Determirjiation of the Compensated Gross Tonnage Factors for Superyachts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969

No. 21264 MULTILATERAL International Convention on tonnage measurement of ships, 1969 (with annexes, official translations of the Convention in the Russian and Spanish languages and Final Act of the Conference). Concluded at London on 23 June 1969 Authentic texts: English and French. Authentic texts of the Final Act: English, French, Russian and Spanish. Registered by the International Maritime Organization on 28 September 1982. MULTILAT RAL Convention internationale de 1969 sur le jaugeage des navires (avec annexes, traductions officielles de la Convention en russe et en espagnol et Acte final de la Conf rence). Conclue Londres le 23 juin 1969 Textes authentiques : anglais et fran ais. Textes authentiques de l©Acte final: anglais, fran ais, russe et espagnol. Enregistr e par l©Organisation maritime internationale le 28 septembre 1982. Vol. 1291, 1-21264 4_____ United Nations — Treaty Series Nations Unies — Recueil des TVait s 1982 INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION © ON TONNAGE MEASURE MENT OF SHIPS, 1969 The Contracting Governments, Desiring to establish uniform principles and rules with respect to the determination of tonnage of ships engaged on international voyages; Considering that this end may best be achieved by the conclusion of a Convention; Have agreed as follows: Article 1. GENERAL OBLIGATION UNDER THE CONVENTION The Contracting Governments undertake to give effect to the provisions of the present Convention and the annexes hereto which shall constitute an integral part of the present Convention. Every reference to the present Convention constitutes at the same time a reference to the annexes. Article 2. DEFINITIONS For the purpose of the present Convention, unless expressly provided otherwise: (1) "Regulations" means the Regulations annexed to the present Convention; (2) "Administration" means the Government of the State whose flag the ship is flying; (3) "International voyage" means a sea voyage from a country to which the present Convention applies to a port outside such country, or conversely. -

International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969

Page 1 of 47 Lloyd’s Register Rulefinder 2005 – Version 9.4 Tonnage - International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969 Tonnage - International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969 Copyright 2005 Lloyd's Register or International Maritime Organization. All rights reserved. Lloyd's Register, its affiliates and subsidiaries and their respective officers, employees or agents are, individually and collectively, referred to in this clause as the 'Lloyd's Register Group'. The Lloyd's Register Group assumes no responsibility and shall not be liable to any person for any loss, damage or expense caused by reliance on the information or advice in this document or howsoever provided, unless that person has signed a contract with the relevant Lloyd's Register Group entity for the provision of this information or advice and in that case any responsibility or liability is exclusively on the terms and conditions set out in that contract. file://C:\Documents and Settings\M.Ventura\Local Settings\Temp\~hh4CFD.htm 2009-09-22 Page 2 of 47 Lloyd’s Register Rulefinder 2005 – Version 9.4 Tonnage - International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969 - Articles of the International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships Articles of the International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships Copyright 2005 Lloyd's Register or International Maritime Organization. All rights reserved. Lloyd's Register, its affiliates and subsidiaries and their respective officers, employees or agents are, individually and collectively, referred to in this clause as the 'Lloyd's Register Group'. The Lloyd's Register Group assumes no responsibility and shall not be liable to any person for any loss, damage or expense caused by reliance on the information or advice in this document or howsoever provided, unless that person has signed a contract with the relevant Lloyd's Register Group entity for the provision of this information or advice and in that case any responsibility or liability is exclusively on the terms and conditions set out in that contract. -

Shipbuilding

Shipbuilding A promising rst half, an uncertain second one 2018 started briskly in the wake of 2017. In the rst half of the year, newbuilding orders were placed at a rate of about 10m dwt per month. However the pace dropped in the second half, as owners grappled with a rise in newbuilding prices and growing uncertainty over the IMO 2020 deadline. Regardless, newbuilding orders rose to 95.5m dwt in 2018 versus 83.1m dwt in 2017. Demand for bulkers, container carriers and specialised ships increased, while for tankers it receded, re ecting low freight rates and poor sentiment. Thanks to this additional demand, shipbuilders succeeded in raising newbuilding prices by about 10%. This enabled them to pass on some of the additional building costs resulting from higher steel prices, new regulations and increased pressure from marine suppliers, who have also been struggling since 2008. VIIKKI LNG-fuelled forest product carrier, 25,600 dwt (B.Delta 25), built in 2018 by China’s Jinling for Finland’s ESL Shipping. 5 Orders Million dwt 300 250 200 150 100 50 SHIPBUILDING SHIPBUILDING KEY POINTS OF 2018 KEY POINTS OF 2018 0 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Deliveries vs demolitions Fleet evolution Deliveries Demolitions Fleet KEY POINTS OF 2018 Summary 2017 2018 Million dwt Million dwt Million dwt Million dwt Ships 1,000 1,245 Orders 200 2,000 m dwt 83.1 95.5 180 The three Asian shipbuilding giants, representing almost 95% of the global 1,800 orderbook by deadweight, continued to ght ercely for market share. -

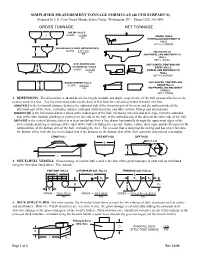

SIMPLIFIED MEASUREMENT TONNAGE FORMULAS (46 CFR SUBPART E) Prepared by U.S

SIMPLIFIED MEASUREMENT TONNAGE FORMULAS (46 CFR SUBPART E) Prepared by U.S. Coast Guard Marine Safety Center, Washington, DC Phone (202) 366-6441 GROSS TONNAGE NET TONNAGE SAILING HULLS D GROSS = 0.5 LBD SAILING HULLS 100 (PROPELLING MACHINERY IN HULL) NET = 0.9 GROSS SAILING HULLS (KEEL INCLUDED IN D) D GROSS = 0.375 LBD SAILING HULLS 100 (NO PROPELLING MACHINERY IN HULL) NET = GROSS SHIP-SHAPED AND SHIP-SHAPED, PONTOON AND CYLINDRICAL HULLS D D BARGE HULLS GROSS = 0.67 LBD (PROPELLING MACHINERY IN 100 HULL) NET = 0.8 GROSS BARGE-SHAPED HULLS SHIP-SHAPED, PONTOON AND D GROSS = 0.84 LBD BARGE HULLS 100 (NO PROPELLING MACHINERY IN HULL) NET = GROSS 1. DIMENSIONS. The dimensions, L, B and D, are the length, breadth and depth, respectively, of the hull measured in feet to the nearest tenth of a foot. See the conversion table on the back of this form for converting inches to tenths of a foot. LENGTH (L) is the horizontal distance between the outboard side of the foremost part of the stem and the outboard side of the aftermost part of the stern, excluding rudders, outboard motor brackets, and other similar fittings and attachments. BREADTH (B) is the horizontal distance taken at the widest part of the hull, excluding rub rails and deck caps, from the outboard side of the skin (outside planking or plating) on one side of the hull, to the outboard side of the skin on the other side of the hull. DEPTH (D) is the vertical distance taken at or near amidships from a line drawn horizontally through the uppermost edges of the skin (outside planking or plating) at the sides of the hull (excluding the cap rail, trunks, cabins, deck caps, and deckhouses) to the outboard face of the bottom skin of the hull, excluding the keel. -

Measurement of Fishing

35 Rapp. P.-v. Réun. Cons. int. Explor. Mer, 168: 35-38. Janvier 1975. TONNAGE CERTIFICATE DATA AS FISHING POWER PARAMETERS F. d e B e e r Netherlands Institute for Fishery Investigations, IJmuiden, Netherlands INTRODUCTION London, June 1969 — An entirely new system of The international exchange of information about measuring the gross and net fishing vessels and the increasing scientific approach tonnage was set up called the to fisheries in general requires the use of a number of “International Convention on parameters of which there is a great variety especially Tonnage Measurement of in the field of main dimensions, coefficients, propulsion Ships, 1969” .1 data (horse power, propeller, etc.) and other partic ulars of fishing vessels. This variety is very often caused Every ship which has been measured and marked by different historical developments in different in accordance with the Convention concluded in Oslo, countries. 1947, is issued with a tonnage certificate called the The tonnage certificate is often used as an easy and “International Tonnage Certificate”. The tonnage of official source for parameters. However, though this a vessel consists of its gross tonnage and net tonnage. certificate is an official one and is based on Inter In this paper only the gross tonnage is discussed national Conventions its value for scientific purposes because net tonnage is not often used as a parameter. is questionable. The gross tonnage of a vessel, expressed in cubic meters and register tons (of 2-83 m3), is defined as the sum of all the enclosed spaces. INTERNATIONAL REGULATIONS ON TONNAGE These are: MEASUREMENT space below tonnage deck trunks International procedures for measuring the tonnage tweendeck space round houses of ships were laid down as follows : enclosed forecastle excess of hatchways bridge spaces spaces above the upper- Geneva, June 1939 - International regulations for break(s) deck included as part of tonnage measurement of ships poop the propelling machinery were issued through the League space. -

Branch's Elements of Shipping/Alan E

‘I would strongly recommend this book to anyone who is interested in shipping or taking a course where shipping is an important element, for example, chartering and broking, maritime transport, exporting and importing, ship management, and international trade. Using an approach of simple analysis and pragmatism, the book provides clear explanations of the basic elements of ship operations and commercial, legal, economic, technical, managerial, logistical, and financial aspects of shipping.’ Dr Jiangang Fei, National Centre for Ports & Shipping, Australian Maritime College, University of Tasmania, Australia ‘Branch’s Elements of Shipping provides the reader with the best all-round examination of the many elements of the international shipping industry. This edition serves as a fitting tribute to Alan Branch and is an essential text for anyone with an interest in global shipping.’ David Adkins, Lecturer in International Procurement and Supply Chain Management, Plymouth Graduate School of Management, Plymouth University ‘Combining the traditional with the modern is as much a challenge as illuminating operations without getting lost in the fascination of the technical detail. This is particularly true for the world of shipping! Branch’s Elements of Shipping is an ongoing example for mastering these challenges. With its clear maritime focus it provides a very comprehensive knowledge base for relevant terms and details and it is a useful source of expertise for students and practitioners in the field.’ Günter Prockl, Associate Professor, Copenhagen Business School, Denmark This page intentionally left blank Branch’s Elements of Shipping Since it was first published in 1964, Elements of Shipping has become established as a market leader. -

Development of a Methodology for Estimation of Ballast Water Imported to Australian Ports

J. Basic. Appl. Sci. Res. , 6(5 )14-25 , 2016 ISSN 2090-4304 Journal of Basic and Applied © 2016, TextRoad Publication Scientific Research www.textroad.com Development of a Methodology for Estimation of Ballast Water Imported to Australian Ports Joel Lim Xiao Yoong, Hossein Enshaei Australian Maritime College, University of Tasmania Received: February 16, 2016 Accepted: April 21, 2016 ABSTRACT The importance of identifying the location and magnitude of risks imposed from ship-mediated bioinvasion in Australia is significant after the assessment of previous events that have impacted the Australian ecosystem and economy. This paper provides an overview of the developed methodology adopted for the estimation of ballast water imported to Australian ports. The resultant amount of ballast water discharged for a total of 31ports in a period of five years was estimated and results were presented. A high level of risk was identified at the north- west of Australia, where 60 percent of the total ballast water imported was discharged for the year 2013. A significantly large amount of ballast water was also discovered in the regions of Newcastle and Hay Point. It was discovered that bulk carriers account for 94 percent of mediated ballast water. Proportion factors for predictions have been established based on the relation between the mass of freight exported with the amount of ballast water discharged. The study recommends a sensitivity analysis of proportion factors based on varying selected deadweight for individual ship type and size categories. To mitigate risks from ship-mediated bioinvasion, the origin of the ballast water imported should be investigated as well as the type of foreign marine life introduced. -

JAPAN SHIP EXPORTERS' ASSOCIATION IHI MU Delivers

No. 303 Feb. - Mar. 2004 IHI MU delivers large container carrier to NYK IHI Marine United Inc. (IHI MU) has delivered the NYK Depth, mld,: 23.90m Argus, a large container carrier with a container carrying Draught, mld.: 14.035m capacity of 6,492TEU, to Glorious River Line S.A. at the Gross tonnage: 75,484t Kure Shipyard. This ship is the sixth of seven container Deadweight tonnage: 81,171t carriers completed for NYK. The NYK Argus is the Main engine: DU-Sulzer 12RTA96C diesel x 1 unit OverPanamax type put in service between Europe and MCR: 61,350kW x 97.7rpm the Far East. Complement: 30 Principal particulars Speed, service: approx. 25.0kt Length (o.a.): 284.00m Classification: NK Breadth, mld.: 40.00m Completion: Feb. 4, 2004 For further information please contact: Website: http://www.jsea.or.jp JAPAN SHIP EXPORTERS' ASSOCIATION 15-16, Toranomon 1-chome, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-0001 Tel: (03) 3508-9661 Fax: (03) 3508-2058 E-Mail: [email protected] Topics No. 303 Feb. - Mar. Page 2 28,171t IHI MU delivers Future 48 to Nomikos Main engine: DU-Sulzer 6RTA48T IHI Marine United Inc. (IHI MU) standard type bulk carrier in the fam- diesel x 1 unit has completed ASTRA, a 48,000DWT ily tree of Freedom, Fortune, Friend- Service speed: 14.5kt bulk carrier, Future 48 (F-48), for AM ship, Freedom Mk-II, Future-32 and Complement: 25 Nomikos Transworld Maritime at the 32A, and Future-42 types. Classification: NK Yokohama Shipyard. The vessel is the Principal par- first of the series of three vessels or- ticulars (stan- dered by the same Greek owner. -

Assessment of Shipping's Efficiency Using Satellite AIS Data

UCL ENERGY INSTITUTE Assessment of Shipping’s Efficiency Using Satellite AIS data Tristan Smith, Eoin O’Keeffe, Lucy Aldous and Paolo Agnolucci Prepared for the International Council on Clean Transportation March 2013 CONTENTS CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................................................. i LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................................................................................... v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................................................... vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................................... 1 OBJECTIVE ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 METHOD .............................................................................................................................................................. 1 FURTHER WORK .................................................................................................................................................. 2 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................... -

The Misuse of RMS Titanic As a Benchmark for Ship Size

The misuse of RMS Titanic as a benchmark for ship size Paul Stott 6th February 2014 Benchmarks in popular reporting of Science ≡ 11 elephants Popular reporting often makes use of tangible common objects to convey size This is relatively easy with linear or square dimensions and weight Benchmarks in popular reporting of Science For ships the default is often to compare the ship to RMS Titanic to try to convey a sense of a vessel’s size: BBC Radio 4, Today Programme, 16th Sept 2013: “Costa Concordia weighs twice as much as the Titanic” BBC Newsround, 16th Septeber 2013: “Costa Concordia weighs twice as much as the Titanic” ExtremeTech.com: “Costa Concordia: How a ship twice the size of Titanic is being lifted from the seabed” Use of RMS Titanic as a benchmark The intent of this comparison is laudable: it is to convey the heroic nature of the salvors in man-handling something that is very large. So, where is the problem? ≡ 2x Use of RMS Titanic as a benchmark Problem number 1: The common misinterpretation of the meaning of Gross Tonnage as a measure of weight. BBC Radio 4, Today Programme, 16th Sept 2013: “Costa Concordia weighs twice as much as the Titanic” BBC Newsround, 16th Septeber 2013: “Costa Concordia weighs twice as much as the Titanic” 114,147 Gross Tons 46,320 Gross Tons Use of RMS Titanic as a benchmark Problem number 1: The common misinterpretation of the meaning of Gross Tonnage as a measure of weight. In terms of tonnage, Costa Concordia is 2.5 times the size of Titanic, so the BBC’s statement appears approximately correct…. -

Review of Maritime Transport 2011

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT REVIEW OF MARITIME TRANSPORT 2011 Report by the UNCTAD secretariat Chapter 2 UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2011 2 STRUCTURE, OWNERSHIP AND REGISTRATION OF THE WORLD FLEET CHAPTER 2 The year 2010 saw record deliveries of new tonnage, 28 per cent higher than in 2009, resulting in an 8.6 per cent growth in the world eet. The world merchant eet reached almost 1.4 billion deadweight tons in January 2011, an increase of 120 million dwt over 2010. New deliveries stood at 150 million dwt, against demolitions and other withdrawals from the market of approximately 30 million dwt. Since 2005, the dry bulk eet has almost doubled, and the containership eet has nearly tripled. The share of foreign- agged tonnage reached an estimated 68 per cent in January 2011. This chapter presents the supply-side dynamics of the world maritime industry. It covers the structure, age prole, ownership and registration of the world eet. The chapter also reviews deliveries, demolitions, and tonnage on order. 36 Review of MaRitiMe tRanspoRt 2011 A. structure of the world fleet The share of dry bulk tonnage has gone up from 27 per cent to 38 per cent since 1980, while the share of 1. world fleet growth and principal oil tankers has decreased from almost 50 per cent to vessel types 34 per cent. The world fleet in 2011 Long-term trends in vessel types In January 2011, there were 103,392 seagoing The composition of the world fleet reflects the demands commercial ships in service, with a combined tonnage for seaborne trade of different commodities, including of 1,396 million dwt. -

A Measurement of Shipbuilding Productivity

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 16 September 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202009.0351.v1 A Measurement of Shipbuilding Productivity P.Z. Roque & J.M. Gordo CENTEC, Instituto Superior Técnico, Lisbon, Portugal ABSTRACT: The present work studies the concept of productivity in shipbuilding and how it should be measured. The existing metrics, shipbuilding process and shipyard organization were studies in order to choose the most ade- quate metrics which would allow the measuring of a shipyard productivity in a systematic and holistic way. This is achieved by gathering the man-hours spent in each ship organized by cost centre and using Compensated Gross Ton- nages as the measure of output from the shipyard. Data was gathered for thirty ships built in the same European yard organized by cost centre. From the data collected it was found that the ratio of hours spent in outfitting to the hours spent in structures is proportional to the complexity of the ship. There was also opportunity to study the work reduc- tion resulting from building ships in series and the shares of labour for ships series and across ship types. Keywords: Shipbuilding; productivity; block's manufacturing; manufacturing cost 1 INTRODUCTION terms in the shipbuilding industry and finding different In the current times shipbuilding faces several challenges, methods to quantify them. on one hand shipyards must compete in a fierce interna- Independently of the various forms of quantifying a tional market while on the other hand shipyards, which shipyard’s efficiency, it is necessary to have a holistic are usually traditional and conservative, must adapt to a understanding of not only the assets but of all the steps quickly changing market and technologies.