The Economic Impact of Globalisation in Indonesia*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Stavros Niarchos Foundation Lecture Brochure

STRAINED BEDFELLOWS: WHAT WE CAN DO TO MAKE OPEN ECONOMIES INCLUSIVE Tharman Shanmugaratnam SINGAPORE’S DEPUTY PRIME MINISTER AND COORDINATING MINISTER FOR ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL POLICIES Eighteenth Annual Stavros Niarchos Foundation Lecture and Dinner Wednesday, May 30, 2018 Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Deputy Prime Minister of Singapore ABOUT THE STAVROS NIARCHOS FOUNDATION LECTURE SERIES The annual Stavros Niarchos Foundation Lecture Series at the Peterson Institute for International Economics was established in 2001 through the generous support of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation. The Series enables the Institute to present a world leader of economic policy and thought for a major address each year on a topic of central concern to the US and international policy communities. The Stavros Niarchos Foundation [(SNF) (www.SNF.org)] is one of the world’s leading private, international philanthropic organizations, making grants in the areas of arts and culture, education, health and sports, and social welfare. Since 1996, the Foundation has committed more than $2.5 billion, through more than 4,000 grants to nonprofit organizations in 124 nations around the world. The SNF funds organizations and projects, worldwide, that aim to achieve a broad, lasting and positive impact, for society at large, and exhibit strong leadership and sound management. The Foundation also supports projects that facilitate the formation of public-private partnerships as an effective means for serving public welfare. Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Deputy Prime Minister of Singapore Eighteenth Annual Stavros Niarchos Foundation Lecture and Dinner 3 PROGRAM 5:30 pm WELCOME Dr. Adam S. Posen PRESIDENT, PETERSON INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL ECONOMICS Michael A. Peterson CHAIRMAN, BOARD OF DIRECTORS, PETERSON INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL ECONOMICS Mr. -

A Abdullah Ali, 227, 288, 350, 359, 390 Abdurrahman Wahid (Gus Dur)

INDEX A anti-Chinese riots, 74, 222–23, 381–84, Abdullah Ali, 227, 288, 350, 359, 390 393 Abdurrahman Wahid (Gus Dur), 245, see also Malari riots; May 1998 riots 269, 416, 417, 429–32, 434–35, Anthony (Anthoni) Salim, see Salim, 438–39, 444, 498, 515 Anthony Aburizal Bakrie, 393, 399, 402 Apkindo (Indonesian Wood Panel Achmad Thahir, 200 Association), 4 Achmad Tirtosudiro, 72, 166–67 Aquino, Cory, 460–61 Adam Malik, 57, 139, 164–66 Arbamass Multi Invesco, 341 Adi Andoyo, 380 Ari H. Wibowo Hardojudanto, 340 Adi Sasono, 400, 408 Arief Husni, 71, 91 Adrianus Mooy, 246 Arifin Siregar, 327 Agus Lasmono, 113 Army Strategic Reserve Command Agus Nursalim, 91 (Kostrad), 56, 59, 64, 72–73, 108, Ahmad Habir, 299 111, 116, 166, 171, 176, 209 Akbar Tanjung, 257, 393, 395 Argha Karya Prima, 120–21 Alamsjah Ratu Prawiranegara, 65–66, Argo Manunggal Group, 34 68, 69, 72 A.R. Soehoed, 328 “Ali Baba” relationship, 50 ASEAN (Association of Southeast Ali Murtopo, 57, 60, 65–66, 69–70, Asian Nations), 155, 362, 498 73–75, 117, 153, 222–23, 326 AsiaMedic, 474 Ali Sadikin, 224, 238–39 Asian financial crisis, 33, 85, 87, 113, Ali Wardhana, 329, 393 121–23, 130, 147, 193, 228, 248, American Express Bank, 192, 262, 276, 284, 286, 290–91, 311, 329, 271 336, 349, 352, 354–67, 369, 392, Amex Bancom, 262–64 405, 466, 468, 473, 480 Amien Rais, 381, 387–88 Aspinall, Edward, 496 Ando, Koki, 410–11 Association of Indonesian Muslim Ando, Momofuku, 292, 410 Intellectuals (ICMI), 379 Andreas Harsono, 351 Association of Southeast Asian Andrew Riady, 225 Nations, see ASEAN -

An Indonesian Perspective Mari Elka Pangestu March 2015

THE NEW ECONOMY, DEVELOPMENT AND REFORM: AN INDONESIAN PERSPECTIVE Mari Elka Pangestu 2015 Harold Mitchell Development Policy Lecture THE HAROLD MITCHELL DEVELOPMENT POLICY LECTURE SERIES Timor-Leste and the New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States Emilia Pires November 2012 The challenges of aid dependency and economic reform: Africa and the Pacific Jim Adams November 2013 The new economy, development and reform: an Indonesian perspective Mari Elka Pangestu March 2015 Other publications in this series are available to download at devpolicy.anu.edu.au. THE NEW ECONOMY, DEVELOPMENT AND REFORM: AN INDONESIAN PERSPECTIVE Mari Elka Pangestu 2015 Harold Mitchell Development Policy Lecture DEVELOPMENT POLICY CENTRE 2015 Harold Mitchell Development Policy Annual Lecture The new economy, development and reform – an Indonesian perspective Mari Elka Pangestu Abstract This is the 2015 Annual Harold Mitchell Development Policy Lecture, delivered by Professor Mari Elka Pangestu on March 12, 2015. The Annual Harold Mitchell Development Policy Lecture, of which this is the third, was created to provide a forum at which the most pressing development issues can be addressed by the best minds and most influential practitioners of our time. The 2015 lecture was presented by the Development Policy Centre in collaboration with the ANU Indonesia Project and the Australia-Indonesia Centre. All Harold Mitchell Development Policy Lectures are available from devpolicy.anu.edu.au, under publications. Professor Mari Elka Pangestu was the Minister of Trade of Indonesia from October 2004 to October 2011. She was appointed to the newly created position of Minister of Tourism and Creative Economy in October 2011. Professor Pangestu is currently Professor of International Economics at the University of Indonesia. -

RI Shows Off Culture in Davos

RI shows off culture in Davos Linda Yulisman, The Jakarta Post, Davos | Headlines | Sat, January 25 2014, 10:59 AM White summit: The view of Davos with the Congress Center in the early morning of the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum (WEF) 2014 in Davos, Switzerland, on Friday. The annual Davos gathering, which draws thousands of the world’s most powerful people, will welcome more than 40 heads of state and government this year to focus on questions about the world’s future, organizers said on Wednesday. (Reuters/Ruben Sprich) Indonesia is using “cultural diplomacy” to promote trade, investment and tourism at the prestigious annual World Economic Forum (WEF), running from Wednesday until Saturday in Davos, Switzerland. The forum is being attended by 2,500 officials and captains of industries from around the world. The Trade Ministry teamed up with the Investment Coordinating Board (BKPM) to hold an Indonesia Night at the Morosani Schweizerhoff Hotel on Thursday to display the country’s rich cultural heritage through cuisine, fashion, jewelry, dance, traditional cosmetics and spa, and other arts products. The event, under the banner of Remarkable Indonesia, was attended by more than 300 officials and business executives, including WEF founder and executive chairman Klaus Schwab, Finance Minister Chatib Basri, Tourism and Creative Economy Minister Mari Elka Pangestu, Foreign Minister Marty Natalegawa, BKPM chief Mahendra Siregar and Bank Indonesia Governor Agus Martowardojo. Top Indonesian business leaders, including Bank Mandiri president director Budi Gunadi Sadikin, Bakrie Group CEO Anindya Bakrie, James Riady and John Riady of the Lippo Group and Indika Energy president director Wishnu Wardhana, were also present at the event. -

Chineseness Is in the Eye of the Beholder

CHINESENESS IS IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER: THE TRANSFORMATION OF CHINESE INDONESIAN AFTER REFORMASI A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School Of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Setefanus Suprajitno August 2013 © 2013 Setefanus Suprajitno CHINESENESS IS IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER: THE TRANSFORMATION OF CHINESE INDONESIAN AFTER REFORMASI Setefanus Suprajitno, Ph.D. Cornell University 2013 My dissertation is an ethnographic project documenting the transformation of Chinese Indonesians post-Suharto Indonesia. When Suharto was in power (1966–1998), the Chinese in his country were not considered an ethnicity with the freedom to maintain their ethnic and cultural heritage. They were marked as “the Other” by various policies and measures that suppressed their cultural markers of ethnicity. The regime banned Chinese language education, prohibited Chinese media, and dissolved Chinese organizations, an effort that many Chinese thought of as destroying the Chinese community in Indonesia as they were seen as the three pillars that sustained the Chinese community. Those efforts were intended to make the Chinese more Indonesian; ironically, they highlighted the otherness of Chinese Indonesians and made them perpetual foreigners who remained the object of discrimination despite their total assimilation into Indonesian society. However, the May 1998 anti-Chinese riot that led to the fall of the New Order regime brought about political and social reform. The three pillars of the Chinese community were restored. This restoration produces new possibilities for Chinese cultural expression. Situated in this area of anthropological inquiry, my dissertation examines how the Chinese negotiate and formulate these identities, and how they ascribe meaning to Chinese identities. -

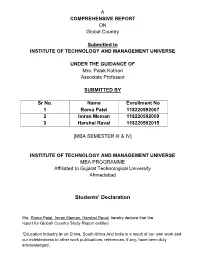

Students' Declaration

A COMPREHENSIVE REPORT ON Global Country Submitted to INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT UNIVERSE UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF Mrs. Palak Kothari Associate Professor SUBMITTED BY Sr No. Name Enrollment No 1 Roma Patel 118220592007 2 Imran Meman 118220592009 3 Harshal Raval 118220592015 [MBA SEMESTER III & IV] INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT UNIVERSE MBA PROGRAMME Affiliated to Gujarat Technological University Ahmedabad Students’ Declaration We, Roma Patel, Imran Meman, Harshal Raval, hereby declare that the report for Global/ Country Study Report entitled “Education Industry in on China, South Africa And India is a result of our own work and our indebtedness to other work publications, references, if any, have been duly acknowledged. Place : Vadodara (Signature) Date : ( Name Of Student) Roma Patel Imran Meman Harshal Raval Preface As a MBA student of ITM Universe, Vadodara. Affiliated by GTU. we have made report on Global Country Report on Education sector. So we have selected China , India, South Africa To study the Education sector. We have taken all the topics shown in the report to study the sector. We have learnt a lot from this report about Education In all three countries. The policy and norms of all three country also mentioned in the report. The future challenges also mentioned in the report. We thankful to our head of Department Dr. S. K. Vij to helping us to make report and also to Mrs. Palak Kothari. We the help of our faculty member we made this report. 2 This report will help in future. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT It is our pleasure to place on record my sincere gratitude towards Mrs. -

Banking in ASEAN

THE COMPASS MARCH 2017 ISSUE #3 IN THIS ISSUE Economic and Political Fragmentation Global Trend Malaysian Prime Minister Launches the Jeffrey Sachs Center on Sustainable Development Sustainability A Time For Integration Banking in ASEAN Retaining International Economic Order ASEAN and East Asia Improving Education Access and Quality in Asia Asia Public Policy Forum 2017 SUNWAY UNIVERSITY (KPT/JPT/DFT/US/B15) A member of the Sunway Education Group Tel. (03) 7491 8622 Email. [email protected] Web. sunway.edu.my OWNED AND GOVERNED BY THE JEFFREY CHEAH FOUNDATION (800946-T) IN THIS ISSUE INTERNATIONAL ACADEMIC ADVISORY COUNCIL (IAAC) ESSAYS Page 7 HRH Sultan Dr Nazrin Shah Ibni Dr Mari Elka Pangestu ASEAN and East Asia are the Key to Sultan Azlan Muhibbuddin Shah Former Minister of Trade; Tourism & Retaining the Current International Economic Order The Sultan of Perak Darul Ridzuan; Creative Economy, Indonesia; former Royal Patron, Jeffrey Cheah Institute Executive Director of the Center for Page 9 on Southeast Asia Strategic & International Studies in TABLE OF CONTENT TABLE Vitality of Research-Inspired Teaching in Jakarta; and Professor, Malaysian Universities Professor Dwight Perkins Universitas Indonesia PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Page 12 Chairman, IAAC of Jeffrey Cheah Banking in ASEAN- A Time for Integration Institute on Southeast Asia; Professor Anthony Saich Page 16 Harold Hitchings Burbank Professor Professor, Kennedy School of Emeritus of Political Economy, Government, Harvard University As a Matter of Fact, All Facts Are Conditional -

Global Future Council on the Future of International Trade and Investment

Global Future Council on the Future of International Trade and Investment Strategic Brief for the Annual Meeting of Stewards of International Trade and Investment From Bad to Worse? whereas global trade values grew twice as fast as global GDP in the three decades up to 2008, they have since The Case for Arresting the Slide in underperformed GDP growth. Global Trade Cooperation Two and a half years ago, failure to agree or ratify mega- regionals might have meant forgoing further liberalisation, but keeping the status quo. Today we face the risk of a Amid growing discontent over globalisation, the outlook permanent shift backwards: from a “rules-based system” for global trade cooperation is darkening, with very serious generally respected by all, to a “deals-based system” in implications for economic growth, peace, and stability. which powerful countries look to stretch or even break the Below we set out a diagnosis of the problems, and three rules to maximise national advantage, at the expense of brief, derivative, scenarios outlining how the future could weaker players. unfold. We hold to the optimistic scenario and, in this light, Cooperating on trade is harder than it used to be. Twenty the document is intended to be a “call to arms” for the years of deep structural change in both advanced and World Economic Forum’s Global Trade Stewards, and to emerging economies have complicated the politics of governments and business at large. jobs, growth, and making compromises in international Two years on, a very different picture for trade negotiating fora. The shifting balance of global economic power – itself partly a product of the open global economy’s In August 2015, the last World Economic Forum Global success – has produced what was dubbed a ‘G-Zero world’ Agenda Council on Trade and Foreign Direct Investment at Davos 2011. -

Appendix: List of People Interviewed

APPENDIX: LIST OF PEOPlE INTERVIEWED Subronto Laras (President Commissioner of Indomobil Group, Salim Group; Chairman of Indonesian Employers Association, Apindo; Board of Advisor of Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Kadin), Jakarta. Gandi Sulistiyanto (Managing Director of Sinar Mas Group; Vice Chairman of Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Kadin), Jakarta. Emmy Kuswandari (Corporate Affairs and Communication, President Office, Sinar Mas Group), Jakarta. Dato’ Sri Dr. Tahir (Founder and Chairman of Mayapada Group), Jakarta. Suryo Bambang Sulisto (President Commissioner of Bumi Resources, Bakrie Group; Chairman, Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Kadin; Chairman of the Indonesian Indigenous Businessman’s Association, HIPPI), Jakarta. Sandiaga Salahudin Uno (Founder and President Director of Saratoga Investama Sedaya; Vice Chairman of Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Kadin; now Vice Governor of Jakarta), Jakarta. Chris Kanter (Chairman of Sigma Sembada Group; Vice Chairman, Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Kadin; Board of Advisor, Indonesian Employers Association, Apindo; Senior Advisor to Indonesian Minister of Trade), Jakarta. © The Author(s) 2019 223 F. Al-Fadhat, The Rise of International Capital, Critical Studies of the Asia-Pacific, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3191-6 224 APPENDIX: LIST OF PEOPLE INTERVIEWED Dr. Yandi Djajadiningrat (Bramadi Capital; Secretary General, Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Kadin, ASEAN Committee), Jakarta. Anton J. Supit (President Commissioner of Sierad Group; Chairman, Indonesian Employers Association, Apindo), Jakarta. Dr. Fadhil Hasan (Executive Director of Indonesian Palm Oil Association, GAPKI); Supervisory Board of Bank Indonesia), Jakarta. Soetrisno Bachir (Founder and Chairman of Sabira Group; Chairman of National Mandate Party (PAN) 2005–2010), Jakarta. -

Indonesia's Economic Diplomacy of Creative Economy Under Susilo

Indonesia’s Economic Diplomacy of Creative Economy Under Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono Administration Toward Indonesia’s National Income (Study Case: Craft Export Indonesia to United States 2011-2014) By GALUH ATIKASURI ID No. 016201400066 A Thesis presented to President University The Faculty of Humanities in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Bachelor Degree in International Relations Concentration of Diplomacy Studies 2019 THESIS ADVISER RECOMMENDATION LETTER This thesis entitled “Indonesia’s Economic Diplomacy of Creative Economy Under Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono Toward Indonesia’s National Income (Study Case: Craft Export Indonesia to United States 2011-2014)” prepared and submitted by Galuh Atikasuri in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in International Relations from the Faculty of Humanities has been reviewed and found to have satisfied the requirements for a thesis fit to be examined. I therefore recommend this thesis for Oral Defense. Cikarang, Indonesia, January 29th 2019 Recommended and Acknowledged by, Riski M Baskoro, S.Sos.,M.A i ii iii ABSTRACT Galuh Atikasuri, 016201400066, International Relations 2014, President University Thesis Title: Indonesia’s Economic Diplomacy of Creative Economy Under Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono Toward Indonesia’s National Income (Study Case: Craft Export Indonesia to United States 2011-2014) Creative Economy is one of the programs from the government of Indonesia that relies on ideas, creativity and innovation derived from human resources and it is the main production factor. During the Presidency of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY), Indonesia adopted the slogan “a thousand friends, zero enemy” on Indonesia’s foreign policy, where the slogan means that Indonesia focused on increasing partnerships with other countries in the stand up for its national interests. -

The Challenges for Trade Policy in a Dynamic World and Regional Setting: an Indonesian Perspective Mari Pangestu

The Challenges for Trade Policy in a Dynamic World and Regional Setting: An Indonesian Perspective Mari Pangestu Richard Snape Lecture 22 November 2010 Melbourne © Commonwealth of Australia 2011 ISBN 978-1-74037-341-8 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, the work may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source. Reproduction for commercial use or sale requires prior written permission from the Commonwealth. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Attorney-General’s Department, National Circuit, Canberra ACT 2600 or posted at www.ag.gov.au/cca. This publication is available in hard copy or PDF format from the Productivity Commission website at www.pc.gov.au. If you require part or all of this publication in a different format, please contact Media and Publications (see below). Publications Inquiries: Media and Publications Productivity Commission Locked Bag 2 Collins Street East Melbourne VIC 8003 Tel: (03) 9653 2244 Fax: (03) 9653 2303 Email: [email protected] General Inquiries: Tel: (03) 9653 2100 or (02) 6240 3200 An appropriate citation for this paper is: Pangestu, M. 2010, The Challenges for Trade Policy in a Dynamic World and Regional Setting: An Indonesian Perspective, Richard Snape Lecture, 22 November, Productivity Commission, Melbourne. JEL code: F130 The Productivity Commission The Productivity Commission is the Australian Government’s independent research and advisory body on a range of economic, social and environmental issues affecting the welfare of Australians. -

The Big Picture: Indonesia's Partnership with U.S. Investors

Investment Report November 2017 The Big Picture: Indonesia’s Partnership with U.S. Investors The Big Picture: Indonesia’s Partnership with U.S. Investors Author Jet Damazo Santos Editor A. Lin Neumann Associate Editors Arian Ardie John Goyer Hayat Indriyatno Mary Regina Silaban AmCham Indonesia and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, 2017 © copyright reserved Indonesia Today – 2045 Population (in million) Today 2024 2045 264 282 317 GDP ($ Trillion) Today 0.933 2024 1.4 – 1.7 2045 9.1 Per capita income $28,700 $3,600 $5,000 —$6,000 Today 2024 2045 Sources: Interviews, Badan Pusat Statistik, The World Bank 1 Contents Executive Summary Moving From Vision to Reality 01 The Big Challenge 02 Indonesia’s Road Map 03 Hurdles to High Growth 04 Analysis of Sectors 05 Recommendations Contents For the fifth year of the U.S.-Indonesia Investment Initiative, we sat down with key policymakers, business leaders and top analysts to try to determine what the big picture for Indonesia is, how the government plans to achieve it, and the challenges standing in its way. 04 By 2024, the current administration hopes to see Indonesia well on its way to escaping the middle-income trap. By its 100th year as an independent nation in 2045, Indonesia aims to become a high-income country and among the top 10 largest economies in the world. 08 To achieve its goals, Indonesia wants to move away from being an economy heavily dependent on raw commodity exports and consumption, toward one driven by value-added manufacturing and modern services, fueled by heavy infrastructure development and increased domestic and foreign investment.