Ancient Hawaii 1 Ancient Hawaii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Hula the Origins of Hula Are Contained in Many Legends. One Story Describes the Adventures of Hi'iaka, Who Danced To

History of Hula The origins of hula are contained in many legends. One story describes the adventures of Hi'iaka, who danced to appease her fiery sister, the volcano goddess Pele and there she created Hula. This Hi'iaka story provides the basic foundation for many present-day dances. As late as the early twentieth century, ritual and prayer surrounded all aspects of hula training and practice. Teachers and students were dedicated to Laka, goddess of the hula, and appropriate offerings were made regularly. In ancient Hawaii, a time when a written language did not exist, hula and its chants played an important role in keeping history, genealogy, mythology and culture alive. With each movement – a hand gesture, step of foot, swaying of hips – a story would unfold. Through the hula, the Native Hawaiians were connected with their land and their gods. The hula was danced for protocol and social enjoyment. The songs and chants of the hula preserved Hawaii’s history and culture. When the missionaries arrived and brought Christianity, Queen Ka’ahumanu converted and deemed Hula a pagan ritual, banning it in 1830 and for many years with both Ōlelo Hawaiʻi, Hawaiian language, and Hula being suppressed or banned, the knowledge, tradition and culture of Hawai’i suffered greatly. It wasn’t until King David Kalakaua came to the throne in 1874 that Hawaiian cultural traditions were restored. Public performances of hula flourished and by the early 1900s, the hula had evolved and adapted to fit the desires of tourists and global expectations. With tourism, cabaret acts, Hollywood and the King himself, Elvis, Hula experienced a great transition to the Hula that many people imagine today. -

The Dread Taboo, Human Sacrifice, and Pearl Harbor

The Dread Taboo, Human Sacrifice, and Pearl Harbor RDKHennan The word taboo, or tabu, is well known to everyone, but it is especially interesting that it is one of but two or possibly three words from the Polynesian language to have been adopted by the English-speaking world. While the original meaning of the taboo was "Sacred" or "Set apart," usage has given it a decidedly secular meaning, and it has become a part of everyday speech all over the world. In the Hawaiian lan guage the word is "kapu," and in Honolulu we often see a sign on a newly planted lawn or in a park that reads, not, "Keep off the Grass," but, "Kapu." And to understand the history and character of the Hawaiian people, and be able to interpret many things in our modern life in these islands, one must have some knowledge of the story of the taboo in Hawaii. ANTOINETTE WITHINGTON, "The Dread Taboo," in Hawaiian Tapestry Captain Cook's arrival in the Hawaiian Islands signaled more than just the arrival of western geographical and scientific order; it was the arrival of British social and political order, of British law and order as well. From Cook onward, westerners coming to the islands used their own social civil codes as a basis to judge, interpret, describe, and almost uniformly condemn Hawaiian social and civil codes. With this condemnation, west erners justified the imposition of their own order on the Hawaiians, lead ing to a justification of colonialism and the loss of land and power for the indigenous peoples. -

Visibility Analysis of Oahu Heiau

Visibility Analysis of Oahu Heiau A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN GEOGRAPHY May 2012 By Kepa Lyman Thesis Committee: Matthew McGranaghan, Chair Hong Jiang William Chapman Keywords: heiau, intervisibility, viewshed analysis Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................................... III LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................................................................... IV INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 5 CHAPTER OUTLINE ..................................................................................................................................... 6 CHAPTER I. HAWAIIAN HEIAU ............................................................................................................ 8 HEIAU AS SYMBOL ..................................................................................................................................... 8 HEIAU AS FORTRESS ................................................................................................................................. 12 TYPES ...................................................................................................................................................... -

The Conflict Between Traditional Knowledge and Modernity in the Navigation of Polynesia

Journal of World Anthropology: Occasional Papers: Volume III, Number 2 48 “When earth and sky almost meet”: The Conflict between Traditional Knowledge and Modernity in Polynesian Navigation. Luke Strongman1 Abstract This paper provides an account of the differing ontologies of Polynesian and European navigation techniques in the Pacific. The subject of conflict between traditional knowledge and modernity is examined from nine points of view: The cultural problematics of textual representation, historical differences between European and Polynesian navigation; voyages of re-discovery and re-creation: Lewis and Finney; How the Polynesians navigated in the Pacific; a European history of Polynesian navigation accounts from early encounters; “Earth and Sky almost meet”: Polynesian literary views of recovered knowledge; lost knowledge in cultural exchanges – the parallax view; contemporary views and lost complexities. Introduction Polynesians descended from kinship groups in south-east Asia discovered new islands in the Pacific in the Holocene period, up to 5000 calendar years before the present day. The European voyages of discovery in the Pacific from the eighteenth century, in the Anthropocene era, brought Polynesian and European cultures together, resulting in exchanges that threw their cross-cultural differences into relief. As Bernard Smith suggests: “The scientific examination of the Pacific, by its very nature, depended on the level reached by the art of navigation” (Smith 1985:2). Two very different cultural systems, with different navigational practices, began to interact. 1 The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand Journal of World Anthropology: Occasional Papers: Volume III, Number 2 49 Their varied cultural ontologies were based on different views of society, science, religion, history, narrative, and beliefs about the world. -

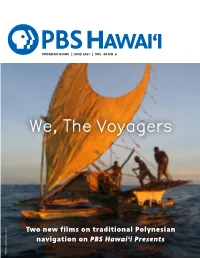

June Program Guide

PROGRAM GUIDE | JUNE 2021 | VOL. 40 NO. 6 Two new films on traditional Polynesian navigation on PBS Hawai‘i Presents Wade Fairley, copyright Vaka Taumako Project Taumako copyright Vaka Fairley, Wade A Long Story That Informed, Influenced STATEWIDE BOARD OF DIRECTORS and Inspired Chair The show’s eloquent description Joanne Lo Grimes nearly says it all… Vice Chair Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox Jason Haruki features engaging conversations with Secretary some of the most intriguing people in Joy Miura Koerte Hawai‘i and across the world. Guests Treasurer share personal stories, experiences Kent Tsukamoto and values that have helped shape who they are. Muriel Anderson What it does not express is the As we continue to tell stories of Susan Bendon magical presence Leslie brought to Hawai‘i’s rich history, our content Jodi Endo Chai will mirror and reflect our diverse James E. Duffy Jr. each conversation and the priceless communities, past, present and Matthew Emerson collection of diverse voices and Jason Fujimoto untold stories she captured over the future. We are in the process of AJ Halagao years. Former guest Hoala Greevy, redefining some of our current Ian Kitajima Founder and CEO of Paubox, Inc., programs like Nā Mele: Traditions in Noelani Kalipi may have said it best, “Leslie was Hawaiian Song and INSIGHTS ON PBS Kamani Kuala‘au HAWAI‘I, and soon we will announce Theresia McMurdo brilliant to bring all of these pieces Bettina Mehnert of Hawai‘i history together to live the name and concept of a new series. Ryan Kaipo Nobriga forever in one amazing library. -

Agriculture, Power, and Community in Kaupō, Maui

On the Cloak of Kings: Agriculture, Power, and Community in Kaupō, Maui By Alexander Underhill Baer A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Patrick V. Kirch Professor Kent G. Lightfoot Professor Anthony R. Byrne Spring 2015 On the Cloak of Kings: Agriculture, Power, and Community in Kaupō, Maui Copyright © 2015 By Alexander Underhill Baer Table of Contents List of Figures iv List of Tables viii Acknowledgements x CHAPTER I: OPENING THE WATERS OF KAUPŌ Introduction 1 Kaupō’s Natural and Historical Settings 3 Geography and Environment 4 Regional Ethnohistory 5 Plan of the Dissertation 7 CHAPTER 2: UNDERSTANDING KAUPŌ: THEORETICAL APPROACHES TO THE STUDY OF POWER AND PRODUCTION Introduction 9 Last of the Primary States 10 Of Chiefdoms and States 12 Us Versus Them: Evolutionism Prior to 1960 14 The Evolution Revolution: Evolutionism and the New Archaeology 18 Evolution Evolves: Divergent Approaches from the 1990s Through Today 28 Agriculture and Production in the Development of Social Complexity 32 Lay of the Landscape 36 CHAPTER 3: MAPPING HISTORY: KAUPŌ IN MAPS AND THE MAHELE Introduction 39 Social and Spatial Organization in Polynesia 40 Breaking with the Past: New Forms of Social Organization and Land Distribution 42 The Great Mahele 47 Historic Maps of Hawaiʻi and Kaupō 51 Kalama Map, 1838 55 Hawaiian Government Surveys and Maps 61 Post-Mapping: Kaupō Land -

Heiau and Noted Places of the Makena–Keone'ö'io Region

HEIAU AND NOTED PLACES OF THE MAKENA–KEONE‘Ö‘IO REGION OF HONUA‘ULA DESCRIBED IN HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS (1870S-1930S) This section of the study presents readers with verbatim accounts of heiau and other cultural properties as described by researchers in the region of Honua‘ula—with emphasis on the ahupua‘a of Ka‘eo—since 1916. Detailed research was conducted in collections of the Bishop Museum, Maui Historical Society, Mission Children’s Society Library-Hawaiian Historical Society, and Hawaii State Archives as a part of this study. While a significant collection of references to traditional-cultural properties and historical sites was found, only limited and inconclusive documentation pertaining to the “Kalani Heiau” (Site 196) on the Garcia family property was located. Except for documentation associated with two kuleana awarded during the Mähele of 1848, no other information pertaining to sites on the property was located in the historical accounts. In regards to the “Kalani Heiau,” the earliest reference to a heiau of that name was made in 1916, though the site was not visited, or the specific location given. It was not until 1929, that a specific location for “Kalani Heiau” was recorded by W. Walker (Walker, ms. 1930-31), who conducted an archaeological survey on Maui, for the Bishop Museum. The location of Walker’s “Site No. 196” coincides with that of the “Kalani Heiau” on the Garcia property, but it also coincides with the area claimed by Mähele Awardee, Maaweiki (Helu 3676)—a portion of the claim was awarded as a house lot for Maaweiki. While only limited information of the heiau, and other sites on the property could be located, it is clear that Site No. -

La Lei Hulu Study Guide.Indd

1906 Centennial Season 2006 05/06 Study Guide Na Lei Hulu I Ka Wekiu Friday, March 17, 2006, at 11:00 a.m. Zellerbach Hall SchoolTime Welcome March 3, 2006 Dear Educator and Students, Welcome to SchoolTime! On Friday, March 17, 2006, at 11:00 a.m., you will attend the SchoolTime performance by the dance company Na Lei Hulu I Ka Wekiu at Zellerbach Hall on the UC Berkeley campus. This San Francisco-based dance company thrills audiences with its blend of traditional and contemporary Hawaiian dance, honoring tradition while bringing hula into the modern realm. Na Lei Hulu I Ka Wekiu features a wonderful variety of hula dances from traditional to contemporary. This study guide will prepare your students for their fi eld trip to Zellerbach Hall. Your students can actively participate at the performance by: • OBSERVING how the dancers use their bodies • LISTENING to the songs and instruments that accompany the dances • THINKING ABOUT how culture is expressed through dance • REFLECTING on their experience in the theater We look forward to seeing you at Zellerbach Hall! Sincerely, Laura Abrams Rachel Davidman Director Education Programs Administrator Education & Community Programs About Cal Performances and SchoolTime The mission of Cal Performances is to inspire, nurture and sustain a lifelong appreciation for the performing arts. Cal Performances, the performing arts presenter of the University of California, Berkeley, fulfi lls this mission by presenting, producing and commissioning outstanding artists, both renowned and emerging, to serve the University and the broader public through performances and education and community programs. In 2005/06 Cal Performances celebrates 100 years on the UC Berkeley Campus. -

A Brief History of the Hawaiian People

0 A BRIEF HISTORY OP 'Ill& HAWAIIAN PEOPLE ff W. D. ALEXANDER PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM NEW YORK,: . CINCINNATI•:• CHICAGO AMERICAN BOOK C.OMPANY Digitized by Google ' .. HARVARD COLLEGELIBRAllY BEQUESTOF RCLANOBUr.ll,' , ,E DIXOII f,'.AY 19, 1936 0oPYBIGRT, 1891, BY AlilBIOAN BooK Co)[PA.NY. W. P. 2 1 Digit zed by Google \ PREFACE AT the request of the Board of Education, I have .fi. endeavored to write a simple and concise history of the Hawaiian people, which, it is hoped, may be useful to the teachers and higher classes in our schools. As there is, however, no book in existence that covers the whole ground, and as the earlier histories are entirely out of print, it has been deemed best to prepare not merely a school-book, but a history for the benefit of the general public. This book has been written in the intervals of a labo rious occupation, from the stand-point of a patriotic Hawaiian, for the young people of this country rather than for foreign readers. This fact will account for its local coloring, and for the prominence given to certain topics of local interest. Especial pains have been taken to supply the want of a correct account of the ancient civil polity and religion of the Hawaiian race. This history is not merely a compilation. It is based upon a careful study of the original authorities, the writer having had the use of the principal existing collections of Hawaiian manuscripts, and having examined the early archives of the government, as well as nearly all the existing materials in print. -

Ka Moolelo O Kauai O Kukona Ka Mo’I O Ke Aupuni O Kauai, Huiia Me Kaula, Niihau, a Me Lehua I Na KA MOOLELO KAUA‘I’S Makahiki 1400

Ka Moolelo o Kauai O Kukona ka mo’i o ke aupuni o Kauai, huiia me Kaula, Niihau, a me Lehua i na KA MOOLELO KAUA‘I’S makahiki 1400. Noloko mai no o Kukona kekahi lalani alii nana i hoomalu maluna o ka aina a hiki ia Kaumualii (hanauia 1778 a make 1824) a lilo ke aupuni ia Kamehameha i ka makahiki 1810 ma ke kuikahi mawaena o ke aupuni o Kauai a O KAUAI HERITAGE me ke aupuni o Kamehameha. O Manokalanipo ke keiki a Kukona. Oia ka mo’i i mele nui ia’i iloko o na mele e like me Nani Waialeale a me Kauai Beauty. O ke kumu o kona mele nui ia ana, no ka Holomua ka Naauao A Growing Society mea, oia ka mo’i o ka aina nei nana i kukulu i kona aupuni me ka hoonohonoho pono ana i na mahele aina like ole he moku a he ahupuaa me ka hoonoho ana i Ua holomua loa ka naauao o kanaka mamuli o ke akamai Kānaka Maoli (native Hawaiians) have lived in the area na alii maluna o kela me keia na lakou e lawelawe no ka pono o ka lahui. Mamuli o o ka noho alii ana o Manokalanipo. I kona wa i kukuluia’i surrounding Kānei‘olouma for several centuries. Upon keia papa hana, ua lako ka aina a lako ka ai a me ka i’a na kanaka. Ma ia hope mai na loko ia e like me ka mea kamaaina i keia au nei, a peia settling the area, Kānaka Maoli organized their system ikeia ka laha loa o ka maluhia maluna o ka aina a ua nui ke alohaia o ua mo’i nei. -

Historical Ethnography and Archaeology of Russian Fort Elisabeth State Historical Park, Waimea, Kaua'i

Historical Ethnography and Archaeology of Russian Fort Elisabeth State Historical Park, Waimea, Kaua'i Peter R Mills Department ofAnthropology, University ofVermont Introduction There is a sign on the highway in Waimea, Kaua'i in the Hawaiian Islands with the words "Russian Fort" printed on it. Local residents use the same term to refer to the State Historical Park that the sign marks. I give this introduction not because it is the best, but because it is the one that everyone else gets. Fort Elisabeth was built in Waimea, Kaua' i following an alliance between Kaumuali'i, paramount chief of Kaua'i, and Georg Anton Schiffer of the Russian-American Company (RAC) in 1816. Georg Schaffer and the RAC were forced to leave Kaua'i in 1817 which left Kaumuali'i in sole control of the fort. Most tourists visiting the site are surprised to fmd that Russians were building forts in the Hawaiian Islands, but the story of Fort Elisabeth and two smaller forts (Alexander and Barclay) on the north shore of Kaua'i (Figure 1) has been "well-tilled" (Barratt 1988:v) for over a century (Alexander 1894; Barratt 1988:15-24; Bolkhovitinov 1973; Bradley 1942; Emerson 1900; Golder 1930; Gronski 1928; Jarves 1844:201-203; Mazour 1937; Mehnert 1939: 22-65; Okun 1951; Pierce 1965; Tumarkin 1964:134-166; Whitney 1838:48-51). On Kaua'i, Fort Elisabeth seems to be perceived as a cumbersome and obscure monument to 19th century European expansion, lacking in any connection to traditional Hawaiian landscapes. Within the academic community, little recent attention focuses on the fort other than Richard Pierce's Russia's Hawaiian Adventure 1815-1817 (1965) with a follow-up article by Bolkhovitinov (1973). -

The History of the Hawaiian Culture August 15, 2011

Annex C – The History of the Hawaiian Culture August 15, 2011 Origins of the Ancient Hawaiians and Their Culture The first major Hawaiian island, Kauai emerged from the Pacific only six million years ago. This was millions of years before modern man walked out of Africa, but a blip in time compared to the 4.5 billion year history of our ancient planet. The Hawaiian Islands were formed above a 40 million year old volcano creating a hot spot under the Pacific Plate. As the pacific plate moves to the Northwest, the static hotspot continues to create islands. The effect of this is an island chain, one of which, the big Island, became the 5th highest island in the world. The next island in the chain, the seamount of Loihi is building and will surface in 10,000 years. The isolation of the Hawaiian Islands in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, and the wide range of environments to be found on high islands located in and near the tropics, has resulted in a vast array of endemic flora and fauna. Hawaii has more endangered species per square mile than anywhere else. Ancient tribal Polynesians arrived on this virgin scene after long, amazing sea voyages in their double-hulled canoes. The early Polynesians were an adventurous seafaring people with highly developed navigational skills. They used the sun, stars and wave patterns to find their directions. Ancient Polynesians even created incredible maps of wave patterns by binding sticks together. Bird flight paths and cloud patterns were used to discern where islands were located.