Calculating Ethnicity Through the U.S. Census: the Basque Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Connections Between Sámi and Basque Peoples

Connections between Sámi and Basque Peoples Kent Randell 2012 Siidastallan Outside of Minneapolis, Minneapolis Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota “D----- it Jim, I’m a librarian and an armchair anthropologist??” Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Connections between Sámi and Basque Peoples Hard evidence: - mtDNA - Uniqueness of language Other things may be surprising…. or not. It is fun to imagine other connections, understanding it is not scientific Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Documentary: Suddenly Sámi by Norway’s Ellen-Astri Lundby She receives her mtDNA test, and express surprise when her results state that she is connected to Spain. This also surprised me, and spurned my interest….. Then I ended up living in Boise, Idaho, the city with the largest concentration of Basque outside of Basque Country Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota What is mtDNA genealogy? The DNA of the Mitochondria in your cells. Cell energy, cell growth, cell signaling, etc. mtDNA – At Conception • The Egg cell Mitochondria’s DNA remains the same after conception. • Male does not contribute to the mtDNA • Therefore Mitochondrial mtDNA is the same as one’s mother. Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Four generation mtDNA line Sisters – Mother – Maternal Grandmother – Great-grandmother Jennie Mary Karjalainen b. Kent21 Randell March (c) 2012 1886, --- 2012 Siidastallan,parents from Kuusamo, Finland Linwood Township, Minnesota Isaac Abramson and Jennie Karjalainen wedding picture Isaac is from Northern Norway, Kvaen father and Saami mother from Haetta Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, village. -

American Jewish Yearbook

JEWISH STATISTICS 277 JEWISH STATISTICS The statistics of Jews in the world rest largely upon estimates. In Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, and a few other countries, official figures are obtainable. In the main, however, the num- bers given are based upon estimates repeated and added to by one statistical authority after another. For the statistics given below various authorities have been consulted, among them the " Statesman's Year Book" for 1910, the English " Jewish Year Book " for 5670-71, " The Jewish Ency- clopedia," Jildische Statistik, and the Alliance Israelite Uni- verselle reports. THE UNITED STATES ESTIMATES As the census of the United States has, in accordance with the spirit of American institutions, taken no heed of the religious convictions of American citizens, whether native-born or natural- ized, all statements concerning the number of Jews living in this country are based upon estimates. The Jewish population was estimated— In 1818 by Mordecai M. Noah at 3,000 In 1824 by Solomon Etting at 6,000 In 1826 by Isaac C. Harby at 6,000 In 1840 by the American Almanac at 15,000 In 1848 by M. A. Berk at 50,000 In 1880 by Wm. B. Hackenburg at 230,257 In 1888 by Isaac Markens at 400,000 In 1897 by David Sulzberger at 937,800 In 1905 by "The Jewish Encyclopedia" at 1,508,435 In 1907 by " The American Jewish Year Book " at 1,777,185 In 1910 by " The American Je\rish Year Book" at 2,044,762 DISTRIBUTION The following table by States presents two sets of estimates. -

How Can a Modern History of the Basque Country Make Sense? on Nation, Identity, and Territories in the Making of Spain

HOW CAN A MODERN HISTORY OF THE BASQUE COUNTRY MAKE SENSE? ON NATION, IDENTITY, AND TERRITORIES IN THE MAKING OF SPAIN JOSE M. PORTILLO VALDES Universidad del Pais Vasco Center for Basque Studies, University of Nevada (Reno) One of the more recurrent debates among Basque historians has to do with the very object of their primary concern. Since a Basque political body, real or imagined, has never existed before the end of the nineteenth century -and formally not until 1936- an «essentialist» question has permanently been hanging around the mind of any Basque historian: she might be writing the histo- ry of an non-existent subject. On the other hand, the heaviness of the «national dispute» between Basque and Spanish identities in the Spanish Basque territories has deeply determined the mean- ing of such a cardinal question. Denying the «other's» historicity is a very well known weapon in the hands of any nationalist dis- course and, conversely, claiming to have a millenary past behind one's shoulders, or being the bearer of a single people's history, is a must for any «national» history. Consequently, for those who consider the Spanish one as the true national identity and the Basque one just a secondary «decoration», the history of the Basque Country simply does not exist or it refers to the last six decades. On the other hand, for those Basques who deem the Spanish an imposed identity, Basque history is a sacred territory, the last refuge for the true identity. Although apparently uncontaminated by politics, Basque aca- demic historiography gently reproduces discourses based on na- - 53 - ESPANA CONTEMPORANEA tionalist assumptions. -

Spanish, French, Dutch, Andamerican Patriots of Thb West Indies During

Spanish, French, Dutch, andAmerican Patriots of thb West Indies i# During the AMERICAN Revolution PART7 SPANISH BORDERLAND STUDIES By Granvil~ W. andN. C. Hough -~ ,~~~.'.i~:~ " :~, ~i " .... - ~ ,~ ~"~" ..... "~,~~'~~'-~ ,%v t-5.._. / © Copyright ,i. "; 2001 ~(1 ~,'~': .i: • by '!!|fi:l~: r!;.~:! Granville W. and N. C. Hough 3438 Bahia Blanca West, Apt B ~.l.-c • Laguna Hills, CA 92653-2830 !LI.'.. Email: gwhough(~earthiink.net u~ "~: .. ' ?-' ,, i.. Other books in this series include: • ...~ , Svain's California Patriots in its 1779-1783 War with England - During the.American Revolution, Part 1, 1998. ,. Sp~fin's Califomi0 Patriqts in its 1779-1783 Wor with Englgnd - During the American Revolution, Part 2, :999. Spain's Arizona Patriots in ire |779-1783 War with Engl~n~i - During the Amcricgn RevolutiQn, Third Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Svaln's New Mexico Patriots in its 1779-|783 Wit" wi~ England- During the American Revolution, Fourth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Spain's Texa~ patriot~ in its 1779-1783 War with Enaland - Daring the A~a~ri~n Revolution, Fifth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 2000. Spain's Louisi~a Patriots in its; 1779-1783 War witil England - During.the American Revolution, Sixth StUdy of the Spanish Borderlands, 20(~0. ./ / . Svain's Patriots of Northerrt New Svain - From South of the U. S. Border - in its 1779- 1783 War with Engl~nd_ Eighth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, coming soon. ,:.Z ~JI ,. Published by: SHHAK PRESS ~'~"'. ~ ~i~: :~ .~:,: .. Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research ~.,~.,:" P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655-0490 (714) 894-8161 ~, ~)it.,I ,. -

Stirring the American Melting Pot: Middle Eastern Immigration, the Progressives, and the Legal Construction of Whiteness, 1880-1

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2013 Stirring the American Melting Pot: Middle Eastern Immigration, the Progressives and the Legal Construction of Whiteness, 1880-1924 Richard Soash Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES STIRRING THE AMERICAN MELTING POT: MIDDLE EASTERN IMMIGRATION, THE PROGRESSIVES AND THE LEGAL CONSTRUCTION OF WHITENESS, 1880-1924 By RICHARD SOASH A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2013 Richard Soash defended this thesis on March 7, 2013. The members of the supervisory committee were: Jennifer Koslow Professor Directing Thesis Suzanne Sinke Committee Member Peter Garretson Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To my Grandparents: Evan & Verena Soash Richard & Patricia Fluck iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am extremely thankful for both the academic and financial support that Florida State University has provided for me in the past two years. I would also like to express my gratitude to the FSU History Department for giving me the opportunity to pursue my graduate education here. My academic advisor and committee members – Dr. Koslow, Dr. Sinke, and Dr. Garretson – have been wonderful teachers and mentors during my time in the Master’s Program; I greatly appreciate their patience, humor, and knowledge, both inside and outside of the classroom. -

Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R

Center for BasqueISSN: Studies 1537-2464 Newsletter Center for Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R Center welcomes Gloria Totoricagüena New faculty member Gloria Totoricagüena started to really compare and analyze their FALL began working at the Center last spring, experiences, to look at the similarities and having recently completed her Ph.D. in differences between that Basque Center and 2002 Comparative Politics. Following is an inter- Basque communities in the U.S. So that view with Dr. Totoricagüena by editor Jill really started my academic interest. Al- Berner. though my Master’s degree was in Latin American politics and economic develop- NUMBER 66 JB: How did your interest in the Basque ment, the experience there gave me the idea diaspora originate and develop? GT: I really was born into it, I’ve lived it all my life. My parents are survivors of the In this issue: bombing of Gernika and were refugees to different parts of the Basque Country. And I’ve also lived the whole sheepherder family Gloria Totoricagüena 1 experience that is so common to Basque identity in the U.S. My father came to the Eskerrik asko! 3 U.S. as a sheepherder, and then later went Slavoj Zizek lecture 4 back to Gernika where he met my mother and they married and came here. My parents went Politics after 9/11 5 back and forth actually, and eventually settled Highlights in Boise. So this idea of transnational iden- 6 tity, and multiculturalism, is not new at all to Visiting scholars 7 me. -

The Syrian Community in New Castle and Its Unique Alawi Component, 1900-1940 Anthony B

The Syrian Community in New Castle and Its Unique Alawi Component, 1900-1940 Anthony B. Toth L Introduction and immigration are two important and intertwined phenomena in Pennsylvania's history from 1870 to INDUSTRIALIZATIONWorld War II.The rapid growth of mining, iron and steel pro- duction, manufacturing, and railroads during this period drew millions of immigrants. In turn, the immigrants had a significant effect on their towns and cities. The largest non-English-speaking— groups to jointhe industrial work force — the Italians and Poles have been the sub- jects of considerable scholarly attention. 1 Relatively little, however, has been published about many of the smaller but still significant groups that took part in the "new immigration/' New Castle's Syrian community is one such smaller group. 2 In a general sense, it is typical of other Arabic-speaking immigrant com- munities which settled inAmerican industrial centers around the turn of the century — Lawrence, Fall River, and Springfield, Mass.; Provi- Writer and editor Anthony B. Toth earned his master's degree in Middle East history from Georgetown University. He performed the research for this article while senior writer for the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee Re- search Institute. He has also written articles on the Arab-American communities in Jacksonville, Florida, and Worcester, Massachusetts. —Editor 1 Anyone researching the history of immigrants and Pennsylvania industry cannot escape the enlightening works of John E.Bodnar, who focuses main- ly on the Polish and Italian experiences. In particular, see his Workers' World: Kinship, Community and Protest in an Industrial Society, 1900- 1940 (Baltimore, 1982); Immigration and Industrialization: Ethnicity in an American MillTown, 1870-1940 (Pittsburgh, —1977); and, with Roger Simon and Michael P. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Elko Jaietan 51 Urte Celebrating 51 Years of Basque Tradition Schedule of Events

2014 Elko Jaietan 51 Urte Celebrating 51 Years of Basque Tradition Schedule of Events 2014 Elko Jaietan 51 Urte 2014 Elko Basque Festival Celebrating 51 Years Friday July 4th/Ostirala 4an Uztaila 6:00 p.m. – Kickoff/Txupinazua- Elko Basque Clubhouse Enjoy the evening with your family and friends with a taste of what is to come during the weekend. There will be dancing by the Elko Ariñak dancers, a Paella contest, Basque sport exhibitions of weight lifting and wood chopping, and handball games. Stay for exceptional food, drink, bounce house, and a special performance by this year’s Udaleku group. Saturday July 5th/Larunbata 5an Uztaila 7:00 a.m. – 5K Run/Walk – Eusko Etxtea – Elko Basque Club- house $20 participation fee and you get a t-shirt Registration is at 6:15 a.m. Race starts at 7:00 a.m. For more information contact Cody Krenka at 738-6479 11:00 a.m. – Parade – Downtown Elko 1:00 p.m. - Games & Dancing – Elko County Fairgrounds $10 Adults $5 Children 12 & Under Featuring the following dance groups: Elko Ariñak, Utah’ko Triskalariak, Reno Zazpiak Bat, and Ardi Baltza. Watch traditional Basque rural sports featuring weightlifting, wood chopping, weight carrying, relay, tug o war, and more! 2 9 p.m. Dance - Eusko Etxea - Elko Basque Clubhouse $12 Admission Dance - featuring Boise’s Amuma Says No; come enjoy a fun filled evening of dancing, catching up with old friends and making new ones Sunday July 6th /Igandea 6an Uztaila Eusko Etxea - Elko Basque Clubhouse Please NO outside Food or Beverage 10:30 a.m. -

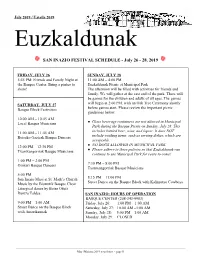

SAN INAZIO FESTIVAL SCHEDULE - July 26 - 28, 2019

1 July 2019 / Uztaila 2019 Euzkaldunak SAN INAZIO FESTIVAL SCHEDULE - July 26 - 28, 2019 FRIDAY, JULY 26 SUNDAY, JULY 28 5:45 PM: Friends and Family Night at 11:00 AM – 4:00 PM the Basque Center. Bring a pintxo to Euzkaldunak Picnic at Municipal Park share! The afternoon will be filled with activities for friends and family. We will gather at the east end of the park. There will be games for the children and adults of all ages. The games SATURDAY, JULY 27 will begin at 2:00 PM, with an Oak Tree Ceremony shortly Basque Block Festivities before games start. Please review the important picnic guidelines below: 10:00 AM – 10:45 AM ● Local Basque Musicians Glass beverage containers are not allowed in Municipal Park during the Basque Picnic on Sunday, July 28. This 11:00 AM – 11:45 AM includes bottled beer, wine, and liquor. It does NOT Boiseko Gazteak Basque Dancers include cooking items, such as serving dishes, which are acceptable. ● 12:00 PM – 12:30 PM NO DOGS ALLOWED IN MUNICIPAL PARK ● Txantxangorriak Basque Musicians Please adhere to these policies so that Euzkaldunak can continue to use Municipal Park for years to come! 1:00 PM – 2:00 PM Oinkari Basque Dancers 7:30 PM – 8:00 PM Txantxangorriak Basque Musicians 5:00 PM San Inazio Mass at St. Mark’s Church 8:15 PM – 11:00 PM Music by the Biotzetik Basque Choir Street Dance on the Basque Block with Kalimotxo Cowboys Liturgical dance by Boise Oñati Dantza Taldea SAN INAZIO: HOURS OF OPERATION BASQUE CENTER (208-343-9983) 9:00 PM – 1:00 AM Friday, July 26: 1:00 PM – 1:00 AM Street Dance on the Basque Block Saturday, July 27: 10:00 AM –1:00 AM with Amerikanuak Sunday, July 28: 5:00 PM – 1:00 AM Monday, July 29: CLOSED May /Maiatza 2019 newsletter - page 1 2 FRIENDS AND FAMILY NIGHT – JULY 26 Please join us as we kick off another great San Inazio Basque Festival Friday, July 26, at 5:45 PM. -

A Place-Based Approach to the Long Anthropocene

sustainability Article Contingency and Agency in the Mountain Landscapes of the Western Pyrenees: A Place-Based Approach to the Long Anthropocene Ted L Gragson 1,2,*, Michael R. Coughlan 3 and David S. Leigh 4 1 Department of Anthropology, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA 2 Laboratoire TRACES-UMR 5608, Université Toulouse-Jean Jaurès, 31000 Toulouse, France 3 Institute for a Sustainable Environment, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Geography, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 14 April 2020; Accepted: 4 May 2020; Published: 9 May 2020 Abstract: Regional- and biome-scale paleoecological analyses and archaeological syntheses in the mountain landscapes of the western Pyrenees suggest that the Long Anthropocene began with agropastoral land use at the onset of the Neolithic. Historical and geographic analyses emphasize the marginality of the western Pyrenees and the role of enforced social norms exacted by intense solidarities of kin and neighbors in agropastoral production. Both are satisfying and simple narratives, yet neither offers a realistic framework for understanding complex processes or the contingency and behavioral variability of human agents in transforming a landscape. The Long Anthropocene in the western Pyrenees was a spatially and temporally heterogeneous and asynchronous process, and the evidence frequently departs from conventional narratives about human landscape degradation in this agropastoral situation. A complementary place-based strategy that draws on geoarchaeological, biophysical, and socio-ecological factors is used to examine human causality and environmental resilience and demonstrate their relationship with the sustainability of mountain landscapes of the western Pyrenees over medium to long time intervals. -

Ruling America's Colonies: the Insular Cases Juan R

YALE LAW & POLICY REVIEW Ruling America's Colonies: The Insular Cases Juan R. Torruella* INTRODUCTION .................................................................. 58 I. THE HISTORICAL BACKDROP TO THE INSULAR CASES..................................-59 11. THE INSULAR CASES ARE DECIDED ......................................... 65 III. LIFE AFTER THE INSULAR CASES.......................... .................. 74 A. Colonialism 1o ......................................................... 74 B. The Grinding Stone Keeps Grinding........... ....... ......................... 74 C. The Jones Act of 1917, U.S. Citizenship, and President Taft ................. 75 D. The Jones Act of 1917, U.S. Citizenship, and ChiefJustice Taft ............ 77 E. Local Self-Government v. Colonial Status...........................79 IV. WHY THE UNITED STATES-PUERTO Rico RELATIONSHIP IS COLONIAL...... 81 A. The PoliticalManifestations of Puerto Rico's Colonial Relationship.......82 B. The Economic Manifestationsof Puerto Rico's ColonialRelationship.....82 C. The Cultural Manifestationsof Puerto Rico's Colonial Relationship.......89 V. THE COLONIAL STATUS OF PUERTO Rico Is UNAUTHORIZED BY THE CONSTITUTION AND CONTRAVENES THE LAW OF THE LAND AS MANIFESTED IN BINDING TREATIES ENTERED INTO BY THE UNITED STATES ............................................................. 92 CONCLUSION .................................................................... 94 * Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. The substance of this Article was presented in