The Taxonomy of the Anatidae—A Behavioural Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Sources Cited

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Sources Cited Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Sources Cited" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Sources Cited Alder, L. P. 1963. The calls and displays of African and In Bellrose, F. C. 1976. Ducks, geese and swans of North dian pygmy geese. In Wildfowl Trust, 14th Annual America. 2d ed. Harrisburg, Pa.: Stackpole. Report, pp. 174-75. Bellrose, F. c., & Hawkins, A. S. 1947. Duck weights in Il Ali, S. 1960. The pink-headed duck Rhodonessa caryo linois. Auk 64:422-30. phyllacea (Latham). Wildfowl Trust, 11th Annual Re Bengtson, S. A. 1966a. [Observation on the sexual be port, pp. 55-60. havior of the common scoter, Melanitta nigra, on the Ali, S., & Ripley, D. 1968. Handbook of the birds of India breeding grounds, with special reference to courting and Pakistan, together with those of Nepal, Sikkim, parties.] Var Fagelvarld 25:202-26. -

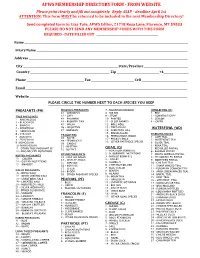

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - from WEBSITE Please Print Clearly and Fill out Completely

APWS MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - FROM WEBSITE Please print clearly and fill out completely. Reply ASAP – deadline April 1st ATTENTION: This form MUST be returned to be included in the next Membership Directory! Send completed form to: Lisa Tate, APWS Editor, 21718 Kesa Lane, Florence, MT 59833 PLEASE DO NOT SEND ANY MEMBERSHIP FUNDS WITH THIS FORM REQUIRED - DATE FILLED OUT ______________________________________________ Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Aviary Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Address _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ City ________________________________________________________________________ State/Province _________________________________ Country ___________________________________________________________ Zip ________________________________+4___________________ Phone ___________________________________________ Fax ________________________________ Cell __________________________________ Email _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Website ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PLEASE CIRCLE THE NUMBER NEXT TO EACH SPECIES YOU KEEP PHEASANTS (PH) PEACOCK-PHEASANTS 7 - MOUNTAIN BAMBOO JUNGLEFOWL -

ILSOLC Bird Checklist

Birding in Seguin Irma Lewis Seguin Outdoor Irma Lewis Seguin, Texas is located in south- central Texas, in an ecological area on Learning Center Seguin Outdoor Learning the boundary of Blackland Prairie to the north and the Post Oak Savannah The Seguin Outdoor Learning Center to the south and east. Most of the Center a 115-acre private, non surrounding land is in agricultural use, primarily cattle grazing, providing a -profit educational facility fairly diverse environment for birds. nestled along Geronimo Creek The Guadalupe River runs through the in northeast Seguin. Our city. Large pecan and cypress trees line the river, including the city park, facilities include a pavilion, Starcke Park, on Bus. 123 South. The natural history center, walking trail in Starcke Park East, along the confluence of Walnut Branch, environmental science center, offers good birding for warblers, blue- amphitheater, ropes course, “Education Through Experience For All Ages” birds and other passerines. Several small reservoirs located along the river nature trail, outdoor class- near town, including Lakes Dunlap, room and pond. Schools, youth McQueeney, and Placid also provide groups, sports teams, clubs, areas for waterfowl. churches and corporations enjoy our peaceful, natural Some species that are common around setting where children and Seguin may be of special interest to citizens of the community can birders from other regions. learn through discovery and Scissor-tailed Flycatchers are unique adventure common during the breeding season. Look for them on fences and telephone experiences. wires anywhere in the countryside around Seguin. Crested Caracaras are The ILSOLC is open to also common in the countryside and are Birding Hours: members, scheduled and especially visible when feeding on Monday-Friday, 8a-5p road-kill carcasses, often in the supervised groups only. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible. -

Genomic Analyses Reveal the Origin of Domestic Ducks and Identify Different

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.03.933069; this version posted February 4, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Genomic analyses reveal the origin of domestic ducks and identify different 2 genetic underpinnings of wild ducks. 3 Rui Liu1,*, Weiqing Liu2,3,*, Enguang Rong1, Lizhi Lu4, Huifang Li5, Li Chen4, Yong 4 Zhao3,6, Huabin Cao7, Wenjie Liu1, Chunhai Chen2, Guangyi Fan2,6,8, Weitao Song6, 5 Huifang Lu3, Yingshuai Sun3, Wenbin Chen2,9, Xin Liu2,6,9, Xun Xu2,6,9, Ning Li1,# 6 1State Key Laboratory for Agrobiotechnology, China Agricultural University, Beijing, 7 100094, China. 2BGI-Shenzhen, Shenzhen 518083, China. 3BGI-Wuhan, Wuhan 8 430075, China. 4Institute of Animal Sciences and Veterinary Medicine, Zhejiang 9 Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Hangzhou 310021, China. 5Institute of Poultry 10 Science of Jiangsu, Yangzhou 225125, China. 6BGI-Qingdao, Qingdao 266555, 11 China. 7Jiangxi Provincial Key Laboratory for Animal Health, Institute of Animal 12 Population Health, College of Animal Science and Technology, Jiangxi Agricultural 13 University, Nanchang 330045, China. 8State Key Laboratory of Quality Research in 14 Chinese Medicine, Institute of Chinese Medical Sciences, University of Macau, 15 Macao, China. 9China National GeneBank-Shenzhen 16 *These authors contributed equally 17 #Corresponding authors: N.L.([email protected]) 18 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.03.933069; this version posted February 4, 2020. -

Waterfowl/Migratory Bird Hunting Regulations

2021 - 2022 Migratory Game A Bird Hunting L Regulations A S K Photo by Jamin Hunter Taylor Graphic Design by Sue Steinacher A The 2021 state duck stamp features a photograph by Jamin Hunter Taylor of a male ring-necked duck (Aythya collaris). Jamin is an Alaska-based nature photographer who specializes in hunting Alaska’s diverse avifauna through the lens of his camera. Ring-necked ducks breed throughout much of Alaska and often congregate into large flocks during fall migration. Unlike most other diving ducks, ring-necked ducks are frequently found in relatively small, shallow ponds and wetlands. The appropriateness of the bird’s common name (and scientific name “collaris”) is often questioned because, in the field, the neck ring is rarely visible. However, in hand it becomes obvious that males of the species do exhibit a chestnut-colored collar at the base of the neck. Despite their name, the species is more easily identified based on their pointed head shape and white ring around the bill. The State of Alaska is an Affirmative Action/Equal Opportunity Employer. Contact [email protected] for alternative formats of this publication. 2 LICENSE AND STAMP REQUIREMENTS Resident Hunters All Alaska residents age 18 or older must possess a hunting license to hunt in Alaska and must carry it while hunting. Resident hunters 60 years old or older may obtain a free, permanent identification card issued by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G). This card replaces the sport fishing, hunting, and trapping licenses. Disabled veterans qualified under AS 16.05.341 may receive a free hunting license. -

Iucn Red Data List Information on Species Listed On, and Covered by Cms Appendices

UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC4/Doc.8/Rev.1/Annex 1 ANNEX 1 IUCN RED DATA LIST INFORMATION ON SPECIES LISTED ON, AND COVERED BY CMS APPENDICES Content General Information ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Species in Appendix I ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Mammalia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Aves ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Reptilia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 Pisces ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Parallel Evolution in the Major Haemoglobin Genes of Eight Species of Andean Waterfowl

Molecular Ecology (2009) doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04352.x Parallel evolution in the major haemoglobin genes of eight species of Andean waterfowl K. G. M C CRACKEN,* C. P. BARGER,* M. BULGARELLA,* K. P. JOHNSON,† S. A. SONSTHAGEN,* J. TRUCCO,‡ T. H. VALQUI,§– R. E. WILSON,* K. WINKER* and M. D. SORENSON** *Institute of Arctic Biology, Department of Biology and Wildlife, and University of Alaska Museum, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA, †Illinois Natural History Survey, Champaign, IL 61820, USA, ‡Patagonia Outfitters, Perez 662, San Martin de los Andes, Neuque´n 8370, Argentina, §Centro de Ornitologı´a y Biodiversidad (CORBIDI), Sta. Rita 117, Urbana Huertos de San Antonio, Surco, Lima 33, Peru´, –Museum of Natural Science, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA, **Department of Biology, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215, USA Abstract Theory predicts that parallel evolution should be common when the number of beneficial mutations is limited by selective constraints on protein structure. However, confirmation is scarce in natural populations. Here we studied the major haemoglobin genes of eight Andean duck lineages and compared them to 115 other waterfowl species, including the bar-headed goose (Anser indicus) and Abyssinian blue-winged goose (Cyanochen cyanopterus), two additional species living at high altitude. One to five amino acid replacements were significantly overrepresented or derived in each highland population, and parallel substitutions were more common than in simulated sequences evolved under a neutral model. Two substitutions evolved in parallel in the aA subunit of two (Ala-a8) and five (Thr-a77) taxa, and five identical bA subunit substitutions were observed in two (Ser-b4, Glu-b94, Met-b133) or three (Ser-b13, Ser-b116) taxa. -

The Role of Habitat Variability and Interactions Around Nesting Cavities in Shaping Urban Bird Communities

The role of habitat variability and interactions around nesting cavities in shaping urban bird communities Andrew Munro Rogers BSc, MSc Photo: A. Rogers A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2018 School of Biological Sciences Andrew Rogers PhD Thesis Thesis Abstract Inter-specific interactions around resources, such as nesting sites, are an important factor by which invasive species impact native communities. As resource availability varies across different environments, competition for resources and invasive species impacts around those resources change. In urban environments, changes in habitat structure and the addition of introduced species has led to significant changes in species composition and abundance, but the extent to which such changes have altered competition over resources is not well understood. Australia’s cities are relatively recent, many of them located in coastal and biodiversity-rich areas, where conservation efforts have the opportunity to benefit many species. Australia hosts a very large diversity of cavity-nesting species, across multiple families of birds and mammals. Of particular interest are cavity-breeding species that have been significantly impacted by the loss of available nesting resources in large, old, hollow- bearing trees. Cavity-breeding species have also been impacted by the addition of cavity- breeding invasive species, increasing the competition for the remaining nesting sites. The results of this additional competition have not been quantified in most cavity breeding communities in Australia. Our understanding of the importance of inter-specific interactions in shaping the outcomes of urbanization and invasion remains very limited across Australian communities. This has led to significant gaps in the understanding of the drivers of inter- specific interactions and how such interactions shape resource use in highly modified environments. -

Phylogeny and Comparative Ecology of Stiff-Tailed Ducks (Anatidae: Oxyurini)

Wilson Bull., 107(2), 1995, pp. 214-234 PHYLOGENY AND COMPARATIVE ECOLOGY OF STIFF-TAILED DUCKS (ANATIDAE: OXYURINI) BRADLEY C. LIVEZEY’ ABSTRACT.-A cladistic analysis of the stiff-tailed ducks (Anatidae: Oxyurini) was con- ducted using 92 morphological characters. The analysis produced one minimum-length, completely dichotomous phylogenetic tree of high consistency (consistency index for infor- mative characters, 0.74). Monophyly of the tribe was supported by 17 unambiguous syna- pomorphies. Within the tribe, Heteronetta (1 species) is the sister-group of other members; within the latter clade (supported by 2 1 unambiguous synapomorphies), Nomonyx (1 species) is the sister-group of Oxyura (6 species) + Biziura (I species). The latter clade is supported by 10 unambiguous synapomorphies. Monophyly of Oxyuru proper is supported by three unambiguous synapomorphies. All branches in the shortest tree except that uniting Oxyuva, exclusive of jumaicensis, were conserved in a majority-rule consensus tree of 1000 boot- strapped replicates. Biziuru and (to a lesser extent) Heteronetta were highly autapomorphic. Modest evolutionary patterns in body mass, reproductive parameters, and sexual dimorphism are evident, with the most marked, correlated changes occurring in Heteronetta and (es- pecially) Biziura. The implications of these evolutionary trends for reproductive ecology and biogeographic patterns are discussed, and a phylogenetic classification of the tribe is presented. Received 27 April 1994, accepted 10 Nov. 1994. The stiff-tailed ducks (Anatidae: Oxyurini) include some of the most distinctive species of waterfowl; among its members are the only obligate nest-parasite (Black-headed Duck; Heteronetta atricapilla) and the spe- cies showing the greatest sexual size dimorphism (Musk Duck; Biziuru lob&z) in the order Anseriformes (Delacour 1959; Johnsgard 1962, 1978; Weller 1968; Livezey 1986).