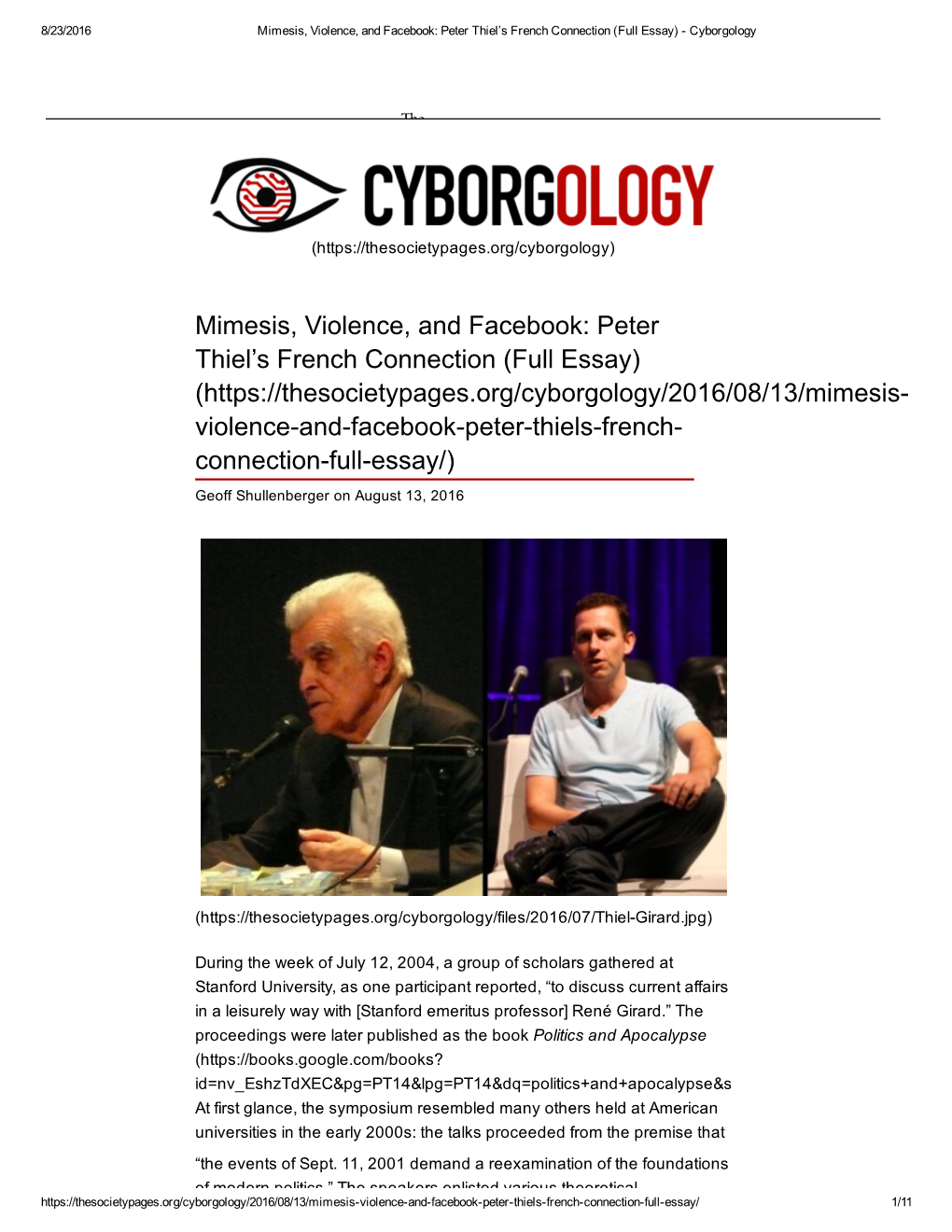

Mimesis, Violence, and Facebook: Peter Thiel's French Connection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mont Pelerin Society

A SPECIAL MEETING THE MONT PELERIN SOCIETY JANUARY 15–17, 2020 FROM THE PAST TO THE FUTURE: IDEAS AND ACTIONS FOR A FREE SOCIETY CHAPTER FORTY-ONE CHINA, GLOBALIZATION, CAPITALISM, SILICON VALLEY, POLITICAL CORRECTNESS, AND EXCEPTIONALISM PETER THIEL & PETER ROBINSON HOOVER INSTITUTION • STANFORD UNIVERSITY 1 1 China, Globalization, Capitalism, Silicon Valley, Political Correctness, and Exceptionalism A Conversation Between Peter Theil and Peter Robinson January 17, 2020 Peter Robinson: The late economist and foreign policy analyst Hoover fellow Henry Rowen writing in 1996, quote, "When will China become a democracy? "The answer is around the year 2015. "This prediction is based on China's steady "and impressive economic growth, "which in turn fits the pattern of the way in which freedom "has grown in Asia and elsewhere in the World." Worked in South Korea, worked in Taiwan. Economic growth leads to democracy. In China, what went wrong? Peter Thiel: Well, Peter, this is always a set up for me to start by both flattering you and criticizing you a little bit, since there was that very famous Reagan speech you gave, that you wrote for Reagan, where it was, you know, tear down that wall, Mr. Gorbachev, and it was very effective. But it was perhaps, it was not only in the West that we learned lessons from it, the Chinese communists also paid very careful attention to it, and they learned that you had to have perestroika without glasnost. You had to get rid of the Marxism without getting rid of the Leninism, and they learned somehow the very opposite lessons of that fateful year 1989. -

The Rise & Role of Venture Studios in Healthcare Innovation

The Rise & Role of Venture Studios in Healthcare Innovation Session # 195, August 12, 2021 Le s Wilkins on Chief Operating Officer, Hashed Health DISCLAIMER: The views and opinions expressed in this presentation are solely those of the author/presenter and do not necessarily represent any policy or position of HIMSS. 1 Welcome Le s Wilkins on Chief Operating Officer, Hashed Health #HIMSS21 2 Conflict of Interest Les Wilkinson, COO, Hashed Health Has no real or apparent conflicts of interest to report. #HIMSS21 3 Agenda • Current State of Innovation. • Studios are innovating innovation. • Studio value proposition. • Studio characteristics and structure. • Studio results. #HIMSS21 4 Learning Objectives – By the end of this session, the audience will be able to: • State common reasons healthcare startups fail and how new innovation models can de-risk the innovation process. • Describe traditional corporate innovation challenges in her/his own words. • Design a venture studio process for moving ideas to commercialization. • Apply the principles of a venture studio process to their own innovation efforts. • Identify how to differentiate between accelerators, incubators, corporate innovation programs and new venture studio models. • Recognize whether a venture studio model could be a fit for their organization. #HIMSS21 5 Startup Mythology The Garage 6 Startup Reality >90% 75% 1% Percentage of Venture Backed Startup Failure Rate Companies that NEVER Return Cash Odds of achieving Unicorn Status to Investors Source: Startup Genome, 2019 Source: CBInsights Report Source: Failory #HIMSS21 7 No Market Need Ran Out of Cash Poor User Experience Why Not the Right Team Startups Fail Pricing and COGS Competition Source: CBInsights #HIMSS21 8 Innovation is a Priority for Enterprise . -

Facebook Timeline

Facebook Timeline 2003 October • Mark Zuckerberg releases Facemash, the predecessor to Facebook. It was described as a Harvard University version of Hot or Not. 2004 January • Zuckerberg begins writing Facebook. • Zuckerberg registers thefacebook.com domain. February • Zuckerberg launches Facebook on February 4. 650 Harvard students joined thefacebook.com in the first week of launch. March • Facebook expands to MIT, Boston University, Boston College, Northeastern University, Stanford University, Dartmouth College, Columbia University, and Yale University. April • Zuckerberg, Dustin Moskovitz, and Eduardo Saverin form Thefacebook.com LLC, a partnership. June • Facebook receives its first investment from PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel for US$500,000. • Facebook incorporates into a new company, and Napster co-founder Sean Parker becomes its president. • Facebook moves its base of operations to Palo Alto, California. N. Lee, Facebook Nation, DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4614-5308-6, 211 Ó Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 212 Facebook Timeline August • To compete with growing campus-only service i2hub, Zuckerberg launches Wirehog. It is a precursor to Facebook Platform applications. September • ConnectU files a lawsuit against Zuckerberg and other Facebook founders, resulting in a $65 million settlement. October • Maurice Werdegar of WTI Partner provides Facebook a $300,000 three-year credit line. December • Facebook achieves its one millionth registered user. 2005 February • Maurice Werdegar of WTI Partner provides Facebook a second $300,000 credit line and a $25,000 equity investment. April • Venture capital firm Accel Partners invests $12.7 million into Facebook. Accel’s partner and President Jim Breyer also puts up $1 million of his own money. -

Peter Thiel: What the Future Looks Like

Peter Thiel: What The Future Looks Like Peter Thiel: Hello, this is Peter. James Altucher: Hey, Peter. This is James Altucher. Peter Thiel: Hi, how are you doing? James Altucher: Good, Peter. Thanks so much for taking the time. I’m really excited for this interview. Peter Thiel: Absolutely. Thank you so much for having me on your show. James Altucher: Oh, no problem. So I’m gonna introduce you, but first I wanna mention congratulations your book – by the time your podcast comes out, your book will have just come out, Zero to One: Notes on Startups or How to Build a Future, and, Peter, we’re just gonna dive right into it. Peter Thiel: That’s awesome. James Altucher: So I want – before I break – I wanna actually, like, break down the title almost word by word, but before I do that, I want you to tell me what the most important thing that’s happened to you today because I feel like you’re – like, every other day you’re starting, like a Facebook or a PayPal or a SpaceX or whatever. What happened to you today that you looked at? Like, what interesting things do you do on a daily basis? Peter Thiel: Well, it’s – I don’t know that there’s a single thing that’s the same from day to day, but there’s always an inspiring number of great technology ideas, great science ideas that people are working on, and so even though there are many different reasons that I have concerns about the future and trends that I don’t like in our society and in the larger world, one of the things that always gives me hope is how much people are still trying to do, how many new technologies they’re trying to build. -

PETER THIEL Palantir Technologies; Thiel Foundation; Founders Fund; Paypal Co-Founder

Program on SCIENCE & DEMOCRACY Science, Technology & Society LECTURE SERIES 2015 HARVARD KENNEDY SCHOOL HARVARD UNIVERSITY PETER THIEL Palantir Technologies; Thiel Foundation; Founders Fund; PayPal co-founder BACK TO THE FUTURE Will we create enough new technology to sustain our society? WITH PANELISTS WEDNESDAY Antoine Picon Travelstead Professor, Harvard Graduate School of Design March 25, 2015 Margo Seltzer Harvard College Professor, School of Engineering and 5:00-7:00pm Applied Sciences Science Center Samuel Moyn Professor of Law and History, Harvard Law School Lecture Hall C 1 Oxford Street MODERATED BY Sheila Jasanoff Harvard University Pforzheimer Professor of Science and Technology Studies CO-SPONSORED BY Program on Harvard University Harvard School of Harvard University Center for the Engineering and Graduate School Science, Technology & Society Environment Applied Sciences of Design HARVARD KENNEDY SCHOOL HARVARD UNIVERSITY http://sts.hks.harvard.edu/ Program on SCIENCE & DEMOCRACY Science, Technology & Society LECTURE SERIES 2015 HARVARD KENNEDY SCHOOL HARVARD UNIVERSITY Peter Thiel is an entrepreneur and investor. He started PayPal in 1998, led it as CEO, and took it public in 2002, defining a new era of fast and secure online commerce. In 2004 he made the first outside investment in Facebook, where he serves as a director. The same year he launched Palantir Technologies, a software company that harnesses computers to empower human analysts in fields like national security and global finance. He has provided early funding for LinkedIn, Yelp, and dozens of successful technology startups, many run by former colleagues who have been dubbed the “PayPal Mafia.” He is a partner at Founders Fund, a Silicon Valley venture capital firm that has funded companies like SpaceX and Airbnb. -

Uncommon Knowledge Peter Thiel at MPS Script

January 17, 2020 PETER THIEL The World According to Thiel INTRODUCTION: Welcome to Uncommon Knowledge. I’m Peter Robinson. Born in Germany, Peter Thiel moved to the United States with his family when he was a child. He graduated from Stanford and then from Stanford law school. After deciding not to practice law, he co-founded PayPal and Palantir, made the first outside investment in Facebook, funded companies such as SpaceX and LinkedIn, and started the Thiel Fellowship, which encourages young people to drop out of college to start their own businesses. Mr. Thiel remains a very active tech investor, now based in Los Angeles. Peter, welcome. From the speech you delivered at the Republican convention in the summer of 2016: “When Donald Trump asks us to ‘Make America Great Again,’ he’s not suggesting a return to the past. He’s running to lead us back to…[the] bright future.” Three-and-a-half years later, how do you feel? Are you optimistic? Peter Thiel Page 1 of 11 SEGMENT ONE: The problem of scale You speak of “four vectors of globalization.” The movement of goods—free trade. The movement of people— immigration. The movement of capital—banking and finance. The movement of ideas—the Internet. You argue that on the first two—the movement of goods and the movement of people—“we simply cannot compete with China.” Why not? [Movement of goods: Seven of the 10 biggest container ship ports are in China. Our largest, in Los Angeles, ranks eleventh.] [Movement of people: In 1980, Shenzhen had a population of 60,000. -

Time to Fix It: Developing Rules for Internet Capitalism

Time to Fix It: Developing Rules for Internet Capitalism Tom Wheeler August 2018 M-RCBG Associate Working Paper Series | No. 96 The views expressed in the M-RCBG Associate Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business & Government or of Harvard University. The papers in this series have not undergone formal review and approval; they are presented to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. Copyright belongs to the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business & Government Weil Hall | Harvard Kennedy School | www.hks.harvard.edu/mrcbg Table of Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Corporate Citizenship 5 3. Historical Analog 7 4. Regulatory Uncertainty 9 5. Embracing Certainty 10 6. New Challenge, New Solutions 13 7. Internet Capitalism 15 8. Endnotes 16 2 Introduction “Modern technology platforms such as Google, Facebook, Amazon and Apple are even more powerful than most people realize,” Eric Schmidt wrote in 2013 when he was Executive Chairman of Google’s parent Alphabet, Inc.1 In the years since, that power and its effects on society has only increased – as has the public’s apprehension about the power of technology. Multiple times daily, each of us experiences the benefits offered by these platforms. From the ability to search the world’s knowledge, to communicating with friends, to hailing a taxi or ordering a pizza, the digital platforms – enabled by digital networks – have transformed our lives. At the same time, these digital platforms have aided Russian interference in the electoral process, impacted child development, and propagated disinformation, bigotry, and hateful speech. -

Your Post Has Been Removed

Frederik Stjernfelt & Anne Mette Lauritzen YOUR POST HAS BEEN REMOVED Tech Giants and Freedom of Speech Your Post has been Removed Frederik Stjernfelt Anne Mette Lauritzen Your Post has been Removed Tech Giants and Freedom of Speech Frederik Stjernfelt Anne Mette Lauritzen Humanomics Center, Center for Information and Communication/AAU Bubble Studies Aalborg University University of Copenhagen Copenhagen København S, København SV, København, Denmark København, Denmark ISBN 978-3-030-25967-9 ISBN 978-3-030-25968-6 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25968-6 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permit- ted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

Social Media Monopolies and Their Alternatives 2

EDITED BY GEERT LOVINK AND MIRIAM RASCH INC READER #8 The Unlike Us Reader offers a critical examination of social media, bringing together theoretical essays, personal discussions, and artistic manifestos. How can we understand the social media we use everyday, or consciously choose not to use? We know very well that monopolies control social media, but what are the alternatives? While Facebook continues to increase its user population and combines loose privacy restrictions with control over data, many researchers, programmers, and activists turn towards MIRIAM RASCH designing a decentralized future. Through understanding the big networks from within, be it by philosophy or art, new perspectives emerge. AND Unlike Us is a research network of artists, designers, scholars, activists, and programmers, with the aim to combine a critique of the dominant social media platforms with work on ‘alternatives in social media’, through workshops, conferences, online dialogues, and publications. Everyone is invited to be a part of the public discussion on how we want to shape the network architectures and the future of social networks we are using so intensely. LOVINK GEERT www.networkcultures.org/unlikeus Contributors: Solon Barocas, Caroline Bassett, Tatiana Bazzichelli, David Beer, David M. Berry, Mercedes Bunz, Florencio Cabello, Paolo Cirio, Joan Donovan, EDITED BY Louis Doulas, Leighton Evans, Marta G. Franco, Robert W. Gehl, Seda Gürses, Alexandra Haché, Harry Halpin, Mariann Hardey, Pavlos Hatzopoulos, Yuk Hui, Ippolita, Nathan Jurgenson, Nelli Kambouri, Jenny Kennedy, Ganaele Langlois, Simona Lodi, Alessandro Ludovico, Tiziana Mancinelli, Andrew McNicol, Andrea Miconi, Arvind Narayanan, Wyatt Niehaus, Korinna Patelis, PJ Rey, Sebastian SOCIAL MEDIA MONOPOLIES Sevignani, Bernard Stiegler, Marc Stumpel, Tiziana Terranova, Vincent Toubiana, AND THEIR ALTERNATIVES Brad Troemel, Lonneke van der Velden, Martin Warnke and D.E. -

Katrin Yr Magnusdottir Og Olafu

153.548 = 107 pages Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to analyze business model innovation in the social media industry. This industry of extraordinary growth and continuous technological development is driven by high level of investment from venture capitalists in their quest to find the next Facebook or the next Instagram. By conducting case studies on seven successful venture capital founded social media companies we want to map key similarities and differences in their business models. By creating a theoretical framework; the 7 Factor Model and combining it to the Business Model Canvas we identify scalability, uniqueness, loyalty, profitability, sustainability, mobility and inimitability as key value drivers. Based on our findings from the case studies we conclude that the design of business model influences the success of a social media start-up company and state that business model innovation is an important issue for these companies to react and gain competitive advantage in a world of constantly changing condition. Table of Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1. Foreword ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.2. Problem formulation .................................................................................................................................. 7 -

Lessons from Silicon Valley

Lessons From Silicon Valley Cathy Anterasian Spencer Stuart, Silicon Valley Jeff Hauswirth Spencer Stuart, Toronto Today’s Discussion > Silicon Valley overview > Key factors that make it unique > Opportunities for Canada Silicon Valley Overview > Where? Southern part of the San Francisco > Boasts 10 of the most inventive towns in the Bay Area in Northern California U.S. (Wall Street Journal) > Diverse Population of 2.5 million > Has “World Class” Universities • White: 41% (Stanford, Berkeley) • Asian: 28% • Hispanic: 25% > One in five has a graduate or post graduate • African American: 3% degree; one in four is a university grad • Native American: 1% • Other 3% > Very high concentration of Fortune 1000 tech firms (Adobe, Apple, Business Objects, eBay, > Average Wages: $73,300 Google, HP, Intel, Sun MicroSystems) > Amongst the highest real estate and cost of > “HQ” of thousands of others living > About 30% of all venture capital in the U.S. is spent in Silicon Valley Counter Great Culture Universities Innovative Critical Mass Financing History Military Venture Catalysts Complex Capitalists Risk Pioneers Takers Silicon Great Start-up Climate Valley Scene Relaxed Tolerance Atmosphere of Failure Lack of Tolerance Hierarchy of “Crazy Ideas” Information Highly Freeflow Creative Dense Fiercely Social Competitive Networks Culture & Lifestyle The Pioneers Fred Terman Bill Hewlett William Shockley David Packard “The Fairchild Eight” The Lure and Contributions of Great Universities In Silicon Valley Big Companies…Seed Many New Stars Formed Among the Estimated 70 Companies that Fairchild Semiconductor Spawned… Critical Mass of Venture Capital Infrastructure and Specialized Services > Office space > Lawyers > Accountants > Investment Bankers > Executive Recruiters > Marketing Consultants > Etc. Risk Taking Dream Big… …It’s OK to fail… …As long as you learn Think Big “From the beginning at Intel, we planned on being big. -

Facebookfrom Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopediajump To: Navigation, Search This Article Is About the Website

FacebookFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaJump to: navigation, search This article is about the website. For the collection of photographs of people after which it is named, see Facebook (directory(directory).). Facebook, Inc. Type Private Founded Cambridge, MassachusettsMassachusetts[1][1] (2004 (2004)) Founder Mark Zuckerberg Eduardo Saverin Dustin Moskovitz Chris Hughes HeadquarterHeadquarterss Palo Alto, California, U.S., will be moved to MenMenlolo Park, California, U.S. in June 2011 Area served Worldwide Key people Mark Zuckerberg (CEO) Chris Cox (VP of Product) Sheryl Sandberg (COO) Donald E. Graham (Chairman) Revenue US$800 mmillionillion (2009 est.)[2] Net income N/A This website stores data such as cookies to enableEmployees essential 2000+(2011)[3] site functionality, as well as marketing, personalization,Website and analytics. facebook.com You may change your settings at any time or accept theIPv6 default support settings. www.v6.fawww.v6.facebook.comcebook.com Alexa rank 2 (Ma(Marchrch 2011[upda2011[update][4])te][4]) Privacy Policy Type of site Social networking service Marketing PersonalizationAdvertising Banner ads, referral marketing, casual games AnalyticsRegistration Required Save Accept All Users 600 million[5][6] (active in January 2011) Available in Multilingual Launched February 4, 2004 Current status Active Screenshot[show] Screenshot of Facebook's homepage Facebook (stylized facebook) is a social networking service and website launched in February 2004, operated and privately owned by Facebook, Inc.[1] As of January 2011[update], Facebook has more than 600 million active users.[5][6] Users may create a personal profile, add other users as friends, and exchange messages, including automatic notifications when they update their profile.