Monitoring the Carbon Footprint of Dry Bulk Shipping in the EU: an Early Assessment of the MRV Regulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China's Merchant Marine

“China’s Merchant Marine” A paper for the China as “Maritime Power” Conference July 28-29, 2015 CNA Conference Facility Arlington, Virginia by Dennis J. Blasko1 Introductory Note: The Central Intelligence Agency’s World Factbook defines “merchant marine” as “all ships engaged in the carriage of goods; or all commercial vessels (as opposed to all nonmilitary ships), which excludes tugs, fishing vessels, offshore oil rigs, etc.”2 At the end of 2014, the world’s merchant ship fleet consisted of over 89,000 ships.3 According to the BBC: Under international law, every merchant ship must be registered with a country, known as its flag state. That country has jurisdiction over the vessel and is responsible for inspecting that it is safe to sail and to check on the crew’s working conditions. Open registries, sometimes referred to pejoratively as flags of convenience, have been contentious from the start.4 1 Dennis J. Blasko, Lieutenant Colonel, U.S. Army (Retired), a Senior Research Fellow with CNA’s China Studies division, is a former U.S. army attaché to Beijing and Hong Kong and author of The Chinese Army Today (Routledge, 2006).The author wishes to express his sincere thanks and appreciation to Rear Admiral Michael McDevitt, U.S. Navy (Ret), for his guidance and patience in the preparation and presentation of this paper. 2 Central Intelligence Agency, “Country Comparison: Merchant Marine,” The World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2108.html. According to the Factbook, “DWT or dead weight tonnage is the total weight of cargo, plus bunkers, stores, etc., that a ship can carry when immersed to the appropriate load line. -

TOP Tankers Inc

TOP Tankers Inc. October 2005 NASDAQ: “TOPT” Page 1 Disclaimer Forward-Looking Statements This presentation contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of applicable federal securities laws. Such statements are based upon current expectations that involve risks and uncertainties. Any statements contained herein that are not statements of historical fact may be deemed to be forward-looking statements. For example, words such as “may,” “will,” “should,” “estimates,” “predicts,” “potential,” “continue,” “strategy,” “believes,” “anticipates,” “plans,” “expects,” “intends” and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements. Actual results and the timing of certain events may differ significantly from the results discussed or implied in the forward-looking statements. Among the factors that might cause or contribute to such a discrepancy include, but are not limited to, the risk factors described in the Company’s Registration Statement filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission, particularly those describing variations on charter rates and their effect on the Company’s revenues, net income and profitability as well as the value of the Company’s fleet. Page 2 Evangelos J. Pistiolis, Chief Executive Officer Page 3 Founder & Continued Equity Sponsorship Dynamic Founder & Continued Equity Sponsorship Entered shipping business in 1992, tankers in 1999 July 2004, $135.1m IPO acquired 2 DH Suezmax and 8 DH Handymax tankers November 2004, $148.1m follow-on, acquired 5 DH Suezmax tankers 2005, Organic Growth: -

International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969

No. 21264 MULTILATERAL International Convention on tonnage measurement of ships, 1969 (with annexes, official translations of the Convention in the Russian and Spanish languages and Final Act of the Conference). Concluded at London on 23 June 1969 Authentic texts: English and French. Authentic texts of the Final Act: English, French, Russian and Spanish. Registered by the International Maritime Organization on 28 September 1982. MULTILAT RAL Convention internationale de 1969 sur le jaugeage des navires (avec annexes, traductions officielles de la Convention en russe et en espagnol et Acte final de la Conf rence). Conclue Londres le 23 juin 1969 Textes authentiques : anglais et fran ais. Textes authentiques de l©Acte final: anglais, fran ais, russe et espagnol. Enregistr e par l©Organisation maritime internationale le 28 septembre 1982. Vol. 1291, 1-21264 4_____ United Nations — Treaty Series Nations Unies — Recueil des TVait s 1982 INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION © ON TONNAGE MEASURE MENT OF SHIPS, 1969 The Contracting Governments, Desiring to establish uniform principles and rules with respect to the determination of tonnage of ships engaged on international voyages; Considering that this end may best be achieved by the conclusion of a Convention; Have agreed as follows: Article 1. GENERAL OBLIGATION UNDER THE CONVENTION The Contracting Governments undertake to give effect to the provisions of the present Convention and the annexes hereto which shall constitute an integral part of the present Convention. Every reference to the present Convention constitutes at the same time a reference to the annexes. Article 2. DEFINITIONS For the purpose of the present Convention, unless expressly provided otherwise: (1) "Regulations" means the Regulations annexed to the present Convention; (2) "Administration" means the Government of the State whose flag the ship is flying; (3) "International voyage" means a sea voyage from a country to which the present Convention applies to a port outside such country, or conversely. -

International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969

Page 1 of 47 Lloyd’s Register Rulefinder 2005 – Version 9.4 Tonnage - International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969 Tonnage - International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969 Copyright 2005 Lloyd's Register or International Maritime Organization. All rights reserved. Lloyd's Register, its affiliates and subsidiaries and their respective officers, employees or agents are, individually and collectively, referred to in this clause as the 'Lloyd's Register Group'. The Lloyd's Register Group assumes no responsibility and shall not be liable to any person for any loss, damage or expense caused by reliance on the information or advice in this document or howsoever provided, unless that person has signed a contract with the relevant Lloyd's Register Group entity for the provision of this information or advice and in that case any responsibility or liability is exclusively on the terms and conditions set out in that contract. file://C:\Documents and Settings\M.Ventura\Local Settings\Temp\~hh4CFD.htm 2009-09-22 Page 2 of 47 Lloyd’s Register Rulefinder 2005 – Version 9.4 Tonnage - International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969 - Articles of the International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships Articles of the International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships Copyright 2005 Lloyd's Register or International Maritime Organization. All rights reserved. Lloyd's Register, its affiliates and subsidiaries and their respective officers, employees or agents are, individually and collectively, referred to in this clause as the 'Lloyd's Register Group'. The Lloyd's Register Group assumes no responsibility and shall not be liable to any person for any loss, damage or expense caused by reliance on the information or advice in this document or howsoever provided, unless that person has signed a contract with the relevant Lloyd's Register Group entity for the provision of this information or advice and in that case any responsibility or liability is exclusively on the terms and conditions set out in that contract. -

Shipbuilding

Shipbuilding A promising rst half, an uncertain second one 2018 started briskly in the wake of 2017. In the rst half of the year, newbuilding orders were placed at a rate of about 10m dwt per month. However the pace dropped in the second half, as owners grappled with a rise in newbuilding prices and growing uncertainty over the IMO 2020 deadline. Regardless, newbuilding orders rose to 95.5m dwt in 2018 versus 83.1m dwt in 2017. Demand for bulkers, container carriers and specialised ships increased, while for tankers it receded, re ecting low freight rates and poor sentiment. Thanks to this additional demand, shipbuilders succeeded in raising newbuilding prices by about 10%. This enabled them to pass on some of the additional building costs resulting from higher steel prices, new regulations and increased pressure from marine suppliers, who have also been struggling since 2008. VIIKKI LNG-fuelled forest product carrier, 25,600 dwt (B.Delta 25), built in 2018 by China’s Jinling for Finland’s ESL Shipping. 5 Orders Million dwt 300 250 200 150 100 50 SHIPBUILDING SHIPBUILDING KEY POINTS OF 2018 KEY POINTS OF 2018 0 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Deliveries vs demolitions Fleet evolution Deliveries Demolitions Fleet KEY POINTS OF 2018 Summary 2017 2018 Million dwt Million dwt Million dwt Million dwt Ships 1,000 1,245 Orders 200 2,000 m dwt 83.1 95.5 180 The three Asian shipbuilding giants, representing almost 95% of the global 1,800 orderbook by deadweight, continued to ght ercely for market share. -

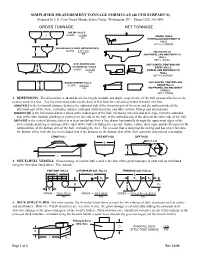

SIMPLIFIED MEASUREMENT TONNAGE FORMULAS (46 CFR SUBPART E) Prepared by U.S

SIMPLIFIED MEASUREMENT TONNAGE FORMULAS (46 CFR SUBPART E) Prepared by U.S. Coast Guard Marine Safety Center, Washington, DC Phone (202) 366-6441 GROSS TONNAGE NET TONNAGE SAILING HULLS D GROSS = 0.5 LBD SAILING HULLS 100 (PROPELLING MACHINERY IN HULL) NET = 0.9 GROSS SAILING HULLS (KEEL INCLUDED IN D) D GROSS = 0.375 LBD SAILING HULLS 100 (NO PROPELLING MACHINERY IN HULL) NET = GROSS SHIP-SHAPED AND SHIP-SHAPED, PONTOON AND CYLINDRICAL HULLS D D BARGE HULLS GROSS = 0.67 LBD (PROPELLING MACHINERY IN 100 HULL) NET = 0.8 GROSS BARGE-SHAPED HULLS SHIP-SHAPED, PONTOON AND D GROSS = 0.84 LBD BARGE HULLS 100 (NO PROPELLING MACHINERY IN HULL) NET = GROSS 1. DIMENSIONS. The dimensions, L, B and D, are the length, breadth and depth, respectively, of the hull measured in feet to the nearest tenth of a foot. See the conversion table on the back of this form for converting inches to tenths of a foot. LENGTH (L) is the horizontal distance between the outboard side of the foremost part of the stem and the outboard side of the aftermost part of the stern, excluding rudders, outboard motor brackets, and other similar fittings and attachments. BREADTH (B) is the horizontal distance taken at the widest part of the hull, excluding rub rails and deck caps, from the outboard side of the skin (outside planking or plating) on one side of the hull, to the outboard side of the skin on the other side of the hull. DEPTH (D) is the vertical distance taken at or near amidships from a line drawn horizontally through the uppermost edges of the skin (outside planking or plating) at the sides of the hull (excluding the cap rail, trunks, cabins, deck caps, and deckhouses) to the outboard face of the bottom skin of the hull, excluding the keel. -

Dictionary.Pdf

THE SEAFARER’S WORD A Maritime Dictionary A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Ranger Hope © 2007- All rights reserved A ● ▬ A: Code flag; Diver below, keep well clear at slow speed. Aa.: Always afloat. Aaaa.: Always accessible - always afloat. A flag + three Code flags; Azimuth or bearing. numerals: Aback: When a wind hits the front of the sails forcing the vessel astern. Abaft: Toward the stern. Abaft of the beam: Bearings over the beam to the stern, the ships after sections. Abandon: To jettison cargo. Abandon ship: To forsake a vessel in favour of the life rafts, life boats. Abate: Diminish, stop. Able bodied seaman: Certificated and experienced seaman, called an AB. Abeam: On the side of the vessel, amidships or at right angles. Aboard: Within or on the vessel. About, go: To manoeuvre to the opposite sailing tack. Above board: Genuine. Able bodied seaman: Advanced deckhand ranked above ordinary seaman. Abreast: Alongside. Side by side Abrid: A plate reinforcing the top of a drilled hole that accepts a pintle. Abrolhos: A violent wind blowing off the South East Brazilian coast between May and August. A.B.S.: American Bureau of Shipping classification society. Able bodied seaman Absorption: The dissipation of energy in the medium through which the energy passes, which is one cause of radio wave attenuation. Abt.: About Abyss: A deep chasm. Abyssal, abysmal: The greatest depth of the ocean Abyssal gap: A narrow break in a sea floor rise or between two abyssal plains. -

Scorpio Tankers Inc. Company Presentation June 2018

Scorpio Tankers Inc. Company Presentation June 2018 1 1 Company Overview Key Facts Fleet Profile Scorpio Tankers Inc. is the world’s largest and Owned TC/BB Chartered-In youngest product tanker company 60 • Pure product tanker play offering all asset classes • 109 owned ECO product tankers on the 50 water with an average age of 2.8 years 8 • 17 time/bareboat charters-in vessels 40 • NYSE-compliant governance and transparency, 2 listed under the ticker “STNG” • Headquartered in Monaco, incorporated in the 30 Marshall Islands and is not subject to US income tax 45 20 38 • Vessels employed in well-established Scorpio 7 pools with a track record of outperforming the market 10 14 • Merged with Navig8 Product Tankers, acquiring 27 12 ECO-spec product tankers 0 Handymax MR LR1 LR2 2 2 Company Profile Shareholders # Holder Ownership 1 Dimensional Fund Advisors 6.6% 2 Wellington Management Company 5.9% 3 Scorpio Services Holding Limited 4.5% 4 Magallanes Value Investor 4.1% 5 Bestinver Gestión 4.0% 6 BlackRock Fund Advisors 3.3% 7 Fidelity Management & Research Company 3.0% 8 Hosking Partners 3.0% 9 BNY Mellon Asset Management 3.0% 10 Monarch Alternative Capital 2.8% Market Cap ($m) Liquidity Per Day ($m pd) $1,500 $12 $10 $1,000 $8 $6 $500 $4 $2 $0 $0 Euronav Frontline Scorpio DHT Gener8 NAT Ardmore Scorpio Frontline Euronav NAT DHT Gener8 Ardmore Tankers Tankers Source: Fearnleys June 8th, 2018 3 3 Product Tankers in the Oil Supply Chain • Crude Tankers provide the marine transportation of the crude oil to the refineries. -

Determirjiation of the Compensated Gross Tonnage Factors for Superyachts

International Shipbuilding Progress 57 (2010) 127-146 127 DOI 10.3233/ISP-2010-0066 lOS Press Determirjiation of the Compensated Gross Tonnage factors for superyachts Jeroen FJ. Pruyn Robert G. Helckenberg ^ and Chris M. van Hooren^ ^ Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands ^ Supeiyacht Builders Association, Delft, The Netherlands In order to provide the basis for a fair comparison, an indicator was developed to measure the amount of work that goes into the construction of a vessel. The foundation for this Compensated Gross Tonnage was laid in the 1970s by the OECD to compensate for the differences in work involved in producing a gross ton (GT) of ship in different sizes and types. Since 2007, the CGT of a vessel of a certain type as a function of its size (measured in GT) has been expressed as CGT = A x GT-®. However, no interna tionally accepted A and B values exist to convert superyachts from GT to CGT. The superyacht building industry believes that this omission results in an under appreciation of the importance of the sector. This paper describes the research carried out into this subject and confirms that the cuiTent assignments for su peryachts greatly under appreciate the value of the sector. Based on the current data, the most appropriate values for superyachts are 278 for A and 0.58 for B. The spread is quite large and more data would help confirm this finding. Keywords: CGT, superyachts, shipbuilding 1. Background: CGT factors To compare the output of shipyards and shipbuilding industries using the size of delivered vessels (e.g., in terms of Gross Tonnage) alone is insufficient: how does one compare a (very large) crude oil tanker to a (smaller but much more complex) passenger ship? In order to provide the foundation for a fair comparison, an indicator was de veloped to measure the amount of work that goes into the construction of a ves sel: Compensated Gross Tonnage. -

Measurement of Fishing

35 Rapp. P.-v. Réun. Cons. int. Explor. Mer, 168: 35-38. Janvier 1975. TONNAGE CERTIFICATE DATA AS FISHING POWER PARAMETERS F. d e B e e r Netherlands Institute for Fishery Investigations, IJmuiden, Netherlands INTRODUCTION London, June 1969 — An entirely new system of The international exchange of information about measuring the gross and net fishing vessels and the increasing scientific approach tonnage was set up called the to fisheries in general requires the use of a number of “International Convention on parameters of which there is a great variety especially Tonnage Measurement of in the field of main dimensions, coefficients, propulsion Ships, 1969” .1 data (horse power, propeller, etc.) and other partic ulars of fishing vessels. This variety is very often caused Every ship which has been measured and marked by different historical developments in different in accordance with the Convention concluded in Oslo, countries. 1947, is issued with a tonnage certificate called the The tonnage certificate is often used as an easy and “International Tonnage Certificate”. The tonnage of official source for parameters. However, though this a vessel consists of its gross tonnage and net tonnage. certificate is an official one and is based on Inter In this paper only the gross tonnage is discussed national Conventions its value for scientific purposes because net tonnage is not often used as a parameter. is questionable. The gross tonnage of a vessel, expressed in cubic meters and register tons (of 2-83 m3), is defined as the sum of all the enclosed spaces. INTERNATIONAL REGULATIONS ON TONNAGE These are: MEASUREMENT space below tonnage deck trunks International procedures for measuring the tonnage tweendeck space round houses of ships were laid down as follows : enclosed forecastle excess of hatchways bridge spaces spaces above the upper- Geneva, June 1939 - International regulations for break(s) deck included as part of tonnage measurement of ships poop the propelling machinery were issued through the League space. -

Branch's Elements of Shipping/Alan E

‘I would strongly recommend this book to anyone who is interested in shipping or taking a course where shipping is an important element, for example, chartering and broking, maritime transport, exporting and importing, ship management, and international trade. Using an approach of simple analysis and pragmatism, the book provides clear explanations of the basic elements of ship operations and commercial, legal, economic, technical, managerial, logistical, and financial aspects of shipping.’ Dr Jiangang Fei, National Centre for Ports & Shipping, Australian Maritime College, University of Tasmania, Australia ‘Branch’s Elements of Shipping provides the reader with the best all-round examination of the many elements of the international shipping industry. This edition serves as a fitting tribute to Alan Branch and is an essential text for anyone with an interest in global shipping.’ David Adkins, Lecturer in International Procurement and Supply Chain Management, Plymouth Graduate School of Management, Plymouth University ‘Combining the traditional with the modern is as much a challenge as illuminating operations without getting lost in the fascination of the technical detail. This is particularly true for the world of shipping! Branch’s Elements of Shipping is an ongoing example for mastering these challenges. With its clear maritime focus it provides a very comprehensive knowledge base for relevant terms and details and it is a useful source of expertise for students and practitioners in the field.’ Günter Prockl, Associate Professor, Copenhagen Business School, Denmark This page intentionally left blank Branch’s Elements of Shipping Since it was first published in 1964, Elements of Shipping has become established as a market leader. -

Ztráta Soběstačnosti ČR V Oblasti Černého Uhlí: Ohrožení Energetické Bezpečnosti? Bc. Ivo Vojáček

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA FAKULTA SOCIÁLNÍCH STUDIÍ Katedra mezinárodních vztahů a evropských studií Obor Mezinárodní vztahy a energetická bezpečnost Ztráta soběstačnosti ČR v oblasti černého uhlí: ohrožení energetické bezpečnosti? Diplomová práce Bc. Ivo Vojáček Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Tomáš Vlček, Ph.D. UČO: 363783 Obor: MVEB Imatrikulační ročník: 2014 Petrovice u Karviné 2016 Prohlášení o autorství práce Čestně prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci na téma Ztráta soběstačnosti ČR v oblasti černého uhlí: ohrožení energetické bezpečnosti? vypracoval samostatně a výhradně s využitím zdrojů uvedených v seznamu použité literatury. V Petrovicích u Karviné, dne 22. 5. 2016 ……………………. Bc. Ivo Vojáček 2 Poděkování Na tomto místě bych rád poděkoval svému vedoucímu PhDr. Tomáši Vlčkovi, Ph.D. za ochotu, se kterou mi po celou dobu příprav práce poskytoval cenné rady a konstruktivní kritiku. Dále chci poděkovat své rodině za podporu, a zejména svým rodičům za nadlidskou trpělivost, jež se mnou měli po celou dobu studia. V neposlední řadě patří můj dík i všem mým přátelům, kteří mé studium obohatili o řadu nezapomenutelných zážitků, škoda jen, že si jich nepamatuju víc. 3 Láska zahřeje, ale uhlí je uhlí. (Autor neznámý) 4 Obsah 1 Úvod .................................................................................................................................... 7 2 Vědecká východiska práce ................................................................................................ 10 2.2 Metodologie ..............................................................................................................