITEMS RELATING TO MEXICAN AMERICANS IN HOUSTON AS EXTRACTED FROM THE HOUSTON CHRONICLE This index of the Houston Chronicle was compiled in the Spring and summer semesters of 1986. During that period, the senior author, then a Visiting Scholar in the Mexican American Studies Center at the University of Houston, University Park, was engaged in researching the history of Mexican Americans in Houston, 1900-1980s. Though the research tool includes items extracted for just about every year between 1901 (when the Chronicle was established) and 1970 (the last year searched), its major focus is every fifth year of the Chronicle (1905, 1910, 1915, 1920, and so on). The size of the newspaper's collection (more that 1,600 reels of microfilm) and time restrictions dictated this sampling approach. Notes are incorporated into the text informing readers of specific time period not searched. For the era after 1975, use was made of the Annual Index to the Houston Post in order to find items pertinent to Mexican Americans in Houston. AN INDEX OF ITEMS RELATING TO MEXICAN AMERICANS IN HOUSTON AS EXTRACTED FROM THE HOUSTON CHRONICLE by Arnoldo De Leon and Roberto R. Trevino INDEX THE HOUSTON CHRONICLE October 22, 1901, p. 2-5 Criminal Docket: Father Hennessey this morning paid a visit to Gregorio Cortez, the Karnes County murderer, to hear confession November 4, 1901, p. 2-3 San Antonio, November 4: Miss A. De Zavala is to release a statement maintaining that two children escaped the Alamo defeat. History holds that only a woman and her child survived the Alamo battle November 4, 1901, p. -

Comparing the Basque Diaspora

COMPARING THE BASQUE DIASPORA: Ethnonationalism, transnationalism and identity maintenance in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Peru, the United States of America, and Uruguay by Gloria Pilar Totoricagiiena Thesis submitted in partial requirement for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2000 1 UMI Number: U145019 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U145019 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Theses, F 7877 7S/^S| Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully acknowledge the supervision of Professor Brendan O’Leary, whose expertise in ethnonationalism attracted me to the LSE and whose careful comments guided me through the writing of this thesis; advising by Dr. Erik Ringmar at the LSE, and my indebtedness to mentor, Professor Gregory A. Raymond, specialist in international relations and conflict resolution at Boise State University, and his nearly twenty years of inspiration and faith in my academic abilities. Fellowships from the American Association of University Women, Euskal Fundazioa, and Eusko Jaurlaritza contributed to the financial requirements of this international travel. -

Felix Tijerina

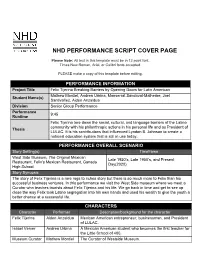

NHD PERFORMANCE SCRIPT COVER PAGE Please Note: All text in this template must be in 12 point font. Times New Roman, Arial, or Calibri fonts accepted. PLEASE make a copy of this template before editing. PERFORMANCE INFORMATION Project Title Felix Tijerina Breaking Barriers by Opening Doors for Latin American Mathew Montiel, Andrea Urbina, Monserrat Sandoval-Malherbe, Joel Student Name(s) Santivañez, Aiden Anzaldua Division Senior Group Performance Performance 9:45 Runtime Felix Tijerina tore down the social, cultural, and language barriers of the Latino community with his philanthropic actions in his personal life and as President of Thesis LULAC. It is his contributions that influenced Lyndon B. Johnson to create a national education system that is still in use today. PERFORMANCE OVERALL SCENARIO Story Setting(s) Timeframe West Side Museum, The Original Mexican Late 1920’s, Late 1950’s, and Present Restaurant, Felix’s Mexican Restaurant, Ganado Day(2020) High School Story Synopsis The story of Felix Tijerina is a rare rags to riches story but there is so much more to Felix than his successful business ventures. In this performance we visit the West Side museum where we meet a Curator who teaches tourists about Felix Tijerina and his life. We go back in time and get to see up close the way Felix took Latino segregation into his own hands and used his wealth to give the youth a better chance at a successful life. CHARACTERS Character Performer Description/background for the character Felix Tijerina Aiden Anzaldua Mexican American entrepreneur, businessman, and President of LULAC. Isabel Verver Andrea Urbina A Mexican American student who becomes the first teacher for the Little School of 400. -

Teaching Immigration with the Immigrant Stories Project LESSON PLANS

Teaching Immigration with the Immigrant Stories Project LESSON PLANS 1 Acknowledgments The Immigration History Research Center and The Advocates for Human Rights would like to thank the many people who contributed to these lesson plans. Lead Editor: Madeline Lohman Contributors: Elizabeth Venditto, Erika Lee, and Saengmany Ratsabout Design: Emily Farell and Brittany Lynk Volunteers and Interns: Biftu Bussa, Halimat Alawode, Hannah Mangen, Josefina Abdullah, Kristi Herman Hill, and Meredith Rambo. Archival Assistance and Photo Permissions: Daniel Necas A special thank you to the Immigration History Research Center Archives for permitting the reproduction of several archival photos. The lessons would not have been possible without the generous support of a Joan Aldous Diversity Grant from the University of Minnesota’s College of Liberal Arts. Immigrant Stories is a project of the Immigration History Research Center at the University of Minnesota. This work has been made possible through generous funding from the Digital Public Library of America Digital Hubs Pilot Project, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Humanities. About the Immigration History Research Center Founded in 1965, the University of Minnesota's Immigration History Research Center (IHRC) aims to transform how we understand immigration in the past and present. Along with its partner, the IHRC Archives, it is North America's oldest and largest interdisciplinary research center and archives devoted to preserving and understanding immigrant and refugee life. The IHRC promotes interdisciplinary research on migration, race, and ethnicity in the United States and the world. It connects U.S. immigration history research to contemporary immigrant and refugee communities through its Immigrant Stories project. -

Citizenship, Refugees, and the State: Bosnians, Southern Sudanese, and Social Service Organizations in Fargo, North Dakota"

CITIZENSHIP, REFUGEES, AND THE STATE: BOSNIANS, SOUTHERN SUDANESE, AND SOCIAL SERVICE ORGANIZATIONS IN FARGO, NORTH DAKOTA by JENNIFER LYNN ERICKSON A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Anthropology and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2010 11 University of Oregon Graduate School Confirmation of Approval and Acceptance of Dissertation prepared by: Jennifer Erickson Title: "Citizenship, Refugees, and the State: Bosnians, Southern Sudanese, and Social Service Organizations in Fargo, North Dakota" This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Doctor ofPhilosophy degree in the Department ofAnthropology by: Carol Silverman, Chairperson, Anthropology Sandra Morgen, Member, Anthropology Lynn Stephen, Member, Anthropology Susan Hardwick, Outside Member, Geography and Richard Linton, Vice President for Research and Graduate StudieslDean ofthe Graduate School for the University of Oregon. September 4,2010 Original approval signatures are on file with the Graduate School and the University of Oregon Libraries. 111 © 2010 Jennifer Lynn Erickson IV An Abstract ofthe Dissertation of Jennifer Lynn Erickson for the degree of Doctor ofPhilosophy in the Department ofAnthropology to be taken September 2010 Title: CITIZENSHIP, REFUGEES, AND THE STATE: BOSNIANS, SOUTHERN SUDANESE, AND SOCIAL SERVICE ORGAl~IZATIONS IN FARGO, NORTH DAKOTA Approved: _ Dr. Carol Silverman This dissertation is a comparative, ethnographic study ofSouthern Sudanese and Bosnian refugees and social service organizations in Fargo, North Dakota. I examine how refugee resettlement staff, welfare workers, and volunteers attempted to transform refugee clients into "worthy" citizens through neoliberal policies aimed at making them economically self-sufficient and independent from the state. -

THE ROLE of THIRD-PARTY FUNDERS in the DEVELOPMENT of MEXICAN AMERICAN INTEREST GROUP ADVOCACY by Devin Fernandes

CONSTRUCTING THE CAUSE: THE ROLE OF THIRD-PARTY FUNDERS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF MEXICAN AMERICAN INTEREST GROUP ADVOCACY by Devin Fernandes A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY © Devin Fernandes 2018 All rights reserved ABSTRACT For the last 25 years, scholars have raised alarms over the disappearance of local civic membership organizations since the 1960s and a concomitant explosion of third-party-funded, staff-dominated, professional advocacy organizations. This change is said to contribute to long- term declines in civic and political participation, particularly among minorities and low income Americans, and by extension, diminished electoral fortunes of the Democratic Party. Rather than mobilize mass publics and encourage their political participation, the new, largely progressive advocacy groups finance themselves independently through foundation grant money and do most of their work in Washington where they seek behind the scenes influence with unelected branches of government. However, in seeking to understand this transition “from membership to advocacy,” most current scholarship focuses on the socio-political factors that made it possible. We have little understanding of the internal dynamics sustaining individual organizations themselves to account for why outside-funded groups are able to emerge and thrive or the ways in which dependence on external subsidies alters their operating incentives. To address this hole in the literature, the dissertation engages in a theory-building effort through a case study analysis of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF), founded in 1968. Drawing on archival materials from MALDEF and its primary benefactor, the Ford Foundation, the dissertation opens the black box of internal decision-making to understand in real time how resource dependence on non-beneficiaries shaped the maintenance calculus of its leaders and in turn, group behavior. -

Designed to Supplement Eleventh Grade U.S. History Textbooks, The

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 258 854 SO 016 495 TITLE The Immigrant Experience: A Polish-American Model. Student Materials. INSTITUTION Social Studies Development %.enter, Bloomington, Ind. SPONS AGENCY Office of Elementary and Secondary Education (ED), Washington, DC. Ethnic Heritage Studies Program. # .PUB DATE Jan 83 CONTRACT G008100438 NOTE 79p.; For teacher's guide, see ED 230 .451. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Materials (For Learner) (051) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Civil War (United States); Cultural Pluralism; *Ethnic Studies; Grade 11; High Schools; *Immigrants; 'Industrialization; *Interdiiciplinary Approach; Learning Activities; Models; Modern History; *Polish Americans; Reconstruction Era; Revolutionary War (United States); *United States History ABSTRACT Designed to supplement eleventh grade U.S. history textbooks, the self-contained activities in this student guide will help students learn about Polish immigration to America. Intended for use with an accompanyingteacher's guide, the activities are organized '.round five themes:(1) the colonial period: early Polish-American influence;(2) the American Revolution through the Civil War: Polish American perspectives; (3) Reconstruction and immigration;(4) immigration and industrialization; and (5) contemporary issues, concerns, and perspectives. Studenti read, discuss, and answer questions about short reading selections including "Poles in Jamestown," "Influential Poles in Colonial America," "European Factors Influencing Polish Immigration and Settlement in Colonial America," "Tadeusz Kosciuszko (1746-1817)," "Silesian Poles in Texas," "Learning about America and Preparing to Leave Silesia," "Polish Migration and Attitudes in the Post-Revolutionary Period (1783-1860's), "Examples of One Extreme Opinion of a Southern Polish Immigrant," "Reconstruction and Silesian Poles in Panna Maria Texas," "United States Immigration Policy: 1793-1965," "Poletown," "The Polish American Community," and "Current Trends in U.S.