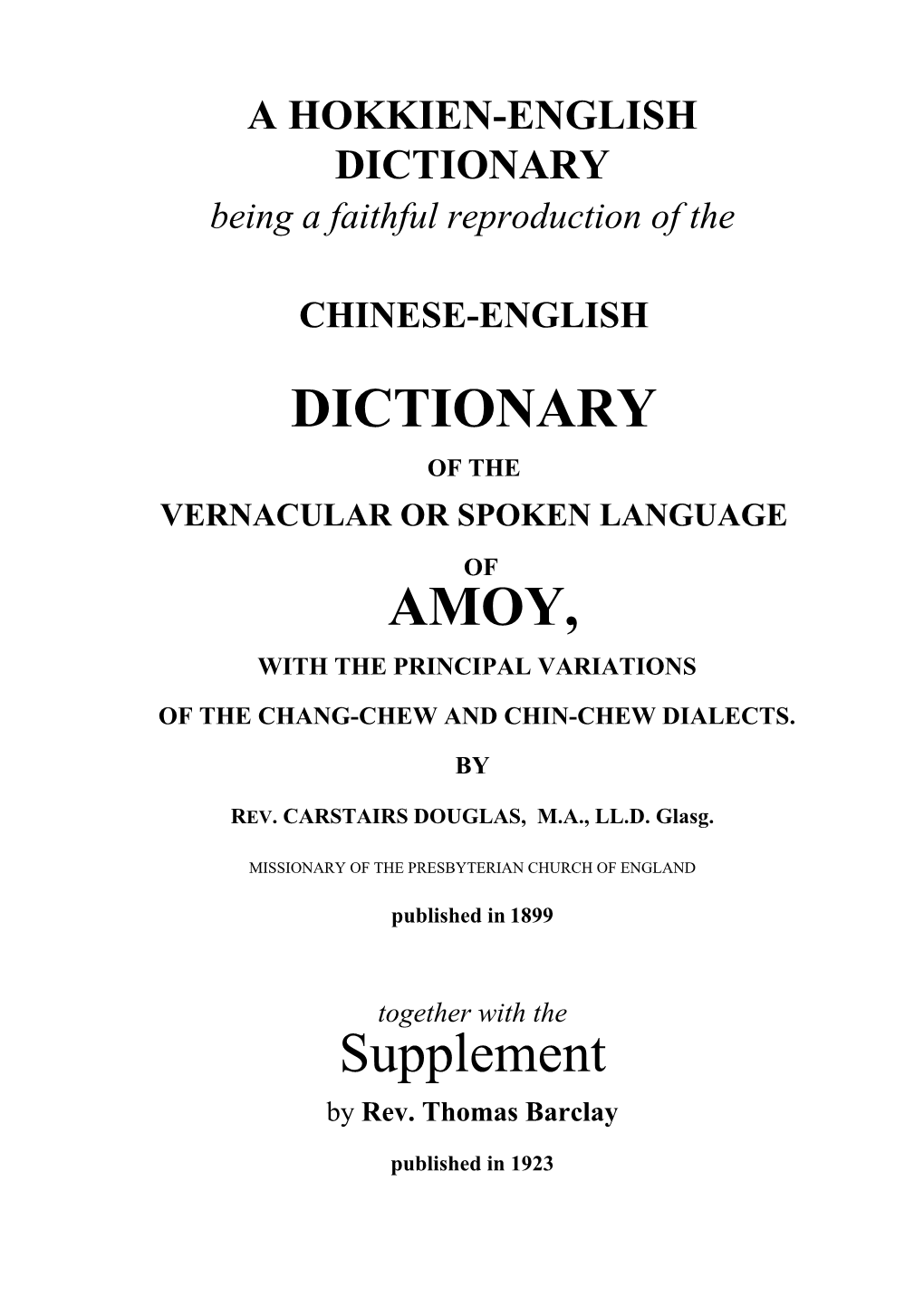

DICTIONARY AMOY, Supplement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Missionary Advocate

MISSIONARY ADVOCATE. HIS DOMINION SHALL BE FROM SEA EVEN TO SEA, AND FROM THE RIVER EVEN TO THE ENDS OF THE EARTH. VOLUME XL NEW-YORK, JANUARY, 1856. NUMBER 10. THB “ ROTAL PALACE ” AT OFIN. IN THE IJEBU COUNTRY. AFRICA. in distant lands, and direct their attention to the little JAPAN. gardens which here and there have been fenced in from A it a rriva l at San Francisco, of a gentleman who Above is presented a sketch taken in the Ijebu country, the wilderness. But it will not do always to dwell on went out from that port to Japan on a trading expedi an African district on the Bight of Benin, lying to the these, lest in what haB been done we forget all that re tion, affords the following information:— southwest of Egba, where the missionaries arc at work. mains to be done. We must betimes look from these In Egba they have several stations—at Abbeokuta, and pleasant spots to the dreary wastes beyond, that, re The religion of this country is as strange as the people Ibadan, and Ijaye, &e.; but into Ijebu they are only be themselves. Our short stay here has not afforded us minded of the misery of millions to whom as yet no much opportunity to become conversant with all their ginning to find entrance. It is much to be desired that missionaries have been sen’t, we may redouble our vocations and religious opinions. So far as I know of the Gospel of Christ should be introduced among the efforts, and haste to the help of those who are perishing them I will write you. -

Mission and Revolution in Central Asia

Mission and Revolution in Central Asia The MCCS Mission Work in Eastern Turkestan 1892-1938 by John Hultvall A translation by Birgitta Åhman into English of the original book, Mission och revolution i Centralasien, published by Gummessons, Stockholm, 1981, in the series STUDIA MISSIONALIA UPSALIENSIA XXXV. TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword by Ambassador Gunnar Jarring Preface by the author I. Eastern Turkestan – An Isolated Country and Yet a Meeting Place 1. A Geographical Survey 2. Different Ethnic Groups 3. Scenes from Everyday Life 4. A Brief Historical Survey 5. Religious Concepts among the Chinese Rulers 6. The Religion of the Masses 7. Eastern Turkestan Church History II. Exploring the Mission Field 1892 -1900. From N. F. Höijer to the Boxer Uprising 1. An Un-known Mission Field 2. Pioneers 3. Diffident Missionary Endeavours 4. Sven Hedin – a Critic and a Friend 5. Real Adversities III. The Foundation 1901 – 1912. From the Boxer Uprising to the Birth of the Republic. 1. New Missionaries Keep Coming to the Field in a Constant Stream 2. Mission Medical Care is Organized 3. The Chinese Branch of the Mission Develops 4. The Bible Dispute 5. Starting Children’s Homes 6. The Republican Frenzy Reaches Kashgar 7. The Results of the Founding Years IV. Stabilization 1912 – 1923. From Sjöholm’s Inspection Tour to the First Persecution. 1. The Inspection of 1913 2. The Eastern Turkestan Conference 3. The Schools – an Attempt to Reach Young People 4. The Literary Work Transgressing all Frontiers 5. The Church is Taking Roots 6. The First World War – Seen from a Distance 7. -

Territorialising Colonial Environments: a Comparison of Colonial Sciences on Land Demarcation in Japanese Taiwan and British Malaya

Durham E-Theses Territorialising Colonial Environments: A Comparison of Colonial Sciences on Land Demarcation in Japanese Taiwan and British Malaya YEH, ER-JIAN How to cite: YEH, ER-JIAN (2011) Territorialising Colonial Environments: A Comparison of Colonial Sciences on Land Demarcation in Japanese Taiwan and British Malaya, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3199/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Territorialising Colonial Environments: A Comparison of Colonial Sciences on Land Demarcation in Japanese Taiwan and British Malaya ER-JIAN YEH Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Geography Durham University United Kingdom September 2011 Supervised by Doctor Michael A. Crang, Divya Tolia-Kelly, and Cheryl McEwan i ABSTRACT The thesis seeks to establish how far, and in what ways, colonial science articulates a distinctive mode of environmental conceptions and governance. -

Pan-Sinitic Object Marking: Morphology and Syntax*

Breaking Down the Barriers, 785-816 2013-1-050-037-000234-1 Pan-Sinitic Object Marking: * Morphology and Syntax Hilary Chappell (曹茜蕾) EHESS In Chinese languages, when a direct object occurs in a non-canonical position preceding the main verb, this SOV structure can be morphologically marked by a preposition whose source comes largely from verbs or deverbal prepositions. For example, markers such as kā 共 in Southern Min are ultimately derived from the verb ‘to accompany’, pau11 幫 in many Huizhou and Wu dialects is derived from the verb ‘to help’ and bǎ 把 from the verb ‘to hold’ in standard Mandarin and the Jin dialects. In general, these markers are used to highlight an explicit change of state affecting a referential object, located in this preverbal position. This analysis sets out to address the issue of diversity in such object-marking constructions in order to examine the question of whether areal patterns exist within Sinitic languages on the basis of the main lexical fields of the object markers, if not the construction types. The possibility of establishing four major linguistic zones in China is thus explored with respect to grammaticalization pathways. Key words: typology, grammaticalization, object marking, disposal constructions, linguistic zones 1. Background to the issue In the case of transitive verbs, it is uncontroversial to state that a common word order in Sinitic languages is for direct objects to follow the main verb without any overt morphological marking: * This is a “cross-straits” paper as earlier versions were presented in turn at both the Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, during the joint 14th Annual Conference of the International Association of Chinese Linguistics and 10th International Symposium on Chinese Languages and Linguistics, held in Taipei in May 25-29, 2006 and also at an invited seminar at the Institute of Linguistics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing on 23rd October 2006. -

Sketch of the History of Protestant Missions in China

CONTENTS . E = AKING VEN S TH E POCH M E T , ERIO D O F R ARA ION P P EP T , PERIO D O F N RANCE E T , PERIO D O F OCCUPATION O F CO AST E PROV INC S, V P RIO D F = O RA ION AND O F O CCU . E O CO PE T PATION F NLAND ROV INC S 30 O I P E , I PERIO D O F E! TENSION AND V ELO M N 34 V . DE P E T , NOTE. This b o o klet has b een prepared primarily fo r the u se o f Mie sio nary Classes stu dying u nder the direc tio n o f the Edu c atio nal D epartm ent o f the Stu dent V o lu nteer Mo vem ent fo r F o reign Mi i n It m er r f intere t t m n thers ss o s. ay h o wev p o ve o s o a y o ’ i n r n f r in e iz ati n wh o are pray ng a d wo ki g o Ch a s evang l o . SKETCH O F THE HISTORY O F PROTES I TANT MISSIONS IN CH NA. c h flakin ents . l. The Epo g Ev s c um Clo ed . At the opening of this century China was as effectually closed to Protestant missionary effort c ou ld it as human power close , nor did there seem to be any immediate probability of a change favorable r i to the int oduct on of Christianity . -

The Presbyterian Church in Taiwan and the Advocacy of Local Autonomy

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 92 January, 1999 The Presbyterian Church in Taiwan and the Advocacy of Local Autonomy by Christine Louise Lin Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series edited by Victor H. Mair. The purpose of the series is to make available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including Romanized Modern Standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino-Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. The only style-sheet we honor is that of consistency. Where possible, we prefer the usages of the Journal of Asian Studies. Sinographs (hanzi, also called tetragraphs [fangkuaizi]) and other unusual symbols should be kept to an absolute minimum. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. -

Catalogue of the Officers and Alumni of Rutgers College

* o * ^^ •^^^^- ^^-9^- A <i " c ^ <^ - « O .^1 * "^ ^ "^ • Ellis'* -^^ "^ -vMW* ^ • * ^ ^^ > ->^ O^ ' o N o . .v^ .>^«fiv.. ^^^^^^^ _.^y^..^ ^^ -*v^^ ^'\°mf-\^^'\ \^° /\. l^^.-" ,-^^\ ^^: -ov- : ^^--^ .-^^^ \ -^ «7 ^^ =! ' -^^ "'T^s- ,**^ .'i^ %"'*-< ,*^ .0 : "SOL JUSTITI/E ET OCCIDENTEM ILLUSTRA." CATALOGUE ^^^^ OFFICERS AND ALUMNI RUTGEES COLLEGE (ORIGINALLY QUEEN'S COLLEGE) IlSr NEW BRUJSrSWICK, N. J., 1770 TO 1885. coup\\.to ax \R\l\nG> S-^ROUG upsoh. k.\a., C\.NSS OP \88\, UBR^P,\^H 0? THP. COLLtGit. TRENTON, N. J. John L. Murphy, Printer. 1885. w <cr <<«^ U]) ^-] ?i 4i6o?' ABBREVIATIONS L. S. Law School. M. Medical Department. M. C. Medical College. N. B. New Brunswick, N. J. Surgeons. P. and S. Physicians and America. R. C. A. Reformed Church in R. D. Reformed, Dutch. S.T.P. Professor of Sacred Theology. U. P. United Presbyterian. U. S. N. United States Navy. w. c. Without charge. NOTES. the decease of the person. 1. The asterisk (*) indicates indicates that the address has not been 2. The interrogation (?) verified. conferred by the College, which has 3. The list of Honorary Degrees omitted from usually appeared in this series of Catalogues, is has not been this edition, as the necessary correspondence this pamphlet. completed at the time set for the publication of COMPILER'S NOTICE. respecting every After diligent efforts to secure full information knowledge in many name in this Catalogue, the compiler finds his calls upon every one inter- cases still imperfect. He most earnestly correcting any errors, by ested, to aid in completing the record, and in the Librarian sending specific notice of the same, at an early day, to Catalogue may be as of the College, so that the next issue of the accurate as possible. -

The Lexical Influence of the Bible Translation on Church on Language in Taiwan Is Rather Little

Dong Hwa Journal of Humanistic Studies,No.4 July 2002,pp.331-400 College of Humanities and Social Sciences National Dong Hwa University Dong Hwa Journal of Humanistic Studies.No.4 including the Amoy dialect and the liturgical register in the lexicon are decreasing. This implies that the religious impact from the Prebysterian The Lexical Influence of the Bible Translation on Church on language in Taiwan is rather little. This also implies that Taiwanese Novel Writing, 1916-1998: Taiwanese identity of the language and culture has been emerging by A Computer-Assisted Corpus Analysis making distinction from the Amoy in China. Chin-an Li* Keywords: church register, Taiwanese novel, corpus analysis, Taiwanese Romanization, Bible translation Abstract In 1916, Rev. Thomas Barclay (1874-1935) published the New Testament Taiwanese Romanization (Peh-oe-ji) and then the Old Testament in 1933. This version of the Bible has been used in Taiwanese Presbyterian Church in Taiwan as well as overseas. The so-called "Taiwanese Han-ji edition" of the Bible was published late to 1996 with replacement of the Romanization only. The lexis and syntax remain the same. Many lexical items in the Bible translation are the Amoy dialect or liturgical register which are not familiar to the present-day Taiwanese. Using computer-aided segmentation supplemented by manual segmentation, I found 112,964 word tokens with 12,941 word types in this corpus. I also collected a second corpus with 92,539 word tokens and 12,969 word types consisting of the short stories of Tan5 Lui5 and Tan5 Beng5-jin5 written in the 1990's. -

LANGUAGE CONTACT and AREAL DIFFUSION in SINITIC LANGUAGES (Pre-Publication Version)

LANGUAGE CONTACT AND AREAL DIFFUSION IN SINITIC LANGUAGES (pre-publication version) Hilary Chappell This analysis includes a description of language contact phenomena such as stratification, hybridization and convergence for Sinitic languages. It also presents typologically unusual grammatical features for Sinitic such as double patient constructions, negative existential constructions and agentive adversative passives, while tracing the development of complementizers and diminutives and demarcating the extent of their use across Sinitic and the Sinospheric zone. Both these kinds of data are then used to explore the issue of the adequacy of the comparative method to model linguistic relationships inside and outside of the Sinitic family. It is argued that any adequate explanation of language family formation and development needs to take into account these different kinds of evidence (or counter-evidence) in modeling genetic relationships. In §1 the application of the comparative method to Chinese is reviewed, closely followed by a brief description of the typological features of Sinitic languages in §2. The main body of this chapter is contained in two final sections: §3 discusses three main outcomes of language contact, while §4 investigates morphosyntactic features that evoke either the North-South divide in Sinitic or areal diffusion of certain features in Southeast and East Asia as opposed to grammaticalization pathways that are crosslinguistically common.i 1. The comparative method and reconstruction of Sinitic In Chinese historical -

Exploring the Relationship Between Urban Transportation Energy Consumption and Transition of Settlement Morphology: a Case Study on Xiamen Island, Chinaq

Habitat International xxx (2012) 1e10 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Habitat International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/habitatint Exploring the relationship between urban transportation energy consumption and transition of settlement morphology: A case study on Xiamen Island, Chinaq Jian Zhou a,b,1, Jianyi Lin a,b,2, Shenghui Cui a,b,*, Quanyi Qiu a,b,3, Qianjun Zhao a,c,4 a Key Lab of Urban Environment and Health, Institute of Urban Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 1799 Jimei Road, Xiamen 361021, China b Xiamen Key Lab of Urban Metabolism, Xiamen 361021, China c Institute of Remote Sensing Applications, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China abstract Keywords: It is important to understand the settlement morphology and its transition process in the rapid Urban transport urbanization cities of developing countries. It is equally important to learn about the relationships Energy consumption between transport energy consumption and the transition of settlement morphology and its underlying Settlement morphology processes. Finally, if the existing transportation technologies are already adequately meeting the envi- Urbanization Xiamen Island ronmental challenges of that sector then urban policies can serve as a guide to the transition of settle- ment morphology, especially for developing countries. Through the application of an integrated land use and transportation modeling system, TRANUS, the paper demonstrates that this transition will bring great changes to the urban spatial distribution of population, jobs and land use, and to residents’ travel patterns, thus resulting in different transportation energy consumption and CO2 emission levels, but that these changes can be managed through appropriate public policies. -

"Tho Peking System of Ortography" for the Chinese Language by G

MÉLANGES. On the extended use of "Tho Peking system of ortography" for the Chinese language BY G. SCHLEGEL. Under this title, the late lamented W. F. MAYERS, one of the best sinologues England can boast of, broke a lance against the abuse of the Peking system of ortography which then already (in 1867) became threatening. Nearly 30 years have since elapsed and, we are sorry to say, this abuse has thriven like an obnoxious weed, and menaces to overwhelm and smother entirely the standard pronunciation expressed in the Imperial Dictionary of (or Chang-lasi, as the Pekinese nowadays pronounce) by means of fixed syllabic and tonic symbols. As a whole generation has passed by since our friend wrote this article, and as the younger generation of sinologues does not seem to study the works of their predecessors, and gets as infatuated, (since Peking has been opened) with the bad, half Manchurian, pronunciation, as the Peking Chinese themselves, we deem it of 500 the highest importance to reproduce this article as the best anti- dote against the abuse of the Peking Colloquial dialect for the transcription, not only of the Chinese characters, but also of Chinese proper names, known in Europe and in europeau books on China, only in their standard pronunciation. None of the elder Sinologues, Morrison, Medhurst, Bridgman, Mayers, Stanislas Julien, R6niusat, Gaubil, only to name some of the most renowned, who have been living either in Canton, Bata- via, Peking, Amoy or Europe, have used for the transcription of Chinese characters and names the local brogue of the place where they where living and studying; all of them have used the st,(tiida??d p-?°o??nnciat,io7zin their transcriptions, and we do not see why the present generation should adopt local brogue of Peking as the standard pronunciation for the whole Chinese language. -

Donald J. Bruggink's Contribution to Reformed Church in America Historiography

Donald J. Bruggink's Contribution to Reformed Church in America Historiography Elton J. Bruins Just as Edward Tanjore Corwin was the principal historian of the Reformed Church in America (RCA) during the nineteenth century, Donald J. Bruggink is its principal historian in the twentieth century. Corwin made his contribution by producing four editions of the Manual of the Reformed Church in America,1 a mother lode of Reformed Church history, and A Digest of Constitutional and Synodical Legislation of the Reformed Church in America,2 an invaluable source on the work of the General Synod. Bruggink made his noteworthy contribution by founding and editing the Historical Series of the RCA and bringing forth thirty volumes between 1967 and 1999.3 The impact of Corwin's work can be readily attested to; we must now take note of the impact and success of Bruggink's prodigious labors as general editor of the series which have contributed so much to a better understanding of many segments of RCA history. When at the first meeting of the newly constituted Commission on History (COH) in 1967, Donald suggested the publication of RCA monographs, prospects of success were not good. The denomination had enjoyed a well 1 4 celebrated 300 h anniversary in 1928 at the height of good times in the RCA and the USA, but the Great Depression that followed proved to be rocky ground for the seeds of future historical work. Edgar F. Romig produced The Tercentenary Year, 5 a full record of the events that took place in 1928 to recognize the organization of the first Dutch Reformed Church on the Island of Manhattan in 1628.