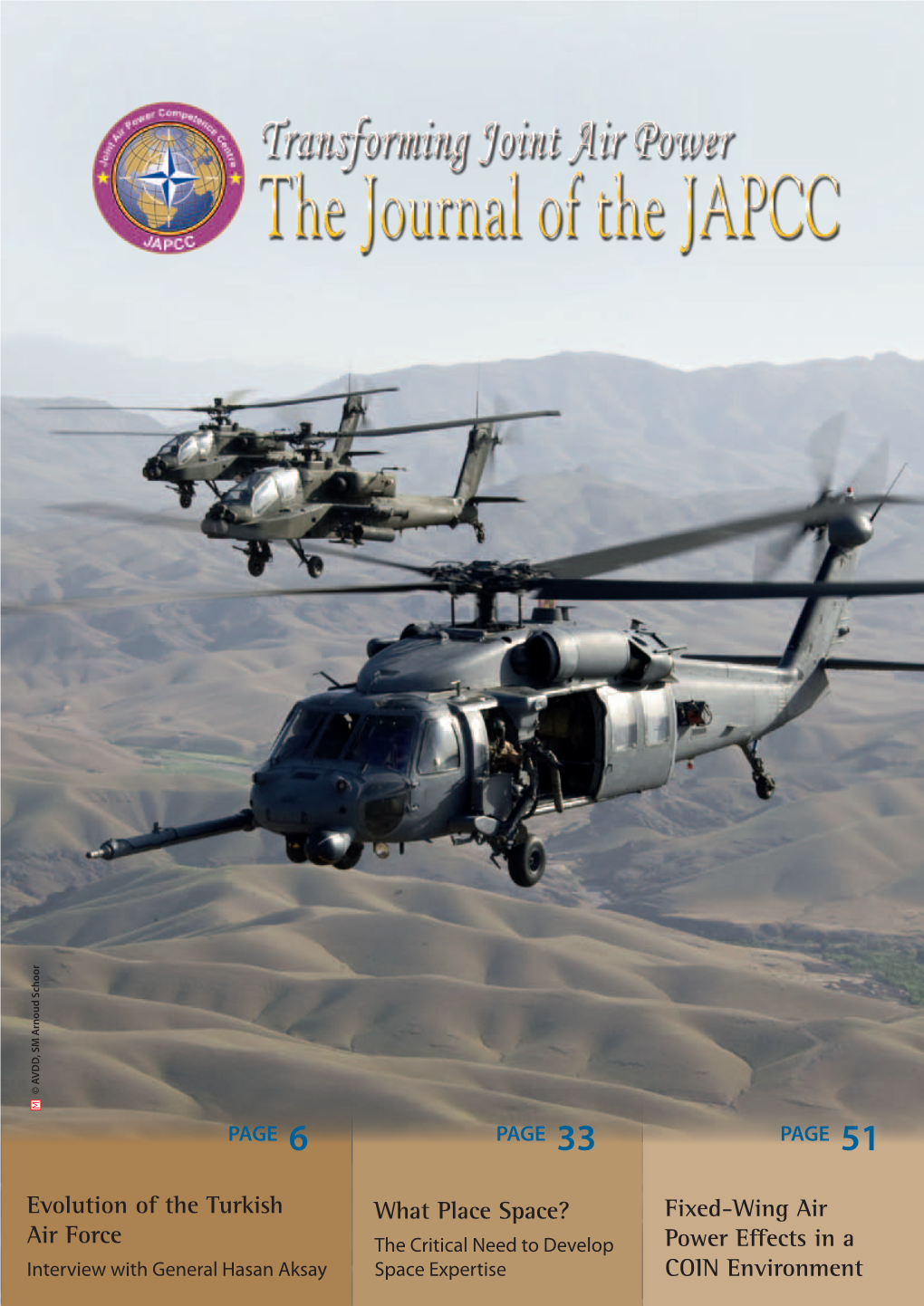

Evolution of the Turkish Air Force What Place Space?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inside This Issue: at Your Service

PR ST STD US Postage PAID Cañon City, CO Permit 56 Thursday, Feb. 17, 2005 Peterson Air Force Base, Colorado Vol. 49 No. 7 Photo courtesy of U.S. Navy Photo by Richard Cox Photo by Walt Johnson Inside This Issue: At Your Service ... 14 News Briefs ... 18 Snow Call 556-SNOW SPACE OBSERVER 2 Thursday, Feb. 17, 2005 FROM THE TOP Rumsfeld reminds troops: ‘America supports you’ By Donna Miles and women – you, to be specific – case activities happening across the ple has been overwhelming, and feed- American Forces Press Service willing to put your hand up and volun- United States supporting the troops. back from the troops is tremendous, teer to serve your country,” he said. The campaign Web site, which high- Ms. Barber said. WASHINGTON – Defense Sec- “We thank you for it, and you should lights organizations and individuals “Thanks to one and all for your retary Donald Rumsfeld sent heartfelt know in your heart that America sup- coordinating local and national sup- tremendous support, spirit and appreciation to U.S. servicemembers ports you.” port efforts, has had more than 1 mil- prayers,” a Soldier deployed to Camp recently as part of the Defense The secretary’s tribute comes on lion visitors. Slayer, Iraq, wrote on the Web site. Department’s America Supports You the heels of a popular commercial that Allison Barber, deputy assistant “We couldn’t do what we do without program and a reminder that the coun- aired during the Super Bowl in Feb. 6. secretary of defense for internal com- everyone behind us. -

1St Friday Rocks Schriever at 567-3370

COLORADO SPRINGS MILITARY NEWSPAPER GROUP Thursday, July 19, 2018 www.csmng.com Vol. 12 No. 29 Did you know? CC call addresses Airmen BACK TO SCHOOL wellness, introduces new CCC Event By Halle Thornton 50th Space Wing Public Affairs Families are invited to a back SCHRIEVER AIR FORCE BASE, Colo. — to school event July 25, 9 a.m. — Col. Jennifer Grant, commander of the 50th noon in the Schriever event center, Space Wing, hosted an all-call to address Building 20. There will be a school Schriever Airmen’s wellness and results of the bus safety demonstration, a K-9 Defense Equal Opportunity Climate Survey at demonstration, a United States Air Schriever Air Force Base, Colorado, July 12. Force Academy falcon display and However, the all-call was kicked off by an resource tables. District 22, Ellicott introduction of Chief Master Sgt. Boston schools will be in attendance to com- Alexander, command chief of the 50th SW, plete registration. The Schriever and gave him the opportunity to introduce AFB Medical Clinic has set aside himself and lay out his expectations of appointments for school physicals. Airmen. Contact the clinic’s appointment line “There is no better time to be in space, we at 524-2273 to make an appointment are the epicenter of space,” he said. “It isn’t for back to school physicals. For happening without Team Schriever. Every day more information, contact Jessica is training camp. We’re champs on a cham- Schroeder at 567-5726. pion team, and we’re the best at what we do.” Alexander expressed gratitude for the chance to serve 50th SW Airmen, and ex- Base Briefs citement for the future. -

PETE TAYLOR Partnership of Excellence Award

2018 PETE TAYLOR Partnership of Excellence Award July 23, 2018 Military Child Education Coalition 20th National Training Seminar Washington, DC MILITARY CHILD EDUCATION COALITION 909 Mountain Lion Circle Harker Heights, Texas 76548 (254) 953-1923 (254) 953-1925 fax www.MilitaryChild.org Combined Federal Campaign #10261 During his tenure as Chairman of the Military Child Education Coalition, Lieutenant General (Ret) Pete Taylor played a critical role in the establishment of partnerships between military installations and school districts serving military-connected children. In 2004, the MCEC Board of Directors established the Pete Taylor Partnership of Excellence Award in recognition of General Taylor’s work and dedication to helping America’s military children. This annual award encourages and applauds the outstanding partnerships that exist between military installations and school districts, and brings special recognition to those partnerships that demonstrate General Taylor’s long-held belief that “goodness happens at the local level.” Congratulations to the 2018 winners of the Pete Taylor Partnership of Excellence Award. www.MilitaryChild.org 1 OUTSTANDING COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIP AWARD – K-12 Restorative Practices Coalition-Colorado NAMES OF PARTNERS: • El Paso County School District 49 • Schriever Air Force Base • Peterson Air Force Base • Fort Carson • BRIGHT (Building Restorative • United States Air Force Academy Interventions Growing Honorable Traditions) The Restorative Practices Coalition includes representatives from El Paso County District 49, Peterson Air Force Base, Schriever Air Force Base, Fort Carson, United States Air Force Academy, and BRIGHT (Building Restorative Interventions Growing Honorable Traditions). This partnership supports more than 20,000 students of which more than 3,000 students have a parent or guardian actively serving on base. -

Air Force Sexual Assault Court-Martial Summaries 2010 March 2015

Air Force Sexual Assault Court-Martial Summaries 2010 March 2015 – The Air Force is committed to preventing, deterring, and prosecuting sexual assault in its ranks. This report contains a synopsis of sexual assault cases taken to trial by court-martial. The information contained herein is a matter of public record. This is the final report of this nature the Air Force will produce. All results of general and special courts-martial for trials occurring after 1 April 2015 will be available on the Air Force’s Court-Martial Docket Website (www.afjag.af.mil/docket/index.asp). SIGNIFICANT AIR FORCE SEXUAL ASSAULT CASE SUMMARIES 2010 – March 2015 Note: This report lists cases involving a conviction for a sexual assault offense committed against an adult and also includes cases where a sexual assault offense against an adult was charged and the member was either acquitted of a sexual assault offense or the sexual assault offense was dismissed, but the member was convicted of another offense involving a victim. The Air Force publishes these cases for deterrence purposes. Sex offender registration requirements are governed by Department of Defense policy in compliance with federal and state sex offender registration requirements. Not all convictions included in this report require sex offender registration. Beginning with July 2014 cases, this report also indicates when a victim was represented by a Special Victims’ Counsel. Under the Uniform Code of Military Justice, sexual assaults against those 16 years of age and older are charged as crimes against adults. The appropriate disposition of sexual assault allegations and investigations may not always include referral to trial by court-martial. -

Turkey and Black Sea Security 3

SIPRI Background Paper December 2018 TURKEY AND SUMMARY w The Black Sea region is BLACK SEA SECURITY experiencing a changing military balance. The six littoral states (Bulgaria, siemon t. wezeman and alexandra kuimova* Georgia, Romania, Russia, Turkey and Ukraine) intensified their efforts to build up their military potential after Russia’s The security environment in the wider Black Sea region—which brings takeover of Crimea and the together the six littoral states (Bulgaria, Georgia, Romania, Russia, Turkey start of the internationalized and Ukraine) and a hinterland including the South Caucasus and Moldova— civil war in eastern Ukraine is rapidly changing. It combines protracted conflicts with a significant con- in 2014. ventional military build-up that intensified after the events of 2014: Russia’s Although security in the takeover of Crimea and the start of the internationalized civil war in eastern Black Sea region has always Ukraine.1 Transnational connections between conflicts across the region been and remains important for and between the Black Sea and the Middle East add further dimensions of Turkey, the current Turkish insecurity. As a result, there is a blurring of the conditions of peace, crisis defence policy seems to be and conflict in the region. This has led to an unpredictable and potentially largely directed southwards, high-risk environment in which military forces with advanced weapons, towards the Middle East. including nuclear-capable systems, are increasingly active in close proxim- Russian–Turkish relations have been ambiguous for some years. ity to each other. Turkey has openly expressed In this context, there is an urgent need to develop a clearer understanding concern about perceived of the security dynamics and challenges facing the wider Black Sea region, Russian ambitions in the Black and to explore opportunities for dialogue between the key regional security Sea region and called for a actors. -

Realignment and Indian Air Power Doctrine

Realignment and Indian Airpower Doctrine Challenges in an Evolving Strategic Context Dr. Christina Goulter Prof. Harsh Pant Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. This article may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If it is reproduced, the Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs requests a courtesy line. ith a shift in the balance of power in the Far East, as well as multiple chal- Wlenges in the wider international security environment, several nations in the Indo-Pacific region have undergone significant changes in their defense pos- tures. This is particularly the case with India, which has gone from a regional, largely Pakistan-focused, perspective to one involving global influence and power projection. This has presented ramifications for all the Indian armed services, but especially the Indian Air Force (IAF). Over the last decade, the IAF has been trans- forming itself from a principally army-support instrument to a broad spectrum air force, and this prompted a radical revision of Indian aipower doctrine in 2012. It is akin to Western airpower thought, but much of the latest doctrine is indigenous and demonstrates some unique conceptual work, not least in the way maritime air- power is used to protect Indian territories in the Indian Ocean and safeguard sea lines of communication. Because of this, it is starting to have traction in Anglo- American defense circles.1 The current Indian emphases on strategic reach and con- ventional deterrence have been prompted by other events as well, not least the 1999 Kargil conflict between India and Pakistan, which demonstrated that India lacked a balanced defense apparatus. -

World Air Forces Flight 2011/2012 International

SPECIAL REPORT WORLD AIR FORCES FLIGHT 2011/2012 INTERNATIONAL IN ASSOCIATION WITH Secure your availability. Rely on our performance. Aircraft availability on the flight line is more than ever essential for the Air Force mission fulfilment. Cooperating with the right industrial partner is of strategic importance and key to improving Air Force logistics and supply chain management. RUAG provides you with new options to resource your mission. More than 40 years of flight line management make us the experienced and capable partner we are – a partner you can rely on. RUAG Aviation Military Aviation · Seetalstrasse 175 · P.O. Box 301 · 6032 Emmen · Switzerland Legal domicile: RUAG Switzerland Ltd · Seetalstrasse 175 · P.O. Box 301 · 6032 Emmen Tel. +41 41 268 41 11 · Fax +41 41 260 25 88 · [email protected] · www.ruag.com WORLD AIR FORCES 2011/2012 CONTENT ANALYSIS 4 Worldwide active fleet per region 5 Worldwide active fleet share per country 6 Worldwide top 10 active aircraft types 8 WORLD AIR FORCES World Air Forces directory 9 TO FIND OUT MORE ABOUT FLIGHTGLOBAL INSIGHT AND REPORT SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES, CONTACT: Flightglobal Insight Quadrant House, The Quadrant Sutton, Surrey, SM2 5AS, UK Tel: + 44 208 652 8724 Email:LQVLJKW#ÁLJKWJOREDOFRP Website: ZZZÁLJKWJOREDOFRPLQVLJKt World Air Forces 2011/2012 | Flightglobal Insight | 3 WORLD AIR FORCES 2011/2012 The French and Qatari air forces deployed Mirage 2000-5s for the fight over Libya JOINT RESPONSE Air arms around the world reacted to multiple challenges during 2011, despite fleet and budget cuts. We list the current inventories and procurement plans of 160 nations. -

Command Live Issue 12.Pdf

Free COMMAND NEWS NETWORK Issue 12 The Headlines of Today. The Battles of Tomorrow. Est – 2016 ‘Blue Homeland’ vs. ‘Greek Lake’ A HAF Mirage 2000 BGM. Long simmering tensions buzzing a helicopter carrying encounter and perhaps even A long history between Greece and Turkey the country’s defence minister unwritten ‘rules’ to reduce the This latest encounter over now threaten to explode - which had been flying over risk of an accidental. These aer- the Aegean thus has long his- into outright conflict in the Greek islands in the eastern ial provocations have resulted tory as the location of territo- Aegean. Aegean. in several dogfights between rial disputes between Greece In early May 2020 a video While the HUD tape may ap- Greek and Turkish fighters over and Turkey, which twice in 1987 surfaced of an aerial engage- pear these aircraft were engaged the years, beginning from 1974 and 1996 has almost resulted ment over the Aegean Sea - with in a real dogfight, at least one during the Turkish invasion of in outright conflict between the a Turkish Air Force F-16 caught analyst noted that the lack of a Cyprus when two Turkish F-102s two countries. In particular, the in a Greek Air Force Mirage radar lock on the Turkish F-16, were destroyed by two Greek claims and counter-claims are 2000 gunsights. The Mirages had along with it popping no flares F-5s with several losses - includ- exacerbated by the geography of reportedly intervened as these trying to escape, indicated a ing a midair collision in 2006. -

Military Police Battalion, Police Officer at Fort Carson, Colorado, on the Virtra Simulated Live-Firing Training Course, March 07, 2019

SPACE VOL. 63 NO. 13 THURSDAY, MARCH 28, 2019 OBSERVERPETERSON AIR FORCE BASE Shoot House relocation effort (U.S. Air Force photo by Cameron Hunt) PETERSON AIR FORCE BASE, Colo. — Isaac Lopez, 21st Security Forces Squadron unit trainer supervisor at Peterson Air Force Base, Colorado, instructs 1st Lt. Jake Morgan, 759th Military Police Battalion, police officer at Fort Carson, Colorado, on the VirTra simulated live-firing training course, March 07, 2019. The simulator can generate anything from urban hostage situations to desert search and reconnaissance senarios to sharpen their skills. By Cameron Hunt | 21ST SPACE WING PUBLIC AFFAIRS PETERSON AIR FORCE BASE, Colo. — The shoot house United States Space Command Commander Nominated is a 21st Security Forces Squadron training center for Peterson Air Force Base law enforcement personnel. This facility is used By Defense.gov | AIR FORCE SPACE COMMAND PUBLICAPRIL AFFAIRS 2019 by 21st SFS Airmen and civilian law enforcement personnel to train and hone their skills as law enforcement professionals. PETERSON AIR FORCE BASE, tional security. The USSPACECOM The shoot house was created reutilizing the old Peterson Colo. — The President has nomi- establishment will accelerate our AFB Military Exchange building after it was shut down. nated to the Senate Gen John W. space capabilities to address the rap- The demolition of the current shoot house was planned to "Jay" Raymond as the Commander, idly evolving threats to U.S. space sys- make room for a new lodging complex in 2020. United States Space Command tems, and the importance of deterring The shoot house demolition will impact the training (USSPACECOM).Recreationpotential adversaries from putting and capabilities of the 21st SFS. -

Medium Support Helicopter Aircrew Training Facility (MSHATF)

Medium Support Helicopter Aircrew Training Facility (MSHATF) Introduction to CAE’s MSHATF The Medium Support Helicopter Aircrew Training Facility (MSHATF) was developed by CAE in partnership with the UK Ministry of Defence. Responsible for the design, construction and financing of the facility that opened in 1999, CAE operates the MSHATF under a 40-year private finance initiative (PFI) contract. CAE’s MSHATF is delivering the total spectrum of synthetic aircrew training demanded by the UK Joint Helicopter Command Support Helicopter Force. The turnkey training program includes academic classroom training and simulator training delivered by experienced instructors. The MSHATF is equipped with six full-mission simulators configured for CH-47 Chinook, AW101 Merlin and Puma helicopters. Under the terms of its PFI contract, CAE also has the ability to provide turnkey training to third-party users. This enables approved military and civil operators across the globe to take advantage of the advanced simulation, training and mission rehearsal capability at the MSHATF on a highly cost-effective basis. Other NATO nations and wider alliances also regard the MSHATF as part of their normal training regime. For example, Royal Netherlands Air Force Chinook crews routinely train alongside their Royal Air Force (RAF) counterparts before operational deployments. In addition, Royal Navy crews operating the UK Merlin and other operators of the AW101 helicopter such as the Royal Canadian Air Force, Royal Danish Air Force, and Portuguese Air Force use the advanced Merlin simulators for a range of training applications, including battlefield and search and rescue (SAR) roles. The MSHATF also offers Puma helicopter training where the customer base includes the RAF and several Middle Eastern customers. -

Airman Posthumously Receives Medal of Honor

COMMANDER’S CORNER: HIGH-TOUCH LEADERSHIP - PAGE 2 Peterson Air Force Base, Colorado Thursday, August 2, 2018 Vol. 62 No. 31 Airman posthumously receives Medal of Honor HURLBURT FIELD, Fla. (AFNS) − As a combat controller, Tech. Sgt. John A. Chapman was trained and equipped for immediate deployment into combat operations. Trained to infiltrate in combat and austere environments, he was an experienced static line and military free fall jumper, and combat diver. By Staff Sgt. Ryan Conroy Combat control training is more than two years 24th Special Operations Wing Public Affairs long and amongst the most rigorous in the U.S. military. Only about one in ten Airmen who start the program graduate. HURLBURT FIELD, Fla. (AFNS) — The White From months of rigorous physical fitness train- House announced July 27, 2018, that Air Force ing to multiple joint schools – including military Tech. Sgt. John Chapman will be posthumously SCUBA, Army static-line and freefall, air traffic awarded the Medal of Honor Aug. 22, for his ex- control, and combat control schools – Chapman is traordinary heroism during the Battle of Takur remembered as someone who could do anything Ghar, Afghanistan, in March 2002. put in front of him. According to the Medal of Honor nomination, “One remembers two types of students — Chapman distinguished himself on the battle- the sharp ones and the really dull ones — and field through “conspicuous gallantry and intre- Chapman was in the sharp category,” said Ron pidity,” sacrificing his life to preserve those of his teammates. Childress, a former Combat Control School instructor. Making it look easy Combat Control School is one of the most Chapman enlisted in the Air Force Sept. -

The Portugese Air Force Facing Challenges Head-On Mass Migration and Financial War Air Power's Second Century

Ruivo © Jorge COMPLETE COMBAT SEARCH & RESCUE MULTI-ROLE FLEXIBILITY Edition 15, Spring / Summer 2012 Large cabin to meet demanding requirements and long range - over 900 nm demonstrated PAGE PAGE PAGE New technology, superior performance and high safety levels 6 45 55 Cost-effective through-life support and training based on operational experience agustawestland.com The Portugese Air Force Mass Migration Air Power’s Second Facing Challenges Head-On and Financial War Century: Interview with General José Pinheiro New Challenges Growing Dominance Chief of Sta , Portugese Air Force for Air Power? or Faded Glory? M-12-0055 NATO JAPCC AW101 journal advert.indd 1 10/02/2012 12:55:28 Joint Air & Space Power Conference ‘The Infl uence of Air Power upon History’ Walter Boyne is a retired U.S. Air Force Offi cer and Command pilot who has written 09th –11th 36 diff erent books on aviation. He was one of the fi rst directors of the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum and founded the bestselling aviation magazine Air&Space. October This book, from 2003, starts from the very beginning of the quest for the air, study- ing the development of Air Power philosophy and its evolution from theory to practice, through innovative thinkers’ infl uence and technological improvements that impacted not only military, but also commercial aviation, until the translation to Air and Space Power. In this pattern it off ers a comprehensive outlook of the use of Air Power to infl uence politics, not only from the military perspective, but also 2012 covering the commercial and humanitarian viewpoint. The analysis covers from the early times of balloons through the exploitation of space, through the two World Wars, the Cold War, Middle East confl icts etc., lead- ing to some interesting, controversial conclusions, departing from the generally By Walter J.Boyne accepted scenarios of Air Power.