Conference Presentation Reference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Railways of the MENA Region, Tools of National and Foreign Policy

DHEEI – Mediterranean Studies Railways of the MENA Region, tools of national and foreign policy Master’s Thesis submitted by GALLOY Théophile Academic year: 2018-2019 Thesis Supervisor: Dr. Silvia Colombo Acknowledgements I wish to express my appreciation to my family, my co-students and CIFE for their valuable support throughout this year. I am also very grateful for the advice given by my fantastic supervisor Dr. Silvia Colombo, who has kindly dedicated some time to read, correct and advise me on my work, whilst allowing me to remain creative in my approach and research. I would also like to extend my thanks to my previous manager, Mr. Stephane Downes, and my previous employer, Mr. Stephane Rambaud-Measson, for opening me the doors of the railway industry and for passing on to me their knowledge and passion for this fascinating sector. I would also like to thank Dr. Ayadi Soufiane, the surgeon who successfully removed my infected appendix in Tunis, which allowed me to continue my work unimpeded. 2 Acknowledgements_____________________________________________________2 Table of Contents_______________________________________________________3 Introduction___________________________________________________________4 Part I: Understanding the political benefits of railway infrastructures______________6 1) The economic and social benefits of rail_____________________________6 2) Rail as a nation building infrastructure, a tool of power________________12 3) Rail as a region building infrastructure, a tool of integration____________19 Part II: -

Doing Business in the United Arab Emirates

DOING BUSINESS IN THE UAE Dubai, © Sophie James DOING BUSINESS IN THE UNITED ARAB EMIRATES Abu Dhabi, © Philip Lange DOING BUSINESS IN THE UAE INTRODUCTION Since the discovery of oil in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) more than 40 years ago, the country has undergone a profound transformation to a modern state with a high standard of living. This growth was for a large extent driven by income from oil and gas resources. Today the UAE is more than an economy based on oil and gas. Successful efforts at economic diversification in trade, logistics, banking, tourism, real estate and manufacturing have sig- nificantly reduced the portion of GDP based on oil and gas output. The diversified growth environment that is being created in the UAE provides abundant business opportunities. The UAE’s liberal climate towards foreign cooperation, investment and modernisation has prompted extensive diplomatic and commercial relations with other countries. With its prime geographical location at the crossroads of the major Western and Eastern economies, its established and efficient air and sea connections and developed infrastructure, the UAE is an exciting prospect for any business looking to establish a foothold, or expand, in the MENA region or wider Africa and Asia. In 2012, mutual trade between the Netherlands and the UAE was worth more than 3,2 billion euros according to figures from Statistics Netherlands (CBS). Total trade between the Neth- erlands and the Gulf region (Qatar, UAE, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Kuwait and Bahrain) was worth over 14 billion euros. While the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is the Netherlands’ biggest trading partner in the Gulf region (6.9 billion euros), the UAE is the largest export market (nearly 2.4 billion euros). -

Adept Environmental Consultancy

ADEPT ENVIRONMENTAL CONSULTANCY COMPANY PROFILE Contact Senathipathi Kalimuthu (Former Senior Environmental Scientist – RTI International, Abu Dhabi) M-2, Plot No. C-14, Shabiya-10 (ME-10) Mohammed Bin Zayed City, Abu Dhabi, UAE. Tel.: +971 25548777 Mob.: +971 567535789 Email: [email protected] Web Site: https://adepteco.com About Us Adept is a multidisciplinary environmental consulting firm specialized in environmental, health and safety field and providing services in variety of sectors including industries, oil and gas chemical, petrochemical, industrial and infrastructure development projects. Our consultants have excellent work experience with environmental regulatory authority and various international environmental, Health and Safety projects. Our team’s clear vision and core values allow Adept to continually deliver the highest quality of service and value to our clients across all of our consulting engagements. This has been achieved through the implementation ISO 9001-2015, ISO 14001-2015 and OSHAS 18001- 2007. We work with our clients to develop sustainable, practical and ethical solutions to the environmental challenges they face and add value to our client’s businesses by delivering excellence and innovation. Our team aims to assist our clients to ensure that the environment, workplace and communities in which they operate are mutually beneficial and safe. Mission Adept Environmental Consultancy is committed to provide cost effective, innovative, and sustainable Environment, Health and Safety (EHS) consulting services that address our client’s requirements and comply with international best practices. Vision Through achieving commercial success and full satisfaction for our clients, we seek to build a quality and sustainable future for all the stakeholders in the community by applying analytical research and providing innovative solution. -

The Association Between Benefits Realization and Dubai/UAE Infrastructure Development Projects Outcomes”

“The Association between Benefits Realization and Dubai/UAE Infrastructure Development Projects Outcomes” "العﻻقة بين تحقيق الفوائد ونتائج مشاريع البنية التحتية لدبي / اﻹمارات العربية المتحدة" by AHMAD ABDULRAHMAN ALSHARIF A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MSc PROJECT MANAGEMENT at The British University in Dubai December 2018 DECLARATION I warrant that the content of this research is the direct result of my own work and that any use made in it of published or unpublished copyright material falls within the limits permitted by international copyright conventions. I understand that a copy of my research will be deposited in the University Library for permanent retention. I hereby agree that the material mentioned above for which I am author and copyright holder may be copied and distributed by The British University in Dubai for the purposes of research, private study or education and that The British University in Dubai may recover from purchasers the costs incurred in such copying and distribution, where appropriate. I understand that The British University in Dubai may make a digital copy available in the institutional repository. I understand that I may apply to the University to retain the right to withhold or to restrict access to my thesis for a period which shall not normally exceed four calendar years from the congregation at which the degree is conferred, the length of the period to be specified in the application, together with the precise reasons for making that application. _______________________ Signature of the student COPYRIGHT AND INFORMATION TO USERS The author whose copyright is declared on the title page of the work has granted to the British University in Dubai the right to lend his/her research work to users of its library and to make partial or single copies for educational and research use. -

Abu Dhabi PROJECTS at a Glance

Abu Dhabi Abu Dhabi ABU DHABI PROJECTS AT A GLANCE Package name Owner Status $ million* Consultant Principal contractor Start date End date Abu Dhabi Central Market Redevelopment Aldar Properties Construction 1,875 Foster + Partners-EC Harris Arabian Construction Company (ACC)-Mushrif Trading & Contracting Company Q2-2007 Q1-2014 Abu Dhabi International Airport – Midfield Terminal Complex Abu Dhabi Airport Company (Adac)-Scadia Construction 4,000 Arup-Kohn Pederson Fox Associates (KPF) Consolidated Contractors Company (CCC), TAV and Arabtec Q2-2012 Q4-2016 Abu Dhabi International Airport Expansion – Overview Adac-Scadia EPC 7,080 Skidmore Owings & Merrill (SOM)-Aeroport de Paris-Halcrow-KPF Al Habtoor Engineering Enterprises-Al Jaber & Partners Construction & – Q4-2015 Energy-Murray & Roberts-Oderbrecht Abu Dhabi Metro Abu Dhabi Department of Transport (Dot) Design 7,000 Parsons Brinckerhoff-Aecom-DP Architects Not yet appointed Q3-2014 Q1-2019 Adnoc Headquarters Complex Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (Adnoc) Construction 1,000 HOK-Hill International Six Construct Q2-2010 Q4-2013 Al Falah Community Development Aldar Properties Construction 2,500 Hyder Consulting Middle East-Road Transport and Civil Engineering Al Jaber Engineering Services-Ghantoot Transport & General Contracting- Q1-2009 Q4-2015 Consultants-Urbis Limited-GHM Design Bin Hafeez General Contracting & Transport Establishment-Bilbadi Contracting-El Seif Engineering Contracting-Pembinaan SPK Al Mafraq Hospital Abu Dhabi Health Services Company (Seha) Construction 800 Allen -

Manual Title

Department of Municipal Affairs and Transport PO Box 20 Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates © Copyright 2016, by the Department of Municipal Affairs and Transport. All Rights Reserved. This document, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without written permission of the publisher CONGESTION MANAGEMENT POLICY & PROCEDURES TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ................................................................................................................. i List of Figures ..................................................................................................................... v List of Tables ....................................................................................................................... v Glossary ............................................................................................................................. vi 1 Introduction and Summary .......................................................................................... 1 1.1 Overview ................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Mandate of Abu Dhabi DMAT ................................................................................. 1 1.3 Scope of Document ................................................................................................ 3 1.3.1 Purpose, Goal and Objectives ......................................................................... 3 1.3.2 Overall Policy .................................................................................................. -

Adept Environmental Consultancy Company Profile

ADEPT ENVIRONMENTAL CONSULTANCY COMPANY PROFILE M-2, Plot No. C-14, Shabiya-10 (ME-10), Mohammed Bin Zayed City, Abu Dhabi, UAE. Tel.: +971 25548777; Mob.: +971 567535789 Email: [email protected] ; Web Site: https://adepteco.com Contents ABOUT US .......................................................................................................................................... 3 MISSION ............................................................................................................................................. 3 VISION ................................................................................................................................................ 3 OUR VALUES .................................................................................................................................... 3 OUR SERVICES ................................................................................................................................. 4 Environmental Consultancy ........................................................................................................... 4 Ecological Survey ............................................................................................................................ 5 Pollutant Dispersion Modeling ....................................................................................................... 5 Environmental Monitoring ............................................................................................................. 6 Occupational Safety -

Global Report Global Metro Projects 2020.Qxp

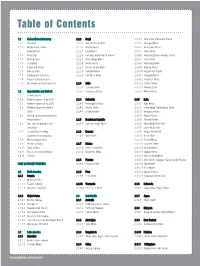

Table of Contents 1.1 Global Metrorail industry 2.2.2 Brazil 2.3.4.2 Changchun Urban Rail Transit 1.1.1 Overview 2.2.2.1 Belo Horizonte Metro 2.3.4.3 Chengdu Metro 1.1.2 Network and Station 2.2.2.2 Brasília Metro 2.3.4.4 Guangzhou Metro Development 2.2.2.3 Cariri Metro 2.3.4.5 Hefei Metro 1.1.3 Ridership 2.2.2.4 Fortaleza Rapid Transit Project 2.3.4.6 Hong Kong Mass Railway Transit 1.1.3 Rolling stock 2.2.2.5 Porto Alegre Metro 2.3.4.7 Jinan Metro 1.1.4 Signalling 2.2.2.6 Recife Metro 2.3.4.8 Nanchang Metro 1.1.5 Power and Tracks 2.2.2.7 Rio de Janeiro Metro 2.3.4.9 Nanjing Metro 1.1.6 Fare systems 2.2.2.8 Salvador Metro 2.3.4.10 Ningbo Rail Transit 1.1.7 Funding and financing 2.2.2.9 São Paulo Metro 2.3.4.11 Shanghai Metro 1.1.8 Project delivery models 2.3.4.12 Shenzhen Metro 1.1.9 Key trends and developments 2.2.3 Chile 2.3.4.13 Suzhou Metro 2.2.3.1 Santiago Metro 2.3.4.14 Ürümqi Metro 1.2 Opportunities and Outlook 2.2.3.2 Valparaiso Metro 2.3.4.15 Wuhan Metro 1.2.1 Growth drivers 1.2.2 Network expansion by 2025 2.2.4 Colombia 2.3.5 India 1.2.3 Network expansion by 2030 2.2.4.1 Barranquilla Metro 2.3.5.1 Agra Metro 1.2.4 Network expansion beyond 2.2.4.2 Bogotá Metro 2.3.5.2 Ahmedabad-Gandhinagar Metro 2030 2.2.4.3 Medellín Metro 2.3.5.3 Bengaluru Metro 1.2.5 Rolling stock procurement and 2.3.5.4 Bhopal Metro refurbishment 2.2.5 Dominican Republic 2.3.5.5 Chennai Metro 1.2.6 Fare system upgrades and 2.2.5.1 Santo Domingo Metro 2.3.5.6 Hyderabad Metro Rail innovation 2.3.5.7 Jaipur Metro Rail 1.2.7 Signalling technology 2.2.6 Ecuador -

Issue No.107/4 December 2014 ,Cfrv

HaRakevet ISSN 0964-8763 Series 28 Issue No.107/4 December 2014 ,cfrv A Quarterly Journal on the Railways of the Middle East Edited and Published by Rabbi Dr. Walter Rothschild PhD Passauer Strasse 4, D-10789 Berlin, Germany e.mail:[email protected] A steam railtour in Tur- key in 2014. The former Kriegslok hauls two TCDD coaches which had been restored and repainted single-handedly by Ali Aksin. (Photo Ali Aksin). Yes, it does rain in Israel, sometimes with a vengeance! Left - Jerusalem, right Ayalon High- way Tel Aviv 107:0 concluded Tuesday morning with the ar- rests of over 5 managers and supervi- sors. According to police, the investiga- EDITORIAL tion – conducted with the full cooperation A bizarre change of emphasis in this issue. After moaning recently about the of Israel Railways CEO, Boaz Zafrir – de- lack of any positive news from most countries in the Middle East, the Editor found lots termined that the sanitation employees of information at Innotrans in Berlin and yet more in relation to proposed conferences colluded for months to commit bribery, (to which he could NOT go) in Dubai and Riyadh, discussing all sorts of fancy, expen- money laundering, fraud, and tax offenses sive and hi-tech projects throughout the region! Of course there is a major disconnect totaling “tens of millions” of shekels. between what one reads in the newspapers and what one sees as a serious discussion In a statement, police said the investi- about building tramways in Kurdistan. So a lot of this is presented here, in this issue, at gation was launched after suspicions were the expense of several historical items which have had to be held over to the next edi- raised that a number of sanitary inspectors tion. -

Secretarial Business Development Mission

SECRETARIAL BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT MISSION Transportation Infrastructure/Multimodal Products and Services Doha, Qatar, and Abu Dhabi and Dubai, United Arab Emirates June 4-9, 2011 I. MISSION DESCRIPTION U.S. Secretary of Commerce Gary Locke will lead a business development mission for multi- modal transportation and infrastructure development products and services to Doha, Qatar and Abu Dhabi and Dubai, United Arab Emirates (UAE) June 4-9, 2011. The mission is designed to contribute to President Obama’s National Export Initiative to achieve the goal of doubling exports over the next five years to support millions of American jobs. This mission will support job creation by increasing exports of products and services that contribute to development projects in these locations. The industry sectors for this mission will include, but are not limited to: multimodal freight transportation systems, products and technologies, including port development, airport development, freight rail systems and technologies, supply chain systems and strategies; mass transportation systems; advanced vehicle technologies and intelligent transportation systems and related services and software; and other relevant products and services. The mission will help U.S. companies already doing business in Qatar or the U.A.E. to increase their current level of exports, business interests and exposure, and will help experienced U.S. exporters, which have not yet done business in Qatar or the U.A.E. to enter these markets in support of job creation in the United States. Participating firms will gain market information, connect with key business and government decision makers, solidify business strategies, and/or advance specific projects. In each of these important sectors, participating U.S. -

Middle East Rail Report

MIDDLE EAST RAIL REPORT The next 10 years will witness unparalleled reform of rail transport within the Middle East. Currently in the GCC, Middle East Rail Investment there are a handful of operational rail lines. However, in the next decade almost every major city will host a state of the UAE: $22.4bn art metro and each country will have a functioning national Key Projects: UAE National Network, Abu Dhabi Metro, rail network. Expansion on this scale, in this time span has Abu Dhabi Light Rail, Dubai Metro, Al Sufouh Tramway never been seen before and the rich opportunities for innovation are attracting attention from across the globe. Qatar: $36.8bn Key Projects: Qatar Regional Passenger Rail, Light Rail The size and scale of railway development projects is vast Transit (LRT), West Bay People Mover, Doha Metro and there are good opportunities for UK companies with international rail capability throughout the supply chain. Saudi Arabia: $44.8bn With our strong heritage in the rail sector, affiliated UK Key Projects: Saudi Bahrain Rail Link, Jeddah Metro, products and services are generally viewed in very high Landbridge, Haramain High-Speed Rail, North South regard throughout the Middle East. Railway Project, Riyadh Metro, Mecca Metro Oman: $15.5bn Market Report Key Projects: National Railway System The Middle East has allocated over $250bn to various Kuwait: $17bn railway projects over the next decade, which will result in Key Projects: Kuwait City Metropolitan Rapid Transit 67,000km of railway tracks throughout the region. System, National Rail Network Investment in on-going rail projects reached over $180bn in early 2013 and the most recent estimates for completed Bahrain: $7.9bn tracks suggest the region currently has under 34,000km. -

RESTRICTED WT/TPR/S/338 27 April 2016

RESTRICTED WT/TPR/S/338 27 April 2016 (16-2331) Page: 1/108 Trade Policy Review Body TRADE POLICY REVIEW REPORT BY THE SECRETARIAT UNITED ARAB EMIRATES This report, prepared for the third Trade Policy Review of the United Arab Emirates, has been drawn up by the WTO Secretariat on its own responsibility. The Secretariat has, as required by the Agreement establishing the Trade Policy Review Mechanism (Annex 3 of the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization), sought clarification from the United Arab Emirates on its trade policies and practices. Any technical questions arising from this report may be addressed to Mr. John Finn (tel: 022 739 5081), Mr. Usman Ali Khilji (tel.: 022 739 6936), and Mr. Samer Seif El Yazal (tel.: 022 739 5459). Document WT/TPR/G/338 contains the policy statement submitted by the United Arab Emirates. Note: This report is subject to restricted circulation and press embargo until the end of the first session of the meeting of the Trade Policy Review Body on the United Arab Emirates. This report was drafted in English. WT/TPR/S/338 • United Arab Emirates - 2 - CONTENTS SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ 6 1 ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT .......................................................................................... 9 1.1 Fiscal Policy ............................................................................................................. 12 1.2 Monetary and Exchange Policy ...................................................................................