4.7. Wetlands, Riparian, and Littoral Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 30 Final DOT Layout.Indd

Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities 2010 Department Overview June 30, 2011 THE MISSION of the Department of Transportation and Public Facilities is to provide for the safe and effi cient movement of people and goods and the delivery of state services. Table of Contents Letter from Commissioner Luiken . 3 Introduction . 4 Challenges in Alaska Transportation . .5-7 Long Range Transportation Policy Plan . 8 Statewide Transportation Improvement Plan (STIP) . 9-11 Budget . 12 Divisions and Responsibilities . 13 Statewide Aviation . 13 International Airports . 14 Marine Highway System . 15 Surface Transportation . 16 Transportation Operations . 17-18 Bridge Section . 19 Ports and Harbors . 20 Resource Roads. 21 Transportation Safety . 22 Statewide Systems . 23 Bicycle and Pedestrian Program . 24 Data Services . 25 Buildings and Facilities . 26 Measurement Standards . 27 The Road Ahead . 28 The 2010 Department Overview was produced by the Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities in Juneau, Alaska, at a cost of $9.96 per copy. Cover and inside cover photos (Kodiak roads), back cover (M/V Columbia, Auke Bay), and this page (Dutch Harbor bridge), by Peter Metcalfe 2 Waterfront construction, Kotzebue, by Peter Metcalfe June 30, 2011 Dear Fellow Alaskan, As the Commissioner of the Department of Transportation and Public Facilities, it is my pleasure to present the 2010 Department Overview. All Alaskans use the state’s transportation system, whether they are driving to work, headed for the outdoors, meeting the ferry, or catching a fl ight at the local airport. We use these transportation systems daily, and often take them for granted, unaware of the effort that happens behind the scenes to keep the systems working. -

DOTPF Alaskan Airports, AIP, APEB

Northern Region Airport Overview -------------------------------------------- DOT&PF Town Hall Meeting October 22, 2010 Jeff Roach, Aviation Planner Northern Region, DOT&PF Topics • Northern Region Airports • Northern Region Aviation Sections • Aviation Funding • Types of Projects • Anticipated Future Funding Levels • Anticipated Northern Region Projects Northern Region 105 Airports 40% of the State’s airports are in the Northern Region • One International Airport • Seaplane Bases • Community Airports • Public, Locally Owned Airports Northern Region Aviation Organization • Planning • Design • Construction • Airport Leasing • Maintenance and Operations (M&O) Aviation Planning • Identify project needs, develops project packages for APEB scoring • Develop project scopes • Conduct airport master plans Project Needs Identification Rural Airports Needs List Development Project needs collected from: • Public, aviation interests, community representatives, DOT&PF and FAA staff, Legislature • DOT&PF Staff (Design, M&O, Leasing) • Needs identified in airport master plans • Regional transportation plans Project Scoping: DOT&PF Regional staff evaluate potential projects to develop preliminary project scope, cost estimate and other supporting information for APEB project evaluation State AIP Project Scoring (APEB) Aviation Project Evaluation Board (APEB): • The APEB is a six-member airport capital project review and evaluation group composed of DOT&PF’s Deputy Commissioner, three Regional Directors (SE, CR, NR), Statewide Planning Director, and State -

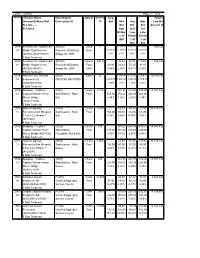

Remote Desktop Redirected Printer

%208% %208% Page 1 of 6 Opened --Project Name Item Number Unit (f) Quantity Eng Project (VersionID/Aksas/Ref. Description (f) (f) Est Min Avg Max Low Bid Std. ID)------ Bid Bid Bid Amount (f) 66 Listed Low 2nd 3rd Bidder Low Low % of Bidder Bidder Bid % of % of Bid Bid 2018 Nenana Little Goldstream 202(23) Lump 1 21,500.00 48,055.56 76,000.00 936,532 01 Bridge Replacement Removal of Existing Sum 65,000.00 21,500.00 52,000.00 30,000.00 (#2080) (45491//5517) Bridge No. 2080 3.98% 2.30% 5.51% 3.00% 9 Bids Tendered 2018 Nenana Little Goldstream 202(23) Square 942.0 22.82 51.01 80.68 936,532 01 Bridge Replacement Removal of Existing Foot 69.00 22.82 55.20 31.85 (#2080) (45491) Bridge No. 2080 (Alt) 3.98% 2.30% 5.51% 3.00% 9 Bids Tendered 2014 Haines Ferry Terminal 208(1) Each 21 1,000.00 6,612.50 9,950.00 14,979,745 05 Improvements GROUND ANCHORS 5,000.00 8,500.00 9,950.00 7,000.00 (39251/68433/0) 1.08% 1.19% 1.30% 0.91% 4 Bids Tendered 2016 Skagway - Replace 208(1) Linear 2,100 158.22 249.64 390.00 18,907,426 12 Captain William Henry Stabilization - Rock Foot 355.00 158.22 200.00 200.00 Moore Bridge Bolt 5.44% 1.76% 2.08% 1.94% (46281//1432) 5 Bids Tendered 2017 Haines Highway 208(1) Linear 3,885 55.00 66.50 80.00 36,149,513 11 Reconstruction Milepost Stabilization - Rock Foot 160.00 80.00 76.00 55.00 3.9 to 12.2, Phase 1 Bolt 1.68% 0.86% 0.80% 0.53% (47539//0) 4 Bids Tendered 2016 Skagway - Replace 208(2) Linear 875 158.22 248.44 359.00 18,907,426 12 Captain William Henry Stabilization - Foot 415.00 158.22 225.00 200.00 Moore Bridge (46281//0) -

FEDERAL REGISTER INDEX January–October 2019

FEDERAL REGISTER INDEX January–October 2019 Transportation Department GA 8 Airvan (Pty) Ltd Airplanes – 16202 ( Apr 18) RULES GE Honda Aero Engines Turbofan Engines – 39176 ( Aug 9) General Electric Company Turbofan Engines – 2709 ( Feb 8) Airspace Designations – 45651 ( Aug 30) Gulfstream Aerospace LP (Type Certificate Previously Held by Israel Airspace Designations: Aircraft Industries, Ltd.) Airplanes – 7272 ( Mar 4) Incorporation by Reference Amendments – 52757 ( Oct 3) Honeywell International Inc. Turbofan Engines – 10403 ( Mar 21) Airworthiness Criteria: HPH s. r.o. Gliders – 12880 ( Apr 3) Glider Design Criteria for Alexander Schleicher GmbH & Co. International Aero Engines AG Turbofan Engines – 11642 ( Mar 28); 41621 Segelflugzeugbau Model ASK 21 B Glider – 27707 ( Jun 14) ( Aug 15); 47406 ( Sep 10) Special Class Airworthiness Criteria for the Yamaha Fazer R – 17942 International Aero Engines Turbofan Engines – 2715 ( Feb 8); 11214 ( Apr 29) ( Mar 26); 13105 ( Apr 4); 27511 ( Jun 13) Airworthiness Directives: Learjet, Inc. Airplanes – 45068 ( Aug 28) 328 Support Services GmbH (Type Certificate previously held by AvCraft Leonardo S.p.A. (Type Certificate Previously Held by Finmeccanica S.p.A., Aerospace GmbH; Fairchild Dornier GmbH; Dornier Luftfahrt GmbH) AgustaWestland S.p.A) Helicopters – 24703 ( May 29) Airplanes – 41599 ( Aug 15) Leonardo S.p.A. Helicopters – 8965 ( Mar 13); 29797 ( Jun 25); 30866 Airbus Helicopters – 8250 ( Mar 7); 22693 ( May 20); 47877 ( Sep 11); 56109 ( Jun 28); 47875 ( Sep 11) ( Oct 21) Lockheed Martin -

FEDERAL REGISTER INDEX January–October 2019

FEDERAL REGISTER INDEX January–October 2019 Federal Aviation Administration GA 8 Airvan (Pty) Ltd Airplanes – 16202 ( Apr 18) RULES GE Honda Aero Engines Turbofan Engines – 39176 ( Aug 9) General Electric Company Turbofan Engines – 2709 ( Feb 8) Airspace Designations – 45651 ( Aug 30) Gulfstream Aerospace LP (Type Certificate Previously Held by Israel Airspace Designations: Aircraft Industries, Ltd.) Airplanes – 7272 ( Mar 4) Incorporation by Reference Amendments – 52757 ( Oct 3) Honeywell International Inc. Turbofan Engines – 10403 ( Mar 21) Airworthiness Criteria: HPH s. r.o. Gliders – 12880 ( Apr 3) Glider Design Criteria for Alexander Schleicher GmbH & Co. International Aero Engines AG Turbofan Engines – 11642 ( Mar 28); 41621 Segelflugzeugbau Model ASK 21 B Glider – 27707 ( Jun 14) ( Aug 15); 47406 ( Sep 10) Special Class Airworthiness Criteria for the Yamaha Fazer R – 17942 International Aero Engines Turbofan Engines – 2715 ( Feb 8); 11214 ( Apr 29) ( Mar 26); 13105 ( Apr 4) Airworthiness Directives: Learjet, Inc. Airplanes – 45068 ( Aug 28) 328 Support Services GmbH (Type Certificate previously held by AvCraft Leonardo S.p.A. (Type Certificate Previously Held by Finmeccanica S.p.A., Aerospace GmbH; Fairchild Dornier GmbH; Dornier Luftfahrt GmbH) AgustaWestland S.p.A) Helicopters – 24703 ( May 29) Airplanes – 41599 ( Aug 15) Leonardo S.p.A. Helicopters – 8965 ( Mar 13); 29797 ( Jun 25); 30866 Airbus Helicopters – 8250 ( Mar 7); 22693 ( May 20); 47877 ( Sep 11); 56109 ( Jun 28); 47875 ( Sep 11) ( Oct 21) Lockheed Martin Corporation/Lockheed -

AASP Mission, Goals, Measures, & Classifications

Mission, Goals, Measures and Classifications A COMPONENT OF THE November 2011 Prepared for With a Grant from Alaska Department Federal Aviation of Transportation and Administration Public Facilities Prepared by: As subconsultants to: WHPACIFIC, Inc. DOWL HKM 300 W. 31st Avenue 4041 B Street Anchorage, Alaska 99503 www.AlaskaASP.com Anchorage, Alaska 99503 907-339-6500 907-562-2000 A message from the Desk of Steven D. Hatter, Deputy Commissioner – Aviation I am pleased to present this report on the Mission, Goals, Performance Measures and Classifications of Alaska’s Airports. The goals, objectives, performance measures, and airport classifications presented herein establish a framework to set priorities and guide our work in aviation. They also provide mechanisms to help implement the aviation-related goals and priorities identified in the Alaska Statewide Transportation Policy Plan (“Let’s Get Moving 2030”) and the Department’s 2011 Strategic Agenda. The development of a relevant and integrated system of goals, objectives, and performance measures provides the Department with a powerful tool for communicating with the public and legislators, managing resources, and motivating employees. Our goals are general guidelines that explain what is to be achieved by the Department’s aviation programs. Our objectives define the specific strategies or implementation steps we will take to attain the goals – the “who, what, when, where, and how” of reaching the goals. Our performance measures provide statistical evidence to indicate whether progress is being made towards our objectives. Performance measures are an essential tool in public administration, used to direct resources and ensure that programs are producing intended results. Alaska has over 700 registered airports and these airports vary widely in size, use, and the amount of infrastructure and facility development. -

06-'12, Rural Airports AIP Spending Plan October 20, 2010 DOT/PF, Statewide Aviation

Draft FFY '06-'12, Rural Airports AIP Spending Plan October 20, 2010 DOT/PF, Statewide Aviation APEB LOCID Project Score Ph FFY'06 FFY'07 FFY'08 FFY'09 FFY'10 FFY'11 FFY'12 After FFY'12 Rural Primary Airports Primary Airfield Projects ANI Aniak Airport Improvements 130 2,3,4 $ 4,700,000 BRW Barrow Apron Expansion 88 2,4 $ 7,000,000 BRW Barrow RWY-Apron Paving/ SA Expan-Stg 3 124 2,4$ 3,000,000 BRW Barrow RWY-Apron Paving/ SA Expan-Stg 4 124 2,4 $ 7,200,000 Bethel Parallel RWY and Other Improv--Stg 2 BET (GA Apron Expansion) 130 2,4$ 5,701,583 Bethel Parallel RWY and Other Improv--Stg 3 (Parallel Runway Gravel Surface and BET Lighting) 160 2,4$ 2,733,217 Bethel Parallel RWY and Other Improv--Stg 4 (Parallel Runway Gravel Surface and BET Lighting) 160 2,4$ 5,877,983 Bethel Parallel RWY and Other Improv--Stg 5 BET (Parallel Runway Paving) 160 2,4$ 3,277,634 Bethel Parallel RWY and Other Improv--Stg 6 BET (ROW) 130 2,4 $ 1,650,000 BET Bethel West Heavy Apron Expansion 101 2,4 $ 4,000,000 Bethel Airport RWY / TWY / Commerical BET Apron Pavement Rehabilitation (C) N/A 2,4 $ 13,000,000 Bethel Airport RWY / TWY / Commerical BET Apron Pavement Rehabilitation N/A 2,4 $ 13,000,000 BET Bethel South GA Apron Reconstruction (C) N/A 2,4 $ 4,700,000 BET Bethel South GAApron Reconstruction N/A 2,4 $ 4,700,000 CDV Cordova Apt Apron, TWY & GA Imp Stg 1 113 2,4$ 4,499,980 CDV Cordova Apt Apron, TWY & GA Imp Stg 2 113 2,4 $ 8,500,000 CDV Cordova Apt Apron, TWY & GA Imp Stg 2 (C) 113 2,4 $ 8,500,000 CDV Cordova Apt Apron, TWY & GA Imp Stg 3 113 2,4 $ 6,700,000 CDV Cordova Apt RSA Expan - Stg 2 N/A 2,4$ 4,346,424 CDV Cordova Apt RSA Improvements (Paving) 65 2,4$ 650,000 Note: Spending Plan contains entitlement and discretionary funded projects. -

Project Election Project Title Cost Project Description Location District (1,000'S) Klawock Airport Hardstands 130.0 Install

FY2013 Aviation - Deferred Maintenance Inventory/Backlog Project Election Project Title Cost Project Description Location District (1,000's) Klawock Airport Install new hardstands for increased jet traffic in Klawock 130.0 2 Hardstands order to minimize pavement damage Kake Kake Airport Security 50.0 Repair over 100 holes in security fence 5 Fence Hole Repairs Gustavus Airport Gustavus Supplemental Lighted 35.0 Install new supplemental Lighted Wind cone 5 Wind Cone Haines Lease Lot Haines 25.0 Place and compact D-1 on lease lot access taxiway 5 Access Improvement Gustavus Vegetation Cut vegetation on Runway Safety Areas 11/29 and Gustavus 20.0 5 Control 2/20 At Cordova Airport identify and remove trees that Valdez Tree Removal Cordova 50.0 5 penetrate runway 16-34 glide slope District Total HD 5 180.0 Stoney River Airport 400.0 Runway rehabilitation Stoney River 6 Interior Airport Cut Vegetation at five interior airports – Rampart, 75.0 Interior 6 Vegetation Control Stevens Village, Beaver, Hughes, Huslia Total HD 6 475.0 Healy River Airport lighting is in need of updating Healy River Airport 300.0 using conduit and cans instead of direct burial and Denali District 8 Lighting lights which are stuck in traffic cones Tazlina Lake Louise Airport 60.0 Apply dust palliative to Lake Louise Airport. District/ 12 Dust Palliative Nelchina Kake Vegetation Kake 75.0 Cut Vegetation on Runway Safety Area 11/29 35 Control Klawock Vegetation Klawock 35.0 Cut vegetation on Runway Safety Area 2/20 35 Control Total HD 35 110.0 Old Harbor Airport 150.0 Surface course Old Harbor 36 Larson Bay Airport 25.0 Lighting system repairs, windsock pole replacement Larson Bay 36 Total HD 36 175.0 King Salmon Airport 75.0 Fence and gate repair King Salmon 37 Chignik Chignik Lagoon Airport 25.0 Windsock, poles and markers 37 Lagoon Total HD 37 100.0 Red Devil Airport 150.0 Gravel surfacing Red Devil 38 Replace approx. -

2007-2009 Construction Project Summary

NORTHERN REGION DOT & PF CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS 2008 - 2009 SUMMARY Highway Aviation Facility Est Value Est Value Est Value Community # of Pjs Thousands # of Pjs Thousands # of Pjs Thousands Alakanuk 1 $5,000.0 Alaska Highway 2 $55,400.0 1 $3,000.0 Anvik 1 $8,000.0 Barrow 2 $6,000.0 1 $25,500.0 Chitina 1 $1,100.0 Circle 1 $900.0 Copper River Highway 1 $2,500.0 Cordova 1 $3,500.0 1 $2,000.0 Dalton Highway 5 $50,100.0 Deadhorse 1 $500.0 Eagle 1 $1,300.0 Emmonak 3 $5,700.0 Fairbanks 2 $11,421.0 2 $46,800.0 1 $99,000.0 FMATS 15 $66,930.0 Fort Yukon 1 $1,600.0 Galena 1 $1,200.0 Gambell 1 $4,800.0 Grayling 1 $9,300.0 Hughes 1 $988.0 Huslia 1 $650.0 Kivalina 1 $1,000.0 Kotzebue 2 $23,000.0 1 $400.0 1 $2,400.0 Lake Louise 1 $1,700.0 Manley 1 $200.0 1 $12,000.0 Marshall 1 $1,100.0 Minto 1 $7,000.0 Nome 7 $10,472.0 2 $6,800.0 1 $9,800.0 Northway 1 $15,300.0 Parks Highway 4 $26,400.0 Point Hope 2 $5,000.0 Richardson Highway 1 $21,800.0 1 $11,000.0 Savoogna 1 $10,000.0 Selawik 2 $5,200.0 Shaktoolik 1 $800.0 Shishmaref 1 $2,000.0 1 $200.0 Steese Hwy 2 $9,600.0 Stevens Village 1 $2,000.0 Tanana 1 $8,900.0 Unalakleet 2 $3,700.0 1 $21,100.0 Valdez 1 $2,700.0 Total Communities Total Projects 65 $324,261.0 21 $183,300.0 6 $127,200.0 GRAND TOTAL 92 $634,761.0 ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION AND PUBLIC FACILITIES NORTHERN REGION CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS CURRENT AND EXPECTED 2008 - 2009 ALAKANUK ALAKANUK AIRPORT RELOCATION Contractor: Knik Construction Co., Inc. -

Remote Desktop Redirected Printer

%650% %650% Page 1 of 7 Opened --Project Name Item Number Unit (f) Quantity Eng Project (VersionID/Aksas/Ref. Description (f) (f) Est Min Avg Max Low Bid Std. ID)------ Bid Bid Bid Amount (f) 74 Listed Low 2nd 3rd Bidder Low Low % of Bidder Bidder Bid % of % of Bid Bid 2012 Sgy - Pedestrian 650(1) Each 4 1,000.00 2,334.76 4,100.00 404,660 06 Improvements Aluminum Interpretive 6,000.00 1,904.29 1,000.00 4,100.00 (30593/69304/0) Sign Frame and 5.59% 1.88% 0.95% 3.72% 3 Bids Tendered Footing 2015 Olympic Mountain Loop 650(1) Square 6,100 5.50 8.05 11.00 2,364,890 01 Improvements - Girdwood Grass Pavers Foot 6.00 10.25 6.00 5.95 (44236/59766/0) 1.93% 2.64% 1.36% 1.30% 8 Bids Tendered 2010 King Cove Access Road 650(1) LUMP 1 1,500,000.00 2,361,061.85 2,874,068.00 14,459,880 12 Completion RELOCATE SUM 2,200,000.00 2,874,068.00 1,800,000.00 2,503,674.24 (32716/59791/7843) HOVERCRAFT 14.94% 19.88% 11.69% 15.29% 12 Bids Tendered TERMINAL 2009 Psg Falls Creek Fish 650(1) Each 2.0 12,000.00 12,604.00 13,000.00 141,900 02 Ladder Repairs (18352) Sluice Gate (Alt) 22,000.00 13,000.00 12,812.00 12,000.00 3 Bids Tendered 31.34% 18.32% 18.00% 13.75% 2009 Psg Falls Creek Fish 650(1) Lump 1 24,000.00 25,208.00 26,000.00 141,900 02 Ladder Repairs Sluice Gate Sum 44,000.00 26,000.00 25,624.00 24,000.00 (18352/68399/0) 31.34% 18.32% 18.00% 13.75% 3 Bids Tendered 2014 Annette Bay Ferry 650(1) Lump 1 22,774.05 22,774.05 22,774.05 781,909 11 Terminal Improvements TERO Fee Sum 21,899.40 22,774.05 0.00 0.00 (43416/68135/0) 2.91% 2.91% 0.00% 0.00% 1 Bids Tendered -

Northern Region Construction and CIP Support

Component — Northern Region Construction and CIP Support State of Alaska FY2012 Governor’s Operating Budget Department of Transportation/Public Facilities Northern Region Construction and CIP Support Component Budget Summary FY2012 Governor Released December 15, 2010 12/16/10 9:19 AM Department of Transportation/Public Facilities Page 1 Component — Northern Region Construction and CIP Support Component: Northern Region Construction and CIP Support Contribution to Department's Mission Improve the transportation system in Alaska and protect the health and safety of Alaska's people by constructing safe, environmentally sound, reliable and cost-effective highways, airports, harbors, docks, and buildings. Core Services Construction Branch: Administers construction contracts, provides field inspection and construction oversight, provides quality assurance that construction documentation and materials are in conformance with contract requirements during construction, provides closeout of projects, and provides information to the Civil Rights Office regarding Disadvantaged Business Enterprises/Minority Business Enterprise activity on construction projects. Project Control Branch: Coordinates and programs project funding; administers state and federal grants; provides engineering management support; prepares and manages the component's operating budget; develops, maintains data within the Oracle management reporting system for capital projects; provides regional network administration and desktop computer support; and processes time and equipment charges to projects. Key Component Challenges The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) program has added projects that have additional administrative reporting and tracking requirements. This requires more work in comparison to projects in the normal program. In cooperation with the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) we are continuing to institute expanded safety education, oversight, and traffic control requirements. -

Airports Not Meeting Demand for Lease Lot Space

Evolution of the Alaska Aviation System Plan State of Alaska Classifications and Performance Measures September 2015 Source: CDM Smith, DOWL Figure 34: Airports Not Meeting Demand for Lease Lot Space Page 66 Evolution of the Alaska Aviation System Plan State of Alaska Classifications and Performance Measures September 2015 Source: CDM Smith, DOWL Figure 35: Airports Not Meeting Demand for Tie-Down Space Page 67 Evolution of the Alaska Aviation System Plan State of Alaska Classifications and Performance Measures September 2015 Source: CDM Smith, DOWL Figure 36: Airports Without a Passenger Shelter Page 68 Evolution of the Alaska Aviation System Plan State of Alaska Classifications and Performance Measures September 2015 Source: CDM Smith, DOWL Figure 37: Airports Without Public Toilet Facilities Page 69 Evolution of the Alaska Aviation System Plan State of Alaska Classifications and Performance Measures September 2015 The following sections detail Service Indices at Regional, Community Off-Road, and Community On-Road airports, including a comparison to 2011 Service Indices. 3.2.1 Regional Airports Service Index Service Index objectives for airports in the Regional classification were developed with the intention of providing all weather service to turbine aircraft over 12,500 pounds. These airports are therefore held to higher standards for runway type (paved), strength (30,000 pounds single wheel load), length (5,000 feet), lighting (HIRL), and instrument approach minimums than are Community airports. Regional airports are also recommended to have a full parallel taxiway system to improve airport safety and efficiency. Regional airports are recommended to offer fuel sales, have available lease lot and tie-down space, and have passenger shelter and public toilet facilities.