Master Thesis Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Imperialism in Books from the “Third Reich”

Empire and National Character: British Imperialism in Books from the “Third Reich” Victoria Jane Stiles, MA, MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2015 Abstract This thesis examines the variety of representations and rhetorical deployments of the theme of British Imperialism within books published in the “Third Reich”. The thesis considers these books not only as vehicles for particular ideas and arguments but also as consumer objects and therefore as the product of a series of compromises between the needs of a host of actors, both official and commercial. It further traces the origins of the component parts of these texts via the history of reuse of images and extracts and by identifying earlier examples of particular tropes of “Englishness” and the British Empire. British imperial history was a rich source of material for National Socialist writers and educators to draw on and lent itself to a wide variety of arguments. Britain could be, in turns, a symbol of “Nordic” strength, a civilisation in decline, a natural ally and protector of Germany, or a weak, corrupt, outdated entity, controlled by Germany’s supposed enemies. Drawing on a long tradition of comparing European colonial records, the British Empire was also used as a benchmark for Germany’s former imperial achievements, particularly in moral arguments regarding the treatment of indigenous populations. Through its focus on books, which were less ephemeral than media such as newspaper and magazine articles, radio broadcasts or newsreels, the thesis demonstrates how newer writings sought to recontextualise older material in the light of changing circumstances. -

World War II at Sea This Page Intentionally Left Blank World War II at Sea

World War II at Sea This page intentionally left blank World War II at Sea AN ENCYCLOPEDIA Volume I: A–K Dr. Spencer C. Tucker Editor Dr. Paul G. Pierpaoli Jr. Associate Editor Dr. Eric W. Osborne Assistant Editor Vincent P. O’Hara Assistant Editor Copyright 2012 by ABC-CLIO, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data World War II at sea : an encyclopedia / Spencer C. Tucker. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-59884-457-3 (hardcopy : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-59884-458-0 (ebook) 1. World War, 1939–1945—Naval operations— Encyclopedias. I. Tucker, Spencer, 1937– II. Title: World War Two at sea. D770.W66 2011 940.54'503—dc23 2011042142 ISBN: 978-1-59884-457-3 EISBN: 978-1-59884-458-0 15 14 13 12 11 1 2 3 4 5 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit www.abc-clio.com for details. ABC-CLIO, LLC 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper Manufactured in the United States of America To Malcolm “Kip” Muir Jr., scholar, gifted teacher, and friend. This page intentionally left blank Contents About the Editor ix Editorial Advisory Board xi List of Entries xiii Preface xxiii Overview xxv Entries A–Z 1 Chronology of Principal Events of World War II at Sea 823 Glossary of World War II Naval Terms 831 Bibliography 839 List of Editors and Contributors 865 Categorical Index 877 Index 889 vii This page intentionally left blank About the Editor Spencer C. -

Otto Schniewind Testimony University of North Dakota

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Elwyn B. Robinson Department of Special Nuremberg Transcripts Collections 5-25-1948 High Command Case: Otto Schniewind Testimony University of North Dakota Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/nuremburg-transcripts Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation University of North Dakota, "High Command Case: Otto Schniewind Testimony" (1948). Nuremberg Transcripts. 16. https://commons.und.edu/nuremburg-transcripts/16 This Court Document is brought to you for free and open access by the Elwyn B. Robinson Department of Special Collections at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nuremberg Transcripts by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 25 May–A–MW–17–2–Gallagher (Int.Evand) COURT V, CASE XII THE PRESIDENT: You may have the same privileges and rights with respect to the documents that have been heretofore indicated. DR. FRITSCH: I merely have one request, Your Honor. In my opening statement I made a motion to strike Counts I and IV of the Indictment. I would now like to ask the Tribunal to rule on this motion. THE PRESIDENT: If you desire a ruling on that motion at this time, inasmuch as the testimony is now in,the [sic] motion will be overruled, because that is one of the essential questions that will have to be determined when the opinion is written. If there is no proof of these, why, of course, then those Counts have not been substantiated, but at this time the motion will be overruled. -

Timeline April 1940

TIMELINE APRIL 1940 There are varying opinions as to when the Phoney War came to an end. Some say it was in April 1940 with the invasion of Norway and the first really significant and direct engagement on land between Ger- man and British forces. Others say that it was in May with the invasion of the low countries and France, and, of course, Dunkirk. Wherever you stand on this point there can be no doubt that the battle for Norway marked the point of no return – any slim hopes of securing a peace settlement were effectively blown sky high. April 1940 is ALL about the battle for Norway, and I make no apologies for the fact that I am going to talk mostly about that as we work through our timeline for the month. I’m going to start by clarifying the status of the Scandinavian countries in the run-up to the battle – and by that I mean Denmark, Norway and Sweden, leaving Finland to one side for the moment - and by briefly taking you back to events that we have already covered as they set the scene, or perhaps lit the fuse, for what was to come. SCANDINAVIA 1939 At the outbreak of war all three of these Scandinavian countries were neutral, and it would have served German strategic interests for all of them to have remained neutral throughout the war. But this attitude changed in the Spring of 1940 largely as a result of actual or feared allied actions to either draw the Scandinavian countries into the war, or to gain control of Scandinavian territory. -

JFQ 11 ▼JFQ FORUM Become Customer-Oriented Purveyors of Narrow NOTES Capabilities Rather Than Combat-Oriented Or- 1 Ganizations with a Broad Focus and an Under- U.S

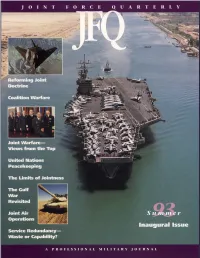

Warfare today is a thing of swift movement—of rapid concentrations. It requires the building up of enormous fire power against successive objectives with breathtaking speed. It is not a game for the unimaginative plodder. ...the truly great leader overcomes all difficulties, and campaigns and battles are nothing but a long series of difficulties to be overcome. — General George C. Marshall Fort Benning, Georgia September 18, 1941 Inaugural Issue JFQ CONTENTS A Word from the Chairman 4 by Colin L. Powell Introducing the Inaugural Issue 6 by the Editor-in-Chief JFQ FORUM JFQ Inaugural Issue The Services and Joint Warfare: 7 Four Views from the Top Projecting Strategic Land Combat Power 8 by Gordon R. Sullivan The Wave of the Future 13 by Frank B. Kelso II Complementary Capabilities from the Sea 17 by Carl E. Mundy, Jr. Ideas Count by Merrill A. McPeak JOINT FORCE QUARTERLY 22 JFQ Reforming Joint Doctrine Coalition Warfare What’s Ahead for the Armed Forces? by David E. Jeremiah Joint Warfare— Views from the Top 25 United Nations Peacekeeping The Limits of Jointness The Gulf War Service Redundancy: Waste or Hidden Capability? Revisited Joint Air Summer Operations 93 by Stephen Peter Rosen Inaugural Issue 36 Service Redundancy— Waste or Capability? A PROFESSIONAL MILITARY JOURNAL ABOUT THE COVER Reforming Joint Doctrine The cover shows USS Dwight D. Eisenhower, 40 by Robert A. Doughty passing through the Suez Canal during Opera- tion Desert Shield, a U.S. Navy photo by Frank A. Marquart. Photo credits for insets, from top United Nations Peacekeeping: Ends versus Means to bottom, are Schulzinger and Lombard (for 48 by William H. -

Military Law Review Vol. 83

Deportment of the Army Pamphlet 27-100-83 MILITARY LAW REVIEW VOL. 83 An International Law Symposium: Part II Introduction ARTICLES: International Law Under Contemporary Pressures Soviet International Law Today: An Elastic Dogma The Seizure and Recovery of the S.S. Mayaguez: A legal Analysis of United States Claims z6 BOOK REVIEWS: Sea Power and the Law of the Sea: The Need for a Contextual Approach Three SlPRl Publications PUBLICATIONS RECEIVED AND BRIEFLY NOTED INDEX Yeadquarten, Deportment of the Army Winter 1979 MILITARY LAW REVIEW EDITORIAL POLICY: The Military Law Review provides a forum for those interested in military law to share the products of their experience and research. Writings should be of direct concern and import in this area of scholarship, and preference will be given *tothose writings having lasting value as reference material for the military lawyer. The Military Lax Review does not purport to promulgate De- partment of the Army policy or to be in any sense directory. The opinions reflected in each writing are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Judge Advocate General or any governmental agency. Masculine pronouns appearing in the pam- phlet refer to both genders unless the context indicates another use. SUBMISSION OF WRITINGS: Articles, comments, recent de- velopment notes, and book reviews should be submitted in dupli- cate, typed double space, on letter-size paper (8 x 10% or 8% x 11). They should be submitted to the Editor, Military Law Review, The Judge Advocate General’s School, U. S. Army, Charlottesville, Vir- ginia 22901. -

The Luther Skald

The Luther Skald Vol. 1 No. 2 February 2013 Mortality and Medical Aging.…………………………………………………………………2 Laurie Medford Resistance: Empowering Norwegians and Creating Solidarity under Nazi Occupation.……35 Cassie Holstad The ‘Savage Oppressors’ of the Catholic Church: Creating Identity and Securing Authority at the Expense of the ‘Usurious’ Jew……………………...……………………………………54 Cate Anderson Using Lutherans for Doctrinal Homogeneity in New Spain………………………………….66 Andrew Ruud February 2013 The Luther Skald 2 MORTALITY AND MEDICAL AGING Laurie Medford “I OFTEN HEARD HIM SAY HIS HEALTH WAS BROKEN WHILE IN THE ARMEY”: THE SOCIAL PROFILE AND MEDICAL AGING OF WISCONSIN VETERANS “I DON’T THINK HE HAS BEEN HALF THE MAN SINCE THE WAR” In 1889, J. E. Murha, MD recalled medical experiences of some soldiers who served in the Eighth Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry during the Civil War. As the Assistant Surgeon for the regiment, Murha was asked to provide his knowledge of the circumstances of Private Daniel Wyman’s illness and the medical treatment Murha offered. His account, a brief affidavit, provides the first view into the health experience of an ordinary Union soldier. During the Fall of 1861 the 8th Regt Wis Infty Made a March from Pilot Knob Mo [Missouri] to the Arkansas Line, while on the March Measles broke out among men. I was then Asst [Assistant] Surgeon, there was no [unclear: “attendants”?] to care for so many sick. Cohort tents and exposed to cold of frosty night; [caused] to many [to] suffer from Pneumonia. Bronchitis. among them was D. Wyman of Co. C 8th Regt On the return of the Regt he was sent to the Post Hospital at Ironton Mo.1 A fellow member of Company “C,” Eighth Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry, Francis Schmidtmayer, amplifies Wyman’s story in his affidavit: “…Said Wyman rejoined his regiment while stationed at Sulphur Spring Mo. -

The Forgotten Footnote of the Second World War: an Examination of the Historiography of Scandinavia During World War II

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2013 The orF gotten Footnote of the Second World War: An Examination of the Historiography of Scandinavia during World War II Jason C. Phillips East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Phillips, Jason C., "The orF gotten Footnote of the Second World War: An Examination of the Historiography of Scandinavia during World War II" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1149. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1149 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Forgotten Footnote of the Second World War: An Examination of the Historiography of Scandinavia during World War II _____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Arts in History _____________________ by Jason Phillips May 2013 _____________________ Dr. Stephen G. Fritz, Chair Dr. Henry J. Antkiewicz Dr. Daryl A. Carter Keywords: Scandinavia, World War II, Modern Europe ABSTRACT The Forgotten Footnote of the Second World War: An Examination of the Historiography of Scandinavia during World War II by Jason Phillips The Anglo-American interpretation of the Second World War has continuously overlooked the significance of the Scandinavian region to the outcome of the war. -

Principles for Collective Humanitarian Intervention to Succor Other Countries' Imperiled Indigenous Nationals George K

American University International Law Review Volume 18 | Issue 1 Article 3 2002 Principles for Collective Humanitarian Intervention to Succor Other Countries' Imperiled Indigenous Nationals George K. Walker Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Parker, Elizabeth Rindskopf. "Principles for Collective Humanitarian Intervention to Succor Other Countries' Imperiled Indigenous Nationals." American University International Law Review 18, no. 1 (2002): 35-162. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRINCIPLES FOR COLLECTIVE HUMANITARIAN INTERVENTION TO SUCCOR OTHER COUNTRIES' IMPERILED INDIGENOUS NATIONALS GEORGE K. WALKER* I. ST A T E O F N E C E S SIT Y ........................................................................................ 4 0 II. TH E PRO PO SED PRIN CIPLES ................................................................. 55 A . P R IO R S ITU A T IO N S......................................................................................... 5 5 B. STATE OF NECESSITY: OPPOSING PRINCIPLES AND P OL IC IES ...................................................................................................................... -

Introduction 1 the Royal Navy and the Home Fleet: Men, Material

Notes Introduction 1. P. Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery (London: Ashfield Press, 1995 revised paper back ed.), p. 306. 2. For a modern account informed by Italian language sources, see J. Greene and A. Massignani, The Naval War in the Mediterranean 1940–1943 (Rochester, Kent: Chatham Publishing, 1998), pp. 63–81. 3. L. Kennedy, The Death of the Tirpitz (Boston: Little, Brown, 1979), p. 56 uses the term ‘much worry’; ‘bogeyman’ is from P. Kemp, Convoy! Drama in Arctic Waters (London: Arms Armour Press, 1993), p. 191; Rear Admiral W. H. Langenberg, USNR, in ‘The German Battleship Tirpitz: A Strategic Warship?’, Naval War College Review, 34 (4), p. 82, uses the term ‘concern’. See also T. Gallagher, The X-Craft Raid (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1969), chapter 2. 4. Langenberg, ‘The German Battleship Tirpitz’, p. 82. 1 The Royal Navy and the Home Fleet: Men, Material, Strategy 1919–39 1. This process is described in detail by P. Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery, pp. 205–37. However, the conventional view of naval policy ca 1900–14 has recently come under critical review; see, for example, J. T. Sumida, In Defence of Naval Supremacy (London: Routledge, 1993), N. Lambert, Sir John Fisher’s Naval Revolution (Columbia, SC: South Carolina University Press, 1999). Certainly, it was a cost-saving measure. But whether Britain employed a Dreadnought fleet or ‘flotilla defence’, it became clear between 1906 and 1912 that most of the Fleet would be needed in Home Waters if war with Germany erupted. -

Adobe PDF File

BOOK REVIEWS John B. Hattendorf (ed.). Maritime History, ignored, this merely reflects the fact that no Volume I: The Age of Discovery. Malabar, FL: book of this sort can possibly treat all potential Krieger Publishing, 1996. xv + 331 pp., illustra• topics. More disturbing, however, is the solidly tions, maps, tables, suggested readings, index. Eurocentric perspective: after all the work in US $29.50, paper; ISBN 0-89464-834-9. recent years by maritime scholars sensitive to non-European contributions, the sort of myopia Some instructors who teach undergraduate suggested by the volume's title is very much to courses on the age of exploration have long be regretted. complained about the lack of a suitable text• Unfortunately, the book is much less suc• book. The Age of Discovery, which contains cessful at introducing students to the main selected lectures from a National Endowment for debates in specialized fields than in providing a the Humanities-sponsored summer institute at broad survey. Without question the two most Brown University in 1992 edited by John B. solid sections in this regard are those on "The Hattendorf, currently Ernest J. King Professor of Late Medieval Background" and "Spain and the Maritime History at the Naval War College in Conquest of the Atlantic." Unger's prose is Newport, RI, is on one level planned to fill this always a delight, and his chapters here are no need. As a volume in Krieger's imaginative exception. The debates are clearly articulated, "Open Forum Series," it is also designed "to and a brief, but well chosen, selection of recom• summarize the latest interpretations in this field" mended readings will quickly take even neo• and to introduce "students to the wider litera• phytes to the heart of the various issues. -

Maritime Diplomacy in the 21St Century

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 20:29 19 May 2016 Maritime Diplomacy in the 21st Century This book aims to redefine maritime diplomacy for the modern era. Maritime diplomacy encompasses a spectrum of activities, from co- operative measures such as port visits, exercises and humanitarian assistance to persuasive deployment and coercion. It is an activity no longer confined to just navies, but in the modern era is pursued by coastguards, civilian vessels and non-state groups. As states such as China and India develop, they are increasingly using this most flexible form of soft and hard power. Maritime Diplomacy in the 21st Century describes and analyses the concept of maritime diplomacy, which has been largely neglected in academic literature. The use of such diplomacy can be interesting not just for the parochial effects of any activity, but because any event can reflect changes in the international order, while acting as an excellent gauge for the existence and severity of international tension. Further, maritime diplomacy can act as a valve through which any tension can be released without resort to conflict. Written in an accessible but authoritative style, this book describes the continued use of coercion outside of war by navies, while also situating it more clearly within the various roles and effects that maritime forces have in peacetime. This book will be of much interest to students of seapower, naval history, strategic studies, diplomacy and international relations. Christian Le Mière is a senior fellow for naval forces and maritime security at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, London. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 20:29 19 May 2016 Cass Series: Naval Policy and History Series Editor: Geoffrey Till ISSN 1366–9478 This series consists primarily of original manuscripts by research scholars in the general area of naval policy and history, without national or chronological lim- itations.