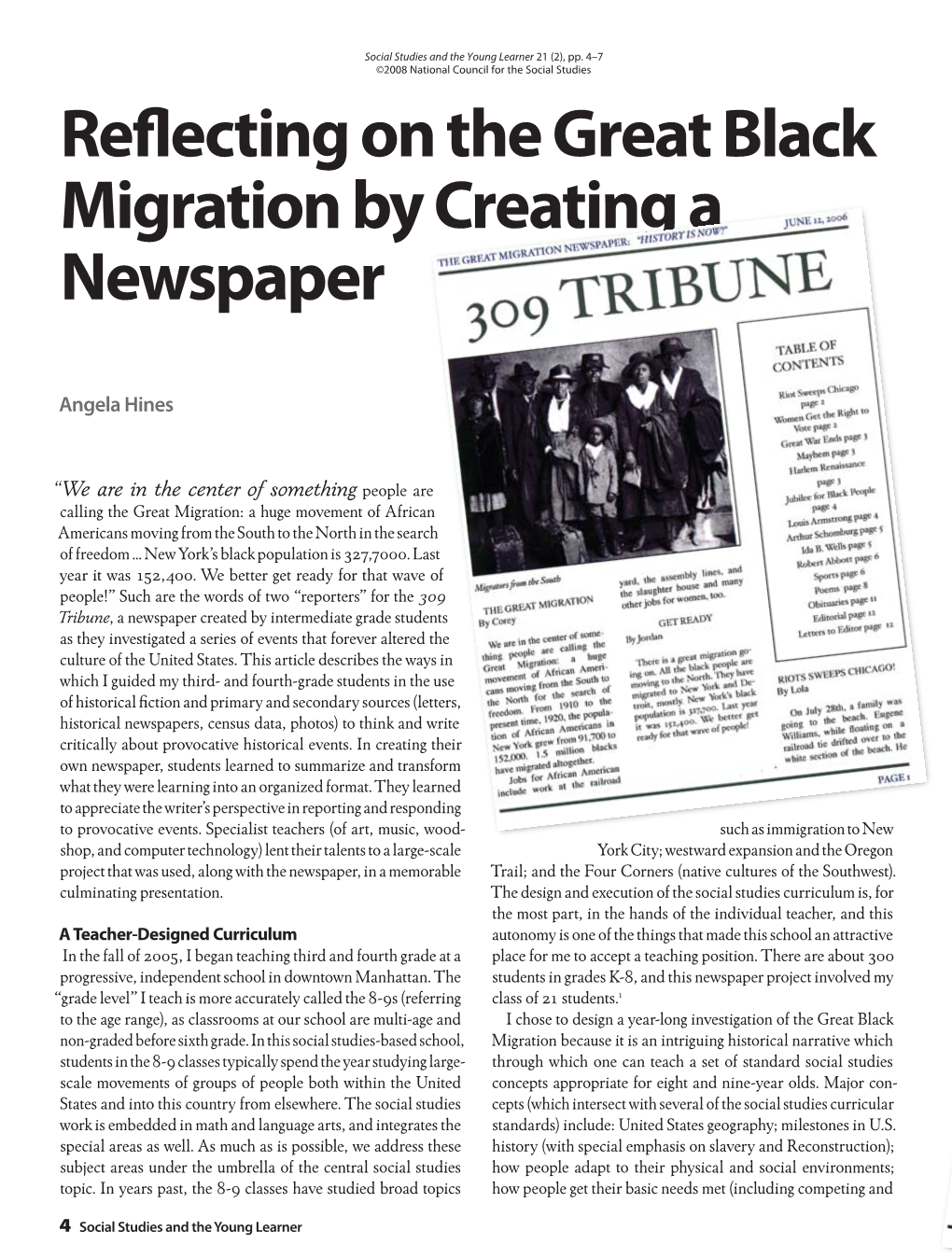

Reflecting on the Great Black Migration by Creating a Newspaper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Negro Press and the Image of Success: 1920-19391 Ronald G

the negro press and the image of success: 1920-19391 ronald g. waiters For all the talk of a "New Negro," that period between the first two world wars of this century produced many different Negroes, just some of them "new." Neither in life nor in art was there a single figure in whose image the whole race stood or fell; only in the minds of most Whites could all Blacks be lumped together. Chasms separated W. E. B. DuBois, icy, intellectual and increasingly radical, from Jesse Binga, prosperous banker, philanthropist and Roman Catholic. Both of these had little enough in common with the sharecropper, illiterate and bur dened with debt, perhaps dreaming of a North where—rumor had it—a man could make a better living and gain a margin of respect. There was Marcus Garvey, costumes and oratory fantastic, wooing the Black masses with visions of Africa and race glory while Father Divine promised them a bi-racial heaven presided over by a Black god. Yet no history of the time should leave out that apostle of occupational training and booster of business, Robert Russa Moton. And perhaps a place should be made for William S. Braithwaite, an aesthete so anonymously genteel that few of his White readers realized he was Black. These were men very different from Langston Hughes and the other Harlem poets who were finding music in their heritage while rejecting capitalistic America (whose chil dren and refugees they were). And, in this confusion of voices, who was there to speak for the broken and degraded like the pitiful old man, born in slavery ninety-two years before, paraded by a Mississippi chap ter of the American Legion in front of the national convention of 1923 with a sign identifying him as the "Champeen Chicken Thief of the Con federate Army"?2 In this cacaphony, and through these decades of alternate boom and bust, one particular voice retained a consistent message, though condi tions might prove the message itself to be inconsistent. -

The Crisis, Vol. 1, No. 2. (December, 1910)

THE CRISIS A RECORD OF THE DARKER RACES Volume One DECEMBER, 1910 Number Two Edited by W. E. BURGHARDT DU BOIS, with the co-operation of Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly Miller, VV. S. Braithwaite and M. D. Maclean. CONTENTS Along the Color Line 5 Opinion . 11 Editorial ... 16 Cartoon .... 18 By JOHN HENRY ADAMS Editorial .... 20 The Real Race Prob lem 22 By Profeaor FRANZ BOAS The Burden ... 26 Talks About Women 28 By Mn. J. E. MILHOLLAND Letters 28 What to Read . 30 PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE National Association for the Advancement of Colored People AT TWENTY VESEY STREET NEW YORK CITY ONE DOLLAR A YEAR TEN CENTS A COPY THE CRISIS ADVERTISER ONE OF THE SUREST WAYS TO SUCCEED IN LIFE IS TO TAKE A COURSE AT The Touissant Conservatory of Art and Music 253 West 134th Street NEW YORK CITY The most up-to-date and thoroughly equipped conservatory in the city. Conducted under the supervision of MME. E. TOUISSANT WELCOME The Foremost Female Artist of the Race Courses in Art Drawing, Pen and Ink Sketching, Crayon, Pastel, Water Color, Oil Painting, Designing, Cartooning, Fashion Designing, Sign Painting, Portrait Painting and Photo Enlarging in Crayon, Water Color, Pastel and Oil. Artistic Painting of Parasols, Fans, Book Marks, Pin Cushions, Lamp Shades, Curtains, Screens, Piano and Mantel Covers, Sofa Pillows, etc. Music Piano, Violin, Mandolin, Voice Culture and all Brass and Reed Instruments. TERMS REASONABLE THE CRISIS ADVERTISER THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION for the ADVANCEMENT of COLORED PEOPLE OBJECT.—The National Association COMMITTEE.—Our work is car for the Advancement of Colored People ried on under the auspices of the follow is an organization composed of men and ing General Committee, in addition to the women of all races and classes who be officers named: lieve that the present widespread increase of prejudice against colored races and •Miss Gertrude Barnum, New York. -

Strong Men, Strong MINDS

STRONG MEN, STRONG MINDS A DISCUSSION ABOUT EMPOWERING AND UPLIFTING THE BLACK COMMUNITY JOIN US at 2 pm Saturday, August 1, 2020 facebook.com/IndyRecorder Moderator: Panelist: Panelist: Panelist: Panelist: Larry Smith Kenneth Allen Keith Graves Minister Nuri Muhammad Clyde Posley Jr., Ph.D. Community Servant Chairman Indianapolis City-County Speaker, Author Senior Pastor Indianapolis Recorder Indiana Commission on the Council District 13 Community Organizer Antioch Baptist Church Newspaper Columnist Social Status of Black Males Mosque #74 Indiana’s Greatest Weekly Newspaper Preparing a conscious community today and beyond Friday, July 31, 2020 Since 1895 www.indianapolisrecorder.com 75 cents ‘Elicit a change’: protests then and now By BREANNA COOPER [email protected] Mmoja Ajabu was 19 when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. He was in the military at the time, in training in Missouri. He and the other Black soldiers in his base were Taran Richardson (left) stands relegated to a remote part of the with Kelli Marshall, who previously base and told they would be shot worked at Tindley Accelerated Schools, where Richardson gradu- if they attempted to leave as the ated from this year. Richardson white soldiers went out to “quell plans to attend Howard University the rebellion in St. Louis,” he said. in the fall to study astrophysics. (Photo provided) “I started understanding at that point what the hell was going on,” Ajabu said. Tindley grad ready NiSean Jones, founder of Black Out for Black Lives, addresses a for a new challenge See PROTESTS, A5® crowd downtown on June 19. (Photo/Tyler Fenwick) IPS MAY VOTE TO at Howard University CHANGE COURSE By TYLER FENWICK [email protected] By STAFF Indianapolis Public Schools (IPS) When Taran Richardson was in high could change course and go to e- school at Tindley Accelerated Schools, learning for all students instead of he developed an appropriate motto for giving students the option of vir- himself: #NoSleepInMySchedule. -

OBJ (Application/Pdf)

OPINIONS AND ACTIVITIES OF THE BLACK COMMUNITY DURING WORLD WAR II AS SEEN IN THE BLACK PRESS AND RELATED SOURCES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY BERNADETTE EILEEN SHEPARD DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA DECEMBER 1974 U TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. BLACKS ON THE HOME FRONT 12 War Industries and Jobs 17 III. TREATMENT OF BLACKS IN THE ARMED FORCES . 27 Enlistment and Training • 28 Incidents of Prejudices in the Armed Forces 40 CONCLUSION 44 BIBLIOGRAPHY 47 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION The first World War provided the tide of protest upon which the Black Press rose in importance and in militancy. It was largely the Black press that made Blacks fully conscious of the inconsistency between America's war aims to "make the world safe for "demo cracy" and her treatment of this minority at home. The Second World War again increased unrest, suspicion, and dissatisfaction among Blacks. lit stimulated great interest of the Black man in his press and the fact that the depression was just about over made it possible for him to translate this interest into financial support. By the outbreak of the war many Black newspapers had become economically able to send their own corres pondents overseas. In addition, the Chicago Defender; the Baltimore Afro-American and the Norfolk Journal and Guide had special correspondents who traveled from camp 3-Gunnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma (New York: Harper and Row, 1944), p. 914. 2Vishnu V. -

Download Download

W. E. B. Du Bois, F. B. Ransom, the Madam Walker Company, and Black Business Leadership in the 1930s Mark David Higbee" From the 1870s to the 1930s, the development of business en- terprise was widely seen as the one essential ingredient for Afri- can-American progress. Yet neither African-American business enterprise nor the political roles of black entrepreneurs have been adequately studied by historians. Accounts of African-American ec- onomic hardships during the Great Depression have slighted the important political debates that these hardships produced. Simi- larly, writings on W. E. B. Du Bois, the black scholar and founder of the twentieth-century civil rights protest tradition, have ne- glected his distinctive vision of African-American business enter- prise. Consequently, a little known 1937-1938 dispute between Du Bois and Freeman B. Ransom, an African-American businessman and Indianapolis community leader, demands attention. Ransom and Du Bois viewed the proper aims of business enterprise in rad- ically opposing ways. The Ransom-Du Bois dispute provides an op- portunity to examine the differing ways these two leaders approached the problems of the Depression as well as how African Americans reconsidered older ideas of black business enterprise and political leadership. Studying the 1930s is acutely important because during that decade faith in business as the basis for Afri- can-American leadership was supplanted by political and labor strategies. * Mark Higbee is completing a dissertation on W.E.B. Du Bois at Columbia University, New York. He thanks the following people for their comments on vari- ous drafts of this essay: Barbara Bair, Eric Bates, Martha Biondi, Jonathan Bir- enbaum, Elizabeth Blackmar, Eric Foner, Wilma Gibbs, Sarah Henry, Kate Levin, Judith Stein, the members of Col'umbia University's U.S. -

The Crisis (Brookings Papers on Economic

12178-04a_Greenspan-rev2.qxd 8/11/10 12:14 PM Page 201 ALAN GREENSPAN Greenspan Associates The Crisis ABSTRACT Geopolitical changes following the end of the Cold War induced a worldwide decline in real long-term interest rates that, in turn, pro- duced home price bubbles across more than a dozen countries. However, it was the heavy securitization of the U.S. subprime mortgage market from 2003 to 2006 that spawned the toxic assets that triggered the disruptive collapse of the global bubble in 2007–08. Private counterparty risk management and offi- cial regulation failed to set levels of capital and liquidity that would have thwarted financial contagion and assuaged the impact of the crisis. This woe- ful record has energized regulatory reform but also suggests that regulations that require a forecast are likely to fail. Instead, the primary imperative has to be increased regulatory capital, liquidity, and collateral requirements for banks and shadow banks alike. Policies that presume that some institutions are “too big to fail” cannot be allowed to stand. Finally, a range of evidence suggests that monetary policy was not the source of the bubble. I. Preamble The bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 precipitated what, in retrospect, is likely to be judged the most virulent global financial crisis ever. To be sure, the contraction in economic activity that followed in its wake has fallen far short of the depression of the 1930s. But a precedent for the virtual withdrawal, on so global a scale, of private short-term credit, the leading edge of financial crisis, is not readily evident in our financial history. -

The Role of the Black Press During the "Great

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 270 799 CS 209 883 AUTHOR Jones, Felecia G. TITLE The Role of the Black Press during the "Great Migration." PUB DATE Aug 86 NOTE 26p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (69th, Norman, OK, August 3-6, 1986). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) -- Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Black Employment; *Black History; Comparative Analysis; Content Analysis; Economic Opportunities; Employment Opportunities; Journalism; Migration; *Migration Patterns; *Newspapers; *Press Opinion; Social Change; Social History; Socioeconomic Influences; United States History IDENTIFIERS *Black Migration; Black Press; *Journalism History ABSTRACT Between the years of 1916 and 1918 southern blacks began populating the urban centers of the north in a movement known as the "Great Migration." This movement was significant to the development of the black press, for it was during this period that the black press became a protest organ and rose to its greatest level of prominence and influence. Some newspapers encouraged the migration while others discouraged it. Considered to be thenewspaper that revolutionized black journalism, the Chicago "Defends:"ran cartoons satirizing the pitiful conditions of blacks in the South andsuccess stories were printed of southern blacks who had been successful in the North. It also counseled migrants on dress, sanitation, and behavior, and initiated fund drives for needy families. The conservative principles of Washington, D.C., were reflected in the content of the Norfolk/Tidewater "Journal and Guide." Its stance against migration was reflected in a series of articles, cartoons, and editorials that stressed the poor living conditions, racial discrimination, and false job hopes that existed in the North. -

NEGRO PUBLICATIONS. Newspapers. When Federal Troops

NEGRO PUBLICATIONS. Newspapers. When federal troops marched into Oxford, Miss., following the desegrega tion of the University of Mississippi in September 1962, the circulation of Negro newspapers across the country reached an all-year high. As the tension subsided and it became apparent that James H. Meredith, the first known Negro ever to be enrolled by "Ole Miss,” would be allowed to remain, the aggregate circulation of Negro newspapers dwindled again to an approximate 1.5 million. Since the end of World War II, when the nation’s Negro newspapers began a general decline in both number and cir culation, racial crises have been the principal spur to periodic —and usually temporary—circulation increases. The editor of a Detroit Negro weekly equated the survival of the Negro press with the prevailing degree of Jim Crow. "If racial discrimination and enforced segregation were ended tomor row,” he suggested, "the Negro press would all but disappear from the national scene.” While this statement is a deliberate oversimplification of the situation, it is borne out, to some extent, by the recent history of the Negro press. In 1948, six years before the Supreme Court desegregation decision, there were some 202 Negro newspapers with a total circulation of 3 million. But in 1962, according to the annual report of the Lincoln (Mo.) University School of Journalism, the number of Negro news papers—daily, weekly, semiweekly, and biweekly—had shrunk to 133, with a gross circulation of just over half the 1948 figure. The Pittsburgh Courier, which in 1948 boasted a national weekly circulation of 300,000, now sells about 86,000 copies in its various editions. -

The Crisis, October 1929

A RECORD OF-·THE DARKER RAC£5 A MESSAGE FROM TAGORE LIKE the proverbial Green Bay Tree, the SOUTHERN AID SOCIETY OF VA., INC., is spreading its branches over the state of New Jersey. Thriving districts and agencies have been established at Newark, Trenton, Camden, Paterson, the Oranges, Montclair, Atlantic City and . " Asbury Park. tt: s>ii') ,e Danville, Va., Bldg. 212-14-16 N. Ridge St. The wide awake race citizens in these centers are giving this company a liberal share of their insurance patronage, and thus are the recipients of the two-fold service which this company offers its policyholders; namely, personal protection when disabled by sickness or accident, and a death claim after death, also dignified and profitable em ployment to worthy race men and women, which means an elevation of race people in the economic scale of life. Without this superior insurance contract which, for one small premium provides protection against disability and death, and which also makes it possible for worthy race boys and girls to have employment, your insurance needs have not been met. --------------��------------- Southern Aid Society of Virginia,Inc. Home Office: 525-7-9 N. 2nd Street, Richmond, Va. Operating in Virginia, District of Columbia and New Jersey Life on Cotton Plantation rro , God, Bri1tg Back Our Zeke" HALLELUJAH King Vidor' s All Talking Picture Proditced by METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER PICTURE CORPORATION THE STORY: Chick drifted into a lii� of sin, made efforts to climb out and lost, as women do sometimes. Zeke followed Chick into the depths, struggled to escape, comn1itted murder, but finally won, returning home a chastened man. -

Cooperative Ownership in the Struggle for African American Economic Empowerment

Cooperative Ownership in the Struggle for African American Economic Empowerment Jessica Gordon Nembhard, Ph.D. African American Studies, and The Democracy Collaborative University of Maryland, College Park 1228 Tawes Hall College Park, MD 20742 [email protected] 301-405-6220 September 2004 To appear in Humanity and Society Vol. 28, No. 3 August 2004. Reflection Statement: I am a political economist. I specialize in “democratic community economics.” I study people-centered local economic development that is community-based and controlled, collaborative, democratically (or at least broadly) owned and governed through a variety of structures. These structures include worker, producer and consumer owned cooperatives; community land trusts; democratic ESOPs (Employee Stock Ownership Programs) and other forms of worker ownership and self-management. Also included are collective not-for-profit organizations; municipally owned enterprises; community development financial institutions and credit unions; community- controlled community development corporations, and community-controlled development planning. My analysis includes the theoretical and applied study of how and why such alternative structures are economically viable and sustainable, the public policies that are supportive of such development, and ways to document and measure their traditional and non-traditional economic, social and political outcomes and impacts. Much of my research on alternative democratic community-based economic development focuses on how to bring -

Dreasjon Reed's Family Sues City, IMPD

A Celebration Celebrate of Freedom JuneteenthEmancipation Indiana’s Greatest Weekly Newspaper Preparing a conscious community today and beyond Friday, June 19, 2020 Since 1895 www.indianapolisrecorder.com 75 cents ‘Defund’ police is a lofty demand, but not totally unfeasible in Indy By TYLER FENWICK [email protected] When protesters fi rst hit the streets in Indianapolis in late May and early June, their chants were the familiar ones. “No justice, no peace!” Some people want to see police de- “If we don’t get it, shut it down!” partments abolished so public safety “What do we want? Justice! When do can be reinvented from ground up. we want it? Now!” Others want to see spending on pub- And then came a new slogan, one that wasn’t diffi cult to memorize: “Defund See DEFUND, A3 ® the police!” Hogsett announces partnership to Dreasjon Reed’s mother, Demetree Wynn, walks with Elder Lionel Rush of Greater Anointing Fellowship Church before a press conference June 2 near Michigan Road and 62nd Street. ‘chart new path’ for public safety (Photo/Tyler Fenwick) By BREANNA COOPER • Broaden sets of data used to defi ne [email protected] public safety. Hogsett gave the ex- By TYLER FENWICK [email protected] ample of using high school graduation rates as a potential determinant of Dreasjon Reed’s public safety. The city of Indianapolis will partner • Data analysts will track and moni- with the Criminal Justice Lab at the tor those public safety measures, and New York University School of Law to public safety agencies will be held to a family sues city, IMPD create a new approach to public safety standard defi ned by the community. -

The Crisis, Vol. 7, No. 2 (December, 1913)

CHRISTMAS 1913 TEN CENTS A COPY Do You Like THE CRISIS? Are you willing to help in our cam paign for a circulation of 50,000 ? Christmas Greetings of THECRISIS which will come to you monthly during the new year as a gift from If so, send for one or more of these beautiful Xmas cards, printed in three colors on cards with gilded and beveled edges, together with envelopes. Sent free for the asking. THE CRISIS, 26 Vesey Street, NEW YORK THE CRISIS A RECORD OF THE DARKER RACES PUBLISHED BY THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, AT 26 VESEY STREET, NEW YORK CITY Conducted by W. E. BURGHARDT DU BOIS AUGUSTUS GRANVILLE DILL, Business Manager Contents for December, 1913 PICTURES COVER PICTURE: Madonna and the Child. Copyright photograph from life by W. L. Brockman. (Orders taken by THE CRISIS) "MAMMY'S LI'L BABY BOY." Page Photograph from life by Grace Moseley 67 THE NATIONAL EMANCIPATION EXPOSITION: THE TEMPLE OF BEAUTY IN THE GREAT COURT OF FREEDOM 78 THE HISTORICAL PAGEANT OF THE NEGRO RACE: FORTY MAIDENS DANCE BEFORE THE ENTHRONED PHARAOH RA, THE NEGRO 79 ARTICLES THE MAN THEY DIDN'T KNOW. A Story. By James D. Corrothers. Part 1 85 CHILDREN OF THE SUN. A Poem. By Fenton Johnson 91 DEPARTMENTS ALONG THE COLOR LINE 59 MEN OF THE MONTH 65 OPINION 68 EDITORIAL 80 NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE 88 THE BURDEN 92 TEN CENTS A COPY; ONE DOLLAR A YEAR FOREIGN SUBSCRIPTIONS TWENTY-FIVE CENTS EXTRA RENEWALS: When a subscription blank is attached to this page a renewal of your subscription is desired.