La Colonia Mexicana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Journal of the Central Plains Volume 37, Number 3 | Autumn 2014

Kansas History A Journal of the Central Plains Volume 37, Number 3 | Autumn 2014 A collaboration of the Kansas Historical Foundation and the Department of History at Kansas State University A Show of Patriotism German American Farmers, Marion County, June 9, 1918. When the United States formally declared war against Onaga. There are enough patriotic citizens of the neighborhood Germany on April 6, 1917, many Americans believed that the to enforce the order and they promise to do it." Wamego mayor war involved both the battlefield in Europe and a fight against Floyd Funnell declared, "We can't hope to change the heart of disloyal German Americans at home. Zealous patriots who the Hun but we can and will change his actions and his words." considered German Americans to be enemy sympathizers, Like-minded Kansans circulated petitions to protest schools that spies, or slackers demanded proof that immigrants were “100 offered German language classes and churches that delivered percent American.” Across the country, but especially in the sermons in German, while less peaceful protestors threatened Midwest, where many German settlers had formed close- accused enemy aliens with mob violence. In 1918 in Marion knit communities, the public pressured schools, colleges, and County, home to a thriving Mennonite community, this group churches to discontinue the use of the German language. Local of German American farmers posed before their tractor and newspapers published the names of "disloyalists" and listed threshing machinery with a large American flag in an attempt their offenses: speaking German, neglecting to donate to the to prove their patriotism with a public display of loyalty. -

Hispanic Archival Collections Houston Metropolitan Research Cent

Hispanic Archival Collections People Please note that not all of our Finding Aids are available online. If you would like to know about an inventory for a specific collection please call or visit the Texas Room of the Julia Ideson Building. In addition, many of our collections have a related oral history from the donor or subject of the collection. Many of these are available online via our Houston Area Digital Archive website. MSS 009 Hector Garcia Collection Hector Garcia was executive director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations, Diocese of Galveston-Houston, and an officer of Harris County PASO. The Harris County chapter of the Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations (PASO) was formed in October 1961. Its purpose was to advocate on behalf of Mexican Americans. Its political activities included letter-writing campaigns, poll tax drives, bumper sticker brigades, telephone banks, and community get-out-the- vote rallies. PASO endorsed candidates supportive of Mexican American concerns. It took up issues of concern to Mexican Americans. It also advocated on behalf of Mexican Americans seeking jobs, and for Mexican American owned businesses. PASO produced such Mexican American political leaders as Leonel Castillo and Ben. T. Reyes. Hector Garcia was a member of PASO and its executive secretary of the Office of Community Relations. In the late 1970's, he was Executive Director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations for the Diocese of Galveston-Houston. The collection contains some materials related to some of his other interests outside of PASO including reports, correspondence, clippings about discrimination and the advancement of Mexican American; correspondence and notices of meetings and activities of PASO (Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations of Harris County. -

I the Sacred Act of Reading: Spirituality, Performance, And

The Sacred Act of Reading: Spirituality, Performance, and Power in Afro-Diasporic Literature By Anne Margaret Castro Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in English August, 2016 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Vera Kutzinski, Ph.D. Ifeoma Nwankwo, Ph.D. Hortense Spillers, Ph.D. Marzia Milazzo, Ph.D. Victor Anderson, Ph.D. i Copyright © 2016 by Anne Margaret Castro All Rights Reserved To Annette, who taught me the steps. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am deeply grateful for the generous mentoring I have received throughout my graduate career from my committee chairs, Vera Kutzinski and Ifeoma Nwankwo. Your support and attention to this project’s development has meant the world to me. My scholarship has been enriched by the support and insight of my committee members: Hortense Spillers, Marzia Milazzo, and Victor Anderson. I would also like to express my thanks to Kathryn Schwarz and Katie Crawford, who always treated my work as valuable. This dissertation is a testament to the encouragement and feedback I received from my colleagues in the Vanderbilt English department. Thanks to Vera Kutzinski’s generosity of time and energy, I have had the pleasure of growing through sustained scholarly engagement with Tatiana McInnis, Lucy Mensah, RJ Boutelle, Marzia Milazzo and Aubrey Porterfield. I am thankful to Ifeoma Nwankwo’s work with the Drake Fellowship, which gave me the opportunity to conduct oral history interviews with Dr. Erna Brodber and Petal Samuel, in Woodside, Jamaica. My experiences in Jamaica deeply affected the way I approach my scholarship. -

Los Veteranos—Latinos in WWII

Los Veteranos—Latinos in WWII Over 500,000 Latinos (including 350,000 Mexican Americans and 53,000 Puerto Ricans) served in WWII. Exact numbers are difficult because, with the exception of the 65th Infantry Regiment from Puerto Rico, Latinos were not segregated into separate units, as African Americans were. When war was declared on December 8, 1941, thousands of Latinos were among those that rushed to enlist. Latinos served with distinction throughout Europe, in the Pacific Theater, North Africa, the Aleutians and the Mediterranean. Among other honors earned, thirteen Medals of Honor were awarded to Latinos for service during WWII. In the Pacific Theater, the 158th Regimental Combat Team, of which a large percentage was Latino and Native American, fought in New Guinea and the Philippines. They so impressed General MacArthur that he called them “the greatest fighting combat team ever deployed in battle.” Latino soldiers were of particular aid in the defense of the Philippines. Their fluency in Spanish was invaluable when serving with Spanish speaking Filipinos. These same soldiers were part of the infamous “Bataan Death March.” On Saipan, Marine PFC Guy Gabaldon, a Mexican-American from East Los Angeles who had learned Japanese in his ethnically diverse neighborhood, captured 1,500 Japanese soldiers, earning him the nickname, the “Pied Piper of Saipan.” In the European Theater, Latino soldiers from the 36th Infantry Division from Texas were among the first soldiers to land on Italian soil and suffered heavy casualties crossing the Rapido River at Cassino. The 88th Infantry Division (with draftees from Southwestern states) was ranked in the top 10 for combat effectiveness. -

Siete Lenguas: the Rhetorical History of Dolores Huerta and the Rise of Chicana Rhetoric Christine Beagle

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository English Language and Literature ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2016 Siete Lenguas: The Rhetorical History of Dolores Huerta and the Rise of Chicana Rhetoric Christine Beagle Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/engl_etds Recommended Citation Beagle, Christine. "Siete Lenguas: The Rhetorical History of Dolores Huerta and the Rise of Chicana Rhetoric." (2016). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/engl_etds/34 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Language and Literature ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Garcia i Christine Beagle Candidate English, Rhetoric and Writing Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Michelle Hall Kells, Chairperson Irene Vasquez Natasha Jones Melina Vizcaino-Aleman Garcia ii SIETE LENGUAS: THE RHETORICAL HISTORY OF DOLORES HUERTA AND THE RISE OF CHICANA RHETORIC by CHRISTINE BEAGLE B.A., English Language and Literature, Angelo State University, 2005 M.A., English Language and Literature, Angelo State University, 2008 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ENGLISH The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico November 10, 2015 Garcia iii DEDICATION To my children Brandon, Aliyah, and Eric. Your brave and resilient love is my savior. I love you all. Garcia iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, to my dissertation committee Michelle Hall Kells, Irene Vasquez, Natasha Jones, and Melina Vizcaino-Aleman for the inspiration and guidance in helping this dissertation project come to fruition. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Houston Chronicle Index to Mexican American Articles, 1901-1979

AN INDEX OF ITEMS RELATING TO MEXICAN AMERICANS IN HOUSTON AS EXTRACTED FROM THE HOUSTON CHRONICLE This index of the Houston Chronicle was compiled in the Spring and summer semesters of 1986. During that period, the senior author, then a Visiting Scholar in the Mexican American Studies Center at the University of Houston, University Park, was engaged in researching the history of Mexican Americans in Houston, 1900-1980s. Though the research tool includes items extracted for just about every year between 1901 (when the Chronicle was established) and 1970 (the last year searched), its major focus is every fifth year of the Chronicle (1905, 1910, 1915, 1920, and so on). The size of the newspaper's collection (more that 1,600 reels of microfilm) and time restrictions dictated this sampling approach. Notes are incorporated into the text informing readers of specific time period not searched. For the era after 1975, use was made of the Annual Index to the Houston Post in order to find items pertinent to Mexican Americans in Houston. AN INDEX OF ITEMS RELATING TO MEXICAN AMERICANS IN HOUSTON AS EXTRACTED FROM THE HOUSTON CHRONICLE by Arnoldo De Leon and Roberto R. Trevino INDEX THE HOUSTON CHRONICLE October 22, 1901, p. 2-5 Criminal Docket: Father Hennessey this morning paid a visit to Gregorio Cortez, the Karnes County murderer, to hear confession November 4, 1901, p. 2-3 San Antonio, November 4: Miss A. De Zavala is to release a statement maintaining that two children escaped the Alamo defeat. History holds that only a woman and her child survived the Alamo battle November 4, 1901, p. -

George I. Sanchez and the Civil Rights Movement: 1940-1960

George I. Sanchez and the Civil Rights Movement: 1940-1960 Ricardo Romo* This article is a tribute to Dr. George I. Sanchez and examines the important contributions he made in establishing the American Council of Spanish-Speaking People (ACSSP) in 1951. The ACSSP funded dozens of civil rights cases in the Southwest during the early 1950's and repre- sented the first large-scale effort by Mexican Americans to establish a national civil rights organization. As such, ACSSP was a precursor of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) and other organizations concerned with protecting the legal rights of Mexican Americans in the Southwest. The period covered here extends from 1940 to 1960, two crucial decades when Mexican Ameri- cans made a concerted effort to challenge segregation in public schools, discrimination in housing and employment, and the denial of equal ac- cess to public places such as theaters, restaurants, and barber shops. Although Mexican Americans are still confronted today by de facto seg- regation and job discrimination, it is of historical and legal interest that Mexican American legal victories, in areas such as school desegregation, predated by many years the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education and the civil rights movement of the 1960's. Sanchez' pioneering leadership and the activities of ACSSP merit exami- nation if we are to fully comprehend the historical struggle of the Mexi- can American civil rights movement. In a recent article, Karen O'Conner and Lee Epstein traced the ori- gins of MALDEF to the 1960's civil rights era.' The authors argued that "Chicanos early on recongized their inability to seek rights through traditional political avenues and thus sporadically resorted to litigation .. -

Mexican American History Resources at the Briscoe Center for American History: a Bibliography

Mexican American History Resources at the Briscoe Center for American History: A Bibliography The Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin offers a wide variety of material for the study of Mexican American life, history, and culture in Texas. As with all ethnic groups, the study of Mexican Americans in Texas can be approached from many perspectives through the use of books, photographs, music, dissertations and theses, newspapers, the personal papers of individuals, and business and governmental records. This bibliography will familiarize researchers with many of the resources relating to Mexican Americans in Texas available at the Center for American History. For complete coverage in this area, the researcher should also consult the holdings of the Benson Latin American Collection, adjacent to the Center for American History. Compiled by John Wheat, 2001 Updated: 2010 2 Contents: General Works: p. 3 Spanish and Mexican Eras: p. 11 Republic and State of Texas (19th century): p. 32 Texas since 1900: p. 38 Biography / Autobiography: p. 47 Community and Regional History: p. 56 The Border: p. 71 Education: p. 83 Business, Professions, and Labor: p. 91 Politics, Suffrage, and Civil Rights: p. 112 Race Relations and Cultural Identity: p. 124 Immigration and Illegal Aliens: p. 133 Women’s History: p. 138 Folklore and Religion: p. 148 Juvenile Literature: p. 160 Music, Art, and Literature: p. 162 Language: p. 176 Spanish-language Newspapers: p. 180 Archives and Manuscripts: p. 182 Music and Sound Archives: p. 188 Photographic Archives: p. 190 Prints and Photographs Collection (PPC): p. 190 Indexes: p. -

WOMEN of MEXICAN HERITAGE in DOUGLAS, ARIZONA by Cecelia

Breaking Borders: Women of Mexican Heritage in Douglas, Arizona Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Lewis, Cecelia Ann Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 11/10/2021 07:37:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/620954 BREAKING BORDERS: WOMEN OF MEXICAN HERITAGE IN DOUGLAS, ARIZONA by Cecelia Ann Lewis __________________________ Copyright © Cecelia Ann Lewis A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF MEXICAN AMERICAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2016 1 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Cecelia Lewis, titled Breaking Borders: Women of Mexican Heritage in Douglas, Arizona and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________________________________________________Date: 9 June 2016 Lydia Otero ______________________________________________________________Date: 9 June 2016 Anna O’Leary ______________________________________________________________Date: 9 June 2016 Raquel Rubio Goldsmith _____________________________________________________________ Date: 9 June 2016 Damián Baca ______________________________________________________________Date: 9 June 2016 Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Felix Tijerina

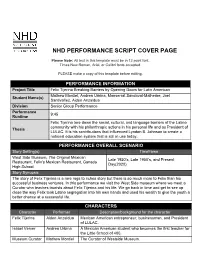

NHD PERFORMANCE SCRIPT COVER PAGE Please Note: All text in this template must be in 12 point font. Times New Roman, Arial, or Calibri fonts accepted. PLEASE make a copy of this template before editing. PERFORMANCE INFORMATION Project Title Felix Tijerina Breaking Barriers by Opening Doors for Latin American Mathew Montiel, Andrea Urbina, Monserrat Sandoval-Malherbe, Joel Student Name(s) Santivañez, Aiden Anzaldua Division Senior Group Performance Performance 9:45 Runtime Felix Tijerina tore down the social, cultural, and language barriers of the Latino community with his philanthropic actions in his personal life and as President of Thesis LULAC. It is his contributions that influenced Lyndon B. Johnson to create a national education system that is still in use today. PERFORMANCE OVERALL SCENARIO Story Setting(s) Timeframe West Side Museum, The Original Mexican Late 1920’s, Late 1950’s, and Present Restaurant, Felix’s Mexican Restaurant, Ganado Day(2020) High School Story Synopsis The story of Felix Tijerina is a rare rags to riches story but there is so much more to Felix than his successful business ventures. In this performance we visit the West Side museum where we meet a Curator who teaches tourists about Felix Tijerina and his life. We go back in time and get to see up close the way Felix took Latino segregation into his own hands and used his wealth to give the youth a better chance at a successful life. CHARACTERS Character Performer Description/background for the character Felix Tijerina Aiden Anzaldua Mexican American entrepreneur, businessman, and President of LULAC. Isabel Verver Andrea Urbina A Mexican American student who becomes the first teacher for the Little School of 400. -

THE ROLE of THIRD-PARTY FUNDERS in the DEVELOPMENT of MEXICAN AMERICAN INTEREST GROUP ADVOCACY by Devin Fernandes

CONSTRUCTING THE CAUSE: THE ROLE OF THIRD-PARTY FUNDERS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF MEXICAN AMERICAN INTEREST GROUP ADVOCACY by Devin Fernandes A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY © Devin Fernandes 2018 All rights reserved ABSTRACT For the last 25 years, scholars have raised alarms over the disappearance of local civic membership organizations since the 1960s and a concomitant explosion of third-party-funded, staff-dominated, professional advocacy organizations. This change is said to contribute to long- term declines in civic and political participation, particularly among minorities and low income Americans, and by extension, diminished electoral fortunes of the Democratic Party. Rather than mobilize mass publics and encourage their political participation, the new, largely progressive advocacy groups finance themselves independently through foundation grant money and do most of their work in Washington where they seek behind the scenes influence with unelected branches of government. However, in seeking to understand this transition “from membership to advocacy,” most current scholarship focuses on the socio-political factors that made it possible. We have little understanding of the internal dynamics sustaining individual organizations themselves to account for why outside-funded groups are able to emerge and thrive or the ways in which dependence on external subsidies alters their operating incentives. To address this hole in the literature, the dissertation engages in a theory-building effort through a case study analysis of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF), founded in 1968. Drawing on archival materials from MALDEF and its primary benefactor, the Ford Foundation, the dissertation opens the black box of internal decision-making to understand in real time how resource dependence on non-beneficiaries shaped the maintenance calculus of its leaders and in turn, group behavior.