The Kent Family & Cork's Rising Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BMH.WS1737.Pdf

ROINN COSANTA BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21 STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1,757. Witness Seamus Fitzgerald, "Carrigbeg", Summerhill. CORK. Identity. T.D. in 1st Dáll Éireann; Chairman of Parish Court, Cobh; President of East Cork District Court.Court. Subject.District 'A' Company (Cobh), 4th Battn., Cork No. 1 Bgde., - I.R.A., 1913 1921. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil. File No S. 3,039. Form BSM2 P 532 10006-57 3/4526 BUREAUOFMILITARYHISTORY1913-21 BURO STAIREMILEATA1913-21 No. W.S. ORIGINAL 1737 STATEMENT BY SEAMUS FITZGERALD, "Carrigbeg". Summerhill. Cork. On the inauguration of the Irish Volunteer movement in Dublin on November 25th 1913, I was one of a small group of Cobh Gaelic Leaguers who decided to form a unit. This was done early in l9l4, and at the outbreak of the 1914. War Cobh had over 500 Volunteers organised into six companies, and I became Assistant Secretary to the Cobh Volunteer Executive at the age of 17 years. When the split occurred in the Irish Volunteer movement after John Redmond's Woodenbridge recruiting speech for the British Army - on September 20th 1914. - I took my stand with Eoin MacNeill's Irish Volunteers and, with about twenty others, continued as a member of the Cobh unit. The great majority of the six companies elected, at a mass meeting in the Baths Hall, Cobh, to support John Redmond's Irish National Volunteers and give support to Britain's war effort. The political feelings of the people and their leaders at this tint, and the events which led to this position in Cobh, so simply expressed in the foregoing paragraphs, and which position was of a like pattern throughout the country, have been given in the writings of Stephen Gwynn, Colonel Maurice Moore, Bulmer Hobson, P.S. -

Downloaded from the 1000 Genomes Website

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/076992; this version posted October 8, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. 1 The Identification of a 1916 Irish Rebel: New Approach for Estimating 2 Relatedness From Low Coverage Homozygous Genomes 3 4 Daniel Fernandes1,2,6*, Kendra Sirak1,3,6, Mario Novak1,4, John Finarelli5,6, John Byrne7, Edward 5 Connolly8, Jeanette EL Carlsson5,9, Edmondo Ferretti9, Ron Pinhasi1,6, Jens Carlsson5,9 6 7 1 School of Archaeology, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Republic of Ireland 8 2 CIAS, Department of Life Sciences, University of Coimbra, 3000-456 Coimbra, Portugal 9 3 Department of Anthropology, Emory University, 201 Dowman Dr., Atlanta, GA 30322, United States of 10 America 11 4 Institute for Anthropological Research, Ljudevita Gaja 32, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 12 5 School of Biology and Environment Science, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Republic of 13 Ireland 14 6 Earth Institute, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Republic of Ireland 15 7 National Forensic Coordination Office, Garda Technical Bureau, Garda Headquarters, Phoenix Park, 16 Dublin 8, Republic of Ireland. 17 8 Forensic Science Ireland, Garda Headquarters, Phoenix Park, Dublin 8, Republic of Ireland 18 9 Area 52 Research Group, School of Biology and Environment Science, University College Dublin, 19 Dublin 4, Republic of Ireland 20 * [email protected] 21 22 ABSTRACT 23 Thomas Kent was an Irish rebel who was executed by British forces in the aftermath of the Easter Rising 24 armed insurrection of 1916 and buried in a shallow grave on Cork prison’s grounds. -

Miscellaneous Notes on Republicanism and Socialism in Cork City, 1954–69

MISCELLANEOUS NOTES ON REPUBLICANISM AND SOCIALISM IN CORK CITY, 1954–69 By Jim Lane Note: What follows deals almost entirely with internal divisions within Cork republicanism and is not meant as a comprehensive outline of republican and left-wing activities in the city during the period covered. Moreover, these notes were put together following specific queries from historical researchers and, hence, the focus at times is on matters that they raised. 1954 In 1954, at the age of 16 years, I joined the following branches of the Republican Movement: Sinn Féin, the Irish Republican Army and the Cork Volunteers’Pipe Band. The most immediate influence on my joining was the discovery that fellow Corkmen were being given the opportunity of engag- ing with British Forces in an effort to drive them out of occupied Ireland. This awareness developed when three Cork IRA volunteers were arrested in the North following a failed raid on a British mil- itary barracks; their arrest and imprisonment for 10 years was not a deterrent in any way. My think- ing on armed struggle at that time was informed by much reading on the events of the Tan and Civil Wars. I had been influenced also, a few years earlier, by the campaigning of the Anti-Partition League. Once in the IRA, our initial training was a three-month republican educational course, which was given by Tomas Óg MacCurtain, son of the Lord Mayor of Cork, Tomas MacCurtain, who was murdered by British forces at his home in 1920. This course was followed by arms and explosives training. -

Easter Rising Heroes 1916

Cead mile Failte to the 3rd in a series of 1916 Commemorations sponsored by the LAOH and INA of Cleveland. Tonight we honor all the Men and Women who had a role in the Easter 1916 Rising whether in the planning or active participation.Irish America has always had a very important role in striving for Irish Freedom. I would like to share a quote from George Washington "May the God in Heaven, in His justice and mercy, grant thee more prosperous fortunes and in His own time, cause the sun of Freedom to shed its benign radiance on the Emerald Isle." 1915-1916 was that time. On the death of O'Donovan Rossa on June 29, 1915 Thomas Clarke instructed John Devoy to make arrangements to bring the Fenian back home. I am proud that Ellen Ryan Jolly the National President of the LAAOH served as an Honorary Pallbearer the only woman at the Funeral held in New York. On August 1 at Glasnevin the famous oration of Padraic Pearse was held at the graveside. We choose this week for this presentation because it was midway between these two historic events as well as being the Anniversary week of Constance Markeivicz death on July 15,1927. She was condemned to death in 1916 but as a woman her sentence was changed to prison for life. And so we remember those executed. We remember them in their own words and the remembrances of others. Sixteen Dead Men by WB Yeats O but we talked at large before The Sixteen men were shot But who can talk of give and take, What should be and what not While those dead men are loitering there To stir the boiling pot? You say that -

The Centenary of the First Dáil 21St January 1919

The Centenary of the First Dáil 21st January 1919 Commemorated by Cork County Council on 21st January 2019 at a Special Meeting convened by the Mayor of the County of Cork Cllr. Patrick Gerard Murphy Comóradh Céad Bliain den Chéad Dáil An 21 Eanáir, 1919 Tugtha chun cuimhne ag Comhairle Contae Chorcaí Ag tionól speisialta a ghairm Méara Chontae Chorcaí an Comhairleoir Patrick Gerard Murphy FOREWORD RéamhRá BY MAYOR OF THE COUNTY OF ó Méara Chontae Chorcaí, CORK CLLR. PATRICK GERARD an Comhairleoir Patrick Gerard Murphy, MURPHY AND agus an Príomhfheidhmeannach CHIEF EXECUTIVE OF CORK de Comhairle Contae Chorcaí COUNTY COUNCIL TIM LUCEY an tUasal Tim Lucey As citizens of Ireland, today is a special Is lá speisialta é seo duinn mar day when we commemorate the Shaoránaigh na hÉireann, nuair a centenary of the First Dáil, which took chuimhnímid comóradh céad bhliain an place in the Mansion House in Dublin Chéad Dáil, a tharla i dTeach an Ard- on Tuesday, the 21st of January, 1919. Mhéara i mBaile Átha Cliath Dé Máirt, an 21ú Eanáir, 1919. This was a most momentous occasion, Ba seo ócáid an-tábhachtach, rud a chuir which resolutely conveyed Ireland’s in iúl go diongbháilte an chreideamh firm belief in the ownership of its own laidir atá ag Éireann in úinéireacht a destiny by having a government of the chinniúint féin trí rialtas na daoine, ag na people, by the people, for the people. daoine, ar son na daoine. Is lá a bhí ann It was a day when Ireland stood up to nuair a sheas Éire suas le chomhaireamh be counted among the Nations of the i measc Náisiún an Domhain - lá a World - a day that draws our attention tharraingíonn ár n-aird leis an bhród with the utmost pride and belief. -

What Was It Like for Children at School in 1916?

IRELAND IN 1916 IRELAND IN 1916 DISCOVER Children in Dublin collecting firewood from the ruined buildings damaged in the Easter Rising. GETTY IMAGES A barefooted boy with the crowds attending an inquest into the shooting in July 1914 at Bachelor’s Walk by the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, where three people were killed and thirty injured. GETTY IMAGES What was life like in the Ireland of 1916? What was it like RELAND was a nation divided in I1916, with nationalists preparing for rebellion at a time when tens of thousands of Irishmen had joined the British Army and set sail for Europe to fight for the king. Dublin was considered the second city for children at of the British Empire after London, but many people were struggling to survive. Professionals, civil servants and the rich were abandoning the grand Georgian houses on Dublin’s Mountjoy Square, North Great George’s Street and Henrietta Street for the new suburbs, school in 1916? and their former homes turned into Students of Castlelyons N.S. with their tenements. Thomas Kent Projects: Oscar Hallinan, Jobs were scarce, and everybody Learning was a tough experience, says Emma Dineen Charlotte Kent and Dara Spillane with dreamed of working for a ‘good’ Abie Bryan and Olivia Beausang (front). employer like Guinness. Most workers were unskilled, and MICHAEL MacSWEENEY/PROVISION T may come as a surprise to pupils Today, every teacher must be fully- So although there were plans to really Dublin’s slums were considered among today but 100 years ago Irish was not qualified to teach in primary school. -

Hunger Strikes by Irish Republicans, 1916-1923 Michael Biggs ([email protected]) University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Hunger Strikes by Irish Republicans, 1916-1923 Michael Biggs ([email protected]) University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Paper prepared for Workshop on Techniques of Violence in Civil War Centre for the Study of Civil War, Oslo August 2004 “It is not those who can inflict the most, but those who can suffer the most who will conquer.” (Terence MacSwiney, 1920) “The country has not had, as yet, sufficient voluntary sacrifice and suffering[,] and not until suffering fructuates will she get back her real soul.” (Ernie O’Malley, 1923) The hunger strike is a strange technique of civil war. Physical suffering—possibly even death—is inflicted on oneself, rather than on the opponent. The technique can be conceived as a paradoxical inversion of hostage-taking or kidnapping, analyzed by Elster (2004). With kidnapping, A threatens to kill a victim B in order to force concessions from the target C; sometimes the victim is also the target. With a hunger strike, the perpetrator is the victim: A threatens to kill A in order to force concessions.1 Kidnappings staged for publicity, where the victim is released unconditionally, are analogous to hunger strikes where the duration is explicitly 1 This brings to mind a scene in the film Blazing Saddles. A black man, newly appointed sheriff, is surrounded by an angry mob intent on lynching him. He draws his revolver and points it to his head, warning them not to move “or the nigger gets it.” This threat allows him to escape. The scene is funny because of the apparent paradox of threatening to kill oneself, and yet that is exactly what hunger strikers do. -

The Archive JOURNAL of the CORK FOLKLORE PROJECT IRIS BHÉALOIDEAS CHORCAÍ ISSN 1649 2943 21 UIMHIR FICHE a HAON

The Archive JOURNAL OF THE CORK FOLKLORE PROJECT IRIS BHÉALOIDEAS CHORCAÍ ISSN 1649 2943 21 UIMHIR FICHE A HAON FREE COPY The Archive 21 | 2017 Contents PROJECT MANAGER 3 Introduction Dr Tomás Mac Conmara No crew cuts or new-fangled styles RESEARCH DIRECTOR 4 Mr. Lucas - The Barber. By Billy McCarthy Dr Clíona O’Carroll A reflection on the Irish language in the Cork Folklore 5 EDITORIAL ADVISOR Project Collection by Dr. Tomás Mac Conmara Dr Ciarán Ó Gealbháin The Loft - Cork Shakespearean Company 6 By David McCarthy EDITORIAL TEAM Dr Tomás Mac Conmara, Dr Ciarán Ó The Cork Folklore Masonry Project 10 By Michael Moore Gealbháin, Louise Madden-O’Shea The Early Days of Irish Television PROJECT RESEARCHERS 14 By Geraldine Healy Kieran Murphy, Jamie Furey, James Joy, Louise Madden O’Shea, David McCarthy, Tomás Mac Curtain in Memory by Dr. Tomás Mac 16 Conmara Mark Foody, Janek Flakus Fergus O’Farrell: A personal reflection GRAPHIC DESIGN & LAYOUT 20 of a Cork music pioneer by Mark Wilkins Dermot Casey 23 Book Reviews PRINTERS City Print Ltd, Cork Boxcars, broken glass and backers: Ballyphehane Oral www.cityprint.ie 24 History Project by Jamie Furey 26 A Taste of Tripe by Kieran Murphy The Cork Folklore Project Northside Community Enterprises Ltd facebook.com/corkfolklore @corkfolklore St Finbarr’s College, Farranferris, Redemption Road, Cork, T23YW62 Ireland phone +353 (021) 422 8100 email [email protected] web www.ucc.ie/cfp Acknowledgements Disclaimer The Cork Folklore Project would like to thank : Dept of Social Protection, The Cork Folklore Project is a Dept of Social Protection funded joint Susan Kirby; Management and staff of Northside Community Enterprises; Fr initiative of Northside Community Enterprises Ltd & Dept of Folklore and John O Donovan, Noreen Hegarty; Roinn an Bhéaloideas / Dept of Folklore Ethnology, University College Cork. -

Eamonn Ceannt

4. The seven members of the Provisional Government 4.5. Éamonn Ceannt Éamonn Ceannt, member of the Provisional Government of the Irish Republic and commandant of the 4th Battalion of the Irish Volunteers. Éamonn Ceannt (1881-1916) was born Edward Thomas Kent in the police barracks at Ballymoe, Co. Galway, the son of James Kent, an officer in the Royal Irish Constabulary, and his wife, Joanne Galway. James Kent was transferred to Ardee, Co. Louth, where Éamonn attended the De La Salle national school, becoming an altar boy—he remained a devout Catholic all his life. The family next moved to Drogheda, where he attended the Christian Brothers’ school at Sunday’s Gate. Finally, on the father’s retirement in 1892, the family settled in Dublin; there, Éamonn attended the O’Connell Schools on North Richmond Street run by the Christian Brothers, and University College, Dublin. He found employment with Dublin Corporation in the rates department and later the city treasury office. Éamonn was deeply interested in Irish cultural activities, especially music. In 1899 he joined the central branch of the Gaelic League, where he met Patrick Pearse and Eoin MacNeill. He became a fluent Irish speaker and adopted the Irish form of his name by which he was always known afterwards. He taught Irish part-time at various Gaelic League branches, gaining a reputation as an inspiring teacher. He played a number of musical instruments, the Irish war and uileann pipes being his particular favourites. In February 1900 he was involved with Edward Martyn in setting up the Dublin Pipers’ Club, of which he became secretary. -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT Quality Enhancement Committee 2017 - 2018 Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................3 Section A: Quality Enhancement Strategy Developments .......................................................................4 1.Summary & Overview ............................................................................................................................4 2. UCC Quality Activities ...........................................................................................................................6 I. Evaluation of Academic Quality Review Process ............................................................................... 6 II. Analysis of Academic Review Recommendations ............................................................................ 12 III. Student Reviewer Digital Badges ................................................................................................. 15 IV. University Student Surveys Board ................................................................................................ 15 V. Quality Review Schedule .................................................................................................................. 17 3. External Quality Developments ......................................................................................................... 19 I. Institutional Review of UCC by Quality & Qualifications Ireland: ................................................... -

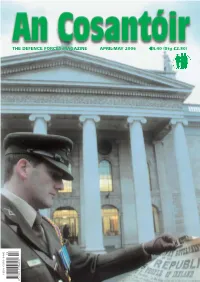

00-AN COS-Apr-May-06

I SSN 0010- 9460 0 3 THE DEFENCEFORCESMAGAZINE 2006 APRIL-MAY THE DEFENCEFORCESMAGAZINE 2006 APRIL-MAY 9 770010 946001 € € 4.40 (Stg£2.80) 4.40 (Stg£2.80) Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street) in flames during the rising. Easter Monday are sent from think is manned by shop in Moore April 24th England. By early insurgents. Street. 1100: Approximately morning the insur- 1,200 Volunteers gents are already Afternoon: Heavy fight- Afternoon: General (including 200 outnumbered four ing continues Maxwell arrives in Citizen Army) to one. British throughout the city. Ireland at 2pm and assemble at troops occupy the British reinforce- takes command of Liberty Hall. Shelbourne Hotel, ments flow in. One the British forces. overlooking insur- such group, the He issues a decla- 1200: Patrick Pearse gent positions in Sherwood ration promising and the HQ group St Stephen’s Forresters, try to tough action of 150 arrive at Green and open take insurgent against the insur- GPO. Pearse fire on the rebels positions around gents. Heavy reads the at first light. Mount Street street fighting con- Proclamation Bridge and incur tinues, particularly from the steps of Early morning: the heaviest casu- heavy in the North the GPO. Insurgents in St alties of the King Street area. Stephen’s Green week’s fighting. 1500: A troop of cavalry take several casu- Saturday ride down alties and are Thursday April 29th Sackville Street forced to evacuate April 27th Morning: Insurgent (O’Connell Street) their positions. The British cordon leaders agree that and incur several The garrison around the GPO and the situation is casualties when moves to the near- the Four Courts is hopeless and sur- fired on by by College of tightened. -

Honoring St. Patrick Convention News

D A T E ® D M A T E R I A L —HIS EMINENCE, PATRICK CARDINAL O’DONNELL of Ireland Vol. LXXXIII No. 2 USPS 373340 March-April 2016 1.50 Honoring St. Patrick In This Issue… Missouri Irish Person of Year James Dailey Wahl & wife, Kathleen Masses, parades and dinner-dances and celebrations of all kinds filled the days of March for AOH and LAOH members throughout the Page 17 country. Here is just a small sampling of the Hibernians on parade. AOH Father Mychal Judge Hudson County, NJ Division 1, from left, Ron Cassidy, Jim Miller, Laurie Lukaszyk, Ray Tierney, Michael Sweeney, Mike Collum, and Jim O’Donnell. Photo George Stampoulos: Respect Life Treasurer-AOH Father Mychal Judge Hudson County, NJ Division 1. See page 12 for more St. Patrick’s Parade photos. Convention News of the Jersey Shore” Buffet and Complimentary Draft Beer at Harrah’s famous “Pool.” Casual Attire. Irish Night Banquet on Wednesday July 13th - “Irish Night” includes a Duet of Chicken and Shrimp. Entertainment provided by the Willie Lynch Band. Business Casual Attire. D.C. President Walsh and NYS Installation Banquet on Thursday July 14th - Choice of: President McSweeney Chicken, Beef or Salmon. Entertainment provided by the Page 10 Eamon Ryan Band. Black Tie Optional. Marching in Maryland A la carte options are also available on line. If you prefer to reserve your package by mail use the application in the Digest. You can even submit and pay for your journal ad on line by clicking on the Journal Ad Book tab. Prefer to submit ad by mail, see journal ad book form in the Digest.