A Guide to Researching Your Neighborhood History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Journal of the Central Plains Volume 37, Number 3 | Autumn 2014

Kansas History A Journal of the Central Plains Volume 37, Number 3 | Autumn 2014 A collaboration of the Kansas Historical Foundation and the Department of History at Kansas State University A Show of Patriotism German American Farmers, Marion County, June 9, 1918. When the United States formally declared war against Onaga. There are enough patriotic citizens of the neighborhood Germany on April 6, 1917, many Americans believed that the to enforce the order and they promise to do it." Wamego mayor war involved both the battlefield in Europe and a fight against Floyd Funnell declared, "We can't hope to change the heart of disloyal German Americans at home. Zealous patriots who the Hun but we can and will change his actions and his words." considered German Americans to be enemy sympathizers, Like-minded Kansans circulated petitions to protest schools that spies, or slackers demanded proof that immigrants were “100 offered German language classes and churches that delivered percent American.” Across the country, but especially in the sermons in German, while less peaceful protestors threatened Midwest, where many German settlers had formed close- accused enemy aliens with mob violence. In 1918 in Marion knit communities, the public pressured schools, colleges, and County, home to a thriving Mennonite community, this group churches to discontinue the use of the German language. Local of German American farmers posed before their tractor and newspapers published the names of "disloyalists" and listed threshing machinery with a large American flag in an attempt their offenses: speaking German, neglecting to donate to the to prove their patriotism with a public display of loyalty. -

HURRICANE HARVEY RELIEF EFFORTS Supporting Immigrant Communities

HURRICANE HARVEY RELIEF EFFORTS Supporting Immigrant Communities Guide to Disaster Assistance Services for Immigrant Houstonians Mayor’s Office of New Americans & Immigrant Communities Mayor’s Office of Public Safety Office of Emergency Management A Message from the City of Houston Mayor’s Office of New Americans and Immigrant Communities To All Houstonians and Community Partners, In the aftermath of a natural disaster of unprecedented proportions, the people of Houston have inspired the nation with their determination, selflessness, and camaraderie. Hurricane Harvey has affected us all deeply, and the road to recovery will surely be a long one. We can find hope, however, in the ways in which Houstonians of all ethnic, racial, national, religious, and socioeconomic backgrounds have come together to help one another. This unity in diversity is one of the things that makes Houston such a special city. Our office is here to offer special support to the thriving immigrant community that forms such an integral part of this city and to help immigrants to address the unique challenges they face in the wake of this natural disaster. For our community partners, we recognize the critical role you play in the process of helping Houstonians recover from the devastating effects of Hurricane Harvey. Non- profit and community-based organizations are on the front lines of service delivery across Houston, and we want to ensure that you have the information and resources you need to help your communities recover. This guide—which will soon be available as an app—provides detailed information about the types of federal, state, and local disaster-assistance services available and where you can go to access those services. -

Harris County Public Library Records CR57 (1920 – 2014, Bulk: 1920 - 2000)

Harris County Archives Houston, Texas Finding Aid Harris County Public Library Records CR57 (1920 – 2014, Bulk: 1920 - 2000) Size: 31 cubic feet, 16 items Accession Numbers: 2007.005, Restrictions on Access: None 2009.003, 2015.016, 2016.003, Restrictions on Use: None 2016.004, 2017.001, 2017.003 Acquisition: Harris County Public Processed by: AnnElise Golden 2008; Library, 2007, 2009, 2015, 2016, 2017. Sarah Canby Jackson, 2015, 2021; Terrin Rivera 2019 – 2021. Citation: [Identification of Item], Harris County Public Library Records, Harris County Archives, Houston, Texas. Agency History: In the fall of 1920 a campaign for library services began for rural Harris County. Under the direction of attorney Arthur B. Dawes with assistance from the Dairy Men’s Association, Julia Ideson, Librarian of the Houston Public Library, I.H. Mowery of Aldine, Miss Christine Baker of Barker, County Judge Chester H. Bryan, Edward F. Pickering, and Rev. Harris Masterson, a citizen’s committee circulated petitions for a county library throughout Harris County. Dawes presented the plans and petitions signed by Harris County qualified voters to the Commissioners Court and, with skepticism, the Commissioners Court ordered a budget of $6500.00 for the county library for a trial period of one year. If the library did not succeed, the Commissioners Court would not approve a budget for a second year. The Harris County Commissioners Court appointed its first librarian, Lucy Fuller, in May 1921, and with an office on the fifth floor of the Harris County Court House, the Harris County Public Library was in operation. At the close of the year, the HCPL had twenty- six library branches and book wagon stations in operation, 3,455 volumes in the library, and 19,574 volumes in circulation. -

The Heights a Historic Houston Neighborhood

Homing in on Residents and developers vie for the heart of the Heights a historic Houston neighborhood. BY ANNE SLO A N N THE EARLY 21ST CENTURY , people are often sur- Cooley), somehow saw potential for tremendous growth prised to find a large historic subdivision nestled in the countryside that surrounds the town. The land com- in a tree-shaded area just over two miles from the pany, and Carter as an individual, jointly and wisely pur- chrome-and-glass skyscrapers of downtown Hous- chased 1,796 acres situated a few miles away and 23 feet ton. After all, Houston has a reputation (especially, above the “utter flatness” of little Houston, naming the perhaps, among those who have never been here) new venture Houston Heights. ias a city dominated by freeways and sprawl. A native of Massachusetts, Carter designed Heights In 1891, though, Houston was a small, swampy town, Blvd., a replica of Boston’s Commonwealth Blvd., to be surrounded by countryside that was, then as now, prone to the grand entry to the new development. Heights Blvd. is flooding when the flat landscape of southeast Texas a divided street 150 feet wide, with a 60-foot-wide espla- allows the ample rainfall each year to quickly swell bay- nade down the middle, that spans White Oak Bayou over ous and creeks. Oscar Martin Carter, a self-made million- twin bridges. The first homes, imposing Victorian struc- aire and president of the Omaha & South Texas Land tures, were built along the boulevard for investors, but Company, and D.D. Cooley, a company official (and Houston Heights was not planned for the elite. -

Hispanic Archival Collections Houston Metropolitan Research Cent

Hispanic Archival Collections People Please note that not all of our Finding Aids are available online. If you would like to know about an inventory for a specific collection please call or visit the Texas Room of the Julia Ideson Building. In addition, many of our collections have a related oral history from the donor or subject of the collection. Many of these are available online via our Houston Area Digital Archive website. MSS 009 Hector Garcia Collection Hector Garcia was executive director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations, Diocese of Galveston-Houston, and an officer of Harris County PASO. The Harris County chapter of the Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations (PASO) was formed in October 1961. Its purpose was to advocate on behalf of Mexican Americans. Its political activities included letter-writing campaigns, poll tax drives, bumper sticker brigades, telephone banks, and community get-out-the- vote rallies. PASO endorsed candidates supportive of Mexican American concerns. It took up issues of concern to Mexican Americans. It also advocated on behalf of Mexican Americans seeking jobs, and for Mexican American owned businesses. PASO produced such Mexican American political leaders as Leonel Castillo and Ben. T. Reyes. Hector Garcia was a member of PASO and its executive secretary of the Office of Community Relations. In the late 1970's, he was Executive Director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations for the Diocese of Galveston-Houston. The collection contains some materials related to some of his other interests outside of PASO including reports, correspondence, clippings about discrimination and the advancement of Mexican American; correspondence and notices of meetings and activities of PASO (Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations of Harris County. -

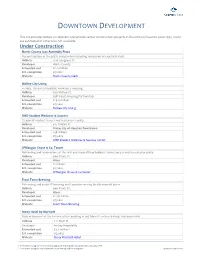

Downtown Development Project List

DOWNTOWN DEVELOPMENT This list provides details on all public and private sector construction projects in Downtown Houston since 1995. Costs are estimated or otherwise not available. Under Construction Harris County Jury Assembly Plaza Reconstruction of the plaza and pavilion including relocation of electrical vault. Address 1210 Congress St. Developer Harris County Estimated cost $11.3 million Est. completion 3Q 2021 Website Harris County Clerk McKee City Living 4‐story, 120‐unit affordable‐workforce housing. Address 626 McKee St. Developer Gulf Coast Housing Partnership Estimated cost $29.9 million Est. completion 4Q 2021 Website McKee City Living UHD Student Wellness & Success 72,000 SF student fitness and recreation facility. Address 315 N Main St. Developer University of Houston Downtown Estimated cost $38 million Est. completion 2Q 2022 Website UHD Student Wellness & Success Center JPMorgan Chase & Co. Tower Reframing and renovations of the first and second floor lobbies, tunnel access and the exterior plaza. Address 600 Travis St. Developer Hines Estimated cost $2 million Est. completion 3Q 2021 Website JPMorgan Chase & Co Tower Frost Town Brewing Reframing and 9,100 SF brewing and taproom serving locally inspired beers Address 600 Travis St. Developer Hines Estimated cost $2.58 million Est. completion 3Q 2021 Website Frost Town Brewing Moxy Hotel by Marriott Redevelopment of the historic office building at 412 Main St. into a 13‐story, 119‐room hotel. Address 412 Main St. Developer InnJoy Hospitality Estimated cost $4.4 million P Est. completion 2Q 2022 Website Moxy Marriott Hotel V = Estimated using the Harris County Appriasal Distict public valuation data, January 2019 P = Estimated using the City of Houston's permitting and licensing data Updated 07/01/2021 Harris County Criminal Justice Center Improvement and flood damage mitigation of the basement and first floor. -

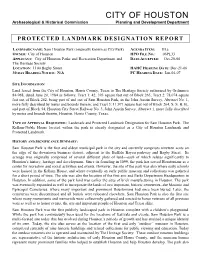

Protected Landmark Designation Report

CITY OF HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission Planning and Development Department PROTECTED LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT LANDMARK NAME: Sam Houston Park (originally known as City Park) AGENDA ITEM: III.a OWNER: City of Houston HPO FILE NO.: 06PL33 APPLICANT: City of Houston Parks and Recreation Department and DATE ACCEPTED: Oct-20-06 The Heritage Society LOCATION: 1100 Bagby Street HAHC HEARING DATE: Dec-21-06 30-DAY HEARING NOTICE: N/A PC HEARING DATE: Jan-04-07 SITE INFORMATION: Land leased from the City of Houston, Harris County, Texas to The Heritage Society authorized by Ordinance 84-968, dated June 20, 1984 as follows: Tract 1: 42, 393 square feet out of Block 265; Tract 2: 78,074 square feet out of Block 262, being part of and out of Sam Houston Park, in the John Austin Survey, Abstract No. 1, more fully described by metes and bounds therein; and Tract 3: 11,971 square feet out of Block 264, S. S. B. B., and part of Block 54, Houston City Street Railway No. 3, John Austin Survey, Abstract 1, more fully described by metes and bounds therein, Houston, Harris County, Texas. TYPE OF APPROVAL REQUESTED: Landmark and Protected Landmark Designation for Sam Houston Park. The Kellum-Noble House located within the park is already designated as a City of Houston Landmark and Protected Landmark. HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE SUMMARY: Sam Houston Park is the first and oldest municipal park in the city and currently comprises nineteen acres on the edge of the downtown business district, adjacent to the Buffalo Bayou parkway and Bagby Street. -

Federal Depository Library Directory

Federal Depositoiy Library Directory MARCH 2001 Library Programs Service Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office Wasliington, DC 20401 U.S. Government Printing Office Michael F. DIMarlo, Public Printer Superintendent of Documents Francis ]. Buclcley, Jr. Library Programs Service ^ Gil Baldwin, Director Depository Services Robin Haun-Mohamed, Chief Federal depository Library Directory Library Programs Service Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office Wasliington, DC 20401 2001 \ CONTENTS Preface iv Federal Depository Libraries by State and City 1 Maps: Federal Depository Library System 74 Regional Federal Depository Libraries 74 Regional Depositories by State and City 75 U.S. Government Printing Office Booi<stores 80 iii Keeping America Informed Federal Depository Library Program A Program of the Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO) *******^******* • Federal Depository Library Program (FDLP) makes information produced by Federal Government agencies available for public access at no fee. • Access is through nearly 1,320 depository libraries located throughout the U.S. and its possessions, or, for online electronic Federal information, through GPO Access on the Litemet. * ************** Government Information at a Library Near You: The Federal Depository Library Program ^ ^ The Federal Depository Library Program (FDLP) was established by Congress to ensure that the American public has access to its Government's information (44 U.S.C. §§1901-1916). For more than 140 years, depository libraries have supported the public's right to know by collecting, organizing, preserving, and assisting users with information from the Federal Government. The Government Printing Office provides Government information products at no cost to designated depository libraries throughout the country. These depository libraries, in turn, provide local, no-fee access in an impartial environment with professional assistance. -

The Heights | Houston Asana Partners

ASANA PARTNERS THE HEIGHTS | HOUSTON We encourage you to soar to new heights by exploring this famous Houston neighborhood. Known for its history dating back to the late 1800s, The Heights has become one of Houston’s most talked-about areas to live. The neighborhood comes to life with its recognizable architecture and undeniable character. The streets are lined with a stimulating mix of mom-and-pop shops, hip restaurants, and whimsical boutiques. Strolling through the streets of The Heights can only be described as picturesque. The Heights is a historic neighborhood, with a modern appetite, but residents and visitors can expect to find something to suit every taste. 2 HOUSTON HEIGHTS | HOUSTON NORTHSIDE 290 69 610 Historic Heights East 20th St 2200 Yale St Lowell St Market 250 w 19th St Heights Marketplace 1.5 MI GREATER NEAR 3 MI HEIGHTS NORTHSIDE 5 MI 610 Heights Mercantile HERMAN 10 BROWN PARK GREATER FIFTH WARD 10 HUNTERS CREEK VILLAGE MEMORIAL PARK DWNOWN HSN SECOND WARD MIDTOWN GREATER GREATER EAST END UPTOWN THIRD WARD 69 UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON HOUSTON ZOO 288 45 90 SOUTH UNION 610 3 HOUSTON HEIGHTS | HOUSTON Demographics 1 MI RADIUS Population (2018) – 22,360 Households – 10,994 Avg. HH Income – $120,082 Median Age – 37 Daytime Demo – 18,620 Education (Bach+) – 70% 3 MI RADIUS Population (2018) – 191,721 Households – 86,529 Avg. HH Income – $120,136 Median Age – 37 Daytime Demo – 321,648 Education (Bach+) – 58% 5 MI RADIUS Population (2018) – 459,385 Households – 201,233 Avg. HH Income –$112,144 Median Age – 36 Daytime Demo –753,938 -

Houston Heights / Restaurant Space for Lease

4705 INKER ST. HOUSTON, TX 77007 HOUSTON HEIGHTS / RESTAURANT SPACE FOR LEASE FOR LEASING INFORMATION: 3217 Montrose, Suite 200 ZACH WOLF, Director of Leasing Houston, Texas 77006 [email protected] www.braunenterprises.com 713.541.0066, x24 THE WOODLANDS T H E G R A N D P A R K W A Y PROPERTY 249 OVERVIEW NORTH 4545 5959 BELT LOCATION 90 4705 Inker Street Houston, Texas 77007 290 NORTHWEST SPACE AVAILABLE 8 Total Size: 4,700 SF 1st Floor: 2,700 SF 8 2nd Floor: 2,000 SF THE HEIGHTS ENERGY CORRIDOR 610610 PARKING 1010 18 parking spaces available; MEMORIAL street parking available 1010 DOWNTOWN GALLERIA / UPTOWN WESTCHASE 5959 TRAFFIC COUNTS MONTROSE / MIDTOWN Daily average on Shepherd Drive: 225 25,824 VPD Daily average on Interstate 10: 168,815 VPD 2016 DEMOGRAPHIC SNAPSHOT ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 90 Prime space on the north pocket of Shepherd Drive and Inker St. 1 mile 15,749 1 mile 98,006 8 1 mile $97,261 Surrounding neighborhood provides vibrant community comprised of up- 3 mile 189,463 3 mile 305,458 3 mile $102,491 and-coming restaurants, shopping SUGAR LAND 5 mile 423,750 Daytime 5 mile 656,081 areas and outdoor walking trails. Population Population Avg. HH 5 mile $97,854 Income 288 4545 FOR LEASING INFORMATION: 3217 Montrose, Suite 200 ZACH WOLF, Director of Leasing Houston, Texas 77006 [email protected] www.braunenterprises.com 713.541.0066, x24 The Grand Parkway COMPLETED IN PROGRESS 610610 45 W.W. 20TH20TH ST.ST. 45 SURROUNDING NEAR NORTSIE NEIGHBORHOODS LAROO TIMERGROE 610610 GREATER EIGTS 1010 WASHINGTONWASHINGTON AVE.AVE. -

30Th Anniversary of the Center for Public History

VOLUME 12 • NUMBER 2 • SPRING 2015 HISTORY MATTERS 30th Anniversary of the Center for Public History Teaching and Collection Training and Research Preservation and Study Dissemination and Promotion CPH Collaboration and Partnerships Innovation Outreach Published by Welcome Wilson Houston History Collaborative LETTER FROM THE EDITOR 28½ Years Marty Melosi was the Lone for excellence in the fields of African American history and Ranger of public history in our energy/environmental history—and to have generated new region. Thirty years ago he came knowledge about these issues as they affected the Houston to the University of Houston to region, broadly defined. establish and build the Center Around the turn of the century, the Houston Public for Public History (CPH). I have Library announced that it would stop publishing the been his Tonto for 28 ½ of those Houston Review of History and Culture after twenty years. years. Together with many others, CPH decided to take on this journal rather than see it die. we have built a sturdy outpost of We created the Houston History Project (HHP) to house history in a region long neglectful the magazine (now Houston History), the UH-Oral History of its past. of Houston, and the Houston History Archives. The HHP “Public history” includes his- became the dam used to manage the torrent of regional his- Joseph A. Pratt torical research and training for tory pouring out of CPH. careers outside of writing and teaching academic history. Establishing the HHP has been challenging work. We In practice, I have defined it as historical projects that look changed the format, focus, and tone of the magazine to interesting and fun. -

Houston Chronicle Index to Mexican American Articles, 1901-1979

AN INDEX OF ITEMS RELATING TO MEXICAN AMERICANS IN HOUSTON AS EXTRACTED FROM THE HOUSTON CHRONICLE This index of the Houston Chronicle was compiled in the Spring and summer semesters of 1986. During that period, the senior author, then a Visiting Scholar in the Mexican American Studies Center at the University of Houston, University Park, was engaged in researching the history of Mexican Americans in Houston, 1900-1980s. Though the research tool includes items extracted for just about every year between 1901 (when the Chronicle was established) and 1970 (the last year searched), its major focus is every fifth year of the Chronicle (1905, 1910, 1915, 1920, and so on). The size of the newspaper's collection (more that 1,600 reels of microfilm) and time restrictions dictated this sampling approach. Notes are incorporated into the text informing readers of specific time period not searched. For the era after 1975, use was made of the Annual Index to the Houston Post in order to find items pertinent to Mexican Americans in Houston. AN INDEX OF ITEMS RELATING TO MEXICAN AMERICANS IN HOUSTON AS EXTRACTED FROM THE HOUSTON CHRONICLE by Arnoldo De Leon and Roberto R. Trevino INDEX THE HOUSTON CHRONICLE October 22, 1901, p. 2-5 Criminal Docket: Father Hennessey this morning paid a visit to Gregorio Cortez, the Karnes County murderer, to hear confession November 4, 1901, p. 2-3 San Antonio, November 4: Miss A. De Zavala is to release a statement maintaining that two children escaped the Alamo defeat. History holds that only a woman and her child survived the Alamo battle November 4, 1901, p.