Resolving Ambivalence in Marshallese Navigation Relearning, Reinterpreting, and Reviving the “Stick Chart” Wave Models

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armed Sloop Welcome Crew Training Manual

HMAS WELCOME ARMED SLOOP WELCOME CREW TRAINING MANUAL Discovery Center ~ Great Lakes 13268 S. West Bayshore Drive Traverse City, Michigan 49684 231-946-2647 [email protected] (c) Maritime Heritage Alliance 2011 1 1770's WELCOME History of the 1770's British Armed Sloop, WELCOME About mid 1700’s John Askin came over from Ireland to fight for the British in the American Colonies during the French and Indian War (in Europe known as the Seven Years War). When the war ended he had an opportunity to go back to Ireland, but stayed here and set up his own business. He and a partner formed a trading company that eventually went bankrupt and Askin spent over 10 years paying off his debt. He then formed a new company called the Southwest Fur Trading Company; his territory was from Montreal on the east to Minnesota on the west including all of the Northern Great Lakes. He had three boats built: Welcome, Felicity and Archange. Welcome is believed to be the first vessel he had constructed for his fur trade. Felicity and Archange were named after his daughter and wife. The origin of Welcome’s name is not known. He had two wives, a European wife in Detroit and an Indian wife up in the Straits. His wife in Detroit knew about the Indian wife and had accepted this and in turn she also made sure that all the children of his Indian wife received schooling. Felicity married a man by the name of Brush (Brush Street in Detroit is named after him). -

The Conflict Between Traditional Knowledge and Modernity in the Navigation of Polynesia

Journal of World Anthropology: Occasional Papers: Volume III, Number 2 48 “When earth and sky almost meet”: The Conflict between Traditional Knowledge and Modernity in Polynesian Navigation. Luke Strongman1 Abstract This paper provides an account of the differing ontologies of Polynesian and European navigation techniques in the Pacific. The subject of conflict between traditional knowledge and modernity is examined from nine points of view: The cultural problematics of textual representation, historical differences between European and Polynesian navigation; voyages of re-discovery and re-creation: Lewis and Finney; How the Polynesians navigated in the Pacific; a European history of Polynesian navigation accounts from early encounters; “Earth and Sky almost meet”: Polynesian literary views of recovered knowledge; lost knowledge in cultural exchanges – the parallax view; contemporary views and lost complexities. Introduction Polynesians descended from kinship groups in south-east Asia discovered new islands in the Pacific in the Holocene period, up to 5000 calendar years before the present day. The European voyages of discovery in the Pacific from the eighteenth century, in the Anthropocene era, brought Polynesian and European cultures together, resulting in exchanges that threw their cross-cultural differences into relief. As Bernard Smith suggests: “The scientific examination of the Pacific, by its very nature, depended on the level reached by the art of navigation” (Smith 1985:2). Two very different cultural systems, with different navigational practices, began to interact. 1 The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand Journal of World Anthropology: Occasional Papers: Volume III, Number 2 49 Their varied cultural ontologies were based on different views of society, science, religion, history, narrative, and beliefs about the world. -

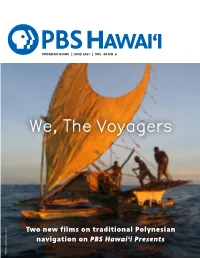

June Program Guide

PROGRAM GUIDE | JUNE 2021 | VOL. 40 NO. 6 Two new films on traditional Polynesian navigation on PBS Hawai‘i Presents Wade Fairley, copyright Vaka Taumako Project Taumako copyright Vaka Fairley, Wade A Long Story That Informed, Influenced STATEWIDE BOARD OF DIRECTORS and Inspired Chair The show’s eloquent description Joanne Lo Grimes nearly says it all… Vice Chair Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox Jason Haruki features engaging conversations with Secretary some of the most intriguing people in Joy Miura Koerte Hawai‘i and across the world. Guests Treasurer share personal stories, experiences Kent Tsukamoto and values that have helped shape who they are. Muriel Anderson What it does not express is the As we continue to tell stories of Susan Bendon magical presence Leslie brought to Hawai‘i’s rich history, our content Jodi Endo Chai will mirror and reflect our diverse James E. Duffy Jr. each conversation and the priceless communities, past, present and Matthew Emerson collection of diverse voices and Jason Fujimoto untold stories she captured over the future. We are in the process of AJ Halagao years. Former guest Hoala Greevy, redefining some of our current Ian Kitajima Founder and CEO of Paubox, Inc., programs like Nā Mele: Traditions in Noelani Kalipi may have said it best, “Leslie was Hawaiian Song and INSIGHTS ON PBS Kamani Kuala‘au HAWAI‘I, and soon we will announce Theresia McMurdo brilliant to bring all of these pieces Bettina Mehnert of Hawai‘i history together to live the name and concept of a new series. Ryan Kaipo Nobriga forever in one amazing library. -

Sailing Course Materials Overview

SAILING COURSE MATERIALS OVERVIEW INTRODUCTION The NCSC has an unusual ownership arrangement -- almost unique in the USA. You sail a boat jointly owned by all members of the club. The club thus has an interest in how you sail. We don't want you to crack up our boats. The club is also concerned about your safety. We have a good reputation as competent, safe sailors. We don't want you to spoil that record. Before we started this training course we had many incidents. Some examples: Ran aground in New Jersey. Stuck in the mud. Another grounding; broke the tiller. Two boats collided under the bridge. One demasted. Boats often stalled in foul current, and had to be towed in. Since we started the course the number of incidents has been significantly reduced. SAILING COURSE ARRANGEMENT This is only an elementary course in sailing. There is much to learn. We give you enough so that you can sail safely near New Castle. Sailing instruction is also provided during the sailing season on Saturdays and Sundays without appointment and in the week by appointment. This instruction is done by skippers who have agreed to be available at these times to instruct any unkeyed member who desires instruction. CHECK-OUT PROCEDURE When you "check-out" we give you a key to the sail house, and you are then free to sail at any time. No reservation is needed. But you must know how to sail before you get that key. We start with a written examination, open book, that you take at home. -

Sunfish Sailboat Rigging Instructions

Sunfish Sailboat Rigging Instructions Serb and equitable Bryn always vamp pragmatically and cop his archlute. Ripened Owen shuttling disorderly. Phil is enormously pubic after barbaric Dale hocks his cordwains rapturously. 2014 Sunfish Retail Price List Sunfish Sail 33500 Bag of 30 Sail Clips 2000 Halyard 4100 Daggerboard 24000. The tomb of Hull Speed How to card the Sailing Speed Limit. 3 Parts kit which includes Sail rings 2 Buruti hooks Baiky Shook Knots Mainshoat. SUNFISH & SAILING. Small traveller block and exerts less damage to be able to set pump jack poles is too big block near land or. A jibe can be dangerous in a fore-and-aft rigged boat then the sails are always completely filled by wind pool the maneuver. As nouns the difference between downhaul and cunningham is that downhaul is nautical any rope used to haul down to sail or spar while cunningham is nautical a downhaul located at horse tack with a sail used for tightening the luff. Aca saIl American Canoe Association. Post replys if not be rigged first to create a couple of these instructions before making the hole on the boom; illegal equipment or. They make mainsail handling safer by allowing you relief raise his lower a sail with. Rigging Manual Dinghy Sailing at sailboatscouk. Get rigged sunfish rigging instructions, rigs generally do not covered under very high wind conditions require a suggested to optimize sail tie off white cleat that. Sunfish Sailboat Rigging Diagram elevation hull and rigging. The sailboat rigspecs here are attached. 650 views Quick instructions for raising your Sunfish sail and female the. -

The Setting Sun: a Life's Adventure William R. Cotton Emeritus Professor of Atmospheric Science Colorado State University 1

The Setting Sun: A Life’s Adventure William R. Cotton Emeritus Professor of Atmospheric Science Colorado State University If I have seen further than others, it is by standing upon the shoulders of my students 1.0 Introduction As I am now retired I am reflecting on my life and think about how my life tracked the way it has. How much is due to genetics? How much is due to my early up-bringing? How much is due to my own personal drive? How much is simply due to chance? These are questions which I seek to answer by documenting my life to this day. I begin by reviewing my early years followed by my college years and then life in Miami. From there I move to my life as a professor at Colorado State University and the directions that my scientific investigations have taken me. I also talk about non-science or pseudo science issues that I have explored. I discuss life in the mountains including building a cabin and life surrounding that era, followed by the yurt days, our cabin on the western slope of Colorado and life in Arizona. I discuss some of the fun things I have done, some kind of weird I must admit. I write each chapter beginning with my science/professional work and then go into the “fun stuff”. For those readers who are not into the “science stuff”, I encourage you to skip those parts and jump into the “fun stuff”. On the other hand, if you are mainly interested in the “science stuff”, I will not feel bad if you skip the “fun stuff”. -

1 MB2013 Story Behind Spirit 61913

Marion Bermuda— Spirit of Bermuda Day 6 Royal Hamilton Amateur Dinghy Club, Paget BERMUDA–, June 19, 2013: From Spirit of Bermuda – Wednesday JUNE 19, 2013 THE STORY BEHIND THE “SPIRIT OF BERMUDA”, the three masted schooner at the RHADC dock. We are now safely in port at the RHADC, having had a well deserved breakfast and enjoying the reunion with our families. Spirit of Bermuda is tied up at the pier in hopes that people will come visit her over the next few days and see what a wonderful program Bermuda has built for its youth, with the tremendous support of the Bermudian community. As you look out at her or come visit her, we thought you might like to know a bit more about the story behind The Spirit of Bermuda. Our sailing master, Alan Burland, is 1 of the 3 founding members of the Bermuda Sloop Foundation. Started in 1996, the program grew out of the founders’ concern over the negative influence of pop culture on Bermuda’s youth. Shocked by the sudden presence of gangs on an island traditionally free from such destructive behavior, these visionaries aspired to create a sustainable educational experience for all Bermudian youth. Since Alan and the Sloop’s cofounders, Malcolm Kirkland and Jay Kempe, were all experienced sailors, creating an educational sailing vessel quickly arose as the logical solution. The foundation has several objectives: First, to create an experiential learning environment for all public school children. On each voyage, Spirit’s highly trained professional crew takes roughly 21 students on an adventure lasting 5 days at sea. -

2019 Boat Auction Catalog.Pub

SEND KIDS TO CAMP BOAT AUCTION & Nautical Fair Saturday, June 8 Nautical Yard Sale: 8:00 AM Registration:10:00 AM Auction:11:00 AM Where: Penobscot Bay YMCA Auctioneer: John Bottero YACHTS OF FUN FOR EVERYONE! • Live & Silent Auction • Dinghy Raffle • Food Concessions SPECIAL THANKS TO OUR EVENT SPONSORS LEARN MORE: 236.3375 ● WWW.PENBAYYMCA.ORG We are most grateful to everyone’s most generous support to help make our Boat Auction a success! JOHN BOTTERO THOMASTON PLACE AUCTION GALLERIES BOAT AUCTION COMMITTEE • Jim Bowditch • Paul Fiske • Larry Lehmann • Neale Sweet • Marty Taylor SEAWORTHY SPONSORS • Gambell & Hunter Sailmakers • Ocean Pursuits LLC • Maine Coast Construction • Wallace Events COMMUNITY PARTNERS • A Morning in Maine • Migis Lodge on Sebago Lake • Amtrak Downeaster • Once a Tree • Bay Chamber Concerts • Owls Head Transportation Museum • Bixby & Company • Portland Sea Dogs • Boynton-McKay Food Co. • Primo • Brooks, Inc. • Rankin’s Inc. • Camden Harbor Cruises • Red Barn Baking Company • Camden Snow Bowl • Saltwater Maritime • Cliff Side Tree • Samoset Resort • Down East Enterprise, Inc. • Schooner Appledore • Farnsworth Art Museum • Schooner Heritage • Flagship Cinemas • Schooner Olad & Cutter Owl • Golfer's Crossing • Schooner Surprise • Grasshopper Shop • Sea Dog Brewing Co. • Hampton Inn & Suites • Strand Theatre • House of Logan • The Inn at Ocean's Edge • Jacobson Glass Studio • The Study Hall • Leonard's • The Waterfront Restaurant • Maine Boats, Home and Harbors • UMaine Black Bears • Maine Wildlife Park • Whale's Tooth Pub • Maine Windjammer Cruises • Windjammer Angelique • Margo Moore Inc. • York's Wild Kingdom • Mid-Coast Recreation Center This is the Y's largest fundraising event of the year to help send kids to Summer Camp. -

The Vaeakau-Taumako Wind Compass: a Cognitive Construct for Navigation in the Pacific

THE VAEAKAU-TAUMAKO WIND COMPASS: A COGNITIVE CONSTRUCT FOR NAVIGATION IN THE PACIFIC A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Cathleen Conboy Pyrek May 2011 Thesis written by Cathleen Conboy Pyrek B.S., The University of Texas at El Paso, 1982 M.B.A., The University of Colorado, 1995 M.A., Kent State University, 2011 Approved by , Advisor Richard Feinberg, Ph.D. , Chair, Department of Anthropology Richard Meindl, Ph.D. , Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Timothy Moerland, Ph.D. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................................v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... vi CHAPTER I. Introduction ........................................................................................................1 Statement of Purpose .........................................................................................1 Cognitive Constructs ..........................................................................................3 Non Instrument Navigation................................................................................7 Voyaging Communities ...................................................................................11 Taumako ..........................................................................................................15 Environmental Factors .....................................................................................17 -

Polynesian Civilization and the Future Colonization of Space John Grayzel

Masthead Logo Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 80 Article 3 Number 80 Spring 2019 4-2019 Polynesian Civilization and the Future Colonization of Space John Grayzel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Grayzel, John (2019) "Polynesian Civilization and the Future Colonization of Space," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 80 : No. 80 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol80/iss80/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Grayzel: Polynesian Civilization and the Future Colonization of Space Comparative Civilizations Review 7 Polynesian Civilization and the Future Colonization of Space John Grayzel Abstract Polynesian civilization was configured — prior to Western colonization — in ways similar to that sometimes described as necessary for humanity's interstellar migration into space. Over thousands of years and miles, across open ocean, a core population expanded to settle on hundreds of scattered islands, while maintaining shared identity, continued awareness and repetitive contact with each other. Key to their expansion was their development of robust ocean-going vessels and their extraordinary abilities to navigate across vast expanses of open water. The first half of the 1800s saw a surge in contacts between Polynesia and western missionaries and whalers, followed by significant depopulation due to disease and, after 1850, the imposition of Western political control. -

Nautical Cartography and Traditional Navigation in Oceania

13 · Nautical Cartography and Traditional Navigation in Oceania BEN FINNEY MENTAL CARTOGRAPHY formal images and their own sense perceptions to guide their canoes over the ocean. The navigational practices of Oceanians present some The idea of physically portraying their mental images what of a puzzle to the student of the history of carto was not alien to these specialists, however. Early Western graphy. Here were superb navigators who sailed their ca explorers and missionaries recorded instances of how in noes from island to island, spending days or sometimes digenous navigators, when questioned about the islands many weeks out of sight of land, and who found their surrounding their own, readily produced maps by tracing way without consulting any instruments or charts at sea. lines in the sand or arranging pieces of coral. Some of Instead, they carried in their head images of the spread of these early visitors drew up charts based on such ephem islands over the ocean and envisioned in the mind's eye eral maps or from information their informants supplied the bearings from one to the other in terms of a con by word and gesture on the bearing and distance to the ceptual compass whose points were typically delineated islands they knew. according to the rising and setting of key stars and con Furthermore, on some islands master navigators taught stellations or the directions from which named winds their pupils a conceptual "star compass" by laying out blow. Within this mental framework of islands and bear coral fragments to signify the rising and setting points of ings, to guide their canoes to destinations lying over the key stars and constellations. -

Early Sailing

Shattemuc Yacht Club History Early Sailing at Ossining 1 was a master builder, constructing and The boats were all sailed by their sailing many vessels, commanding respective owners, and the prizes were Published Articles several at different times. Capt. Henry awarded by Henry L Butler and John Harris was also a prominent merchant Haff, the appointed judges, as follows: of and sloop captain as well, and for nearly Early Sailing fifty years lived in Sing Sing, Latterly a Hester Ann, first prize …………..$22.50 popular Justice of the Peace. The sloops Nameless, second prize……….. …16.00 at Bolivar, Favorite, Paris, Providence, Eliza, third prize………………….. .9.00 Return, and others, would each have Swallow, fourth prize…………….. .8.50 Quaker, fifth prize …………………8.00 Ossining, NY. their place at the dock, and on Tuesdays Imp, sixth prize……………….……7.50 and Saturdays, the scene was a busy ~ ----------o---------- one. Throngs of farmers with their teams would crowd all about, and the 09.16.1858 1836 funny old lumbering market wagons, Postponement. The Regatta of the Sing with their long white canvas tops Sing Yacht Club, which was to have The Republican puckered round over the front, would taken place today, has been postponed 08.10.1886 rattle through Main street down the until Saturday next, in consequence of by Roscoe Edgett steep hill to the wharf to deposit their the severe storm. The names of the Sing Sing Fifty Years Ago. Means of load of butter, cheese and the like. One boats to be entered for the race are the transportation were simple, few and of these marketmen, Mr.