"Too Long Neglected"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 Annual Report

Office of Navajo Nation Scholarship & Financial Assistance 2013 Annual Report Inside 2 Data & Statistics 2013 Statistical Profile Types of Student Funding 4 Funding Sources Federal Navajo Nation Trust Funds Corporate 7 Funding Activity Summary of Funds Expended by Agencies 10 Student Performance Degrees Sought Decreases in Funding Underscore Need for Prudent Use By Award Recipients By Rose Graham ABOVE Six students named Chief Manuelito Scholars in 18 Chief Manuelito Scholars Department Director 2013 gained admission to Stanford University. (L-R) Emily Walck, Ashley Manuelito, Taryn Harvey and Taylor Billey. 110 Students Earn the A four-year college degree has probably never Not shown: Katelyn McKown and Isabella Robbins. Photo Nation’s Top Scholarship been more valuable. In 2013, college graduates courtesy of Eugene R. Begay made 98 percent more an hour on average than people without a degree according to data re- The ONNSFA also owes much gratitude to leased by the U.S. Dept. of Labor. Navajo Nation leaders. In 2013, the Nation’s contri- Apply online at: Meanwhile, the cost of a college education bution to the scholarship fund greatly increased. continues to rise and so does the demand for Revenues from Navajo Nation sales taxes pro- www.onnsfa.org scholarships. vided an additional $3 million and the Nation’s set Since 2010, the Office of Navajo Nation Schol- aside from General Funds increased by $2 million. Chinle Agency Office arship & Financial Assistance has received more There is still a real need for additional resourc- (800) 919-9269 than 17,000 applications each year. More than half es. -

Captain Benteen's Two Views of the Reno Valley Fight

Captain Benteen’s Two Views of Indians there engaged in demolishing about 13 men as I thought on the skirmish line.”5 the Reno Valley Fight Second view is Benteen’s letter to his wife July 4. By Gerry Schultz “My Darling,” … “When getting on top of hill so that th On the 25 of June, 1876, the U.S. Seventh Cavalry the village could be seen – I saw an immense number crossed the divide of the Wolf Mountains and of Indians on the plain – mounted of course and descended into the valley of the Little Bighorn. The charging down on some dismounted men of Reno’s Army followed a tributary, Ash Creek that flowed to command; the balance of R’s command were the Little Bighorn River. mounted, and flying for dear life to the bluffs on the same side of river that I was.”6 Captain Benteen and his battalion of three Companies H, D, and K, were ordered to the left of General The following is written close to chronological order, Custer, on a valley hunt. Benteen described his forming an event-timeline. Certain events need to orders, “to proceed out into a line of bluffs about 4 or take place in advance, leading up to Captain 1 5 miles away, to pitch into anything I came across.” Benteen’s two views of Major Reno’s valley fight. Captain Benteen’s battalion moved south of Ash creek, separating from General Custer’s and Major Events leading up to Benteen’s RCOI View Reno’s battalions. These events take place to set the stage: General Custer with five companies and Major Reno Major Reno received orders to cross the Little with three companies, continued down Ash Creek to Bighorn and strike the village. -

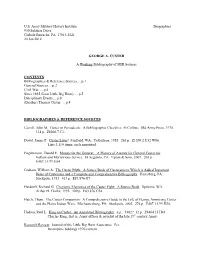

Custer, George.Pdf

U.S. Army Military History Institute Biographies 950 Soldiers Drive Carlisle Barracks, PA 17013-5021 20 Jan 2012 GEORGE A. CUSTER A Working Bibliography of MHI Sources CONTENTS Bibliographies & Reference Sources.....p.1 General Sources.....p.2 Civil War…..p.4 Since 1865 (Less Little Big Horn)…..p.5 Disciplinary Events.....p.8 (Brother) Thomas Custer…..p.8 BIBLIOGRAPHIES & REFERENCE SOURCES Carroll, John M. Custer in Periodicals: A Bibliographic Checklist. Ft Collins: Old Army Press, 1975. 134 p. Z8206.7.C3. Dowd, James P. Custer Lives! Fairfield, WA: YeGalleon, 1982. 263 p. Z1209.2.U52.W86. Lists 3,114 items, each annotated. Engebretson, Darold E. Medals for the General: A History of Awards for General Custer for Gallant and Meritorious Service. El Segundo, CA: Upton & Sons, 2007. 203 p. E467.1.C99.E54. Graham, William A. The Custer Myth: A Source Book of Custerania to Which is Added Important Items of Custerania and a Complete and Comprehensive Bibliography. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole, 1953. 413 p. E83.876.G7. Hardorff, Richard G. Cheyenne Memories of the Custer Fight: A Source Book. Spokane, WA: Arthur H. Clarke, 1995. 189 p. E83.876.C54. Hatch, Thom. The Custer Companion: A Comprehensive Guide to the Life of George Armstrong Custer and the Plains Indian Wars. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole, 2002. 274 p. E467.1.C99.H38. Hedren, Paul L. King on Custer: An Annotated Bibliography. n.p., 1982? 12 p. Z8464.35.H43. Charles King, that is, Army officer & novelist of the late 19th century Army. Research Review. Journal of the Little Big Horn Associates. Per. -

CUSTER BATTLEFIELD National Monument Montana (Now Little Bighorn Battlefield)

CUSTER BATTLEFIELD National Monument Montana (now Little Bighorn Battlefield) by Robert M. Utley National Park Service Historical Handbook Series No. 1 Washington, D.C. 1969 Contents a. A CUSTER PROFILE b. CUSTER'S LAST STAND 1. Campaign of 1876 2. Indian Movements 3. Plan of Action 4. March to the Little Bighorn 5. Reno Attacks 6. The Annihilation of Custer 7. Reno Besieged 8. Rescue 9. Collapse of the Sioux 10. Custer Battlefield Today 11. Campaign Maps c. APPENDIXES I. Officers of the 7th Cavalry at the Battle of the Little Bighorn II. Low Dog's Account of the Battle III. Gall's Account of the Battle IV. A Participant's Account of Major Reno's Battle d. CUSTER'S LAST CAMPAIGN: A PHOTOGRAPHIC ESSAY e. THE ART AND THE ARTIST f. ADMINISTRATION For additional information, visit the Web site for Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument or view their Official National Park Handbook (#132): Historical Handbook Number One 1969 The publication of this handbook was made possible by a grant from the Custer Battlefield Historical and Museum Association, Inc. This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archeological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402. Price lists of Park Service publications sold by the Government Printing Office may be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D.C. 20402. The National Park System, of which Custer Battlefield National Monument is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and enjoyment of its people. -

Legends of the West

1 This novel is dedicated to Vivian Towlerton For the memories of good times past 2 This novel was written mostly during the year 2010 CE whilst drinking the fair-trade coffee provided by the Caffé Vita and Sizizis coffee shops in Olympia, Washington Most of the research was conducted during the year 2010 CE upon the free Wi-Fi provided by the Caffé Vita and Sizizis coffee shops in Olympia, Washington. My thanks to management and staff. It was good. 3 Excerpt from Legends of the West: Spotted Tail said, “Now, let me tell you the worst thing about the Wasicu, and the hardest thing to understand: They do not understand choice...” This caused a murmur of consternation among the Lakota. Choice was choice. What was not there to not understand? Choice is the bedrock tenet of our very view of reality. The choices a person makes are quite literally what makes that person into who they are. Who else can tell you how to be you? One follows one’s own nature and one’s own inner voice; to us this is sacrosanct. You can choose between what makes life beautiful and what makes life ugly; you can choose whether to paint yourself in a certain manner or whether to wear something made of iron — or, as was the case with the famous Cheyenne warrior Roman Nose — you could choose to never so much as touch iron. In battle you choose whether you should charge the enemy first, join the main thrust of attack, or take off on your own and try to steal his horses. -

Fort Laramie Park History, 1834 – 1977

Fort Laramie NHS: Park History Fort Laramie Park History, 1834-1977 FORT LARAMIE PARK HISTORY 1834-1977 by Merrill J. Mattes September 1980 Rocky Mountain Regional Office National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior TABLE OF CONTENTS fola/history/index.htm Last Updated: 01-Mar-2003 file:///C|/Web/FOLA/history/index.htm [9/7/2007 12:41:47 PM] Fort Laramie NHS: Park History Fort Laramie Park History, 1834-1977 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Author's Preface Part I. FORT LARAMIE, 1834 - 1890 I Introduction II Fur Trappers Discover the Oregon Trail III Fort William, the First Fort Laramie IV Fort John, the Second Fort Laramie V Early Migrations to Oregon and Utah VI Fort Laramie, the U.S. Army, and the Forty-Niners VII The Great California Gold Rush VIII The Indian Problem: Treaty and Massacre IX Overland Transportation and Communications X Uprising of the Sioux and Cheyenne XI Red Cloud's War XII Black Hills Gold and the Sioux Campaigns XIII The Cheyenne-Deadwood Stage Road XIV Decline and Abandonment XV Evolution of the Military Post XVI Fort Laramie as Country Village and Historic Ruin Part II. THE CRUSADE TO SAVE FORT LARAMIE I The Crusade to Save Fort Laramie Footnotes to Part II file:///C|/Web/FOLA/history/contents.htm (1 of 2) [9/7/2007 12:41:48 PM] Fort Laramie NHS: Park History Part III. THE RESTORATION OF FORT LARAMIE 1. Interim State Custodianship 1937-1938 - Greenburg, Rymill and Randels 2. Early Federal Custodianship 1938-1939 - Mattes, Canfield, Humberger and Fraser 3. -

Jewel Cave National Monument Historic Resource Study

PLACE OF PASSAGES: JEWEL CAVE NATIONAL MONUMENT HISTORIC RESOURCE STUDY 2006 by Gail Evans-Hatch and Michael Evans-Hatch Evans-Hatch & Associates Published by Midwestern Region National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska _________________________________ i _________________________________ ii _________________________________ iii _________________________________ iv Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1: First Residents 7 Introduction Paleo-Indian Archaic Protohistoric Europeans Rock Art Lakota Lakota Spiritual Connection to the Black Hills Chapter 2: Exploration and Gold Discovery 33 Introduction The First Europeans United States Exploration The Lure of Gold Gold Attracts Euro-Americans to Sioux Land Creation of the Great Sioux Reservation Pressure Mounts for Euro-American Entry Economic Depression Heightens Clamor for Gold Custer’s 1874 Expedition Gordon Party & Gold-Seekers Arrive in Black Hills Chapter 3: Euro-Americans Come To Stay: Indians Dispossessed 59 Introduction Prospector Felix Michaud Arrives in the Black Hills Birth of Custer and Other Mining Camps Negotiating a New Treaty with the Sioux Gold Rush Bust Social and Cultural Landscape of Custer City and County Geographic Patterns of Early Mining Settlements Roads into the Black Hills Chapter 4: Establishing Roots: Harvesting Resources 93 Introduction Milling Lumber for Homes, Mines, and Farms Farming Railroads Arrive in the Black Hills Fluctuating Cycles in Agriculture Ranching Rancher Felix Michaud Harvesting Timber Fires in the Forest Landscapes of Diversifying Uses _________________________________ v Chapter 5: Jewel Cave: Discovery and Development 117 Introduction Conservation Policies Reach the Black Hills Jewel Cave Discovered Jewel Cave Development The Legal Environment Developing Jewel Cave to Attract Visitors The Wind Cave Example Michauds’ Continued Struggle Chapter 6: Jewel Cave Under the U.S. -

Margaret Custer Calhoun

University of Oklahoma College of Law University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 4-29-1896 Margaret Custer Calhoun. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/indianserialset Part of the Indigenous, Indian, and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation H.R. Rep. No. 2677, 54th Cong., 2nd Sess. (1896) This House Report is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 by an authorized administrator of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 54TH CONGRESS, t ROUSE OF H,EPRESENTATIVES. ) REPORT 2d Session. J l No. 2Gi"7. MARGARET CUSTER CALHOUN. JANUARY 28, 1897.-Committed to the Committee of the Whole Honse and ordered to · be printed. Mr. LOUDENSLAGER, from the Committee on Pensions, submitted the following REPORT. rro accompany s. 2954.] The Committee on Pensions, to whom was referred the bill. (S. 2954) gTanting an increase of pension to Margaret Custer·Calhoun, have con sidered the same, and respectfully report as follows: Said bill is accompanied by Senate Report No. 813, this term, and the same, fully setting forth the facts, is adopted by your committee as their report, and the bill is returned with a favorable recommendation. [Senate Report No. 813, Fifty-fourth Congress, fir.st session.) The Committee on Pensions, to whom was referred the bill (S. -

February 2014

GaryGary InterInter StateState Established Sept. 6, 1878; the only newspaper in the world solely interested in the welfare of Gary, SD and vicinity. Gary Historical Association 2014 A monthly newspaper with news of the past and present. www.experiencegarysd.com "The opinions in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Gary Historical Association.” This paper printed for you by DNB NATIONAL BANK Gary and Clear Lake SD We want to thank them for this service! Gary 605.272.5233 Clear Lake 605.874.2191 Gary, the oldest town in the county, was Dakota’s Rapid Growth. The growth of this Territory during this past year is something phe- founded in 1877 by the Winona & St. Peter Rail- nomenal . Our population has increased at the rate road Company, thought the railroad had reached of 12,000 a month, since January last. The larger that point in the fall of 1872. Gary was originally half of this increase settled in the southern half of the Territory. Post offices have been established at called State Line because of its location on the the rapid rate of 12 a month for the past 11 months. boundary line; then for a time it was called Head- Now we are a prosperous, growing and enterprising quarters, because it was the base of operations for commonwealth with a population numbering 275,00 souls; with a voting strength of 60,000; the Colonel DeGraff, the railroad contractor. advantages of Dakota over all competitors is af- An attempt was made to have it named DeGraff, firmed by over one hundred newspapers; we have but there was another town by that name on the St. -

3. Striden Vid Rosebud Creek

STRIDEN VID LITTLE BIGHORN 1876 TAKTISK BLUNDER ELLER OTUR en kort analys Bertil Thörn INDIANKLUBBEN en E-bok från INDIANKLUBBEN alla rättigheter förbehålles delar får dock kopieras om källan tydligt anges Omslagsbilden är en oljemålning kallad: ”Custer’s Last Stand” Den är utförd 1986 av Mort Künstler För Mort Künstlers hemsida se : http://www.mortkunstler.com/ en produktion från INDIANKLUBBEN i Sverige Helsingborg, 2014; utgåva 2 2 LLIITTTTLLEE BBIIGGHHOORRNN 11887766 TAKTISK BLUNDER ELLER OTUR EN KORT ANALYS * * * av Bertil Thörn INDIANKLUBBEN Helsingborg 2014 3 Kapten George Kaiser Sanderson, (1844 - 1893); 11th US Infantry, tillsammans med en oidentifierad soldat vid kapten Myles Keogh’s grav på slagfältet i samband med den första ombegravningen, 1879 Foto: Stanley J. Morrow 4 Söndagen den 25 juni 1876 utspelade sig ett drama som fick en våldsam upplösning på en trädlös grässluttning långt borta i USAs ödemark. En då helt okänd ödemark som idag är en del av staten Montanas sydöstra hörn. Invid en flod som av indianerna kallades Gre- asy Grass och som på dagens kartor har namnet Little Bighorn River, möttes en ame- rikansk arméenhet ur Sjunde Kavallerirege- mentet och en stor grupp indianer ur stam- marna Sioux, Cheyenne och Arapaho. Den påföljande striden har gått till historien som "Striden vid Little Bighorn", eller som "Custer's Last Stand". Idag är platsen ett ”National Monument” och besöks årligen av hundratusentals besökare. 5 innehållsförteckning Del 1 kap kapitelrubrik sida 1 Förutsättningen 07 2 Armén tar över 9 3 Drabbningen vid Rosebud Creek 12 4 Indianernas förehavande 14 5 Dakotakolonnens uppmarsch 17 6 Custer släpps loss 21 7 Angreppsstyrkans uppmarsch 24 8 Avgörande beslut 28 9 Crows Nest 31 10 Över vattendelaren 35 11 Framryckningen 39 12 Reno får sina order 43 13 Custers nästa drag 46 14 Reno öppnar striden 48 15 Renos reträtt 50 16 Custer på höjderna 54 17 Benteens agerande 56 18 Custers avancemang 59 19 Custers strider 62 20 Slutet 66 21 Belägringen av Reno 71 22 Räddningen 75 Forts. -

Little Bighorn Estate 2005 HAKO

HAKOMAGAZINE 33 Little Bighorn estate 2005 HAKO Incontri con le culture dell’america indigena Sommario estate 2005 4 . Intenti 5 . Editoriale 7 . Nuvole che indugiano sul Greasy Grass 21. La scacchiera Little Bighorn 24. Scheda: i protagonisti 27. La battaglia di Little Bighorn 37. Hokahey! Questo è un buon giorno per morire 45. Tieni l’ultima pallotto- la per te 47. Lupi per i soldati bian- chi 49. Una strada che ci è ignota 51. Scheda 53. E Capelli Lunghi giace qui sul crinale 55. Custer’s Last Stand 59. Le scogliere dell’alterità 63. Oggi è un buon giorno per rivivere Prossimamente Ecologia e tradizioni: Sopra: “Custer’s Last Stand” (L’ultima resistenza di Custer) di Edgar S. Paxton (1899). Per il caso dei Makah ottenere questa tela di 2 metri per 3 e 1/2 il pittore lavorò otto anni; la tela è conservata alla Whitney Gallery of Western Art, Cody, Wo. In copertina: Il fiume Little Bighorn (Greasy Grass o Erba Unta per gli indiani) con l’Indian Corrispondenza: Memorial e Slow Bull, oglala lakota, 1907, di E. S. Curtis. Hako - via N. Tommaseo 24- 35131 In retro di copertina: Crazy Horse a Little Bighorn in un quadro western. Padova Abbonamenti c. c. postale n° 15557358 intestato a Sandra Busatta - via N. Tommaseo 24 - 35131 Padova. Annuale (3 numeri): euro 20,00; Sostenitore: euro 26,00 e-mail: [email protected] Direttore responsabile: Marco Crimi http://www.hakomagazine.net Redazione: Sandra e Flavia Busatta Elaborazione digitale: Lucas Cranach Stampato in proprio Autorizzazione Tribunale di Padova n. 1542 del 28.2.1995 3 Little Big Horn estate 2005 “Danza della vittoria”. -

Shaping America with General George A. Custer

u History Lesson u GeneralShaping Ge AmericaOrGe a. with Custer General Custer’s faithful Morgan Dandy was an unfailing member of the company. By Brenda L. tippin ne of the most colorful characters of early American Custer’s early life history is the famous General, George Custer, best A native of New Rumley, Ohio, George Armstrong Custer was remembered for The Battle of Little Big Horn, in born December 5, 1839 to Emmanuel H. Custer, a blacksmith which he and his men met a gruesome fate at the and farmer who had been widowed, and his second wife, Maria Ohands of the Sioux and other tribes gathered under Sitting Bull. A Ward, also widowed. Custer was the oldest of three brothers born strong personality, loved by many, criticized by others, controversy to this union, Nevin, Thomas, and Boston, and the youngest child still rages to this day regarding Custer and his last fight. History has was a sister, Margaret. They were plain people and hard-working often portrayed Custer as an arrogant man whose poor judgment farmers, instilling in George early on strong principles of right and was to blame for this major disaster. Many remember the horse wrong, honesty, fairness, and a keen sense of responsibility. George Comanche, a Morgan, as the lone survivor of that battle. Comanche was of a gentle nature, always full of fun, and loved practical jokes. was in fact owned by Captain Myles Keogh of Custer’s regiment. It He was called “Autie” as a child, and from his earliest life all he ever is less known that Custer himself rode several Morgans during the wanted was to be a soldier.