BMH.WS0264.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roinn Cosanta

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 624 Witness Mrs. Mary Flannery Woods, 17 Butterfield Crescent, Rathfarnham, Dublin. Identity. Member of A.O.H. and of Cumann na mBan. Subject. Reminiscences of the period 1895-1924. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File No. S.1901 Form B.S.M.2 Statement by Mrs. Mary Flannery Woods, 17 Butterfield Crescent, Rathfarnham, Dublin. Memories of the Land League and Evictions. I am 76 years of age. I was born in Monasteraden in County Sligo about five miles from Ballaghaderreen. My first recollections are Of the Lend League. As a little girl I used to go to the meetings of Tim Healy, John Dillon and William O'Brien, and stand at the outside of the crowds listening to the speakers. The substance of the speeches was "Pay no Rent". It people paid rent, organizations such as the "Molly Maguire's" and the "Moonlighters" used to punish them by 'carding them', that means undressing them and drawing a thorny bush over their bodies. I also remember a man, who had a bit of his ear cut off for paying his rent. He came to our house. idea was to terrorise them. Those were timid people who were afraid of being turned out of their holdings if they did not pay. I witnessed some evictions. As I came home from school I saw a family sitting in the rain round a small fire on the side of the road after being turned out their house and the door was locked behind them. -

The Kent Family & Cork's Rising Experience

The Kent Family & Cork’s Rising Experience By Mark Duncan In the telling of the Easter 1916 story, Cork appears only the margins. The reasons for this are not too hard to comprehend. Here was a county that had thought about mounting insurrection, then thought better of it. This failure to mobilise left an unpleasant aftertaste, becoming, for some at least, a source of abiding regret which bordered on embarrassment. It left behind it, Liam de Roiste, the Gaelic scholar and then leading local Irish Volunteer, wistfully recalled, a trail of ‘heart burning, disappointments, and some bitter feelings. The hour had come and we, in Cork, had done nothing.’1 In the circumstances, the decision to remain inactive – encouraged by the intervention by local bishop Daniel Colohan and Cork City Lord Mayor W. T. Butterfield - was an understandable one, wise even in view of the failed landing of German arms on board the Aud and the confusion created by the countermanding order of Eoin Mac Neill which delayed for a day, and altered completely, the character of the Rising that eventually took place.2 In any case, with Dublin planned as the operational focus of the Rising, Cork was hardly alone in remaining remote from the fray. Yes, trouble flared in Galway, in Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford and in Ashbourne, Co. Meath, but so few were these locations and so limited was the fighting that it served only to underline the failure of the insurgents to ignite a wider rebellion across provincial Ireland. For much of the country, the Rising of 1916 was experienced only in the heavy-handed and occasionally brutal backlash to it. -

Irish History Links

Irish History topics pulled together by Dan Callaghan NC AOH Historian in 2014 Athenry Castle; http://www.irelandseye.com/aarticles/travel/attractions/castles/Galway/athenry.shtm Brehon Laws of Ireland; http://www.libraryireland.com/Brehon-Laws/Contents.php February 1, in ancient Celtic times, it was the beginning of Spring and later became the feast day for St. Bridget; http://www.chalicecentre.net/imbolc.htm May 1, Begins the Celtic celebration of Beltane, May Day; http://wicca.com/celtic/akasha/beltane.htm. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ February 14, 269, St. Valentine, buried in Dublin; http://homepage.eircom.net/~seanjmurphy/irhismys/valentine.htm March 17, 461, St. Patrick dies, many different reports as to the actual date exist; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11554a.htm Dec. 7, 521, St. Columcille is born, http://prayerfoundation.org/favoritemonks/favorite_monks_columcille_columba.htm January 23, 540 A.D., St. Ciarán, started Clonmacnoise Monastery; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04065a.htm May 16, 578, Feast Day of St. Brendan; http://parish.saintbrendan.org/church/story.php June 9th, 597, St. Columcille, dies at Iona; http://www.irishcultureandcustoms.com/ASaints/Columcille.html Nov. 23, 615, Irish born St. Columbanus dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/04137a.htm July 8, 689, St. Killian is put to death; http://allsaintsbrookline.org/celtic_saints/killian.html October 13, 1012, Irish Monk and Bishop St. Colman dies; http://www.stcolman.com/ Nov. 14, 1180, first Irish born Bishop of Dublin, St. Laurence O'Toole, dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/09091b.htm June 7, 1584, Arch Bishop Dermot O'Hurley is hung by the British for being Catholic; http://www.exclassics.com/foxe/dermot.htm 1600 Sept. -

BMH.WS1737.Pdf

ROINN COSANTA BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21 STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1,757. Witness Seamus Fitzgerald, "Carrigbeg", Summerhill. CORK. Identity. T.D. in 1st Dáll Éireann; Chairman of Parish Court, Cobh; President of East Cork District Court.Court. Subject.District 'A' Company (Cobh), 4th Battn., Cork No. 1 Bgde., - I.R.A., 1913 1921. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil. File No S. 3,039. Form BSM2 P 532 10006-57 3/4526 BUREAUOFMILITARYHISTORY1913-21 BURO STAIREMILEATA1913-21 No. W.S. ORIGINAL 1737 STATEMENT BY SEAMUS FITZGERALD, "Carrigbeg". Summerhill. Cork. On the inauguration of the Irish Volunteer movement in Dublin on November 25th 1913, I was one of a small group of Cobh Gaelic Leaguers who decided to form a unit. This was done early in l9l4, and at the outbreak of the 1914. War Cobh had over 500 Volunteers organised into six companies, and I became Assistant Secretary to the Cobh Volunteer Executive at the age of 17 years. When the split occurred in the Irish Volunteer movement after John Redmond's Woodenbridge recruiting speech for the British Army - on September 20th 1914. - I took my stand with Eoin MacNeill's Irish Volunteers and, with about twenty others, continued as a member of the Cobh unit. The great majority of the six companies elected, at a mass meeting in the Baths Hall, Cobh, to support John Redmond's Irish National Volunteers and give support to Britain's war effort. The political feelings of the people and their leaders at this tint, and the events which led to this position in Cobh, so simply expressed in the foregoing paragraphs, and which position was of a like pattern throughout the country, have been given in the writings of Stephen Gwynn, Colonel Maurice Moore, Bulmer Hobson, P.S. -

Secret Societies and the Easter Rising

Dominican Scholar Senior Theses Student Scholarship 5-2016 The Power of a Secret: Secret Societies and the Easter Rising Sierra M. Harlan Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2016.HIST.ST.01 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Harlan, Sierra M., "The Power of a Secret: Secret Societies and the Easter Rising" (2016). Senior Theses. 49. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2016.HIST.ST.01 This Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POWER OF A SECRET: SECRET SOCIETIES AND THE EASTER RISING A senior thesis submitted to the History Faculty of Dominican University of California in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts in History by Sierra Harlan San Rafael, California May 2016 Harlan ii © 2016 Sierra Harlan All Rights Reserved. Harlan iii Acknowledgments This paper would not have been possible without the amazing support and at times prodding of my family and friends. I specifically would like to thank my father, without him it would not have been possible for me to attend this school or accomplish this paper. He is an amazing man and an entire page could be written about the ways he has helped me, not only this year but my entire life. As a historian I am indebted to a number of librarians and researchers, first and foremost is Michael Pujals, who helped me expedite many problems and was consistently reachable to answer my questions. -

Con Colbert: 16Lives Free

FREE CON COLBERT: 16LIVES PDF John O'Callaghan | 256 pages | 31 Jan 2016 | O'Brien Press Ltd | 9781847173348 | English | Dublin, Ireland New Books - New Book Review - New Book Reviews - New Books Reviews Paul Barrett is a Con Colbert: 16lives fourth-year student at the University of Limerick, Ireland, majoring in English and History. The youngest person executed as part of the Rising, Con Colbert cuts a unique figure in the history of the Irish nation. Limerick Leader. Con Colbert: 16lives main argument that will encompass this article is that Con Colbert was executed in the rising, because of his high profile rather than Colbert deliberately taking the position of his commanding officer Seamus Murphy. A historiographical section concerning contemporary ideas surrounding this question will also be delved into. The proceedings of the court-martial are crucial here in delving into the mind of the British authorities to try to see their reasoning behind the execution. Much of the research done on this topic previously, is considerably uniform in their opinion of Colbert's execution. However, not much research has been done on the activities by Colbert that would have made him well known to the British authorities at the time. Firstly, much has been deliberated regarding Con Colbert, as well as the executions in The literature has discussed the fact that Colbert along with ten others, were not officially acknowledged until the start of this century. This was covered in an article in the Sunday Times inas the author indicates that this shows the disdain the British authorities had for these men. -

Volunteer Women: Militarized Femininity in the 1916 Easter Rising

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons War and Society (MA) Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-20-2019 Volunteer Women: Militarized Femininity in the 1916 Easter Rising Sasha Conaway Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/war_and_society_theses Part of the Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Conaway, Sasha. Volunteer Women: Militarized Femininity in the 1916 Easter Rising. 2019. Chapman University, MA Thesis. Chapman University Digital Commons, https://doi.org/10.36837/chapman.000079 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in War and Society (MA) Theses by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volunteer Women: Militarized Femininity in the 1916 Easter Rising A Thesis by Sasha Conaway Chapman University Orange, CA Wilkinson College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in War and Society May 2019 Committee in Charge Jennifer Keene, Ph.D., Chair Charissa Threat, Ph.D. John Emery, Ph. D. May 2019 Volunteer Women: Militarized Femininity in the 1916 Easter Rising Copyright © 2019 by Sasha Conaway iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my parents, Elda and Adam Conaway, for supporting me in pursuit of my master’s degree. They provided useful advice when tackling such a large project and I am forever grateful. I would also like to thank my advisor, Dr. -

Downloaded from the 1000 Genomes Website

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/076992; this version posted October 8, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. 1 The Identification of a 1916 Irish Rebel: New Approach for Estimating 2 Relatedness From Low Coverage Homozygous Genomes 3 4 Daniel Fernandes1,2,6*, Kendra Sirak1,3,6, Mario Novak1,4, John Finarelli5,6, John Byrne7, Edward 5 Connolly8, Jeanette EL Carlsson5,9, Edmondo Ferretti9, Ron Pinhasi1,6, Jens Carlsson5,9 6 7 1 School of Archaeology, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Republic of Ireland 8 2 CIAS, Department of Life Sciences, University of Coimbra, 3000-456 Coimbra, Portugal 9 3 Department of Anthropology, Emory University, 201 Dowman Dr., Atlanta, GA 30322, United States of 10 America 11 4 Institute for Anthropological Research, Ljudevita Gaja 32, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 12 5 School of Biology and Environment Science, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Republic of 13 Ireland 14 6 Earth Institute, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Republic of Ireland 15 7 National Forensic Coordination Office, Garda Technical Bureau, Garda Headquarters, Phoenix Park, 16 Dublin 8, Republic of Ireland. 17 8 Forensic Science Ireland, Garda Headquarters, Phoenix Park, Dublin 8, Republic of Ireland 18 9 Area 52 Research Group, School of Biology and Environment Science, University College Dublin, 19 Dublin 4, Republic of Ireland 20 * [email protected] 21 22 ABSTRACT 23 Thomas Kent was an Irish rebel who was executed by British forces in the aftermath of the Easter Rising 24 armed insurrection of 1916 and buried in a shallow grave on Cork prison’s grounds. -

Easter Rising Heroes 1916

Cead mile Failte to the 3rd in a series of 1916 Commemorations sponsored by the LAOH and INA of Cleveland. Tonight we honor all the Men and Women who had a role in the Easter 1916 Rising whether in the planning or active participation.Irish America has always had a very important role in striving for Irish Freedom. I would like to share a quote from George Washington "May the God in Heaven, in His justice and mercy, grant thee more prosperous fortunes and in His own time, cause the sun of Freedom to shed its benign radiance on the Emerald Isle." 1915-1916 was that time. On the death of O'Donovan Rossa on June 29, 1915 Thomas Clarke instructed John Devoy to make arrangements to bring the Fenian back home. I am proud that Ellen Ryan Jolly the National President of the LAAOH served as an Honorary Pallbearer the only woman at the Funeral held in New York. On August 1 at Glasnevin the famous oration of Padraic Pearse was held at the graveside. We choose this week for this presentation because it was midway between these two historic events as well as being the Anniversary week of Constance Markeivicz death on July 15,1927. She was condemned to death in 1916 but as a woman her sentence was changed to prison for life. And so we remember those executed. We remember them in their own words and the remembrances of others. Sixteen Dead Men by WB Yeats O but we talked at large before The Sixteen men were shot But who can talk of give and take, What should be and what not While those dead men are loitering there To stir the boiling pot? You say that -

What Was It Like for Children at School in 1916?

IRELAND IN 1916 IRELAND IN 1916 DISCOVER Children in Dublin collecting firewood from the ruined buildings damaged in the Easter Rising. GETTY IMAGES A barefooted boy with the crowds attending an inquest into the shooting in July 1914 at Bachelor’s Walk by the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, where three people were killed and thirty injured. GETTY IMAGES What was life like in the Ireland of 1916? What was it like RELAND was a nation divided in I1916, with nationalists preparing for rebellion at a time when tens of thousands of Irishmen had joined the British Army and set sail for Europe to fight for the king. Dublin was considered the second city for children at of the British Empire after London, but many people were struggling to survive. Professionals, civil servants and the rich were abandoning the grand Georgian houses on Dublin’s Mountjoy Square, North Great George’s Street and Henrietta Street for the new suburbs, school in 1916? and their former homes turned into Students of Castlelyons N.S. with their tenements. Thomas Kent Projects: Oscar Hallinan, Jobs were scarce, and everybody Learning was a tough experience, says Emma Dineen Charlotte Kent and Dara Spillane with dreamed of working for a ‘good’ Abie Bryan and Olivia Beausang (front). employer like Guinness. Most workers were unskilled, and MICHAEL MacSWEENEY/PROVISION T may come as a surprise to pupils Today, every teacher must be fully- So although there were plans to really Dublin’s slums were considered among today but 100 years ago Irish was not qualified to teach in primary school. -

Eamonn Ceannt

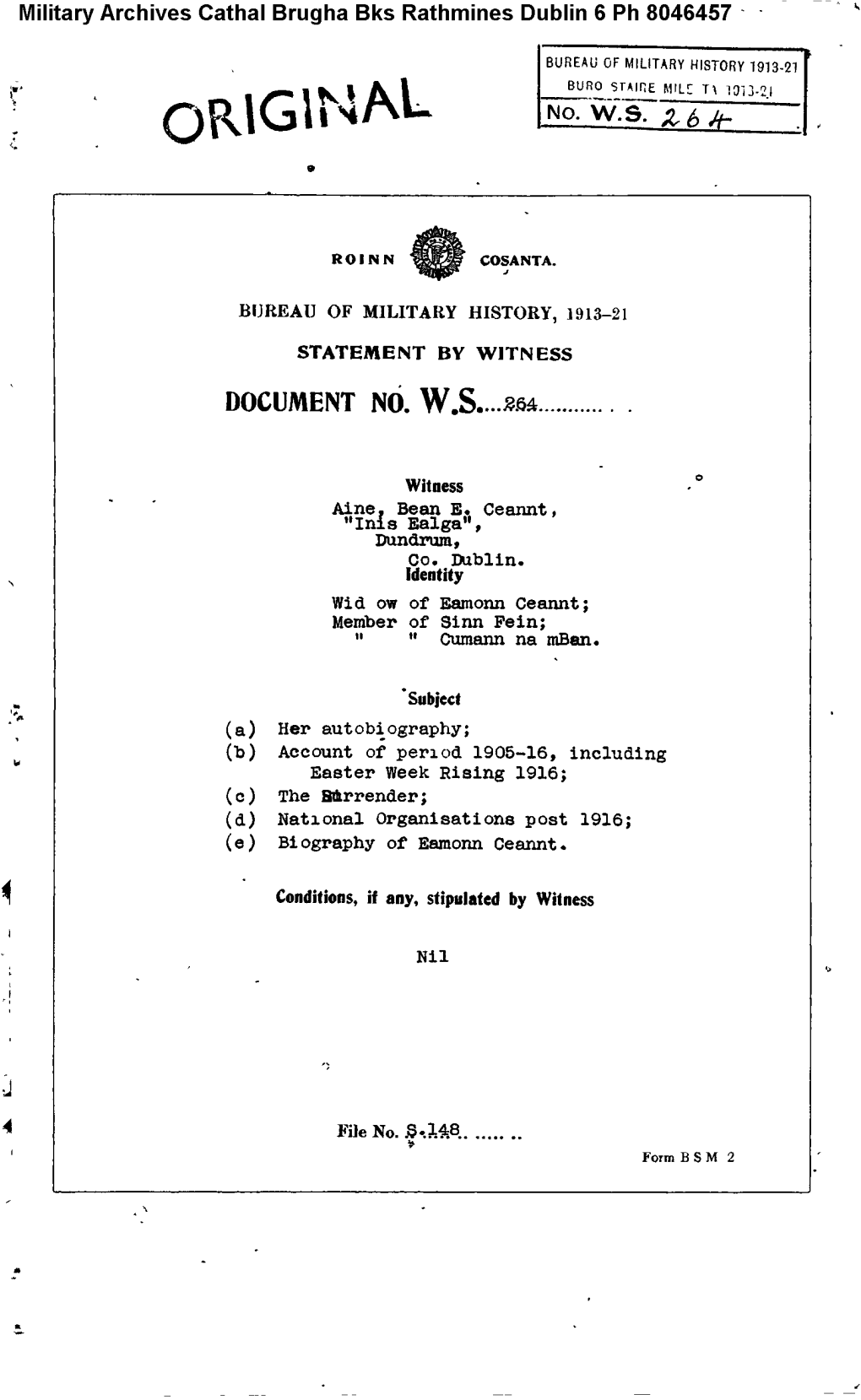

4. The seven members of the Provisional Government 4.5. Éamonn Ceannt Éamonn Ceannt, member of the Provisional Government of the Irish Republic and commandant of the 4th Battalion of the Irish Volunteers. Éamonn Ceannt (1881-1916) was born Edward Thomas Kent in the police barracks at Ballymoe, Co. Galway, the son of James Kent, an officer in the Royal Irish Constabulary, and his wife, Joanne Galway. James Kent was transferred to Ardee, Co. Louth, where Éamonn attended the De La Salle national school, becoming an altar boy—he remained a devout Catholic all his life. The family next moved to Drogheda, where he attended the Christian Brothers’ school at Sunday’s Gate. Finally, on the father’s retirement in 1892, the family settled in Dublin; there, Éamonn attended the O’Connell Schools on North Richmond Street run by the Christian Brothers, and University College, Dublin. He found employment with Dublin Corporation in the rates department and later the city treasury office. Éamonn was deeply interested in Irish cultural activities, especially music. In 1899 he joined the central branch of the Gaelic League, where he met Patrick Pearse and Eoin MacNeill. He became a fluent Irish speaker and adopted the Irish form of his name by which he was always known afterwards. He taught Irish part-time at various Gaelic League branches, gaining a reputation as an inspiring teacher. He played a number of musical instruments, the Irish war and uileann pipes being his particular favourites. In February 1900 he was involved with Edward Martyn in setting up the Dublin Pipers’ Club, of which he became secretary. -

O'driscoll, C. (2017) Knowing and Forgetting the Easter 1916 Rising

O'Driscoll, C. (2017) Knowing and forgetting the Easter 1916 Rising. Australian Journal of Politics and History, 63(3), pp. 419-429. (doi:10.1111/ajph.12371) There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. This is the peer-reviewed version of the following article: O'Driscoll, C. (2017) Knowing and forgetting the Easter 1916 Rising. Australian Journal of Politics and History, 63(3), pp. 419-429, which has been published in final form at 10.1111/ajph.12371. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/149937/ Deposited on: 17 October 2017 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Knowing and Forgetting the Easter 1916 Rising Cian O’Driscoll University of Glasgow [email protected] Introduction “Life springs from death; and from the graves of patriot men and women spring living nations.”1 The Easter Rising took place on Easter Monday, the 24th April, 1916. Focused primarily on a set of strategic locations in the heart of Dublin, it was directed by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and carried out by a militant force of no more than 1,600 men and women. The Rising began when rebels seized several buildings in Dublin city-centre, including the General Post Office (GPO), from where Patrick Pearse later that day proclaimed the establishment of the Irish Republic.