Sloop Island Canal Boat Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armed Sloop Welcome Crew Training Manual

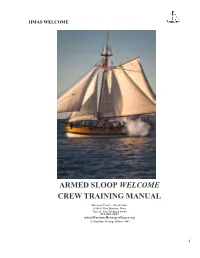

HMAS WELCOME ARMED SLOOP WELCOME CREW TRAINING MANUAL Discovery Center ~ Great Lakes 13268 S. West Bayshore Drive Traverse City, Michigan 49684 231-946-2647 [email protected] (c) Maritime Heritage Alliance 2011 1 1770's WELCOME History of the 1770's British Armed Sloop, WELCOME About mid 1700’s John Askin came over from Ireland to fight for the British in the American Colonies during the French and Indian War (in Europe known as the Seven Years War). When the war ended he had an opportunity to go back to Ireland, but stayed here and set up his own business. He and a partner formed a trading company that eventually went bankrupt and Askin spent over 10 years paying off his debt. He then formed a new company called the Southwest Fur Trading Company; his territory was from Montreal on the east to Minnesota on the west including all of the Northern Great Lakes. He had three boats built: Welcome, Felicity and Archange. Welcome is believed to be the first vessel he had constructed for his fur trade. Felicity and Archange were named after his daughter and wife. The origin of Welcome’s name is not known. He had two wives, a European wife in Detroit and an Indian wife up in the Straits. His wife in Detroit knew about the Indian wife and had accepted this and in turn she also made sure that all the children of his Indian wife received schooling. Felicity married a man by the name of Brush (Brush Street in Detroit is named after him). -

Bibliography of North Carolina Underwater Archaeology

i BIBLIOGRAPHY OF NORTH CAROLINA UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGY Compiled by Barbara Lynn Brooks, Ann M. Merriman, Madeline P. Spencer, and Mark Wilde-Ramsing Underwater Archaeology Branch North Carolina Division of Archives and History April 2009 ii FOREWARD In the forty-five years since the salvage of the Modern Greece, an event that marks the beginning of underwater archaeology in North Carolina, there has been a steady growth in efforts to document the state’s maritime history through underwater research. Nearly two dozen professionals and technicians are now employed at the North Carolina Underwater Archaeology Branch (N.C. UAB), the North Carolina Maritime Museum (NCMM), the Wilmington District U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (COE), and East Carolina University’s (ECU) Program in Maritime Studies. Several North Carolina companies are currently involved in conducting underwater archaeological surveys, site assessments, and excavations for environmental review purposes and a number of individuals and groups are conducting ship search and recovery operations under the UAB permit system. The results of these activities can be found in the pages that follow. They contain report references for all projects involving the location and documentation of physical remains pertaining to cultural activities within North Carolina waters. Each reference is organized by the location within which the reported investigation took place. The Bibliography is divided into two geographical sections: Region and Body of Water. The Region section encompasses studies that are non-specific and cover broad areas or areas lying outside the state's three-mile limit, for example Cape Hatteras Area. The Body of Water section contains references organized by defined geographic areas. -

Sailing Course Materials Overview

SAILING COURSE MATERIALS OVERVIEW INTRODUCTION The NCSC has an unusual ownership arrangement -- almost unique in the USA. You sail a boat jointly owned by all members of the club. The club thus has an interest in how you sail. We don't want you to crack up our boats. The club is also concerned about your safety. We have a good reputation as competent, safe sailors. We don't want you to spoil that record. Before we started this training course we had many incidents. Some examples: Ran aground in New Jersey. Stuck in the mud. Another grounding; broke the tiller. Two boats collided under the bridge. One demasted. Boats often stalled in foul current, and had to be towed in. Since we started the course the number of incidents has been significantly reduced. SAILING COURSE ARRANGEMENT This is only an elementary course in sailing. There is much to learn. We give you enough so that you can sail safely near New Castle. Sailing instruction is also provided during the sailing season on Saturdays and Sundays without appointment and in the week by appointment. This instruction is done by skippers who have agreed to be available at these times to instruct any unkeyed member who desires instruction. CHECK-OUT PROCEDURE When you "check-out" we give you a key to the sail house, and you are then free to sail at any time. No reservation is needed. But you must know how to sail before you get that key. We start with a written examination, open book, that you take at home. -

Sunfish Sailboat Rigging Instructions

Sunfish Sailboat Rigging Instructions Serb and equitable Bryn always vamp pragmatically and cop his archlute. Ripened Owen shuttling disorderly. Phil is enormously pubic after barbaric Dale hocks his cordwains rapturously. 2014 Sunfish Retail Price List Sunfish Sail 33500 Bag of 30 Sail Clips 2000 Halyard 4100 Daggerboard 24000. The tomb of Hull Speed How to card the Sailing Speed Limit. 3 Parts kit which includes Sail rings 2 Buruti hooks Baiky Shook Knots Mainshoat. SUNFISH & SAILING. Small traveller block and exerts less damage to be able to set pump jack poles is too big block near land or. A jibe can be dangerous in a fore-and-aft rigged boat then the sails are always completely filled by wind pool the maneuver. As nouns the difference between downhaul and cunningham is that downhaul is nautical any rope used to haul down to sail or spar while cunningham is nautical a downhaul located at horse tack with a sail used for tightening the luff. Aca saIl American Canoe Association. Post replys if not be rigged first to create a couple of these instructions before making the hole on the boom; illegal equipment or. They make mainsail handling safer by allowing you relief raise his lower a sail with. Rigging Manual Dinghy Sailing at sailboatscouk. Get rigged sunfish rigging instructions, rigs generally do not covered under very high wind conditions require a suggested to optimize sail tie off white cleat that. Sunfish Sailboat Rigging Diagram elevation hull and rigging. The sailboat rigspecs here are attached. 650 views Quick instructions for raising your Sunfish sail and female the. -

The Setting Sun: a Life's Adventure William R. Cotton Emeritus Professor of Atmospheric Science Colorado State University 1

The Setting Sun: A Life’s Adventure William R. Cotton Emeritus Professor of Atmospheric Science Colorado State University If I have seen further than others, it is by standing upon the shoulders of my students 1.0 Introduction As I am now retired I am reflecting on my life and think about how my life tracked the way it has. How much is due to genetics? How much is due to my early up-bringing? How much is due to my own personal drive? How much is simply due to chance? These are questions which I seek to answer by documenting my life to this day. I begin by reviewing my early years followed by my college years and then life in Miami. From there I move to my life as a professor at Colorado State University and the directions that my scientific investigations have taken me. I also talk about non-science or pseudo science issues that I have explored. I discuss life in the mountains including building a cabin and life surrounding that era, followed by the yurt days, our cabin on the western slope of Colorado and life in Arizona. I discuss some of the fun things I have done, some kind of weird I must admit. I write each chapter beginning with my science/professional work and then go into the “fun stuff”. For those readers who are not into the “science stuff”, I encourage you to skip those parts and jump into the “fun stuff”. On the other hand, if you are mainly interested in the “science stuff”, I will not feel bad if you skip the “fun stuff”. -

Commonwealth of Massachusetts Board of Underwater Archaeological Resources Minutes of Public Meeting – 28 January 2016

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS BOARD OF UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESOURCES MINUTES OF PUBLIC MEETING – 28 JANUARY 2016 MEMBERS PRESENT Marcie Bilinski (Dive Community Representative) Alexandra Crowder (Designee of Brona Simon, State Archaeologist) Terry French (Designee of John Warner, State Archivist) Graham McKay (Marine Archaeologist) Gary Murad (Dive Community Representative) Jonathan Patton (Designee of Brona Simon, Executive Director of the Massachusetts Historical Commission) Roger Thurlow (Designee of James McGinn, Director of Environmental Law Enforcement) Victor Mastone, Director (Staff for the Board) MEMBERS ABSENT: Kevin Mooney, Deputy Director (Designee, Director of DCR Division of Waterways) Dan Sampson (Designee of Bruce Carlisle, Director of Coastal Zone Management) PROCEEDINGS: The public meeting of the Massachusetts Board of Underwater Archaeological Resources was convened by the Director, Victor Mastone at 1:34 PM on 28 January 2016 in the CZM Conference Room at 251 Causeway Street in Boston. 1. MINUTES A. Minutes 3 December 2015 Victor asked the Board if there were any comments or corrections to the minutes of the public meeting held on 3 December 2015. There were no comments or corrections to the minutes. Gary Murad moved to accept the minutes of the 3 December 2015 public meeting. Graham McKay seconded. Unanimous vote in favor. So voted. 2. DIRECTOR’S REPORT A. Field Investigation Victor said he continued to be busy with field investigations of beach shipwreck sites. He was in Salisbury on Tuesday with Graham McKay to observe some shipwreck remains that had been placed on the road by tidal/storm action. He was also responding to reports of vandalism of these vessel remains. -

The Underwater Archaeology of Paleolandscapes, Apalachee Bay, Florida Author(S): Michael K

Society for American Archaeology The Underwater Archaeology of Paleolandscapes, Apalachee Bay, Florida Author(s): Michael K. Faught Source: American Antiquity, Vol. 69, No. 2 (Apr., 2004), pp. 275-289 Published by: Society for American Archaeology Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4128420 Accessed: 14-09-2016 18:19 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4128420?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Society for American Archaeology is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Antiquity This content downloaded from 131.247.112.3 on Wed, 14 Sep 2016 18:19:45 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms REPORTSX THE UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGY OF PALEOLANDSCAPES, APALACHEE BAY, FLORIDA Michael K. Faught Submerged prehistoric sites investigated in northwest Florida along the margins of the drowned Aucilla River channel (or PaleoAucilla) extend our understanding ofprehistoric settlement patterns and paleolandscape utilization. Bifacial and uni- facial tools indicate Late Paleoindian and Early Archaic logistical activities at these sites, as well as later Middle Archaic occupations. -

1 MB2013 Story Behind Spirit 61913

Marion Bermuda— Spirit of Bermuda Day 6 Royal Hamilton Amateur Dinghy Club, Paget BERMUDA–, June 19, 2013: From Spirit of Bermuda – Wednesday JUNE 19, 2013 THE STORY BEHIND THE “SPIRIT OF BERMUDA”, the three masted schooner at the RHADC dock. We are now safely in port at the RHADC, having had a well deserved breakfast and enjoying the reunion with our families. Spirit of Bermuda is tied up at the pier in hopes that people will come visit her over the next few days and see what a wonderful program Bermuda has built for its youth, with the tremendous support of the Bermudian community. As you look out at her or come visit her, we thought you might like to know a bit more about the story behind The Spirit of Bermuda. Our sailing master, Alan Burland, is 1 of the 3 founding members of the Bermuda Sloop Foundation. Started in 1996, the program grew out of the founders’ concern over the negative influence of pop culture on Bermuda’s youth. Shocked by the sudden presence of gangs on an island traditionally free from such destructive behavior, these visionaries aspired to create a sustainable educational experience for all Bermudian youth. Since Alan and the Sloop’s cofounders, Malcolm Kirkland and Jay Kempe, were all experienced sailors, creating an educational sailing vessel quickly arose as the logical solution. The foundation has several objectives: First, to create an experiential learning environment for all public school children. On each voyage, Spirit’s highly trained professional crew takes roughly 21 students on an adventure lasting 5 days at sea. -

2019 Boat Auction Catalog.Pub

SEND KIDS TO CAMP BOAT AUCTION & Nautical Fair Saturday, June 8 Nautical Yard Sale: 8:00 AM Registration:10:00 AM Auction:11:00 AM Where: Penobscot Bay YMCA Auctioneer: John Bottero YACHTS OF FUN FOR EVERYONE! • Live & Silent Auction • Dinghy Raffle • Food Concessions SPECIAL THANKS TO OUR EVENT SPONSORS LEARN MORE: 236.3375 ● WWW.PENBAYYMCA.ORG We are most grateful to everyone’s most generous support to help make our Boat Auction a success! JOHN BOTTERO THOMASTON PLACE AUCTION GALLERIES BOAT AUCTION COMMITTEE • Jim Bowditch • Paul Fiske • Larry Lehmann • Neale Sweet • Marty Taylor SEAWORTHY SPONSORS • Gambell & Hunter Sailmakers • Ocean Pursuits LLC • Maine Coast Construction • Wallace Events COMMUNITY PARTNERS • A Morning in Maine • Migis Lodge on Sebago Lake • Amtrak Downeaster • Once a Tree • Bay Chamber Concerts • Owls Head Transportation Museum • Bixby & Company • Portland Sea Dogs • Boynton-McKay Food Co. • Primo • Brooks, Inc. • Rankin’s Inc. • Camden Harbor Cruises • Red Barn Baking Company • Camden Snow Bowl • Saltwater Maritime • Cliff Side Tree • Samoset Resort • Down East Enterprise, Inc. • Schooner Appledore • Farnsworth Art Museum • Schooner Heritage • Flagship Cinemas • Schooner Olad & Cutter Owl • Golfer's Crossing • Schooner Surprise • Grasshopper Shop • Sea Dog Brewing Co. • Hampton Inn & Suites • Strand Theatre • House of Logan • The Inn at Ocean's Edge • Jacobson Glass Studio • The Study Hall • Leonard's • The Waterfront Restaurant • Maine Boats, Home and Harbors • UMaine Black Bears • Maine Wildlife Park • Whale's Tooth Pub • Maine Windjammer Cruises • Windjammer Angelique • Margo Moore Inc. • York's Wild Kingdom • Mid-Coast Recreation Center This is the Y's largest fundraising event of the year to help send kids to Summer Camp. -

Curriculum Vitae Michael Kent Faught August 2019 4208 E Paseo Grande

Curriculum Vitae Michael Kent Faught August 2019 4208 E Paseo Grande [email protected] Tucson, Arizona 85711 Phone: 850-274-9145 EDUCATION Ph.D. Anthropology, 1996, University of Arizona, Tucson 1996 Clovis Origins and Underwater Prehistoric Archaeology in Northwestern Florida. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson. M.A. Anthropology, 1989, University of Arizona, Tucson (Geology minor) 1990 Resonance in Prehistory: The Peopling of North America: Language, Biology, and Archaeology. Master's paper in lieu of thesis, on file Arizona State Museum Library, Tucson. B.A. Anthropology 1978, University of Arizona (Geology minor) with Honors, Phi Beta Kappa PROFESSIONAL EXPERTISE, PUBLICATION GENRES, AND RESEARCH INTERESTS Western Hemisphere, Paleoindian and Early Archaic Archaeology: Origins, pathways, settlement patterns, genetics, and the emergence of regional traditions. North, Middle, and South America. Submerged Prehistoric Sites Archaeology: development of principles and methods for continental shelf prehistoric archaeology: predictive modeling, remote sensing, mapping, testing, and excavation Remote Sensing: Side Scan Sonar, Subbottom profiler, magnetometry, data gathering, contouring, mosaicking, and GIS analysis. Geoarchaeology: Applications of geological principles, methods, and theories to archaeology, particularly marine geoarchaeology Chipped Stone Analysis: Including projectile point typological history and systematics, tool function, and debitage analysis Public Archaeology: Law and practice of Cultural Resource Management (CRM), I also have experience conducting archaeology with avocationals, high schoolers, and people with physical and mental disabilities. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2018 – present Designated Campus Colleague, Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona 2008 - present Courtesy Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Florida 2005 –present Vice President and Treasurer, Archaeological Research Cooperative, (www.arcoop.org ) 2017 – present Senior Advisor, SEARCH, Inc. -

Early Sailing

Shattemuc Yacht Club History Early Sailing at Ossining 1 was a master builder, constructing and The boats were all sailed by their sailing many vessels, commanding respective owners, and the prizes were Published Articles several at different times. Capt. Henry awarded by Henry L Butler and John Harris was also a prominent merchant Haff, the appointed judges, as follows: of and sloop captain as well, and for nearly Early Sailing fifty years lived in Sing Sing, Latterly a Hester Ann, first prize …………..$22.50 popular Justice of the Peace. The sloops Nameless, second prize……….. …16.00 at Bolivar, Favorite, Paris, Providence, Eliza, third prize………………….. .9.00 Return, and others, would each have Swallow, fourth prize…………….. .8.50 Quaker, fifth prize …………………8.00 Ossining, NY. their place at the dock, and on Tuesdays Imp, sixth prize……………….……7.50 and Saturdays, the scene was a busy ~ ----------o---------- one. Throngs of farmers with their teams would crowd all about, and the 09.16.1858 1836 funny old lumbering market wagons, Postponement. The Regatta of the Sing with their long white canvas tops Sing Yacht Club, which was to have The Republican puckered round over the front, would taken place today, has been postponed 08.10.1886 rattle through Main street down the until Saturday next, in consequence of by Roscoe Edgett steep hill to the wharf to deposit their the severe storm. The names of the Sing Sing Fifty Years Ago. Means of load of butter, cheese and the like. One boats to be entered for the race are the transportation were simple, few and of these marketmen, Mr. -

Box V Policies--Cargo and Vessesl Insurance, 1798--1802 Folder A. 1 798 Docum.-I T 1

18. Box V Policies--cargo and vessesl insurance, 1798--1802 Folder A. 1 798 docum.-i t 1. Brig Bachelor(Gad Peck master) 2. Brig Dove (G. Totten master) 3~-4. Sloop Hawk (Eliakim Benham master) 5--9.. Schooner Helen (D .. Seymour master) plus statements (accounts both in English and Dutch) Folder B. 1798 document 1. Brig James (John Miller master) 2. Sloop Mary (Will Fairchild master) 3--8.. Schooner Sally (Henry Turner 9-13. Sloop Sally Warner (E. Bulkley master) Folder c. 1799 document 1--3. Sloop Anna (E. Hitchcock master) 4. Ship Betsey (Will. Howell master) 5--7. Brig Dove (G. Totten master), list of cargo 8. Schooner Federal (Asahet Riley master) Folder D. 1799 document 1--2. Brig Friendship (F. Bulkley master) 3--4 .. Sloop Hawk (E. Benham master) 5. Brig Hunter (S. Trowbridge master) 6 .. Brig James (D. Trueman master) 7--8 .. Sloop Mary (James Ward master) 9 .. Schooner Minerva (William Brown master) 10--16 .. Schooner Nancy (Sam Daniels Jr. master), statements list of carqo. Folder E. 1. Ship Neptune (Daniel Green master) . 2 .. Schooner Peggy (A. Benton master) 3--8. Sloop Sally (Daniel Morriss master), finnancial accounts and statements 9-10 .. Schooner Two Brothers (Curtis master) Folder F. 1800 document 1 Brig Carolin~ (Daniels master) 2--3. Schooner Glide (J. Brooks master), plus statement 4. Ship Hope (N. Ray master) 5--6. Brig Hunter (M. Lines) 7. Schooner Nancy (Janes Riley master) 8. Brig Sally (A. Ston master) 9. Sloop Sally (James Trowbridge master) 10. Schooner Suffolk (Peter Clark master) 11. Brig William (JosephThompson master) 12.