Concise History of the Afghanistan-Pakistan War No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CMR May 2019.Cdr

MONITOR Civil-Military Relations in Pakistan May 2019 Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development And Transparency PILDAT Monitor CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS IN PAKISTAN May 2019 In this Issue This monitor is meant to identify key developments during the month on Civil Military Relations in Pakistan with selected high-profile international developments included occasionally. 1. Kharqamar Incident 2. Presidential Reference against Kharqamar Incident Judges 3. COAS endorses punishments for army/civilian officers for espionage On May 26, 2019, the ISPR, in a Press Release, announced that Mr. Mohsin Javed (Dawar), 4. 221st Corps Commanders' MNA, and Mr. Ali Wazir, MNA, 'assaulted' Kharqamar check-post in Boyya, North Waziristan Conference district. The ISPR alleged that the group was armed and that “due to firing of the group, 5 Army 5. Army Chief addresses Students in soldiers got injured. In exchange of fire, 3 individuals, who attacked the post, lost their lives and Peshawar 10 got injured.” According to the statement, a group led by the MNAs wanted to exert pressure 6. COAS meets Foreign Dignitaries for the release of 'suspected terrorists' facilitator' arrested some days ago. Mr. Ali Wazir, MNA, was arrested along with 8 other individuals while Mr. Mohsin Dawar, MNA, was declared to be 7. Meeting of the National Security 1 Committee 'at large'. On May 29, Mr. Mohsin Dawar, MNA, presented himself for arrest after a long round 8. PM-COAS Interactions of negotiations between tribal elders and district administration. He was presented before an 9. International Developments Anti-terrorism court in Bannu before being shifted to Peshawar on a week-long physical remand in the custody of Counter-Terrorism Department (CTD). -

Supreme Soviet Investigation of the 1991 Coup the Suppressed Transcripts

Supreme Soviet Investigation of the 1991 Coup The Suppressed Transcripts: Part 3 Hearings "About the Illegal Financia) Activity of the CPSU" Editor 's Introduction At the birth of the independent Russian Federation, the country's most pro-Western reformers looked to the West to help fund economic reforms and social safety nets for those most vulnerable to the change. However, unlike the nomenklatura and party bureaucrats who remained positioned to administer huge aid infusions, these reformers were skeptical about multibillion-dollar Western loans and credits. Instead, they wanted the West to help them with a different source of money: the gold, platinum, diamonds, and billions of dollars in hard currency the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) and KGB intelligence service laundered abroad in the last years of perestroika. Paradoxically, Western governments generously supplied the loans and credits, but did next to nothing to support the small band of reformers who sought the return of fortunes-estimated in the tens of billions of dollars- stolen by the Soviet leadership. Meanwhile, as some in the West have chronicled, the nomenklatura and other functionaries who remained in positions of power used the massive infusion of Western aid to enrich themselves-and impoverish the nation-further. In late 1995, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development concluded that Russian officials had stolen $45 billion in Western aid and deposited the money abroad. Radical reformers in the Russian Federation Supreme Soviet, the parliament that served until its building was destroyed on President Boris Yeltsin's orders in October 1993, were aware of this mass theft from the beginning and conducted their own investigation as part of the only public probe into the causes and circumstances of the 1991 coup attempt against Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev. -

The Blind Leading the Blind

WORKING PAPER #60 The Blind Leading the Blind: Soviet Advisors, Counter-Insurgency and Nation-Building in Afghanistan By Artemy Kalinovsky, January 2010 COLD War INTernaTionaL HISTorY ProjecT Working Paper No. 60 The Blind Leading the Blind: Soviet Advisors, Counter-Insurgency and Nation-Building in Afghanistan By Artemy Kalinovsky THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES Christian F. Ostermann and Mircea Munteanu Series Editors This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. The project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War, and seeks to accelerate the process of integrating new sources, materials and perspectives from the former “Communist bloc” with the historiography of the Cold War which has been written over the past few decades largely by Western scholars reliant on Western archival sources. It also seeks to transcend barriers of language, geography, and regional specialization to create new links among scholars interested in Cold War history. Among the activities undertaken by the project to promote this aim are a periodic BULLETIN to disseminate new findings, views, and activities pertaining to Cold War history; a fellowship program for young historians from the former Communist bloc to conduct archival research and study Cold War history in the United States; international scholarly meetings, conferences, and seminars; and publications. -

Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence

Russia • Military / Security Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, No. 5 PRINGLE At its peak, the KGB (Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti) was the largest HISTORICAL secret police and espionage organization in the world. It became so influential DICTIONARY OF in Soviet politics that several of its directors moved on to become premiers of the Soviet Union. In fact, Russian president Vladimir V. Putin is a former head of the KGB. The GRU (Glavnoe Razvedvitelnoe Upravleniye) is the principal intelligence unit of the Russian armed forces, having been established in 1920 by Leon Trotsky during the Russian civil war. It was the first subordinate to the KGB, and although the KGB broke up with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the GRU remains intact, cohesive, highly efficient, and with far greater resources than its civilian counterparts. & The KGB and GRU are just two of the many Russian and Soviet intelli- gence agencies covered in Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence. Through a list of acronyms and abbreviations, a chronology, an introductory HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF essay, a bibliography, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries, a clear picture of this subject is presented. Entries also cover Russian and Soviet leaders, leading intelligence and security officers, the Lenin and Stalin purges, the gulag, and noted espionage cases. INTELLIGENCE Robert W. Pringle is a former foreign service officer and intelligence analyst RUSSIAN with a lifelong interest in Russian security. He has served as a diplomat and intelligence professional in Africa, the former Soviet Union, and Eastern Europe. For orders and information please contact the publisher && SOVIET Scarecrow Press, Inc. -

BATTLE-SCARRED and DIRTY: US ARMY TACTICAL LEADERSHIP in the MEDITERRANEAN THEATER, 1942-1943 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial

BATTLE-SCARRED AND DIRTY: US ARMY TACTICAL LEADERSHIP IN THE MEDITERRANEAN THEATER, 1942-1943 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Steven Thomas Barry Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Allan R. Millett, Adviser Dr. John F. Guilmartin Dr. John L. Brooke Copyright by Steven T. Barry 2011 Abstract Throughout the North African and Sicilian campaigns of World War II, the battalion leadership exercised by United States regular army officers provided the essential component that contributed to battlefield success and combat effectiveness despite deficiencies in equipment, organization, mobilization, and inadequate operational leadership. Essentially, without the regular army battalion leaders, US units could not have functioned tactically early in the war. For both Operations TORCH and HUSKY, the US Army did not possess the leadership or staffs at the corps level to consistently coordinate combined arms maneuver with air and sea power. The battalion leadership brought discipline, maturity, experience, and the ability to translate common operational guidance into tactical reality. Many US officers shared the same ―Old Army‖ skill sets in their early career. Across the Army in the 1930s, these officers developed familiarity with the systems and doctrine that would prove crucial in the combined arms operations of the Second World War. The battalion tactical leadership overcame lackluster operational and strategic guidance and other significant handicaps to execute the first Mediterranean Theater of Operations campaigns. Three sets of factors shaped this pivotal group of men. First, all of these officers were shaped by pre-war experiences. -

The Collapse of the Soviet Union (Part 1) Introduction

IntroductionKramer SPECIAL ISSUE: The Collapse of the Soviet Union (Part 1) Introduction ✣ The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 was remarkable because it occurred so suddenly and with so little violence, especially in Russia itself. Even now, more than a decade after the fact, the abrupt and largely peaceful end of Communist rule in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union seems nearly miraculous. History offers no previous instances in which revolutionary polit- ical and social change of this magnitude transpired with almost no violence. When large, multiethnic empires disintegrated in the past, their demise usu- ally came after extensive warfare and bloodshed.1 As late as mid-August 1991, just before an attempted coup d’état in Moscow, few if any observers expected that the Soviet Communist regime—and the Soviet state as a whole—would simply dissolve in a nonviolent manner. Many long-standing Western theo- ries of revolution and political change will have to be revised to take account of the largely peaceful upheavals that culminated in the breakup of the Soviet Union. Despite the enormous signiªcance of the Soviet collapse, Western schol- ars have not yet adequately explained why and how it occurred. Although a plethora of articles and books on the subject have been published over the past eleven years, the cumulative results of this research have been modest.2 The basic chronology of events from 1985 through 1991 is well-known, but the details of many crucial episodes (such as the failed coup of August 1991) are as murky as ever. There has not yet been a systematic, in-depth assessment 1. -

C:\Users\The Kabul Times\Deskto

Nation Thursday, March 12, 2020 Rada Akbar's second Why Pakistani military threatened by warm welcome given to PTM leaders in Afghanistan "Superwomen" exhibition “The state machinery is used against Pashtuns & other minorities who speak for their opens in Kabul constitutional rights & challenges the undemocratic forces running affairs of state.” The Abarzanan, or '"Su- signing these art pieces depict- exhibition, a sculpture of perwomen" exhibit opened on ing women. Rukhshana, a girl stoned by the March 8 - International Wom- Sixteen influential women, Taliban four years ago in Ghor en's Day--as a celebration of including Roya Sadat, a film- province, was also displayed. the authority and historical maker; Khalida Popalzai, a Visitors say that such works role of Afghan women in the footballer; Parwen, a 40s coun- of art have a great positive im- world, said artist and organiz- try singer and other women pact on society. er Rada Akbar. who have fought violence and “When we read about these The exhibit will be opened inequality are represented in women’s pasts, those who have until March 22, at Chihilsitoon the exhibit. oppressed them, we see that Palace. “The hands we used in these they were very heroic women,” The exhibition aims to statues are a symbol of vio- said Nigena, a visitor. showcase women's struggles to lence, which is used in the “It's a moment of joy when achieve their rights. name of politics, in the name women can work shoulder to The "Superwomen’ exhib- of economics or in the name of shoulder with men in the soci- it has been running for two religion against women,” said ety,” said Mida Gul, another years, and Rada Akbar has spent Rada Akbar, artist. -

Michael Pye Phd Thesis

IN THE BELLY OF THE BEAR? SOVIET-IRANIAN RELATIONS DURING THE REIGN OF MOHAMMAD REZA PAHLAVI Michael Pye A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2015 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/9501 This item is protected by original copyright IN THE BELLY OF THE BEAR? SOVIET-IRANIAN RELATIONS DURING THE REIGN OF MOHAMMAD REZA PAHLAVI CANDIDATE: MICHAEL PYE DEGREE: DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DATE OF SUBMISSION: 26TH OF MAY 2015 1 ABSTRACT The question mark of the project's title alludes to a critical reexamination of Soviet- Iranian relations during the period and aims to offer an original contribution to scholarship in the field by exploring an aspect of Pahlavi foreign relations that lacks any detailed treatment in the literature presently available. In pursuit of this goal, research has been concentrated on recently-released western archival documentation, the Iranian Studies collection held at the University of St Andrews, and similarly materials from the Russian Federal Archive for Foreign Relations, to which the author was granted access, including ambassadorial papers relating to the premiership of Mohammad Mosaddeq. As far as can be ascertained, the majority of the Russian archival evidence presented in the dissertation has not been previously been utilised by any Western-based scholar. At core, the thesis argues that the trajectory of Pahlavi foreign relations specifically (and to a certain degree Mohammad Reza's regency more broadly) owed principally to a deeply-rooted belief in, and perceived necessity to guard against, the Soviet Union's (and Russia's) historical 'objectives' vis-à-vis Iran. -

Crisiswatch | Crisis Group 01/07/2019 22�52

CrisisWatch | Crisis Group 01/07/2019 2252 CrisisWatch Tracking Conflict Worldwide BROWSE MAP 2 SCROLL DOWN TO READ TRENDS & OUTLOOK CrisisWatchAFRICA is our global conflict tracker, a tool designed to help decision-makers prevent deadly violence by keeping them up-to-date with developments in over 70 conflicts and crises, identifying trends and alerting them to risks of escalation and opportunities to advance peace. ASIA Learn more about CrisisWatch EUROPE & CENTRAL ASIA GLOBAL OVERVIEW SEARCH DATABASE PRESIDENT'S TAKE USING CRISISWATCH ABOUT SUBSCRIBE LATIN AMERICA & CARIBBEAN MIDDLE EAST & NORTH AFRICA Global Overview JUNE 2019 UNITED STATES In June, Iran-U.S. tensions continued to climb, GLOBAL ISSUES raising the risk of a military conflagration. Yemen’s Outlook for This Month July 2019 Huthi forces, seen as Iran-backed, increased the VISUAL pace of strikes in Saudi Arabia, which in turn Conflict Risk Alerts EXPLAINERS stepped up bombing in Yemen. Attacks on U.S. Mali, CRISISWATCH assets in Iraq multiplied, and protests erupted in the Democratic Republic of Congo, south. High-level assassinations rocked Ethiopia, Malawi, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Algeria REPORTS & and Sudan’s security forces reportedly killed over BRIEFINGS 120 protesters. Major ethnic violence hit north east Resolution Opportunities DR Congo and Mali’s centre and could escalate in ARCHIVE None both places. In Cameroon, violence raged in Anglophone areas and Boko Haram upped attacks. Political tensions rose in Guinea, Malawi and Tunisia, and Algeria could enter a constitutional Trends for Last Month void in July, possibly inflaming protests and June 2019 repression. In both Honduras and Haiti, anti- https://www.crisisgroup.org/crisiswatch#overview Page 1 sur 43 CrisisWatch | Crisis Group 01/07/2019 2252 MY READING LIST repression. -

Style Attacks and the Threat from Lashkar-E-Taiba

PROTECTING THE HOMELAND AGAINST MUMBAI- STYLE ATTACKS AND THE THREAT FROM LASHKAR-E-TAIBA HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON COUNTERTERRORISM AND INTELLIGENCE OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 12, 2013 Serial No. 113–21 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 85–686 PDF WASHINGTON : 2013 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas, Chairman LAMAR SMITH, Texas BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi PETER T. KING, New York LORETTA SANCHEZ, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas PAUL C. BROUN, Georgia YVETTE D. CLARKE, New York CANDICE S. MILLER, Michigan, Vice Chair BRIAN HIGGINS, New York PATRICK MEEHAN, Pennsylvania CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania RON BARBER, Arizona JASON CHAFFETZ, Utah DONDALD M. PAYNE, JR., New Jersey STEVEN M. PALAZZO, Mississippi BETO O’ROURKE, Texas LOU BARLETTA, Pennsylvania TULSI GABBARD, Hawaii CHRIS STEWART, Utah FILEMON VELA, Texas RICHARD HUDSON, North Carolina STEVEN A. HORSFORD, Nevada STEVE DAINES, Montana ERIC SWALWELL, California SUSAN W. BROOKS, Indiana SCOTT PERRY, Pennsylvania MARK SANFORD, South Carolina GREG HILL, Chief of Staff MICHAEL GEFFROY, Deputy Chief of Staff/Chief Counsel MICHAEL S. TWINCHEK, Chief Clerk I. LANIER AVANT, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON COUNTERTERRORISM AND INTELLIGENCE PETER T. -

Requests Report

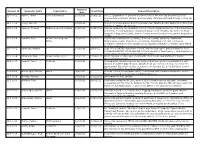

Received Request ID Requester Name Organization Closed Date Request Description Date 12-F-0001 Vahter, Tarmo Eesti Ajalehed AS 10/3/2011 3/19/2012 All U.S. Department of Defense documents about the meeting between Estonian president Arnold Ruutel (Ruutel) and Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney on July 19, 1991. 12-F-0002 Jeung, Michelle - 10/3/2011 - Copies of correspondence from Congresswoman Shelley Berkley and/or her office from January 1, 1999 to the present. 12-F-0003 Lemmer, Thomas McKenna Long & Aldridge 10/3/2011 11/22/2011 Records relating to the regulatory history of the following provisions of the Department of Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS), the former Defense Acquisition Regulation (DAR), and the former Armed Services Procurement Regulation (ASPR). 12-F-0004 Tambini, Peter Weitz Luxenberg Law 10/3/2011 12/12/2011 Documents relating to the purchase, delivery, testing, sampling, installation, Office maintenance, repair, abatement, conversion, demolition, removal of asbestos containing materials and/or equipment incorporating asbestos-containing parts within its in the Pentagon. 12-F-0005 Ravnitzky, Michael - 10/3/2011 2/9/2012 Copy of the contract statement of work, and the final report and presentation from Contract MDA9720110005 awarded to the University of New Mexico. I would prefer to receive these documents electronically if possible. 12-F-0006 Claybrook, Rick Crowell & Moring LLP 10/3/2011 12/29/2011 All interagency or other agreements with effect to use USA Staffing for human resources management. 12-F-0007 Leopold, Jason Truthout 10/4/2011 - All documents revolving around the decision that was made to administer the anti- malarial drug MEFLOQUINE (aka LARIAM) to all war on terror detainees held at the Guantanamo Bay prison facility as stated in the January 23, 2002, Infection Control Standard Operating Procedure (SOP). -

ASPS 2015 Program

THE SEVENTH BIENNIAL CONVENTION OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR THE STUDY OF PERSIANATE SOCIETIES (ASPS) ASPS/Istanbul 2015 September 8-11, 2015 Istanbul, Turkey VENUE MIMAR SINAN FINE ARTS UNIVERSITY, FINDIKLI CAMPUS Address: Meclis-i Mebusan Caddesi No: 24 Fındıklı 34427, Beyoğlu, İstanbul Website: http://www.msgsu.edu.tr/tr-TR/findikli/606/Page.aspx Telephone: 0212 252 16 00 THE ASSOCIATION FOR THE STUDY OF PERSIANATE SOCIETIES PRESIDENT Saïd Amir Arjomand State University of New York, Stony Brook VICE PRESIDENT Jo-Ann Gross The College of New Jersey ACTING TREASURER Pooriya Alimoradi University of Toronto PAST-PRESIDENTS Parvaneh Pourshariati Institute for the Study of Ancient World (ISAW/NYU and CUNY) Rudi Matthee University of Delaware FOUNDER & PAST-PRESIDENT Saïd Amir Arjomand State University of New York Stony Brook BOARD OF DIRECTORS Pooriya Alimoradi University of Toronto Sussan Babaie The Courtauld Institute of Art Kathryn Babayan University of Michigan 2 Houchang Chehabi Boston University Ghazzal Dabiri University of Ghent Rudi Matthee University of Delaware Jawid Mojaddedi Rutgers University Judith Pfeiffer University of Oxford 3 REGIONAL OFFICE DIRECTORS ARMENIA Garnik Asatrian Caucasian Center for Iranian Studies, Yerevan BALKANS Ahmed Zildžić, The Oriental Institute, Sarajevo COUNCIL FOR EURASIA Florian Schwarz Austrian Academy of Sciences GEORGIA George Sanikidze Institute of Oriental Studies, Tbilisi INDIA Isthtiyaq Ahmad Zilli Aligarh Muslim University IRAN Kourosh Kamali Fars Encyclopedia, Shiraz, Iran PAKISTAN Muhammad Saleem