Observations on a Pair of Torrent Ducks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salvadori's Duck of New Guinea

Salvadori’s Duck of New Guinea J . K E A R When Phillips published the fourth volume of to the diving ducks and mergansers. Then his Natural History of the Ducks in 1926, he Mayr (1931a) was able to examine a dead noted that Salvadori’s Duck Salvadorina specimen and found that the sternum and (Anas) waigiuensis was ‘the last to be brought trachea of the male were, although smaller, to light and perhaps the most interesting of the similar to those of the Mallard Anas platy peculiar anatine birds of the world’. It was still rhynchos. As a result, Salvadori’s Duck was practically unknown in 1926; the first moved to the genus A nas. However, as recorded wild nest was not seen until 1959 (H. Niethammer (1952) and Kear (1972) later M. van Deusen, in litt.), and even today the pointed out, the trachea of the Torrent and species has been little studied. Blue Duck are also Anas-like, so that, on this The first specimen was called Salvadorina character, the genera M e rg a n e tta and waigiuensis in 1894 by the Hon. Walter Hymenolaimus could also be eliminated, and Rothschild and by Dr Ernst Hartert, his all three species put with the typical dabbling curator at the Zoological Museum at Tring. ducks. The name was to honour Count Tomasso The present author had already studied the Salvadori, the Italian taxonomist who Blue Duck in New Zealand (Kear, 1972), and specialized both in waterfowl and in the birds was lucky enough to be able to watch of Papua New Guinea. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible. -

References.Qxd 12/14/2004 10:35 AM Page 771

Ducks_References.qxd 12/14/2004 10:35 AM Page 771 References Aarvak, T. and Øien, I.J. 1994. Dverggås Anser Adams, J.S. 1971. Black Swan at Lake Ellesmere. erythropus—en truet art i Norge. Vår Fuglefauna 17: 70–80. Wildl. Rev. 3: 23–25. Aarvak, T. and Øien, I.J. 2003. Moult and autumn Adams, P.A., Robertson, G.J. and Jones, I.L. 2000. migration of non-breeding Fennoscandian Lesser White- Time-activity budgets of Harlequin Ducks molting in fronted Geese Anser erythropus mapped by satellite the Gannet Islands, Labrador. Condor 102: 703–08. telemetry. Bird Conservation International 13: 213–226. Adrian, W.L., Spraker, T.R. and Davies, R.B. 1978. Aarvak, T., Øien, I.J. and Nagy, S. 1996. The Lesser Epornitics of aspergillosis in Mallards Anas platyrhynchos White-fronted Goose monitoring programme,Ann. Rept. in north central Colorado. J. Wildl. Dis. 14: 212–17. 1996, NOF Rappportserie, No. 7. Norwegian Ornitho- AEWA 2000. Report on the conservation status of logical Society, Klaebu. migratory waterbirds in the agreement area. Technical Series Aarvak, T., Øien, I.J., Syroechkovski Jr., E.E. and No. 1.Wetlands International,Wageningen, Netherlands. Kostadinova, I. 1997. The Lesser White-fronted Goose Afton, A.D. 1983. Male and female strategies for Monitoring Programme.Annual Report 1997. Klæbu, reproduction in Lesser Scaup. Unpubl. Ph.D. thesis. Norwegian Ornithological Society. NOF Raportserie, Univ. North Dakota, Grand Forks, US. Report no. 5-1997. Afton, A.D. 1984. Influence of age and time on Abbott, C.C. 1861. Notes on the birds of the Falkland reproductive performance of female Lesser Scaup. -

Engelsk Register

Danske navne på alverdens FUGLE ENGELSK REGISTER 1 Bearbejdning af paginering og sortering af registret er foretaget ved hjælp af Microsoft Excel, hvor det har været nødvendigt at indlede sidehenvisningerne med et bogstav og eventuelt 0 for siderne 1 til 99. Tallet efter bindestregen giver artens rækkefølge på siden. -

Handbook of Waterfowl Behavior: Tribe Anatini (Surface-Feeding Ducks)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Handbook of Waterfowl Behavior, by Paul Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences January 1965 Handbook of Waterfowl Behavior: Tribe Anatini (Surface-feeding Ducks) Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscihandwaterfowl Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Handbook of Waterfowl Behavior: Tribe Anatini (Surface-feeding Ducks)" (1965). Handbook of Waterfowl Behavior, by Paul Johnsgard. 16. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscihandwaterfowl/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Handbook of Waterfowl Behavior, by Paul Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Subfamily Anatinae 125 Aix. During extreme excitement the male will often roll his head on his back, or even bathe. I have not observed Preening-behind-the- wing, but W. von de Wall (pers. comm.) has observed a male per- form it toward a female. Finally, Wing-flapping appears to be used as a display by males, and it is especially conspicuous because each sequence of it is ended by a rapid stretching of both wings over the back in a posture that makes visible the white axillary feathers, which contrast sharply with the black underwing surface. Copulatory behavior. Precopulatory behavior consists of the male swimming up to the female, his neck stretched and his crest de- pressed, and making occasional Bill-dipping movements. He then suddenly begins to perform more vigorous Head-dipping movements, and the female, if receptive, performs similar Bill-dipping or Head- dipping movements. -

Anas Platyrhynchos Global Invasive

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Anas platyrhynchos Anas platyrhynchos System: Freshwater_terrestrial Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Aves Anseriformes Anatidae Common name Synonym Anas oustaleti , Salvadori, 1894 Anas boschas , Linnaeus, 1758 Similar species Summary The mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) is the most common and widely distributed dabbling duck, having a widespread global distribution throughout the northern hemisphere. This migratory species is a highly valued game bird and the source of all domestic ducks with the exception of the Muscovy. Introductions and range expansions of A. platyrhynchos for game purposes pose a threat of competition and hybridization to native waterfowl. Also, recent studies hold the mallard as a likely vector for the highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (HPAIV) (H5N1). view this species on IUCN Red List Species Description Anas platyrhynchos is a medium to large dabbling duck ranging from about 50-60 cm in length and 1-1.3 kg. It is strongly sexually dimorphic. Breeding males bear a distinctive green head, narrow white neck-ring, brown breast, brownish-gray dorsal feathers, pale gray sides and belly, black rump and under tail coverts, white outer tail, and strongly recurved black central tail feathers. Their wings are a pale gray with a distinct iridescent blue upperside and secondaries bordered with white leading and trailing edges, white under-wing coverts, and pale gray undersides. Bills are yellow to olive and legs and feet are orange to red. Females have a broken streaky pattern of buff, white, gray, to black on brown. They have white outer tail feathers and under tail coverts, a white belly, and a prominent dark eyeline. -

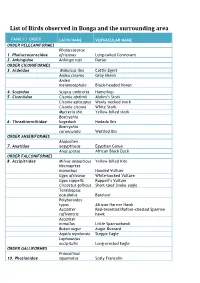

Birds Species in Bonga List

List of Birds observed in Bonga and the surrounding area FAMILY / ORDER LATIN NAME VERNACULAR NAME ORDER PELECANIFORMES Phalacrocorax 1. Phalacrocoracidae africanus Long-tailed Cormorant 2. Anhingidae Anhinga rufa Darter ORDER CICONIIFORMES 3. Ardeidae Bubulcus ibis Cattle Egret Ardea cinerea Grey Heron Ardea melanocephala Black-headed Heron 4. Scopidae Scopus umbretta Hamerkop 5. Ciconiidae Ciconia abdimii Abdim’s Stork Ciconia episcopus Wooly -necked stork Ciconia ciconia White Stork Mycteria ibis Yellow -billed stork Bostrychia 6. Threskiornithidae hagedash Hadada Ibis Bostrychia carunculata Wattled Ibis ORDER ANSERIFORMES Alopochen 7. Anatidae aegyptiacus Egyptian Goose Anas sparsa African Black Duck ORDER FALCONIFORMES 8. Accipitridae Milvus aegypticus Yellow -billed Kite Necrosyrtes monachus Hooded Vulture Gyps africanus White -backed Vulture Gyps ruppellii Ruppell’s Vulture Circaetus gallicus Short -toed Snake -eagle Terathopius ecaudatus Bateleur Polyboroides typus African Harrier Hawk Accipiter Red -breasted/Rufous -chested Sparrow rufiventris hawk Accipiter minullus Little Sparrowhawk Buteo augur Augur Buzzard Aquila nipalensis Steppe Eagle Lophoaetus occipitalis Long-crested Eagle ORDER GALLIFORMES Francolinus 10. Phasianidae squamatus Scaly Francolin FAMILY / ORDER LATIN NAME VERNACULAR NAME Francolinus castaneicollis Chestnut-napped Francolin ORDER GRUIFORMES Balearica 11. Gruidae pavonina Black Crowned Crane Bugeranus carunculatus Wattled crane Ruogetius 12. Rallidae rougetii Rouget’s Rail Podica 13. Heliornithidae senegalensis African Finfoot ORDER CHARADRIIFORMES 14. Scolopacidae Tringa ochropus Green Sandpiper Tringa hypolucos Common Sandpiper ORDER COLUMBIFORMES 15. Columbidae Columba guinea Speckled Pigeon Columba arquatrix African Olive Pigeon (Rameron Pigeon) Streptopelia lugens Dusky (Pink-breasted) Turtle Dove Streptopelia semitorquata Red-eyed Dove Turtur chalcospilos Emerald-spotted Wood Dove Turtur tympanistria Tambourine Dove ORDER CUCULIFORMES 17. Musophagidae Tauraco leucotis White -cheeked Turaco Centropus 18. -

Table Bay Nature Reserve 2Q 2017 Report

TRANSPORT FOR CAPE TOWN ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT Koos Retief Biodiversity Area Manager: Milnerton T: 021 444 0315 E: [email protected] T A B L E B A Y N A T U R E R E S E R V E QUARTERLY REPORT APRIL – JUNE 2017 CONTENTS Pg. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................... 2 2 HIGHLIGHTS & CHALLENGES ............................. 3 3 CONSERVATION PLANNING .............................. 4 4 FLORA .................................................................... 5 5 FAUNA ................................................................... 8 6 SOIL ........................................................................ 11 7 WATER ................................................................... 11 8 FIRE ......................................................................... 13 9 PEOPLE, TOURISM & EDUCATION ..................... 14 10 STAFF ...................................................................... 17 11 LAW ENFORCEMENT ........................................... 18 12 INFRASTRUCTURE & EQUIPMENT ........................ 20 APPENDIX A: MAP OF RESERVE ......................... 21 APPENDIX B: PRESS ARTICLES ............................. 22 The City of Cape Town’s Nature Reserves webpage can be accessed by clicking this link. City of Cape Town | Error! No text of specified style in document. 1 Table Bay Nature Reserve | Tafelbaai-natuurreservaat | ULondolozo lweNdalo lase-Table Bay 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A blue-green algal bloom in Rietvlei resulted in the closure of the water since 17/03/2017. -

Tribe Merganettini (Torrent Duck)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Tribe Merganettini (Torrent Duck) Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Tribe Merganettini (Torrent Duck)" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 11. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Tribe Merganettini (Torrent Duck) h4~~61. Breeding or residential distributions of the Colom- bian ("C") Peruvian ("I"'), and Argentine ("A") torrent ducks. Drawing on preceding page: Peruvian Torrent Duck body, and a contrasting rusty brown on the flanks Torrent Duck and underside of the head, neck, and body. The tail Merganetta armata Gould 1841 and wing patterns are like those of the male, as are the soft-part colors. Juveniles are generally grayish Other vernacular names. None in general English above and white below, with distinctive gray bar use. Sturzbachente (German); canard de torrents ring on the flanks. (French), pato corta-corrientes (Spanish). In the field, torrent ducks are the only waterfowl that inhabit the turbulent Andean streams, and are Subspecies and ranges. -

South Africa: the Southwestern Cape & Kruger August 17–September 1, 2018

SOUTH AFRICA: THE SOUTHWESTERN CAPE & KRUGER AUGUST 17–SEPTEMBER 1, 2018 Leopard LEADER: PATRICK CARDWELL LIST COMPILED BY: PATRICK CARDWELL VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM SOUTH AFRICA: THE SOUTHWESTERN CAPE & KRUGER AUGUST 17–SEPTEMER 1, 2018 By Patrick Cardwell Our tour started in the historical gardens of the Alphen Hotel located in the heart of the Constantia Valley, with vineyards dating back to 1652 with the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck, the first Governor of the Cape. Surrounded by aging oak and poplar trees, this Heritage Site hotel is perfectly situated as a central point within the more rural environs of Cape Town, directly below the towering heights of Table Mountain and close to the internationally acclaimed botanical gardens of Kirstenbosch. DAY 1 A dramatic change in the prevailing weather pattern dictated a ‘switch’ between scheduled days in the itinerary to take advantage of a window of relatively calm sea conditions ahead of a cold front moving in across the Atlantic from the west. Our short drive to the harbor followed the old scenic road through the wine lands and over Constantia Nek to the picturesque and well-wooded valley of Hout (Wood) Bay, so named by the Dutch settlers for the abundance of old growth yellow wood trees that were heavily exploited during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Our skipper was on standby to welcome us on board a stable sport fishing boat with a wraparound gunnel, ideal for all-round pelagic seabird viewing and photographic opportunity in all directions. -

Phylogenetics of a Recent Radiation in the Mallards And

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 70 (2014) 402–411 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Phylogenetics of a recent radiation in the mallards and allies (Aves: Anas): Inferences from a genomic transect and the multispecies coalescent ⇑ Philip Lavretsky a, , Kevin G. McCracken b, Jeffrey L. Peters a a Department of Biological Sciences, Wright State University, 3640 Colonel Glenn Hwy, Dayton, OH 45435, USA b Institute of Arctic Biology, Department of Biology and Wildlife, University of Alaska Museum, 902 N. Koyukuk Dr., Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA article info abstract Article history: Reconstructing species trees by incorporating information from many independent gene trees reduces Received 6 February 2013 the confounding influence of stochastic lineage sorting. Such analyses are particularly important for taxa Revised 5 August 2013 that share polymorphisms due to incomplete lineage sorting or introgressive hybridization. We investi- Accepted 15 August 2013 gated phylogenetic relationships among 14 closely related taxa from the mallard (Anas spp.) complex Available online 27 August 2013 using the multispecies coalescent and 20 nuclear loci sampled from a genomic transect. We also exam- ined how treating recombining loci and hybridizing species influences results by partitioning the data Keywords: using various protocols. In general, topologies were similar among the various species trees, with major Coalescent models clades consistently composed of the same taxa. However, relationships among these clades and among Mallard complex Marker discordance taxa within clades changed among partitioned data sets. Posterior support generally decreased when fil- Recombination tering for recombination, whereas excluding mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) increased posterior support Speciation for taxa known to hybridize with them.