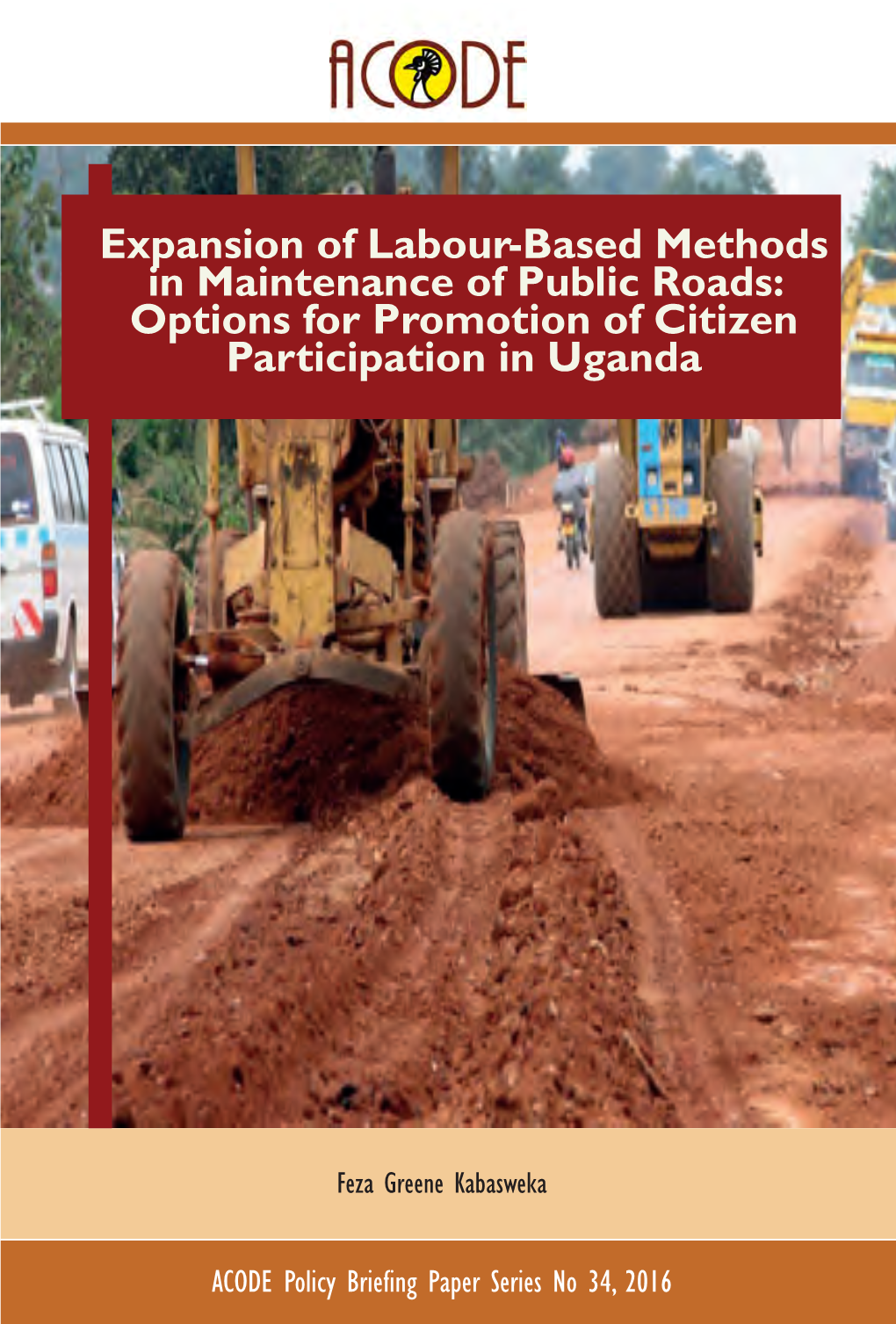

Expansion of Labour-Based Methods in Maintenance of Public Roads: Options for Promotion of Citizen Participation in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Republic of Uganda

The Republic of Uganda A VALUE FOR MONEY AUDIT REPORT ON REHABILITATION AND MAINTENANCE OF FEEDER ROADS IN UGANDA: A CASE STUDY OF HOIMA, KUMI, MASINDI, MUKONO AND WAKISO DISTRICTS Prepared by Office of the Auditor General P.O. Box 7083 Kampala FEBRUARY, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES, FIGURES AND PICTURES..................................................................................... iv LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................... v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ vi CHAPTER 1 ............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background to the audit .................................................................................. 1 1.2 Motivation ...................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Description of the audit area ........................................................................... 2 CHAPTER 2 ............................................................................................................................................. 7 2.0 AUDIT METHODOLOGY ..................................................................................... -

Uganda Road Fund Annual Report FY 2011-12

ANNUAL REPORT 2011-12 Telephone : 256 41 4707 000 Ministry of Finance, Planning : 256 41 4232 095 & Economic Development Fax : 256 41 4230 163 Plot 2-12, Apollo Kaggwa Road : 256 41 4343 023 P.O. Box 8147 : 256 41 4341 286 Kampala Email : [email protected] Uganda. Website : www.finance.go.ug THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA In any correspondence on this subject please quote No. ISS 140/255/01 16 Dec 2013 The Clerk to Parliament The Parliament of the Republic of Uganda KAMPALA. SUBMISSION OF UGANDA ROAD FUND ANNUAL REPORT FOR FY 2010/11 In accordance with Section 39 of the Uganda Road Act 2008, this is to submit the Uganda Road Fund Annual performance report for FY 2011/12. The report contains: a) The Audited accounts of the Fund and Auditor General’s report on the accounts of the Fund for FY 2011/12; b) The report on operations of the Fund including achievements and challenges met during the period of reporting. It’s my sincere hope that future reports shall be submitted in time as the organization is now up and running. Maria Kiwanuka MINISTER OF FINANCE, PLANNING AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT cc: The Honourable Minister of Works and Transport cc: The Honourable Minister of Local Government cc: Permanent Secretary/ Secretary to the Treasury cc: Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Works and Transport cc: Permanent Secretary Ministry of Local Government cc: Permanent Secretary Office of the Prime Minister cc: Permanent Secretary Office of the President cc: Chairman Uganda Road Fund Board TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations and Acronyms iii our vision iv -

Annual Report of the Auditor General for the Year Ended 30Th June 2012

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ANNUAL REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2012 VOLUME 2 CENTRAL GOVERNMENT ii 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 REPORT AND OPINION OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE GOVERNMENT OF UGANDA CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE, 2012 ......................................................................................................................... 11 ACCOUNTABILITY SECTOR .......................................................................................... 42 3.0 TREASURY OPERATIONS ................................................................................................ 42 4.0 MINISTRY OF FINANCE, PLANNING AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ..................... 58 5.0 DEPARTMENT OF ETHICS AND INTEGRITY ................................................................ 127 WORKS AND TRANSPORT SECTOR ........................................................................ 131 6.0 MINISTRY OF WORKS AND TRANSPORT .................................................................... 131 7.0 UGANDA NATIONAL ROADS AUTHORITY .................................................................... 165 8.0 THE UGANDA ROAD FUND ............................................................................................ 221 JUSTICE LAW AND ORDER SECTOR ...................................................................... 226 9.0 MINISTRY OF JUSTICE -

Bmau Briefing Paper (15/18) May2018

BMAU BRIEFING PAPER (15/18) MAY 2018 Achievement of the NDPII targets for national roads. Is the Uganda National Roads Authority on track? Overview Key Issues The Government of Uganda (GoU) is implementing i) Budget allocation to the sector has the second National Development Plan (NDP II, persistently fallen short of the NDPII FY2015/16 – FY2019/20). This plan recognises projections. Worse still, not all infrastructure as one of the development appropriated funds are released. fundamentals required to attain middle income status target by 2040. The NDPII has four objectives but ii) More than 100 projects are earmarked the one directly applicable to the roads sub-sector is: under UNRA for implementation within increasing the stock and quality of strategic the NDPII period, but over 60% of the infrastructure to accelerate the country’s these are still at either design and competitiveness. procurement stages, so UNRA is unlikely As a result, a sizeable share of commitments are to achieve the NDPII targets. being directed to infrastructure investments with a iii) Allocations of resources between focus on reducing travel times between regions, new road development projects and integrating the national market and connecting it to maintenance is at a ratio of 80:20% hence other markets in the East African Community. creating a maintenance backlog. This briefing paper assesses the extent to which Uganda National Roads Authority (UNRA) is achieving the national roads NDPII targets over time. Introduction of paved and unpaved roads. The network also comprises of 10 ferries located at The Uganda National Roads Authority strategic points that link national roads (UNRA) aims to develop and maintain a across major water bodies. -

Office of the Auditor General

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ANNUAL REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2014 VOLUME 2 CENTRAL GOVERNMENT ii Table Of Contents List Of Acronyms And Abreviations ................................................................................................ viii 1.0 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Report And Opinion Of The Auditor General On The Government Of Uganda Consolidated Financial Statements For The Year Ended 30th June, 2014 ....................... 38 Accountability Sector................................................................................................................... 55 3.0 Treasury Operations .......................................................................................................... 55 4.0 Ministry Of Finance, Planning And Economic Development ............................................. 62 5.0 Department Of Ethics And Integrity ................................................................................... 87 Works And Transport Sector ...................................................................................................... 90 6.0 Ministry Of Works And Transport ....................................................................................... 90 Justice Law And Order Sector .................................................................................................. 120 7.0 Ministry Of Justice And Constitutional -

Designation of Tax Withholding Agents) Notice, 2018

LEGAL NOTICES SUPPLEMENT No. 7 29th June, 2018. LEGAL NOTICES SUPPLEMENT to The Uganda Gazette No. 33, Volume CXI, dated 29th June, 2018. Printed by UPPC, Entebbe, by Order of the Government. Legal Notice No.12 of 2018. THE VALUE ADDED TAX ACT, CAP. 349. The Value Added Tax (Designation of Tax Withholding Agents) Notice, 2018. (Under section 5(2) of the Value Added Tax Act, Cap. 349) IN EXERCISE of the powers conferred upon the Minister responsible for finance by section 5(2) of the Value Added Tax Act, this Notice is issued this 29th day of June, 2018. 1. Title. This Notice may be cited as the Value Added Tax (Designation of Tax Withholding Agents) Notice, 2018. 2. Commencement. This Notice shall come into force on the 1st day of July, 2018. 3. Designation of persons as tax withholding agents. The persons specified in the Schedule to this Notice are designated as value added tax withholding agents for purposes of section 5(2) of the Value Added Tax Act. 1 SCHEDULE LIST OF DESIGNATED TAX WITHOLDING AGENTS Paragraph 3 DS/N TIN TAXPAYER NAME 1 1002736889 A CHANCE FOR CHILDREN 2 1001837868 A GLOBAL HEALTH CARE PUBLIC FOUNDATION 3 1000025632 A.K. OILS AND FATS (U) LIMITED 4 1000024648 A.K. PLASTICS (U) LTD. 5 1000029802 AAR HEALTH SERVICES (U) LIMITED 6 1000025839 ABACUS PARENTERAL DRUGS LIMITED 7 1000024265 ABC CAPITAL BANK LIMITED 8 1008665988 ABIA MEMORIAL TECHNICAL INSTITUTE 9 1002804430 ABIM HOSPITAL 10 1000059344 ABUBAKER TECHNICAL SERVICES AND GENERAL SUPP 11 1000527788 ACTION AFRICA HELP UGANDA 12 1000042267 ACTION AID INTERNATIONAL -

Roads Sub-Sector Semi-Annual Monitoring Report FY2019/20

ROADS SUB-SECTOR SEMI-ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2019/20 APRIL 2020 Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development P.O. Box 8147, Kampala www.finance.go.ug MOFPED #DoingMore ROADS SUB-SECTOR SEMI-ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2019/20 APRIL 2020 MOFPED #DoingMore TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS ....................................................................................................................................... ii FOREWORD ...................................................................................................................................... iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................. iv CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................1 1.1 Background .................................................................................................................................1 1.1.1 Roads Sub-Sector Mandate ..................................................................................................2 1.1.2 Sub-Sector Objectives and Priorities ....................................................................................2 1.1.3 Sector Financial Performance ...............................................................................................3 CHAPTER 2: METHODOLOGY .....................................................................................................5 2.1 Scope ...........................................................................................................................................5 -

Health Sector Annual Budget Monitoring Report FY2019/20

Health SECtor ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2019/20 NOVEMBER 2020 Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development P.O. Box 8147, Kampala www.finance.go.ug Health Sector : Annual Budget Monitoring Report - FY 2019/20 A HEALTH SECtor ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2019/20 NOVEMBER 2020 Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ............................................................................................... iii FOREWORD ...................................................................................................................................... iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... v CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Background .................................................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER 2: METHODOLOGY ....................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Scope ....................................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 Methodology ................................................................................................................................ 3 2.2.1 Sampling ..................................................................................................................................... -

Our Ref: URF/FIN/REL/KCCA/001/21-22 the Executive Director Kampala Capital City Authority RELEASE of USHS 3,924,192,095 to KCCA

5th Floor, Twed 'lowers o Plot 10, Kafu Road, Nakasero P.O. Box 7501, Kampala, Uganda F: +256(0)414257072/0312178250 ^ 1': +256 (0)414 257071 E: [email protected] 0 W: www.roadfund.ug @ FUND Prudence - Transparency - Integrity - Value Our ref: URF/FIN/REL/KCCA/001/21-22 Date: 22 July 2021 The Executive Director Kampala Capital City Authority P.O Box 7010 Kampala RELEASE OF USHS 3,924,192,095 TO KCCA FOR MAINTENANCE OF KAMPALA CITY ROADS IN QUARTER 1 OF FY 2021/22 The Uganda Road Fund herewith disburses to you funds for financing maintenance of Kampala City roads in Quarter 1 of FY 2021/22 in the amount of UShs 3,924,192,095. The disbursement is made on authority of Board enshrined in Section 14 of the Uganda Road Fund Act 2008. The Q1-2021/22 release has been significantly scaled down due suppression of the budgets for MDAs by upto 41.2% due COVID-19 related challenges as explained in the letter from PS/ST to all Accounting Officers (Ref: MET. 50/268/01 dated 2nd July 2021). The funds released to KCCA constitute 14% of IPF and in accordance with your Qi-FY 2021/22 workplan as per the FY 2021/22 Performance Agreement you executed with the Fund. Details of the Qi FY 2021/22 planned works and expenditure heads as extracted from the Performance Agreement are provided in Table B.i below. Table B.i: Summary Workplan and details of URF Release to KCCA for Qi- FY 2021/22 ACTIVITY Road Maintenance Output KCCA Annual Program / Work plan FY 2021/22 Annual Quantities Quarter 1 workplan Quantity Budget Qty Release (UShs ‘000) (UShs ‘000) Paved Roads -

Baseline Survey of Past and Current Road Sector Research Undertakings

Baseline survey of past and current road sector research undertakings in Uganda and establishment of electronic document management system (EDMS) Inception Report: Institutional review and study methodology e.g Aurecon AMEI Limited AFCAP Project Reference Number. UGA2096A January 2017 Baseline survey of past and current road sector research undertakings in Uganda and establishment of electronic document management system (EDMS) The views in this document are those of the authors and they do not necessarily reflect the views of the Research for Community Access Partnership (ReCAP), or Cardno Emerging Markets (UK) Ltd for whom the document was prepared Cover Photo: Aurecon Quality assurance and review table Version Author(s) Reviewer(s) Date 1 Altus Moolman/ Wynand Steyn/ Nkululeko Leta January 2017 Jane Kamara Les Sampson January 2017 2 Altus Moolman/ Wynand Steyn ReCAP Project Management Unit Cardno Emerging Market (UK) Ltd Oxford House, Oxford Road Thame OX9 2AH United Kingdom Page 2 Baseline survey of past and current road sector research undertakings in Uganda and establishment of electronic document management system (EDMS) Abstract The purpose of this project is to carry out a baseline survey of past and current research that has been undertaken on the roads sector in Uganda, and to establish a databank that enables access to such research. This document presents the Draft Inception Report: Institutional review and study methodology for the study. The study commenced on 22 November 2016. The report documents the methodology; initial feedback from key stakeholders; best practices for establishing an electronic document management system and initial comments on the proposed framework for evaluating historic and current road research. -

Release of Funds for Road Maintenance

22 The New Vision, Monday, March 1, 2010 URF 5th Floor, Soliz House Plot 23, Lumumba Avenue Kampala T: +256 (0)752 229009/0752733323 E: [email protected] W: www.roadfund.ug RELEASE OF FUNDS FOR ROAD MAINTENANCE The Accounting Offi cers of Uganda Road Fund Designated Agencies • Uganda National Roads Authority (UNRA) • All Local Governments RELEASE OF USHS 48,434,573,506/= TO ROAD FUND DESIGNATED AGENCIES FOR MAINTENANCE OF PUBLIC ROADS IN QUARTER 3 OF FY 2009/10 The Uganda Road Fund, inline with powers granted to it under Section 14 of the Uganda Road Fund Act 2008, has authorized the release No Vote District Road Maintenance output in Q3 Amount of Ush 48,434,506 to designated agencies for maintenance of public roads in their respective jurisdictions in Quarter 3 of FY 2009/10. The Routine Periodic Bridges (Shs) release is part of the Ush 116.24 bn appropriated to the Fund by Parliament last July for maintenance of public roads in the second half of (km) (Km) (No) FY 2009/10. The details of the release are contained below in Tables 1 (for Districts and Municipalities) and 2 (for Uganda National Roads Authority) below. B. Release to Designated Municipalities: Votes 752-764 81 751 Arua 1.8 0 0 133,423,693 The releases are based on Quarter 3 workplans that designated agencies submitted to the URF Secretariat in January 2010, summary of 82 752 Entebbe 0 1.2 0 208,414,064 which is provided in the two tables. 83 753 Fort Portal 1.2 0 0 120,508,184 Table 1: Releases to Local Governments for the Third Quarter FY 2009/10 84 754 Gulu - - - 0 85 755 Jinja 0 2.46 0 95,074,620 No Vote District Road Maintenance output in Q3 Amount 86 757 Kabale 3.3 0 0 110,428,642 Routine Periodic Bridges (Shs) 87 758 Lira 2.15 0 0 182,697,599 (km) (Km) (No) 88 759 Masaka 0 3.91 0 132,564,232 A. -

Health Sector ANNUAL MONITORING REPORT Financial Year 2014/15

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Health Sector ANNUAL MONITORING REPORT Financial Year 2014/15 October 2015 Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development P.O.Box 8147, Kampala www.finance.go.ug THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA HEALTH SECTOR ANNUAL MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2014/15 October 2015 Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development P. O. Box 8147 Kampala www.finance.go.ug TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ..................................................................................................... 1 FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................................ 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY........................................................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 6 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................................. 6 1.2 Rationale for the report ....................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Report outline ........................................................................................................................................ 7 CHAPTER 2: METHODOLOGY ..............................................................................................................