The Heights a Historic Houston Neighborhood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Heights | Houston Asana Partners

ASANA PARTNERS THE HEIGHTS | HOUSTON We encourage you to soar to new heights by exploring this famous Houston neighborhood. Known for its history dating back to the late 1800s, The Heights has become one of Houston’s most talked-about areas to live. The neighborhood comes to life with its recognizable architecture and undeniable character. The streets are lined with a stimulating mix of mom-and-pop shops, hip restaurants, and whimsical boutiques. Strolling through the streets of The Heights can only be described as picturesque. The Heights is a historic neighborhood, with a modern appetite, but residents and visitors can expect to find something to suit every taste. 2 HOUSTON HEIGHTS | HOUSTON NORTHSIDE 290 69 610 Historic Heights East 20th St 2200 Yale St Lowell St Market 250 w 19th St Heights Marketplace 1.5 MI GREATER NEAR 3 MI HEIGHTS NORTHSIDE 5 MI 610 Heights Mercantile HERMAN 10 BROWN PARK GREATER FIFTH WARD 10 HUNTERS CREEK VILLAGE MEMORIAL PARK DWNOWN HSN SECOND WARD MIDTOWN GREATER GREATER EAST END UPTOWN THIRD WARD 69 UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON HOUSTON ZOO 288 45 90 SOUTH UNION 610 3 HOUSTON HEIGHTS | HOUSTON Demographics 1 MI RADIUS Population (2018) – 22,360 Households – 10,994 Avg. HH Income – $120,082 Median Age – 37 Daytime Demo – 18,620 Education (Bach+) – 70% 3 MI RADIUS Population (2018) – 191,721 Households – 86,529 Avg. HH Income – $120,136 Median Age – 37 Daytime Demo – 321,648 Education (Bach+) – 58% 5 MI RADIUS Population (2018) – 459,385 Households – 201,233 Avg. HH Income –$112,144 Median Age – 36 Daytime Demo –753,938 -

Houston Heights / Restaurant Space for Lease

4705 INKER ST. HOUSTON, TX 77007 HOUSTON HEIGHTS / RESTAURANT SPACE FOR LEASE FOR LEASING INFORMATION: 3217 Montrose, Suite 200 ZACH WOLF, Director of Leasing Houston, Texas 77006 [email protected] www.braunenterprises.com 713.541.0066, x24 THE WOODLANDS T H E G R A N D P A R K W A Y PROPERTY 249 OVERVIEW NORTH 4545 5959 BELT LOCATION 90 4705 Inker Street Houston, Texas 77007 290 NORTHWEST SPACE AVAILABLE 8 Total Size: 4,700 SF 1st Floor: 2,700 SF 8 2nd Floor: 2,000 SF THE HEIGHTS ENERGY CORRIDOR 610610 PARKING 1010 18 parking spaces available; MEMORIAL street parking available 1010 DOWNTOWN GALLERIA / UPTOWN WESTCHASE 5959 TRAFFIC COUNTS MONTROSE / MIDTOWN Daily average on Shepherd Drive: 225 25,824 VPD Daily average on Interstate 10: 168,815 VPD 2016 DEMOGRAPHIC SNAPSHOT ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 90 Prime space on the north pocket of Shepherd Drive and Inker St. 1 mile 15,749 1 mile 98,006 8 1 mile $97,261 Surrounding neighborhood provides vibrant community comprised of up- 3 mile 189,463 3 mile 305,458 3 mile $102,491 and-coming restaurants, shopping SUGAR LAND 5 mile 423,750 Daytime 5 mile 656,081 areas and outdoor walking trails. Population Population Avg. HH 5 mile $97,854 Income 288 4545 FOR LEASING INFORMATION: 3217 Montrose, Suite 200 ZACH WOLF, Director of Leasing Houston, Texas 77006 [email protected] www.braunenterprises.com 713.541.0066, x24 The Grand Parkway COMPLETED IN PROGRESS 610610 45 W.W. 20TH20TH ST.ST. 45 SURROUNDING NEAR NORTSIE NEIGHBORHOODS LAROO TIMERGROE 610610 GREATER EIGTS 1010 WASHINGTONWASHINGTON AVE.AVE. -

Houston Heights / Future Development Site

2401 N. SHEPHERD DR. HOUSTON, TX 77008 HOUSTON HEIGHTS / FUTURE DEVELOPMENT SITE FOR LEASING INFORMATION: 3217 Montrose, Suite 200 ZACH WOLF, Director of Leasing Houston, Texas 77006 [email protected] www.braunenterprises.com 713.541.0066, x24 THE WOODLANDS T H E G R A N D P A R K W A Y PROPERTY 249 OVERVIEW NORTH 4545 5959 BELT LOCATION 90 2401 N. Shepherd Drive Houston, Texas 77008 290 8 NORTHWEST SPACE AVAILABLE Total Size: 24,307 SF Building 1, 1st Floor: 4,396 SF 6,562 SF Building 1, 2nd Floor: 8 Building 2, 1st Floor: 10,349 SF THE HEIGHTS ENERGY CORRIDOR 610610 PARKING 10 161 spaces available 10 MEMORIAL 1010 DOWNTOWN GALLERIA / UPTOWN TRAFFIC COUNTS WESTCHASE 5959 Daily average on N. Shepherd Dr.: MONTROSE / 40,710 VPD MIDTOWN 225 Daily average on 24th St.: 940 VPD ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 2015 DEMOGRAPHIC SNAPSHOT Prime space on the northwest corner 90 of 24th Street and N. Shepherd Drive; adjacent to a brand new Heights H-E-B. 1 mile 9,459 1 mile 19,951 8 1 mile $110,383 Surrounding neighborhood provides vibrant community comprised of up- 3 mile 70,010 3 mile 161,717 3 mile $99,302 and-coming restaurants, shopping SUGAR LAND 5 mile 177,960 Daytime 5 mile 420,477 areas and outdoor walking trails. Population Population Avg. HH 5 mile $94,821 Income 288 4545 FOR LEASING INFORMATION: 3217 Montrose, Suite 200 ZACH WOLF, Director of Leasing Houston, Texas 77006 [email protected] www.braunenterprises.com 713.541.0066, x24 The Grand Parkway COMPLETED IN PROGRESS SURROUNDING NEIGHBORHOODS OA FOREST GAREN OAS NORTLINE W.W. -

Spring Branch Management District Comprehensive Plan 2015 - 2030

REIMAGINE SPRING BRANCH SPRING BRANCH MANAGEMENT DISTRICT COMPREHENSIVE PLAN 2015 - 2030 AUGUST 2015 SPRING BRANCH MANAGEMENT DISTRICT COMPREHENSIVE PLANNING COMMITTEE BOARD OF DIRECTORS 2015 C. David Schwab Position 1: C. David Schwab Thomas Sumner Position 2: Thomas Sumner Victor Alvarez Position 3: Catherine Barchfeld-Alexander Dan Silvestri Position 4: Sherri Oldham Patricia Maddox Position 5: Victor Alvarez Jason Johnson Position 6: Mauricio Valdes Rino Cassinelli Position 7: Dan Silvestri John Chiang Position 8: Patricia Maddox Position 9: David Gutierrez SPRING BRANCH MANAGEMENT DISTRICT STAFF Position 10: Jason Johnson David Hawes Position 11: Rino Cassinelli Josh Hawes Position 12: Vacant Kristen Gonzales Position 13: John Chiang Gretchen Larson Alice Lee SPRING BRANCH MANAGEMENT DISTRICT PLANNING CONSULTANTS SWA Group DHK Development Traffic Engineers, Inc. 2 CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction 9 1.1 District Vision + Purpose 11 1.2 Comprehensive Plan Components 12 1.3 How to Use this Comprehensive Plan 13 2.0 Infrastructure 15 2.0 Introduction + Methodology 16 2.1 Existing Conditions 20 2.1.1 Roadway Quality 20 2.1.2 Public Utilities 22 2.1.3 Drainage 28 2.2 Known Proposed Interventions 31 2.2.1 ReBuild Houston 31 2.2.2 Capital Improvements 32 2.3 Future Unknown and Recommendations 33 2.4 Strategies for the Future 35 2.4.1 Advocate for Projects 35 2.4.2 Engage with Development 37 2.4.3 Drainage Partnerships 38 2.4.4 LID/Green Infrastructure 39 Spring Branch Management District Comprehensive Plan 2015-2030 3 3.0 Land Use 41 3.0 Introduction -

National Register of Historic Places REGISTRATION FORM NPS Form 10-900 OMB No

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National RegisterSBR of Historic Places Registration Draft Form 1. Name of Property Historic Name: Houses at 1217 and 1219 Tulane Street Other name/site number: NA Name of related multiple property listing: Historic Resources of Houston Heights MRA 2. Location Street & number: 1217 Tulane Street City or town: Houston State: Texas County: Harris Not for publication: Vicinity: 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this ( nomination request for determination of eligibility) meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ( meets does not meet) the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following levels of significance: national statewide local Applicable National Register Criteria: A B C D State Historic Preservation Officer ___________________________ Signature of certifying official / Title Date Texas Historical Commission State or Federal agency / bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. _______________________________________________________________________ __________________________ Signature of commenting or other official Date ____________________________________________________________ -

Heights Fun Run — June 3

Newsletter of the Houston Heights Association Volume 43, Number Six, June 2017 ® Heights Fun Run — June 3 MONTHLY MEETING It’s almost time to kick off summer on the right foot by taking & HAPPY HOUR your place in the Houston Heights Association’s 32nd Annual Heights Fun Run on Saturday, June 3, 2017. Meet new neighbors and This annual family-friendly event begins and ends in Marmion friends on the second Monday Park in the 1800 block of Heights Boulevard, and includes a 5K Run, of the month at the Houston a 5K Walk and a Kids 1K race and — NEW this year — a 10K race! Heights Fire Station, 12th at Yale. The USA Track & Field The socializing starts at 6:30 PM; certified course along scenic the meeting begins at 7:00 PM. Heights Boulevard will provide June 12: “Meet our Heights a run with a view. Individual 5K Super Heroes - Safety and and 10K runners’ timing will be Security” tracked with disposable timing The Houston Heights chips and conducted by Run Association is pleased to host an Wild Sports Timing. The Kids evening with our crime fighting 1K race will not be timed, nor professionals. Learn about will walkers. crime statistics, tips to be safe, The 5K Run will start at 7:30 AM, the 5K Walk at 7:35 AM, the and membership in the HHA’s 10K Run at 7:40 AM, and the Kids 1K at 8:30 AM. Constable Patrol Program. After 8:00 AM, everyone is invited to the After-Race Party in the Officers from the Precinct 1 Park (always a good time!) which will include entertainment, door Constable’s Office, Houston prizes, refreshments, and more. -

City of Houston Assisted Properties Senior Housing 2100 Memorial Drive Apts. 2100 Memorial Dr., Houston, TX 77007 Senior 19

City of Houston Assisted Properties Senior Housing 2100 Memorial Drive 2100 Memorial Dr., Senior 19 101 https://www.2100memorialhouston.com/ Apts. Houston, TX 77007 7 Allen Parkway Village 1600 Allen Pkwy, Senior 50 255 http://www.historicoaks.com/ ((APV),(HOAPV) Senior Houston, TX 77019 0 Village Chelsea Senior 3230 W. Little York Rd., Senior 15 16 https://www.chelseaseniorcommunity.com/ Community Houston, TX 77088 0 Commons of Grace 9110 Tidwell Rd., Senior 10 31 https://www.commonsofgrace.com/ Senior Houston TX,77078 8 Corinthian Village 6105 W. Orem Dr., Senior 12 40 http://www.corinthianvillagehouston.com/ Houston, TX 77085 4 Floral Garden Apts. 7950 1/2 S. Sam Houston Senior 10 6 http://floralgardenapts.com/ W. Pkwy, Houston, TX 0 77085 Goldberg Towers (B'nai 10909 Fondren Rd., Senior 30 300 http://www.gbbt.org/ B'rith Senior Citizens) Houston, TX 77096 0 Golden Bamboo Village 12010 Dashwood Dr., Senior 60 44 Houston TX, 77072 Golden Bamboo Village 6628 Synott, Houston TX, Senior 13 10 https://www.goldenbamboovillage3.com/ III 77083 0 Hometowne on Bellfort 10888 Huntington Senior 21 16 https://www.hometownebellfort.com/ Estates, Houston, TX 0 77099 Hometowne on Wayside 7447 N Wayside Dr., Senior 12 27 https://www.hometownewayside.com/ Houston, TX 77028 8 Houston Heights Tower 330 W. 19th St., Houston Senior 22 168 TX, 77006 3 Independence Hall Apts. 6 Burress St., Houston, TX Senior 29 149 77007 2 Kingwood Senior Villages 435 Northpines Dr., Senior 19 22 https://kingwoodseniorvillage.com/ Kingwood TX 77339 3 Langwick Senior 955 Langwick Dr., Senior 12 10 http://www.langwickseniorresidences.com/ Residences Houston, TX 77060 8 Mariposa at Reed Rd 2889 Reed Rd., Houston, Senior 18 44 http://www.mariposaapartmenthomes.com/ Senior Apts. -

1949 Indiana St. Houston, Tx. Montrose

1949 Indiana St. Houston, Tx. Montrose 1949 Indiana St. is in the Park Civic / Vermont Commons neighborhood association (they used to be two separate ones, but are essentially merged). It is an active civic association, and dues (which are optional) go towards a dedicated constable for the area, which means there is greater police presence in the neighborhood, and a dedicated number to call if anything happens or you want someone to keep an extra eye on your house while you’re on vacation. It is a really nice service to have! The neighborhood really is a great, central location. Easy drives to Rice University, the medical center, the museums, downtown, Washington Ave, the Galleria, the Heights. Great walkability. I used to walk with the kids to coffee shops all the time - Common Bond is well known, there’s a great spot called Brasil, Empire Cafe is popular, and the list goes on! In the other direction, you can easily walk to Barnes & Nobles bookstore in the River Oaks Shopping Center, or everything else it has (Starbucks, Gap kids, Gap, Talbots, J Jill, Sur La Table). We’d walk to Kroger or HEB for grocery shopping, and even walk up to Buffalo Bayou park (only about a mile away). There are several closer parks, too, of course. There’s also a lot of nightlife and high-end restaurants to walk to, for those who don’t have little ones! Anvil is the best cocktail bar in the city, Poison Girl is a famous dive bar, Riel is a super fancy seafood place down the street, Vibrant is a very cool, very California new cafe just a block away. -

Why World Houston Place?

WHY WORLD HOUSTON PLACE? 15710 JOHN F KENNEDY BLVD | HOUSTON, TX 77032 • In a deed-restricted commercial park • Great access with backdoor to Beltway 8 • Down the street from George Bush Inter- continental Airport (IAH) • Employees can leave cars in garage when flying out of IAH • Large floor plates (approximately 30,000sf) • Top 3½ floors available and in move-in condition • Building signage available • Onsite property management • 24-hour onsite guard service • Onsite deli/restaurant • Conference center • Future fitness center • Garage parking of 3.5/1000 sf • Courtyard area outside LOCATION Strategically located within 30 minutes of Houston's centers of commerce, transportation and housing GEORGE BUSH 10 min MEDICAL CENTER 30 min INTERCONTINENTAL AIRPORT DOWNTOWN 14 min THE WOODLANDS 16 min GALLERIA 19 min KINGWOOD 27 min PORT OF HOUSTON 23 min KATY 29 min 99 69 249 45 90 8 290 10 10 8 610 6 610 59 90 288 CORPORATE LANDSCAPE 1 2 3 1 4 1 5 6 7 8 9 1 10 11 12 3 13 14 15 16 17 Tur key Creek 960 FM 1 45 G E O R G E B U S H I N T E R C O N T I N E N T A L A I N o r th F R P O R T o r k Gre en s B a y o u u yo Ba s n e e r G 16 11 1 7 G Gre r e ens Bayou en s B 15 5 ay o 4 u 17 10 3 14 8 8 13 9 8 2 12 6 Green s B Halls Bayou a you Greens Bayou W Fork V og el Cre e k 45 59 249 GLOBALLY CONNECTED The North Houston District provides redundant fiber as I-45 North and Beltway 8 is the hub of where all fiber comes into Houston so tenants will receive faster internet speeds 6 DATA CENTERS / LIT BUILDINGS 9 LONG HAUL NETWORKS AT&T Earthlink Level -

±4 Acres in Garden Oaks W TC Jester Blvd, Houston, TX 77018

DOWNTOWN HOUSTON · 6 MILES Employment Entertainment Hosts 12 of Houston’s 26 Fortune 500 Houston Theater District companies Minute Maid Park Major Employers (Number of Employees) (Houston Astros) Chevron (7,000) Toyota Center (Houston Shell Oil Company (6,500 Rockets) Chase Bank (4,695) George R. Brown KBR (3,175) Convention Center ExxonMobil Corporation (3,000) Discovery Green Park El Paso Corporation (2,200) CenterPoint Energy (2,040) Hess Corporation (1,870 United Airlines (1,840) GREATER HEIGHTS Wells Fargo (1,695) American Legion Park LAZYBOOK/TIMBERGROVE Gatlin's BBQ ELLA BLVD Union Kitchen 610 Toasted Mattress One Paws Pet Resort Oak Forest Swimming Pool JUDIWAY ST Oaks Dad’s Club W 34TH ST OAK FOREST DR » W TC JESTER BLVD GARDEN OAKS « ROSSLYN RD | E TC JESTER BLVD ±4.0ACRES FUTURE ROW DU BARRY LN OAK FOREST/GARDEN OAKS Home Prices up to $1.3M TC Jester Park ±4 Acres in Garden Oaks W TC Jester Blvd, Houston, TX 77018 OFFERING MEMORANDUM Contacts Tim Dosch Becky Hand Dosch Marshall Real Estate Principal Senior Associate 713.955.3120 [email protected] [email protected] O 713-955-3127 O 713-955-3121 777 Post Oak Blvd Houston, TX 77056 M 713-459-8123 M 918-629-5592 www.dmreland.com Exclusive Representation David Marshall Dillon Mills Dosch Marshall Real Estate (DMRE) has been exclu- sively retained to represent the Seller in the disposition Principal Senior Associate of ±4 acres between W TC Jester Blvd and E TC Jester [email protected] [email protected] Blvd at Judiway St, Houston Garden Oaks, TX 77018 O 713-955-3126 O 713-955-3123 (Property). -

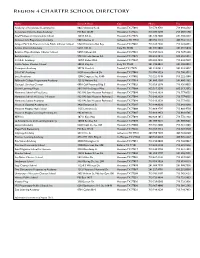

Region 4 CHARTER SCHOOL DIRECTORY

Region 4 CHARTER SCHOOL DIRECTORY Name Street Address City Phone Fax Academy of Accelerated Learning, Inc. 6025 Chimney Rock Houston, TX 77081 713.773.4766 713.666.2532 Accelerated Intermediate Academy PO Box 20589 Houston, TX 77225 713.283.6298 713.283.6190 Alief Montessori Community School 12013 6th St. Houston, TX 77072 281.530.9406 281.530.2233 Ambassadors Preparatory Academy 5001 Avenue U Galveston, TX 77551 409.762.1115 409.762.1114 Amigos Por Vida-Friends for Life Public Charter School 5503 El Camino Del Rey Houston, TX 77081 713.349.9945 713.349.0671 Aristoi Classical Academy 5618 11th St. Katy, TX 77493 281.391.5003 281.391.5010 Beatrice Mayes Institute Charter School 5807 Calhoun Rd. Houston, TX 77021 713.747.5629 713.747.5683 Beta Academy 9701 Almeda Genoa Rd. Houston, TX 77075 832.656.5841 832.656.5841 C.O.R.E. Academy 12707 Cullen Blvd. Houston, TX 77047 832.483.9596 713.436.7099 Calvin Nelms Charter School 20625 Clay Rd. Katy, TX 77449 281.398.8031 281.398.8032 Comquest Academy 207 N. Peach St. Tomball, TX 77375 281.516.0611 281.516.9807 D.R.A.W. Academy 3920 Stoney Brook Dr. Houston, TX 77063 713.706.3729 713.706.3711 Excel Academy 1200 Congress, Ste. 6500 Houston, TX 77002 713.222.4340 713.222.4388 Fallbrook College Preparatory Academy 12512 Walters Rd. Houston, TX 77014 281.880.1360 281.880.1362 George I. Sanchez Charter 6001 Gulf Freeway, Bldg. E Houston, TX 77023 713.929.2378 713.926.8035 Global Learning Village 3015 N. -

BVSW GARDEN OAKS, L.P., a Texas Limited Partnership Authorized to Transact Business in the State of Texas ("Owner")

TAX ABATEMENT AGREEMENT e iL 4 7 4 4 3 This TAX ABATEMENT AGREEMENT ("Agreement") is made by and between the CITY OF HOUSTON, TEXAS, a municipal corporation and home-rule city ("City"), and BVSW GARDEN OAKS, L.P., a Texas limited partnership authorized to transact business in the State of Texas ("Owner"). The City and the Owner may be referred to singularly as "Party" and collectively as the "Parties." Capitalized terms have the meanings defined in the first section of this Agreement. WITNESSETH: WHEREAS, the encouragement of new and existing development and investment in the City is paramount to the City's continued economic development; and WHEREAS, in accordance with the requirements of Section 44-127(a)-(c) of the Code of Ordinances of the City of Houston, Texas ("Code"), the Owner desires to renovate, modernize, and redevelop a "residential facility" as defined in Section 44-121 of the Code ("Facility") to be used and occupied as multi-family housing accommodations by residential tenants; and WHEREAS, in accordance with Section 44-123 of the Code, the Owner filed a written application for tax abatement dated March 14, 2012 and has been working with the City regarding the subject Real Property since June 15, 2011; and WHEREAS, the City Council finds that it is reasonably likely that Owner, if granted the tax abatement described in this Agreement, will rehabilitate, renovate and modernize the existing, deteriorated, substandard structures in the BVSW Garden Oaks, L.P. Tax Abatement Reinvestment Zone ("Zone") which will benefit property