PEACE-KEEPING and PEACE-MAKING 9 Peace-Keeping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bab Iv Motif Hias Kerajinan Perak Kotogadang

Kerajinan Perak Kotogadang Sebagai Bagian dari Destinasi Wisata di Sumatera Barat Oleh M. Nasrul Kamal i ii Kerajinan Perak Kotogadang Sebagai Bagian dari Destinasi Wisata di Sumatera Barat Dr. M. Nasrul Kamal, M. Sn. 2018 iii Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia No 19 Tahun 2002 Tentang Hak Cipta Pasal 72 Ketentuan Pidana Saksi Pelanggaran 1. Barangsiapa dengan sengaja dan tanpa hak mengumumkan atau memperbanyak suatu Ciptaan atau memberi izin untuk itu, dipidana dengan pidana penjara palng singkat 1 (satu) bulan dan/atau denda paling sedikit Rp 1.000.000,00 (satu juta rupiah), atau pidana penjara paling lama 7 (tujuh) tahun dan/atau denda paling banyak Rp. 5.000.000.000,00 (lima milyar rupiah) 2. Barangsiapa dengan sengaja menyerahkan, menyiarkan, memamer- kan, mengedarkan, atau menjual kepada umum suatu Ciptaan atau barang hasil pelanggaran Hak Cipta atau Hak Terkait sebagaimana dimaksud dalam ayat (1), dipidana dengan pidana penjara paling lama 5 (lima) tahun dan/atau denda paling banyak Rp 500.000.000,00 (lima ratus juta rupiah). iv Kamal, M. Nasrul Kerajinan Perak Kotogadang sebagai Destinasi Wisata SB Penerbitan dan Percetakan. CV Berkah Prima Alamat: Jalan Datuk Perpatih Nan Sabatang, 287, Air Mati, Solok Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Editor, Nasbahry C., & Rahadian Z. Penerbit CV.Berkah Prima, Padang, 2018 1 (satu) jilid; total halaman 217 + xxiv ISBN: 978-602-5994-06-7 1. Kerajinan 2. Perak 3. Kotogadang, Pariwisata 1. Judul Kerajinan Perak Kotogadang Sebagai Bagian dari Destinasi Wisata di Sumatera Barat Hak Cipta dilindungi oleh undang-undang. Dilarang memperbanyak atau memindahkan sebagian atau seluruh isi buku ini dalam bentuk apapun. -

Report Security Council

REPORT OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL 16 June 1976 -15 June 1977 GENERAL ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL RECORDS: THIRTY-SECOND SESSION SUPPLEMENT No. 2 (A/32/2) UNITED NATIONS - REPORT OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL 16 June 1976 -15 June 1977 GENERAL ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL RECORDS: THIRTY-SECOND SESSION SUPPLEMENT No. 2 (A/32i2) UNITED NATIONS New York, 1977 .----------- ............_..,,__...........iiiiii:""""=~_"""" -=~=>=== NOTE Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters com bined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. Documents of the Security Council (symbol SI . .. ) are normally published in quarterly Supplements of the Official Records of the Security Council. The date of the document indicates the supplement in which it appears or in which infor mation about it is given. The resolutions of the Security Council, numbered in accordance with a system adopted in 1964, are published in yearly volumes of Resolutions and Decisions of the Security Council. The new system, which has been applied retro actively to resolutions adopted before 1 January 1965, became fully operative on that date. [Original: Chinese/English/French/Russian/Spanish] [29 November 1977] CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ..................................................... 1 Part I Questions considered by tbe Security Council under its responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security Chapter 1. QUESTIONS CONCERNING THE MIDDLE EAST ••••••••••.•••••••••••••• 2 A. The situation in the Middle East .. .. ... .. 2 B. The question of the exercise by the Palestinian people of its inalienable rights , " , , .. 7 C. The situation in the occupied Arab territories 8 2. QUESTIONS RELATING TO SOUTHERN AFRICA. •. •• •••• .• .• .• ••• . •• • ••• 10 A. Situation in South Africa: killings and violence by the apartheid regime in South Africa in Soweto and other areas , . -

Peacekeeping Operations and Other Missions - UNEF II

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page 31 Date 14/06/2006 Time 9:23:23 AM S-0899-0003-12-00001 Expanded Number S-0899-0003-12-00001 Title items-in-Middle East - peacekeeping operations and other missions - UNEF II Date Created 21/01/1976 Record Type Archival Item Container s-0899-0003: Peacekeeping - Middle East 1945-1981 Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit ITED NATIONS Distr. GENERAL S/REEA38 (1978) COUNCIL W^W 23 October 1978 RESOLUTION ^38 (1978) Adopted by the Security Council, at its 2091st meeting on -23 October 1976 The Security Council, Recalling its resolutions 338 (1973), 3^0 (1973), 3^1 (1973), 3^6 (1971*), 362 (197^), 368 (1975), 371 (1975), 378 (1975), 396 (1976) and Ul6 (1977), Having considered the report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Ernergency Force (S/12897), Recalling the Secretary-General's view that the situation in the Middle East as a vhole continues to be unstable and potentially dangerous and is likely to remain so unless and until a comprehensive settlement covering all aspects of the Middle East problem can be reached, and his hope that urgent efforts will be pursued by all concerned to tackle the problem in all its aspects, with a view both to maintaining quiet in the region and to arriving at a just and durable peace settlement, as called for by the Security Council in its resolution 338 (1973), 1. Decides to renew the mandate of the United Nations Emergency Force for a period of nine months, that is, until 2U July 1979', 2. -

The Contribution of Two Yohanas Oemar Signs in Contingen Garuda Viii in the Middle East 1978-1979

THE CONTRIBUTION OF TWO YOHANAS OEMAR SIGNS IN CONTINGEN GARUDA VIII IN THE MIDDLE EAST 1978-1979 Fitri Elna, Drs. Ridwan Melay, M.Hum, Bunari, S.Pd., M.Si, Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Phone Number: 082384664451 History Education Program Department of Social Sciences Education Faculty of Teacher Training and Education Riau University Abstract: Yohanas Oemar is a Struggling Learner in Developing Education. In order to fulfill his desire to deepen his knowledge, he willingly tried to persevere and to get what he wanted, as long as the status of students at the University of Riau, he also active in various Campus Organizations, as a student at the Faculty of University of Riau he followed the entrance to the University Student Regiment Riau and became a Member of the Student Regiment. From Member of Student Regiment he got the Opportunity to join Candidate School in Bandung Pangalengan, Yohanas Oemar Graduated School of Candidate with the rank of Second Sergeant, He also get the Opportunity to Contribute to Middle East Peace Sinai joined in Garuda Indonesia Ind Bat Force under UN auspices . And He is in Nobat As Veteran of Peace. This study aims to find out the biography of Yohanas Oemar, Sgt Sergeant's Contribution Two Garuda VIII Contingent as UN Peacekeepers in the Middle East, knowing the end of Yohanas Oemar's Struggle. The method used is the Method of History, namely by using Interview Techniques, Techniques Library Studies, and Documentation. The result of this research is that Yohanas Oemar was born in Strait of Panjang Meranti on 07 Mai 1956 and died on June 25, 2017 is buried in Kahluma Dharma Pahlawan Pekanbaru. -

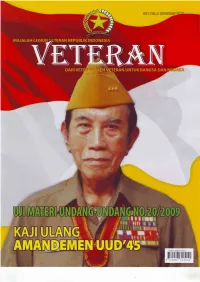

Vol L. No. 2. Desember

Voll. No.2. Desember VeteranMendambakan Damai karena Mengenal Perang -,p VrruRm Salam Redaksi Maialah Veteran No. 2. ini Daftar Isi diterbitkan dengantetap menjelaskan keadazn dan kegiztzn palr^ Veteran SalamRedaksi dan organisasinya Legiun Veteran Amandemen UUD'45 Harus Dikaji Ulang Republik Indonesia, di samping LVRI 54 Tahun menyampaikan pikiran-pikiran dan LVRI SiapkanUji Materi Undang-UndangNo.20l2009 11 hanpan-harapan p^ra Veteran. Pembantaianoleh NICA di TemanggungTahun 1948/1949 1,4 Sejarah Perjuangan Bangsa, baik Pertempuran di Bangka Belitung 18 pembant^t^nNICA di Temanggung, Pertempuran Margarana di Bali 21 Pertempuran di Bangka Belitung dan Desa Marga, Bali serta liputan LVRI Peringati Hari Pahlawan kegiatan-kegiatan dalam nngka Tali Asih untuk Veteran peringatan 10 Nopember 2010 Pahlawanitu ditenrukan oleh Sflaktudan Tempat dengan berbagzt m^c^m kegiatan Veterandalam Gambar 29 sosialnya merupakan beberapa di \Telcome Cambodia 33 antarany^. Lebih khusus adalah Konferensi InternasionalKe-7 WVF di Paris 36 mengenaiHUT LVRI ke-54. Medali WVF untuk D. Ashari 39 Sebagai harapan kami kepada Afganistan pembaca, apabtla mempunyai Hati yang Tenang catatan-catatan, i de-id e, p engalaman- 45 pengalaman atau-pun tulisan-tulisan Hidayat Tokoh di Balik PDRI y^ng bersifat perjuangan, sangat Obrolan Masalah ESB @konomi, Sosialdan Budaya) diharapkan untuk menambah isi HIPVI Tetap Eksis Majalah Veteran terbitan selanjutnya. Ragam Kehidupan Semoga majalah ini dapat SKEP Hymne Veteran memenuhiharapan pan pembaca. Hymne Veteran 55 Himawan Soetanto, Prajurit Kujang Asal Magetan, Telah Tiada 56 Redaksi Gugur Bunga PenerbitDEWAN PIMPINAN PUSAT LVRI, DPP LVRI . GedungVeteran Rl "GrahaPurna Yudha" Jl. Jenderal Sudirman Kav. 50 Jakarta12930 . Telp.(021 ) 5254105,5252449, 25536744 . Fax. (021 ) 5254137Pembinal PenasehatRais Abin - KetuaUmum DPP LVRI, Gatot Suwardi - Wakil KetuaUmum I DPPLVRI, HBL. -

46C3029050c42e1e916cffe5fc65

MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN The coming 2009 elections have contributed quite a force in this year’syear’s activitiesactivities at The Habibie Center. It is the moment for leadership change and acceleration of the consolidation of democracy. A general election is a democratic instrument to select leaders that will serve in both the legislative and executive bodies. It also becomes an important medium for the development of a democratic political culture in society. The 2009 General elections are expected to present a national leader that can guide the nation to solve various problems, overcome crises and usher in a new and better era. Through 2008, in the midst of the extremely dynamic political and economic envi- ronment in Indonesia as well as in the world, The Habibie Center has succeeded in implementing fruitful programs and producing useful research and publications. The consolidation of various institutions under the Center was proven useful for the Center’s 2008 activities and undoubtedly will provide a stronger foundation for future programs and activities. As our commitment for the process of democratization must be held, The Habibie Center has made sure that the routine programs that focused on issues of democ- racy and human rights continued. Issues ranging from politics, legal reform, media, justice and human rights to information technology and education became the focus of the numerous discussions, seminars and workshops held by the Center. These discussions were held not only within the national scope but also internationally with the cooperation of our international partners from Asia, Europe and all over the world. In nine years, The Habibie Center has succeeded in accomplishing a number of important activities and it will continue to conduct activities on efforts to uphold the values and principles of human rights, democracy and good governance in Indonesia. -

International Journal of Education and Social Science Research

International Journal of Education and Social Science Research ISSN 2581-5148 Vol. 4, No. 04; July-Aug 2021 ARRANGEMENT OF THE POSITION OF DIVISION COMMAND FOR HIGHER OFFICERS IN THE MONUSCO UNITED NATIONS MISSION IN THE FRAMEWORK OF STRENGTHENING INDONESIAN DEFENSE DIPLOMACY Soegeng¹, Rodon Pedrason², Sutrimo Sumarlan³ and Tofan Hermawan⁴ 1Graduate School, Faculty of Defense Strategy, Indonesia Defense University, Jl. Sentul - Citeureup, Sentul, Kec. Citeureup, Bogor, Jawa Barat 16810, Indonesia 2Senior Lecturer of Graduate School, Indonesia Defense University, Jl. Sentul - Citeureup, Sentul, Kec. Citeureup, Bogor, Jawa Barat 16810, Indonesia 3Senior Lecturer of Graduate School, Indonesia Defense University, Jl. Sentul - Citeureup, Sentul, Kec. Citeureup, Bogor, Jawa Barat 16810, Indonesia 4Graduate School, Faculty of Defense Strategy, Indonesia Defense University, Jl. Sentul - Citeureup, Sentul, Kec. Citeureup, Bogor, Jawa Barat 16810, Indonesia DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.37500/IJESSR.2021.4407 ABSTRACT Based on the phenomenon, the problem is that the defense diplomacy executing agency has done the best in the United Nations for all missions. However, it creates a gap because there is one mission whose Division Commander has never been served by the TNI, namely MONUSCO. The formulation of research problems on the effect of strengthening Indonesia's defense diplomacy on the arrangement of the position of Division Commander at the United Nations on the MONUSCO mission for TNI High Officers? Basis for Resolution 1925/2010 MONUSCO, Permenlu No.1 / 2017 Roadmap 4,000 peacekeepers, Preamble of the 1945 Constitution, Indonesian Foreign Policy, Law No.34 / 2004 OMSP TNI, Skep Commander TNI No.4 / I / 2007 PMPP TNI. "The sending of UN troops is a real example of a global partnership (Retno Marsudi: 2019). -

The Contribution of Two Yohanas Oemar Signs in Contingen Garuda Viii in the Middle East 1978-1979

THE CONTRIBUTION OF TWO YOHANAS OEMAR SIGNS IN CONTINGEN GARUDA VIII IN THE MIDDLE EAST 1978-1979 Fitri Elna, Drs. Ridwan Melay, M.Hum, Bunari, S.Pd., M.Si, Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Phone Number: 082384664451 History Education Program Department of Social Sciences Education Faculty of Teacher Training and Education Riau University Abstract: Yohanas Oemar is a Struggling Learner in Developing Education. In order to fulfill his desire to deepen his knowledge, he willingly tried to persevere and to get what he wanted, as long as the status of students at the University of Riau, he also active in various Campus Organizations, as a student at the Faculty of University of Riau he followed the entrance to the University Student Regiment Riau and became a Member of the Student Regiment. From Member of Student Regiment he got the Opportunity to join Candidate School in Bandung Pangalengan, Yohanas Oemar Graduated School of Candidate with the rank of Second Sergeant, He also get the Opportunity to Contribute to Middle East Peace Sinai joined in Garuda Indonesia Ind Bat Force under UN auspices . And He is in Nobat As Veteran of Peace. This study aims to find out the biography of Yohanas Oemar, Sgt Sergeant's Contribution Two Garuda VIII Contingent as UN Peacekeepers in the Middle East, knowing the end of Yohanas Oemar's Struggle. The method used is the Method of History, namely by using Interview Techniques, Techniques Library Studies, and Documentation. The result of this research is that Yohanas Oemar was born in Strait of Panjang Meranti on 07 Mai 1956 and died on June 25, 2017 is buried in Kahluma Dharma Pahlawan Pekanbaru. -

Ÿþm Icrosoft W

REPORT REPORT OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL 16 June 1978-15 June 1979 GENERAL ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL RECORDS: THIRTY-FOURTH SESSION SUPPLEMENT No. 2 (A/34/2) UNITED NATIONS New York, 1980 NOTE Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. Documents of the Security Council (symbol S/...) are normally published in quarterly Supplements of the Official Records of the Security Council. The date of the document indicates the supplement in which it appears or in which information about it is given. The resolutions of the Security Council, numbered in accordance with a system adopted in 1964, are published in yearly volumes of Resolutions and D5ecisions of the Security Council. The new system, which has been applied retroactively to resolutions adopted before 1 January 1965, became fully operative on that date. [Original: Chinese/English/FrenchlRussian/Spanish ] 7 December 1979] CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 1 Part I Questions considered by the Security Council under its responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security Chapter I. THE SITUATION IN THE MIDDLE EAST .......................................... 2 A. United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon and developments in the IsraelLebanon sector ...................................................... 2 B. United Nations Emergency Force ..................................... 11 C. United Nations Disengagement Observer Force ......................... II D. The situation in the occupied Arab territories ........................... 13 E. Question of the exercise by the Palestinian people of its inalienable rights.. 17 F. Communications and reports concerning other aspects of the situation in the M iddle East ......................................................... 18 2. THE SITUATION IN CYPRUS .................................................... 19 A. -

ISEAS Staff 103 IV

'· . ' v . ·, " ANNUAL REPORT 1988-89 INSTITUTE OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES SINGAPORE •" - . L5ER5 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies The Institute of Southeast Asian Studies was established as an autonomous organization in May 1968. It is a regional research centre for scholars and other specialists concerned with modern Southeast Asia, particularly the many-faceted problems of stability and security, economic devel opment, and political and social change. The Institute is governed by a twenty-two-member Board of Trustees comprising nominees from the Singapore Government, the National University of Singapore, the various Chambers of Commerce, and professional and civic organizations. A ten-man Executive Committee over sees day-to-day operations; it is chaired by the Director, the Institute's chief academic and administrative officer. The Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Heng Mui Keng Terrace, Singapore 0511. I5'EII5 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies CONTENTS Introduction 1 Board of Trustees 2 Regional Advisory Council 3 Staff 5 Research Fellowships 8 Visiting Fellowships and Associateships 15 Research 15 Regional Programmes 54 Conferences, Seminars, Workshops, and Lectures 73 The Singapore Lecture 84 Publications Unit 88 Library 93 Finance 98 Accommodation 99 Conclusion 99 Appendices I. Board of Trustees 101 II. Committees 102 Ill. ISEAS Staff 103 IV. !SEAS Research Fellows 108 V. Occasional and In-House Seminars 118 VI. !SEAS Titles in Print 121 VII. Donations and Grants Received 135 Auditors' Report 136 Index 149 ASEAN ECONOMIC BULLETIN _ ... =-$t~,.,....- _,_,.,.~~JIU..~- ""' _ _. ....::.~---u-· ............ ~~::r~·~_.-- -w::;~:!'=-:..:=-... JI$Sp;oaAJ;II:I \ 988 p<ll_...-_... .. j$}11_~......--- H•I\~III'l~-~ ___,aJJIOI_~- .,_0!11_. -

Title Items-In-Middle East - Other Countries - General

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page 21 Date 29/06/2006 Time 9:52:52 AM S-0899-0012-08-00001 Expanded Number S-0899-0012-08-00001 Title items-in-Middle East - other countries - general Date Created 04/10/1977 Record Type Archival Item Container S-0899-0012: Peacekeeping - Middle East 1945-1981 Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit ROUTING SLIP FICHE DE TRANSMISSION FROM/L /, /, /-> ' DE: ttu^^L. - 6^^^-K /W-/1£f Room tsio. — No de bureau Extension — Posts Date \ 1 SUC, i&> Itfai, yCCUL> j /f'^GL .j.'~ xfSSkt /L3r«i- & 1 FOR ACTION / POUR SUITE A DONNER FOR APPROVAL POUR APPROBATION FOR SIGNATURE POUR SIGNATURE FOR COMMENTS POUR OBSERVATIONS MAY WE DISCUSS? POURRIONS-NOUS EN PARLER ? YOUR ATTENTION VOTRE ATTENTION AS DISCUSSED COMME CONVENU AS REQUESTED SUITE A VOTRE DEMANDS NOTE AND RETURN NOTER ET RETOURNER FOR INFORMATION POUR INFORMATION COM.6 (2-78) STATEMENT OF THE GOVERNMENT OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AFGHANISTAN (DECEMBER 16, 1981) According to the reports of the international news media the Israeli Knesset in December 14, endorsed a decision taken by the Israeli Cabinet to establish an Israeli administration of the Golan Heights. This move can not be interpreted in any other way but as outright annexation of the territory seized by the Israeli aggressor from Syria in 1967 and illegally occupied since that time in contravention of the relevant resolutions of the United Nations. The Arab peoples, their friends and all progressive people all over the world were stunned by this outrageous decision of Israeli, war-mongering ruling clique taken in complete and flagrant disregard of the relevant security council and other United Nations resolutions related to the situation in the Middle East. -

“VECONAC FOREVER, FOREVER VECONAC” Secretary-General's Report VECONAC 19Th General Assembly Phnom Penh, 10 December 2019

“VECONAC FOREVER, FOREVER VECONAC” Secretary-General’s Report VECONAC 19th General Assembly Phnom Penh, 10 December 2019 Respect to: - His Excellency General KUN KIM, Senior Minister and President of VECONAC - Vice Presidents of VECONAC - Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen In the occasion of VECONAC 19th General Assembly, on behalf of the Secretariat of VECONAC-CAMBODIA 2019, I would like to report the activities of members and VECONAC Secretariat’s performance starting from 01st January to 10th December 2019 as follows: 1. The 32nd Executive Board Meeting and 19th General Assembly 1.1. Honorably and historically, Samdech Akkak Moha Sena Padei Techo Hun Sen, Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Cambodia as President of the Cambodia Veteran Association, highly presides over the opening ceremony of the VECONAC 19th General Assembly at the Peace Palace, Phnom Penh, Kingdom of Cambodia. 1.2. The number of the participants, who are President, Vice Presidents, Delegates of the VECONAC Members and the Working Group of the VECONAC- CAMBODIA Secretariat 2019,totals ……., of which ……. are women. 1.3. The 32nd Executive Board Meeting went successfully and delightfully with …. principles have been achieved for the 19th General Assembly’s review and decision. 2. Updates on the VECONAC Member Associations 1. Veterans Association of Royal Brunei Armed Forces (VARBAF) is led by His Excellency Pehin Dato Padukaraja Major General (R) Dato Paduka Seri Haji Shari Bin Ahmad as President; 2. Cambodia Veteran Association (CVA) is led by Samdech Akkak Moha Sena Padei Techo HUN SEN, Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Cambodia, as President; 3. Veterans Legion of the Republic of Indonesia (LVRI) is led by LT GEN (Rtd) Rais Abin, as President; 4.