Did You Know: Food History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tomato Macaroni & Cheese

Tomato Macaroni & Cheese Eating whole grain foods can increase your fibre intake! Canada’s Food Guide recommends making at least half of your grain products whole grain each day. The fibre content of this hearty oven-baked dish is almost doubled by using whole grain instead of white pasta. Ingredients: 4 cups Whole grain macaroni 1 L 1 Tbsp Vegetable oil 15 mL ⅓ cup Onion, minced or 1 Tbsp (15 mL) onion flakes 75 mL 2 – 14 ounce cans No salt added canned tomatoes, coarsely 2–398 mL cans chopped 1 clove Garlic, minced or ½ tsp (2 mL) garlic powder 1 clove ½ tsp Salt 2 mL ½ tsp Pepper 2 mL 1 tsp Granulated sugar 5 mL 2 cups Cheddar cheese, grated 500 mL Directions: 1. Preheat oven to 375°F (200°C). 2. Cook pasta according to package directions. Drain well and pour into a medium casserole dish. 3. Meanwhile, heat oil in a skillet. Add onion and sauté until soft. Add tomato, garlic, salt, pepper and sugar; cook until it starts to boil. 4. Pour sauce over macaroni and stir lightly. 5. Sprinkle grated cheese over top. 6. Bake uncovered in 375°F (200°C) oven for 30 minutes or until heated through and cheese is melted. Makes 8 servings (1 ¼ cup/ 310 mL/ 285 g) Nutrition Services Tomato Macaroni & Cheese Amount Nutrition Facts Nutrient Claim Per 1/8 of recipe ( 1¼ cup / 310 mL / 285 g) per serving High in fibre 5 g Amount % Daily Value Source of potassium 323 mg Calories 340 High in calcium 264 mg Fat 12 g 18 % Very high in magnesium 64 mg Saturated 6 g 30 % Source of folate 14 mcg + Trans 0 g High in iron 3.2 mg Cholesterol 30 mg Sodium 560 mg 23 % Food Guide Carbohydrate 46 g 15 % Food Group servings per Fibre 5 g 20 % recipe serving Sugars 7 g Vegetables and Fruit 1 Grain Products 2 Protein 16 g Milk and Alternatives ½ Vitamin A 20 % Vitamin C 15 % Meat and Alternatives 0 Calcium 25 % Iron 25 % This is a Choose Sometimes recipe (Mixed Dish–Vegetarian) according to the Alberta Nutrition Guidelines. -

Lunch Back 10-5

STEAMED MUSSELS New Zealand green lip Mussels steamed in a Tomato-Rustica sauce or a white wine and butter sauce served with foccacia bread 7 MILLIONAIRE TACOS The world’s best tacos made with tender, aged-filet and served with fresh pico and tapatio salsa 10 MOB QUESO Spinach, artichokes, shrimp, and Italian sausage in our asiago cheese sauce with pasta chips 8 NACHOS NAPOLI Pasta chips topped with our mob queso sauce, fresh basil, cotija, olives and mild peppers 8 SMOKED SALMON CROSTINI Alaskan Smoked Salmon served on toasted French bread with sun-dried tomatoes and goats cheese. 7 SHRIMPLY DIVINE Six jumbo shrimp sauteed in our own secret herb and butter sauce. Served with foccacia 9 SOUP AND SALAD COMBO Choose a half sized salad from the list below and a cup of today’s soup 6 TAOS SALAD Spring mix, grilled chicken, corn, green chile, black beans, tomatoes, onions, and margarita dressing 8 GRILLED SALMON SALAD Grilled fresh salmon on oriental spring mix with balsamic citrus vinaigrette 10 GRILLED CHICKEN CAESAR Romaine, grilled chicken breast, parmesan, marinated roma tomatoes, and house caesar dressing 7 GOAT CHEESE SALAD Pinion crusted warm goat cheese with creamy lime-basil dressing on exotic field greens 7 RIBEYE STEAK SALAD Grilled beef ribeye, field greens, sauteed onion and bell pepper mix, with a spicy creamy-cucumber dressing 9 SHRIMP AND FENNEL SALAD Fresh grilled jumbo shrimp served with a fennel and balsamic dressing over a spinach and field greens salad 9 QUAIL SALAD Smoked quail with a mescal glaze served on a bed of mixed -

GUIDE to QUICK Family-Style Meals in Times of Anxiety, People Often Turn to Familiar Food to Reassure Themselves and Their Families

A GUIDE TO QUICK Family-Style Meals In times of anxiety, people often turn to familiar food to reassure themselves and their families. Comfort foods are called that for a reason; they let diners relax and eat something they know they’ll enjoy without “ having to make many decisions. Since cities started COVID-19 quarantine procedures, sales of comfort food items have seen a drastic increase with noodles, sandwiches and classic hot dishes leading the way. But what’s in the dish matters less than the memories associated with it, studies have shown. This means the ideal comfort foods are going to vary for different people based on location and ethnicity. Spending some time upgrading popular local comfort foods on your menu and making sure they stand out as winners will set you apart.” Contents 3-7 ITALIAN MEAL BASICS 18 - 22 COMFORT FOOD BASICS 8 - 9 BBQ BASICS 23 - 28 DELI FOOD BASICS 10 MEXICAN BASICS 29 FOOD CONTAINERS 12 - 17 ASIAN BASICS ©2020 All Rights Reserved. Sysco Corporation. 610194 ITALIAN MEAL BASICS PASTAS COOKED DESCRIPTION SUPC PACK SIZE BRAND PASTA MANICOTTI CHEESE 2467603 60 2.7 OZ AREZCLS PASTA MANICOTTI TRDTNL 3504040 60 2.75 OZ AREZCLS PASTA LASAGNA EGG SHEET PRECKD 0222877 40 4 OZ AREZIMP PASTA LASAGNA SHEET FLAT PRCK 3503992 40 4 OZ AREZIMP PASTA SHELL STFD W/CHEESE 2.75 2385847 4 24 CT AREZCLS PASTA RAVIOLI CHS SQUARE 3691714 4 2.5 LB AREZZIO PASTA TORTELLINI BEEF 5276944 3 4 LB AREZCLS PASTA TORTELLINI CHEESE PRCKD 7050222 2 5 LB AREZCLS PASTA TORTELLINI CHEESE 3515954 3 4 LB AREZCLS PASTA TORTELLINI RAINBOW PRCKD -

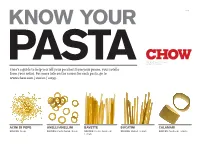

Chart-Of-Pasta-Shapes

KNOW YOUR 1 of 6 Photographs by Chris Rochelle PASTA (Images not actual size) Here’s a guide to help you tell your paccheri from your penne, your rotelle from your rotini. For more info on the sauces for each pasta, go to www.chow.com / stories / 11099. ACINI DI PEPE ANELLI/ANELLINI BAVETTE BUCatINI CALAMARI SAUCES: Soup SAUCES: Pasta Salad, Soup SAUCES: Pesto, Seafood, SAUCES: Baked, Tomato SAUCES: Seafood, Tomato Tomato Know Your Pasta 2 of 6 CAMpanELLE CAPELLINI CASARECCE CAVatELLI CAVaturI SAUCES: Butter/Oil, Cream/ (a.k.a. Angel Hair) SAUCES: Cream/Cheese, SAUCES: Cream/Cheese, SAUCES: Pasta Salad, Cheese, Meat, Pasta Salad, SAUCES: Butter/Oil, Cream/ Meat, Pesto, Seafood, Meat, Pasta Salad, Soup, Vegetable Vegetable Cheese, Pesto, Seafood, Tomato, Vegetable Vegetable Soup, Tomato, Vegetable CONCHIGLIE DItaLINI FarfaLLE FETTUCCINE FREGULA SAUCES: Cream/Cheese, SAUCES: Baked, Pasta Salad, SAUCES: Butter/Oil, Cream/ SAUCES: Butter/Oil, Cream/ SAUCES: Soup, Tomato Meat, Pasta Salad, Pesto, Soup Cheese, Meat, Pasta Salad, Cheese, Meat, Seafood, Tomato, Vegetable Pesto, Seafood, Soup, Tomato, Vegetable Tomato, Vegetable Know Your Pasta 3 of 6 FUSILLI FUSILLI COL BUCO FUSILLI NAPOLEtanI GEMELLI GIGLI SAUCES: Baked, Butter/Oil, SAUCES: Baked, Butter/Oil, SAUCES: Baked, Butter/Oil, SAUCES: Baked, Butter/Oil, SAUCES: Baked, Butter/Oil, Cream/Cheese, Meat, Pasta Cream/Cheese, Meat, Pasta Cream/Cheese, Meat, Pasta Cream/Cheese, Meat, Pasta Meat, Tomato Salad, Pesto, Soup, Tomato, Salad, Pesto, Soup, Tomato, Salad, Pesto, Soup, Tomato, Salad, -

Short Cut Manual

SHORT/CUT™ FOR WINDOWS Table of Contents Thank You.............................................................2 Keys to a Better Cookbook...................................3 Please Remember .................................................5 Installation ...........................................................7 Windows Commands You Should Know..............8 Additional Commands That May Be Useful.....10 The Typing Begins The Welcome Screen.....................................11 Select Your Section Divider Names.............11 The Main Menu ............................................14 Enter/Edit Recipes .......................................16 The Recipe Screen ........................................17 Publisher’s Choice Recipes ..........................22 Tips on Typing Difficult Recipes The Multi-Part Recipe .................................23 The Very Long Ingredient............................26 The Mixed Method Recipe ...........................27 Recipe Notes .................................................28 The Poem ......................................................29 Proofreading .......................................................30 The Final Steps ..................................................32 Appendix The Top Ten (Most Common Mistakes) ......36 Abbreviations................................................37 Dictionary and Brand Names......................38 -1- THANK YOU for selecting the original Short/Cut™ personalized cookbook computer program. This easy-to-follow program will guide you through the -

Download Dining Menu

SIDES APPETIZER MEATBALLS 4 NECK BONES 10 ANTIPASTO PLATE 16 BRUSCHETTA 8 Our signature recipe, 100% beef Slowly braised in red sauce Selection of imported meats and cheeses over Toasted Italian bread topped with diced fresh romaine, olives and tomatoes tomatoes and fresh basil SAUSAGE 4 POLENTA 5 Mild style Creamy Italian style BAKED CLAMS 1/2 - 9 FULL - 15 SMELTS 13 Our signature baked clams drizzled with BRACCIOLE 11 SPINACH 7 MOZZARELLA STICKS 8 house made wine sauce Thinly sliced flank steak rolled with Sautéed with garlic and oil Covered in seasoned breadcrumbs ARTICHOKE CASSEROLE 10 and perfectly fried bread crumbs, onions, pancetta SAUTEED RAPINI 7 Baked artichoke hearts, olive oil, MACARONI & CHEESE 7 MARGHERITA FLATBREAD 11 seasoned bread crumbs Gemelli pasta in creamy four cheese sauce Topped with fresh basil, tomatoes, STUFFED ARTICHOKE 9 and mozzarella Steamed whole artichoke, SAUSAGE & PEPPERS 11 seasoned bread crumbs, melted butter Mild Italian sausage, peppers FRIED CALAMARI 14 SALADS EGGPLANT CONVITO 11 Wild caught calamari, lightly floured, tangy Rolled eggplant stuffed with ricotta cocktail sauce, lemon CHICKEN TENDERS 10 SALMON SALAD 17 SEAFOOD SALAD 18 GRILLED CALAMARI 13 Grilled salmon over mixed greens with red Chargrilled octopus, calamari, black olives, greens Baby squid marinated and char grilled RISOTTO BITES 8 onion, tomatoes, olives, fontinella cheese * Add jumbo shrimp - 3 each and fresh mozzarella. Served with our GRILLED OCTOPUS 14 SEAFOOD PLATTER 24 BROCCOLI SALAD 8 House dressing Fresh octopus, marinated and char grilled Marinated in our House dressing and perfectly grilled. Broccoli florets in lemon vinaigrette Includes calamari, octopus, and jumbo shrimp STEAK SALAD 17 Grilled steak over mixed greens with red CAPRESE SALAD 9 onion, tomatoes, olives, fontinella cheese Vine ripened tomatoes, fresh mozzarella, basil, drizzled with olive oil and fresh mozzarella. -

Nutrition Facts

nutrition nutrition facts RMG 10.19 nutrition ANTIPASTI Calories (kcal) Calories from (kcal) fat (g) Fat (g) Fat Saturated Fatty Trans (g) Acid (mg) Cholesterol Sodium (mg) (g) Carbohydrates FiberDietary (g) (g) Sugars Total (g) Protein Crispy Artichokes 470 400 45 7 0.00 5 480 17 1 2 2 Calamari Fritti 760 490 55 9 0.00 435 700 33 4 7 33 Caprese Salad 510 390 44 18 0.50 100 510 15 2 7 16 Stuffed Mushrooms 510 340 38 13 0.00 60 590 20 3 5 21 Spinach + Artichoke Dip 1,100 540 61 29 1.50 130 1,980 109 7 8 30 Spinach + Artichoke Dip w/Shrimp 1,150 560 62 29 1.50 200 2,290 109 7 8 39 Mushroom Arancini 610 360 40 20 0.50 160 1,040 40 1 2 22 Crispy Brussels Sprouts 370 220 25 4 0.00 0 800 37 8 20 7 Crispy Brussels Sprouts w/Crispy Prosciutto 410 240 28 5 0.00 15 1,080 37 8 20 11 Signature Mac + Cheese Bites 920 630 70 25 1.00 310 1,190 44 2 5 30 Goat Cheese Peppadew Peppers 350 100 11 6 0.00 25 660 56 3 40 6 Bruschetta 670 390 43 9 0.00 25 1,830 55 4 7 17 Baked Prosciutto + Mozzarella 610 330 36 19 0.00 100 1,430 35 1 3 38 Crispy Fresh Mozzarella 820 700 79 16 0.00 145 210 17 1 1 13 soups Calories (kcal) Calories from (kcal) fat (g) Fat (g) Fat Saturated Fatty Trans (g) Acid (mg) Cholesterol Sodium (mg) (g) Carbohydrates FiberDietary (g) (g) Sugars Total (g) Protein Tomato Basil 110 100 8 5 0.50 0 670 9 2 5 2 Roasted Mushroom 180 90 10 5 0.00 25 1,160 19 1 6 6 Italian Herb Soup 70 20 2 1 0.00 5 125 8 2 1 4 Lobster Bisque 320 250 36 16 1.00 85 1,580 14 1 4 5 Tuscan Bean Soup 80 80 9 3 0.00 25 480 8 1 2 7 RMG 10.19 nutrition SALAD Calories (kcal) -

Pasta & Sauce Pairing Suggestions

Pasta & Sauce Pairing Suggestions When pairing a cut of pasta to a type of sauce, the chef is always in charge! There are no rights or wrongs as long as your diners enjoy the dish. However, for those looking for a suggestion or two, the following tips may be helpful. FLAT LONG SHAPES – (Fettuccine, Fettuccine Rigate, Linguine, Linguine Fini) Fettuccine and Fettuccine Rigate are thicker, flat, long shapes, which can withstand extremely robust sauces: • Dairy-based, oil-based or tomato-based sauces • Sauces combined with meat, vegetables, seafood or cheese Linguine and Linguine Fini pair best with traditional pesto. However, other ideal matches include: • Tomato sauces • Oil-based sauces • Fish-based sauces Linguine with Romano Cheese and Black Pepper Fettuccine Fettuccine Linguine Linguine ROUND LONG SHAPES – Rigate Fini (Angel Hair/Capellini, Thin Spaghetti, Spaghetti, Thick Spaghetti, Spaghetti Rigati) Light and dainty, Angel Hair pasta works best with: • Simple, light tomato sauces • Light dairy sauces • Broths, consommés and soups Slightly thicker than Angel Hair, Thin Spaghetti is often used with seafood-based sauces from left to right: Angel Hair/Capellini, Thin Spaghetti, (like tuna) or oil-based sauces, such as: Spaghetti, Thick Spaghetti, Spaghetti Rigati • Light structured sauces that balance the delicacy of this long, thin shape Long and thin, yet not too fine,Spaghetti is one of the more versatile shapes of pasta and pairs well with just about any kind of sauce, including: • Oil-based sauces • Simple tomato sauce with or without meat or vegetables • Fish-based sauces • Carbonara Thicker in diameter than regular Spaghetti, Thick Spaghetti gives a fuller taste to sauces, the following of which are recommended: • Fish-based sauces • Extra-virgin olive oil with fresh aromatic herbs and garlic • Carbonara Rigati, in Italian, means “ridged” and Spaghetti Rigati, because of its extra grooves, tends to hold more sauce than its smooth-shaped counterparts. -

| Hai Lala at Tata Ta Mo Na Atau

|HAI LALA AT TATAUS009883690B2 TA MO NA ATAU HUT (12 ) United States Patent ( 10 ) Patent No. : US 9 , 883 ,690 B2 Weinberg - Sehayek et al. (45 ) Date of Patent: * Feb . 6 , 2018 (54 ) READY - TO - EAT FRESH SPAGHETTI -LIKE (56 ) References Cited FISH PRODUCTS , METHODS OF MANUFACTURE THEREOF U . S . PATENT DOCUMENTS 4 , 704 , 291 A * 11/ 1987 Nagasaki A23L 17 / 70 (71 ) Applicant: GRADIENT AQUACULTURE 426 /513 ( 72 ) Inventors : Noam Weinberg -Sehayek , Shenzhen 4 ,806 , 378 A 2 /1989 Ueno et al. ( CN ) ; Avraham Weinberg , Kiryat Yam (Continued ) ( IL ) FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS ( 73 ) Assignee : GRADIENT AQUACULTURE , CN 101011164 A 8 /2007 Shenzhen (CN ) CULTURE, CN 101209113 A 7 /2008 (Continued ) ( * ) Notice : Subject to any disclaimer , the term of this patent is extended or adjusted under 35 U . S . C . 154 ( b ) by 0 days . OTHER PUBLICATIONS This patent is subject to a terminal dis Rolls B . J . et al ., “ How flavour and appearance affect human claimer . feeding ” , Proceedings of Nutritions Society , Jun . 1982, Great Brit ain , vol. 42 , No. 109 , pp . 109 - 117 . (21 ) Appl. No. : 15 / 262 , 211 (Continued ) (22 ) Filed : Sep . 12 , 2016 Primary Examiner — Robert A Wax Assistant Examiner — Melissa Mercier (65 ) Prior Publication Data US 2017 /0049138 A1 Feb . 23 , 2017 (57 ) ABSTRACT The present invention provides a pasta - like shaped edible Related U . S . Application Data product comprising surimi, fish or portions thereof, prepared (63 ) Continuation - in -part of application No . 14 /601 , 765 , by a process consisting of the steps of: a . chopping frozen surimi to chips ; filed on Jan . 21 , 2015 , which is a continuation - in - part b . -

Call It Macaroni Oklahoma Academic Standards Objective Students Will Use Dry Pasta in a Variety of Math Activities

Call It Macaroni Oklahoma Academic Standards Objective Students will use dry pasta in a variety of math activities. PRE-KINDERGARTEN Number & Operations: 1.1; Background 2.2,4; 3.1. Algebraic Reasoning: Pasta is made from unleavened dough, usually from durum wheat. 1.1,2. Measurement: 2.1,2,3. It comes in a variety of different shapes, sometimes for decoration and Data: 1.1,2 sometimes as a carrier for the different types of sauce and foods. Pasta also Speaking and Listening: includes varieties, such as ravioli and tortellini, which are filled with other R.1,2,3,4; W.1,2. Reading and ingredients, such as ground meat or cheese. Writing Process: R; W. Critical There are hundreds of different shapes of pasta. Examples include Reading and Writing: R.3,4; W spaghetti (thin strings), macaroni (tubes or cylinders), fusilli (swirls), and lasagna (sheets). KINDERGARTEN Pasta is enriched with iron, folate and several other B-vitamins, Number & Operations: including thiamine, riboflavin and niacin. It is even nutritionally enhanced 1.1,2,5,6; 2.1; 3.1. Algebraic with whole wheat or whole grain or fortified with omega-3 fatty acids and Reasoning: 1.1,2. Geometry & additional fiber. Very low in sodium and cholesterol-free when no eggs are Measurement: 1.2,4; 2.1,2,3. used in some varieties, pasta is low in sugar, which means it is digested Data: 1,2,3 more slowly, and provides a slow release of energy without spiking blood Speaking and Listening: sugar levels. R.1,2,3,4; W.1,2. -

Pasta Shapes Catalog

PASTA SHAPES CATALOG Industrial Pasta Extruder Shapes for Models: AEX50 • AEX90/90M • AEX130/30M • AEX440/440M AEX50 AEX90 AEX90M AEX130 AEX130M AEX440 160 GREENFIELD ROAD | LANCASTER, PA 17601 | ARCOBALENOLLC.COM | 717.394.1402 @ARCOBALENOLLC INDUSTRIAL EXTRUDER + MIXER AEX50 AEX90 AEX90M PUSHING BEYOND EXCELLENCE THE ARTISAN THE ARTISAN TWO ARIA LUNA-M LUNA Automatic lasagna OPTIONAL ATTACHMENT sheet spooler Automatic lasagna sheet spooler for AEX30, AEX50, AEX90/90M & AEX130/130M. STANDARD FEATURES • Extra mixer for continuous production STANDARD FEATURES STANDARD FEATURES • Industrial grade with temperature readout • Mixer + Extruder • Mixer + Extruder • Water cooling on extruding chamber • Industrial grade with temperature readout • Industrial grade with temperature readout TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS • Water cooling on extruding chamber • Water cooling on extruding chamber Hourly Production Up to 110 lbs • Electronic cutting knife for short pastas TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS FRONT MIXER Flour Volume 22 lbs Hourly Production Up to 90 lbs Hourly Production Up to 50 lbs FRONT MIXER Production 30 lbs per batch Flour Volume 22 lbs Flour Volume 11 lbs TOP MIXER Flour Volume 18 lbs Mixer Production 30 lbs Mixer Production 15 lbs (flour + liquid) TOP MIXER Production 24 lbs per batch (flour + liquid) Water Line 1/4˝ 60 psi max cold water Water Line 1/4˝ 60 psi max cold water Water Line 1/4˝ 60 psi max cold water Electrical Power 220/3*/60Hz Electrical Power 220/3*/60Hz 2 + 1HP Electrical Power 220/3*/60Hz *3ph must be -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,462.825 B2 Weinberg-Sehayek Et Al

USOO9462825B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,462.825 B2 Weinberg-Sehayek et al. (45) Date of Patent: Oct. 11, 2016 (54) SPAGHETTI-LIKE FISH PRODUCTS, (2013.01); A23L I/296 (2013.01); A23L I/307 METHODS OF MANUFACTURE THEREOF (2013.01); A23 V 2002/00 (2013.01) (58) Field of Classification Search (71) Applicant: GRADIENT AOUACULTURE, None Shenzhen (CN) See application file for complete search history. (72) Inventors: Noam Weinberg-Sehayek, Emek Hefer (56) References Cited (IL); Avraham Weinberg, Kiryat Yam (IL) U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS (73) Assignee: GRADIENT AOUACULTURE, 4,704.291 A *ck 11/1987 Nagasaki .............. A33. Shenzhen (CN) 4,806,378 A 2f1989 Ueno et al. 5,028,444 A 7, 1991 Yamamoto et al. (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this . S. A E. KEY. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 4- 4 - aCal C. a. U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. 2007/0172575 A1* 7, 2007 Gune ............................ 426,641 (21) Appl. No.: 14/601,765 OTHER PUBLICATIONS (22) Filed: Jan. 21, 2015 Omega 6 and 3 in nuts, oils, meats, and fish. Tools to get it right, e a?- posted online May 10, 2011.* O O The Fat Content of Fish, available online 2004. (65) Prior Publication Data Rolls et al. "How Flavour and Appearance Affect Human Feeding”. US 2015/O132434 A1 Mayy 14, 2015 Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, Jun. 1982, pp. 109-117, vol. 41, 109, Great Britain. Related U.S. Application Data (Continued) (63) Continuation-in-part of application No. Primary Examiner — Robert A Wax PCT/IB2014/063294, filed on Jul 22, 2014.