Volunteer Women: Militarized Femininity in the 1916 Easter Rising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republican SINN FÉIN Poblachtach Theobald Wolfe Tone Commemoration Bodenstown, County Kildare

Republican SINN FÉIN Poblachtach Theobald Wolfe Tone Commemoration Bodenstown, County Kildare 2000 ‘Former Republicans have been bought off with palliatives’ Cathleen Knowles McGuirk, Vice President Republican Sinn Féin delivered the oration at the grave of Theobald Wolfe Tone, the founder of Irish Republicanism, on Sunday, June 11 in Bodenstown cemetery, outside Sallins, Co Kildare. The large crowd, led by a colour party carrying the National Flag and contingents of Cumann na mBan and Na Fianna Éireann, as well as the General Tom Maguire Flute Band from Belfast marched the three miles from Sallins Village to the grave of Wolfe Tone at Bodenstown. Contingents from all over Ireland as well as visitors from Britain and the United States took part in the march, which was marshalled by Seán Ó Sé, Dublin. At the graveside of Wolfe Tone the proceedings were chaired by Seán Mac Oscair, Fermanagh, Ard Chomhairle, Republican Sinn Féin who said he was delighted to see the large number of young people from all over Ireland in attendance this year. The ceremony was also addressed by Peig Galligan on behalf of the National Graves Association, who care for Ireland’s patriot graves. Róisín Hayden read a message from Republican Sinn Féin Patron, George Harrison, New York. Republican SINN FÉIN Poblachtach Theobald Wolfe Tone Commemoration Bodenstown, County Kildare “A chairde, a comrádaithe agus a Phoblactánaigh, tá an-bhród orm agus tá sé d’onóir orm a bheith anseo inniu ag uaigh Thiobóid Wolfe Tone, Athair an Phoblachtachais in Éirinn. Fellow Republicans, once more we gather here in Bodenstown churchyard at the grave of Theobald Wolfe Tone, the greatest of the Republican leaders of the 18th century, the most visionary Irishman of his day, and regarded as the “Father of Irish Republicanism”. -

'“War News” Is Published Today Because a Momentous Thing Has

‘The Irish Republic was proclaimed by poster’: the politics of commemorating the Easter Rising Roisín Higgins In a city beset by rumours, the leaders of the Easter Rising quickly began to consolidate their message. On the second day of the insurrection they issued War News, a four page news sheet priced at a penny: ‘“War News” is published today because a momentous thing has happened. … The Irish Republic was proclaimed by poster, which was prominently displayed in Dublin’. War News also carried a report of the statement made by Patrick Pearse that morning which said: The Irish Republic was proclaimed in Dublin on Easter Monday, 24th April, at 12 noon. Simultaneously with the issue of the proclamation of the Provisional Government the Dublin Division of the Army of the Republic, including the Irish Volunteers, Citizen Army, Hibernian Rifles, and other bodies, occupied dominating points in the city. The G.P.O was seized at 12 noon, the Castle was attacked at the same moment, and shortly afterwards the Four Courts were occupied. 1 Two things are striking about this account of the events of Easter Monday. Firstly, there is a very clear attempt to specify the exact moment of origin - to convey a sense of absolute alignment - and, secondly, there is no reference to the Proclamation having been read aloud. The Irish Republic was proclaimed not by Pearse but by poster. Therefore, even though a considerable amount of attention was being paid to how the Easter Rising should be recorded and remembered, the most powerful feature of its subsequent commemorative ritual was overlooked. -

Roinn Cosanta

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 624 Witness Mrs. Mary Flannery Woods, 17 Butterfield Crescent, Rathfarnham, Dublin. Identity. Member of A.O.H. and of Cumann na mBan. Subject. Reminiscences of the period 1895-1924. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File No. S.1901 Form B.S.M.2 Statement by Mrs. Mary Flannery Woods, 17 Butterfield Crescent, Rathfarnham, Dublin. Memories of the Land League and Evictions. I am 76 years of age. I was born in Monasteraden in County Sligo about five miles from Ballaghaderreen. My first recollections are Of the Lend League. As a little girl I used to go to the meetings of Tim Healy, John Dillon and William O'Brien, and stand at the outside of the crowds listening to the speakers. The substance of the speeches was "Pay no Rent". It people paid rent, organizations such as the "Molly Maguire's" and the "Moonlighters" used to punish them by 'carding them', that means undressing them and drawing a thorny bush over their bodies. I also remember a man, who had a bit of his ear cut off for paying his rent. He came to our house. idea was to terrorise them. Those were timid people who were afraid of being turned out of their holdings if they did not pay. I witnessed some evictions. As I came home from school I saw a family sitting in the rain round a small fire on the side of the road after being turned out their house and the door was locked behind them. -

As of April 15, 2021 Giovanni Abbadessa and Cynthia Carrillo

As of April 15, 2021 Giovanni Abbadessa and Cynthia Carrillo Infante Mary Jane Abbott Elizabeth Achorn Eva Adams Maria Alismail and Hussain Alnasser Loraine and Aaron Allen Megan Allen Mitchell Amazon Smile Susan Spellman Ampe Dave Ananian Stephen and Maryanne Andrew Christopher and Danielle Angelillo Anne Annunziata Arbella Charitable Foundation Anthony and Janine Arria Pietro and Theresa Arria Lawrence Babine Sheila Babine Sheila Badolato Karen Bagshaw Benjamin and Elizabeth Ballard John Balliro Edward and Pia Banzy Rafael Baptista Marco and Kristen Baratta John Barranco Meghan Barrasso Stephen and Erin Barrett Larry Barton and Eliza Alden Maureen Begley Kerry Behrens Bellevue Golf Club Memorial Fund Rose and John Benedetti Chuck Bennett Edward and Barbara Bernis Amy Torres Best and Jimmy Torres Garcia Todd and Shellie Bertolami Billings Heating & Air The Billings Family Joshua Binus Fr. Marc Bishop The Blackbaud Giving Fund Diane Blackerby BNY Mellon Financial Stacey Boczenowski Boston Scientific Employee Giving Louis and Shannon Bottari Sam Bouboulis and Lori Stranz Robert and Mary Buccheri Denise Buckley Bowser D. Bramante Eileen Callahan Bredice Jeffrey and Karen Brown Tracie Brown Dan and Linda Browne Jay and Jennifer Buckley Robert and Marie Buckley Andrew Burns Linda Butt Christopher Callahan Mary and Ann Caples Philip and Eleanor Carpenito Greg Case Richard and Deborah Casey Sandra Caso Kathleen Cassell Mrs. Thomas S. Cassell Sheila Cavanaugh and Albert Choy Francis Ceppi Michael Ceppi Steve and Fatima Ceppi Raymond and Donna -

Irish History Links

Irish History topics pulled together by Dan Callaghan NC AOH Historian in 2014 Athenry Castle; http://www.irelandseye.com/aarticles/travel/attractions/castles/Galway/athenry.shtm Brehon Laws of Ireland; http://www.libraryireland.com/Brehon-Laws/Contents.php February 1, in ancient Celtic times, it was the beginning of Spring and later became the feast day for St. Bridget; http://www.chalicecentre.net/imbolc.htm May 1, Begins the Celtic celebration of Beltane, May Day; http://wicca.com/celtic/akasha/beltane.htm. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ February 14, 269, St. Valentine, buried in Dublin; http://homepage.eircom.net/~seanjmurphy/irhismys/valentine.htm March 17, 461, St. Patrick dies, many different reports as to the actual date exist; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11554a.htm Dec. 7, 521, St. Columcille is born, http://prayerfoundation.org/favoritemonks/favorite_monks_columcille_columba.htm January 23, 540 A.D., St. Ciarán, started Clonmacnoise Monastery; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04065a.htm May 16, 578, Feast Day of St. Brendan; http://parish.saintbrendan.org/church/story.php June 9th, 597, St. Columcille, dies at Iona; http://www.irishcultureandcustoms.com/ASaints/Columcille.html Nov. 23, 615, Irish born St. Columbanus dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/04137a.htm July 8, 689, St. Killian is put to death; http://allsaintsbrookline.org/celtic_saints/killian.html October 13, 1012, Irish Monk and Bishop St. Colman dies; http://www.stcolman.com/ Nov. 14, 1180, first Irish born Bishop of Dublin, St. Laurence O'Toole, dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/09091b.htm June 7, 1584, Arch Bishop Dermot O'Hurley is hung by the British for being Catholic; http://www.exclassics.com/foxe/dermot.htm 1600 Sept. -

Going Against the Flow: Sinn Féin´S Unusual Hungarian `Roots´

The International History Review, 2015 Vol. 37, No. 1, 41–58, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2013.879913 Going Against the Flow: Sinn Fein’s Unusual Hungarian ‘Roots’ David G. Haglund* and Umut Korkut Can states as well as non-state political ‘actors’ learn from the history of cognate entities elsewhere in time and space, and if so how and when does this policy knowledge get ‘transferred’ across international borders? This article deals with this question, addressing a short-lived Hungarian ‘tutorial’ that, during the early twentieth century, certain policy elites in Ireland imagined might have great applicability to the political transformation of the Emerald Isle, in effect ushering in an era of political autonomy from the United Kingdom, and doing so via a ‘third way’ that skirted both the Scylla of parliamentary formulations aimed at securing ‘home rule’ for Ireland and the Charybdis of revolutionary violence. In the political agenda of Sinn Fein during its first decade of existence, Hungary loomed as a desirable political model for Ireland, with the party’s leading intellectual, Arthur Griffith, insisting that the means by which Hungary had achieved autonomy within the Hapsburg Empire in 1867 could also serve as the means for securing Ireland’s own autonomy in the first decades of the twentieth century. This article explores what policy initiatives Arthur Griffith thought he saw in the Hungarian experience that were worthy of being ‘transferred’ to the Irish situation. Keywords: Ireland; Hungary; Sinn Fein; home rule; Ausgleich of 1867; policy transfer; Arthur Griffith I. Introduction: the Hungarian tutorial To those who have followed the fortunes and misfortunes of Sinn Fein in recent dec- ades, it must seem the strangest of all pairings, our linking of a party associated now- adays mainly, if not exclusively, with the Northern Ireland question to a small country in the centre of Europe, Hungary. -

'Carry Yourself As Soldiers'

AFTER THE RISING ‘CarrCountess Markievicz arrives at LibertyyHall inyoDublin markingursethe return of Irish Republicanlfprisonersasfrom England insoldiers’June 1917. UCD ARCHIVES PETER PAUL GALLIGAN PAPERS OU are soldiers, and bear Prison in England under the Defence of the yourself as such. Hold Emma Lyons on the fate Realm Act (DORA) “on the ground that she your heads up and march is of hostile association and is reasonably as smartly as if you were suspected of having favoured, promoted on parade — taking no that met the female rebels or assisted an armed insurrection against ‘Y notice of anyone, and his majesty”. Countess Plunkett and Dr looking neither to right or left”. Lynn were also deported to England under These words of advice were offered after the surrender in 1916 DORA, and were to reside at specific by Michael Mallin, commandant of the addresses at Oxford and Bath respectively, garrison occupying St Stephen’s Green, to opposite was very much the case. Helena during their internment, the execution of to be agreed with authorities. the Irish Citizen Army women attached to Molony’s friends joked that her relatively the leaders of the Rising greatly affected Following an announcement by the the garrison, having received the order to brief imprisonment had been “specially them, as they could hear the shots from Home Secretary, Herbert Samuel, in which surrender. As they left the Royal College hard on her” as she had “looked forward to their cells. Winifred Carney recalled that he stated that it was likely that many of of Surgeons, they received “great ovation” it all her life”. -

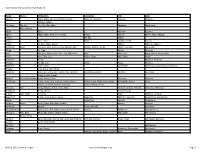

University of Cincinnati Copay Reduction List

University of Cincinnati Copay Reduction List UC Health Physicians Last Name First Name Degree Specialty/Department Abbott Daniel MD Surgery - Surgical Oncology Abbott Susan MD Internal Medicine - General Medicine Abdallah Mouhamad MD Internal Medicine - Cardiology Abdel Karim Nagla MD Internal Medicine - Hem/Onc Abruzzo Todd MD Surgery- Neuro Abu Jawdeh Bassam MD Internal Medicine - Nephrology Adams Brian MD Dermatology Adams Patricia CNS Internal Medicine - Hem/Onc Adeoye Opeolu MD Emergency Medicine - Stroke Team Adler Caleb MD Psychiatry Adler John MD Obstetrics and Gynecology Agabegi Steven MD Orthopaedics Aguado Allison MD Radiology Ahmad Imran MD Internal Medicine - Hospitalists Ahmad Syed MD Surgery - Surgical Oncology Ajebe Epie CNP Psychiatry Alder C. MD Radiology Ali Arshia MD Internal Medicine - Hospitalists Alikhan Mirza MD Dermatology Amfahr Carol CNP Internal Medicine - Hem/Onc Andaluz Norberto MD Surgery - Neuro Angel Victor DO Primary Care Network Anis Mariam MD Internal Medicine - Pulmonary Anjak Ahmad MD Internal Medicine - Hospitalists Anton Christopher MD Radiology Anwar Nadeem MD Internal Medicine - Digestive Disease Apewokin Senu MD Internal Medicine - Infectious Disease Aquino Michael MD Radiology Aragaki Nakahodo Alejandro MD Internal Medicine - Pulmonary Archdeacon Michael MD Orthopaedics Arden James MD Anesthesiology Arif Imran MD Internal Medicine - Cardiology Armentano Ryan PA Emergency Medicine University of Cincinnati Copay Reduction List UC Health Physicians Arnold Lesley MD Psychiatry Arnow Steven DO Ophthalmology -

Secret Societies and the Easter Rising

Dominican Scholar Senior Theses Student Scholarship 5-2016 The Power of a Secret: Secret Societies and the Easter Rising Sierra M. Harlan Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2016.HIST.ST.01 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Harlan, Sierra M., "The Power of a Secret: Secret Societies and the Easter Rising" (2016). Senior Theses. 49. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2016.HIST.ST.01 This Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POWER OF A SECRET: SECRET SOCIETIES AND THE EASTER RISING A senior thesis submitted to the History Faculty of Dominican University of California in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts in History by Sierra Harlan San Rafael, California May 2016 Harlan ii © 2016 Sierra Harlan All Rights Reserved. Harlan iii Acknowledgments This paper would not have been possible without the amazing support and at times prodding of my family and friends. I specifically would like to thank my father, without him it would not have been possible for me to attend this school or accomplish this paper. He is an amazing man and an entire page could be written about the ways he has helped me, not only this year but my entire life. As a historian I am indebted to a number of librarians and researchers, first and foremost is Michael Pujals, who helped me expedite many problems and was consistently reachable to answer my questions. -

Cumann Na Mban: During the Easter Rising

Cumann na mBan: During the Easter Rising Dylan Savoie Junior Division Individual Documentary Process Paper: 500 words Once I learned about National History Day, I immediately wanted to do something related to my Irish heritage seeing as my mother was born in Ireland. In my research, I found the Easter Rising. Now that I had narrowed my selection down, I began to dig deeper, and I came across an Irish women's group, Cumann na mBan, that helped greatly in the Rising but has gone largely unnoticed in history. I tried to have a wide range of research. First, I began by searching for a video about Cumann na mBan. I had found an RTE documentary on the Easter Rising of 1916. It was in that documentary that I came across Fr. Oliver Rafferty, a professor at Boston College. I was able to obtain his email address, contact him, and we had a phone interview. I searched websites and books at my local and Boston Public Library, taking notes and citing them in Noodletools as I went. The Burns Library at Boston College has the most extensive Irish History collection outside of Ireland, so in January, I went there too and was able to obtain many primary sources. In February, I went to Boston College and interviewed Fr. Rafferty in person. I was able to talk with him and combine what I had learned in my research to understand my topic in more depth than I had before. After I collected my research, I decided that my project would be best represented in the form of a documentary. -

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abrev Nicknames

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abrev Nicknames Synonyms Irish Latin Abigail Abby, Abbie, Ab, Gail, Nabby, Gubby, Deborah, Gobinet Gobnait Gobnata Gubbie, Debbie Abraham Ab, Abr, Ab, Abr, Abe, Abby Abraham Abrahame Abra, Abram Adam Edie Adhamh Adamus Agnes Aggie, Aggy, Assie, Inez, Nessa Nancy Aigneis Agnus, Agna, Agneta Ailbhe Elli, Elly Ailbhe Aileen Allie, Lena Eileen Eibhilin, Eibhlin Helena Albert Al, Bert, Albie, Bertie Ailbhe Albertus, Alberti Alexander Alexr Ala, Alec, Alex, Andi, Ec, Lex, Xandra, Ales Alistair, Alaster, Sandy Alastar, Saunder Alexander Alfred Al, Fred Ailfrid Alfredus Alice Eily, Alcy, Alicia, Allie, Elsie, Lisa, Ally, Alica Ellen Ailis, Eilish Alicia, Alecia, Alesia, Alitia Alicia Allie, Elsie, Lisa Alisha, Elisha Ailis, Ailise Alicia Allowshis Allow Aloysius, Aloyisius Aloysius Al, Ally, Lou Lewis Alaois Aloysius Ambrose Brose, Amy Anmchadh Ambrosius, Anmchadus, Animosus Amelia Amy, Emily, Mel, Millie Anastasia Anty, Ana, Stacy, Ant, Statia, Stais, Anstice, Anastatia, Anstace Annstas Anastasia Stasia, Ansty, Stacey Andrew And,Andw,Andrw Andy, Ansey, Drew Aindreas Andreas Ann/Anne Annie, Anna, Ana, Hannah, Hanna, Hana, Nancy, Nany, Nana, Nan, Nanny, Nainseadh, Neans Anna Hanah, Hanorah, Nannie, Susanna Nance, Nanno, Nano Anthony Ant Tony, Antony, Anton, Anto, Anty Anntoin, Antoin, Antoine Antonius, Antonious Archibald Archy, Archie Giolla Easpuig Arthur Artr, Arthr Art, Arty Artur Arcturus, Arturus Augustine Austin, Gus, Gustus, Gussy Augustus Aibhistin, Aguistin Augustinus, Augustinius Austin -

The Main Sites of Activity During the Rising. Dublin City Hall on Easter Monday Captain Seán Connolly of the Irish Citizen Army

7.0 The Main Sites of Activity During the Rising. 7.3 Dublin City Hall On Easter Monday Captain Seán Connolly of the Irish Citizen Army and his company of approximately thirty men convened at Liberty Hall. They were directed to seize and hold City Hall adjoining Dublin Castle. They marched up College Green and Dame Street and occupied City Hall and adjacent buildings, including the Evening Mail premises on the corner of Parliament Street and Dame Street. The ICA contingent in City Hall included Dr Kathleen Lynn and Helena Molony. A party of six men approached the gate of Dublin Castle and shot dead the unarmed policeman on duty, Constable James O’Brien of the Dublin Metropolitan Police, as he tried to close the gate to prevent entry. The party then seized the guardroom, disarming and imprisoning the six soldiers present. In the plans for the Rising, it appears that Dublin Castle was not selected as one of the positions to be commandeered, presumably because it was believed that it was too well guarded. On the day, however, apart from sixty-five wounded service men in the hospital, there were fewer than twenty-five soldiers on duty. Moreover, at the very time the ICA men captured the guardroom, the under-secretary, Sir Matthew Nathan and two of his officials were in conference in the Castle; unaware that the Rising had actually broken out they were arranging for the arrest of those they suspected of being involved in planning an insurrection. It would certainly have been a tremendous coup for the Provisional Government if Dublin Castle, the symbol of British dominion, and one of 1 the most senior offcials of the British administration were captured.