Salvadori's Duck of New Guinea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible. -

References.Qxd 12/14/2004 10:35 AM Page 771

Ducks_References.qxd 12/14/2004 10:35 AM Page 771 References Aarvak, T. and Øien, I.J. 1994. Dverggås Anser Adams, J.S. 1971. Black Swan at Lake Ellesmere. erythropus—en truet art i Norge. Vår Fuglefauna 17: 70–80. Wildl. Rev. 3: 23–25. Aarvak, T. and Øien, I.J. 2003. Moult and autumn Adams, P.A., Robertson, G.J. and Jones, I.L. 2000. migration of non-breeding Fennoscandian Lesser White- Time-activity budgets of Harlequin Ducks molting in fronted Geese Anser erythropus mapped by satellite the Gannet Islands, Labrador. Condor 102: 703–08. telemetry. Bird Conservation International 13: 213–226. Adrian, W.L., Spraker, T.R. and Davies, R.B. 1978. Aarvak, T., Øien, I.J. and Nagy, S. 1996. The Lesser Epornitics of aspergillosis in Mallards Anas platyrhynchos White-fronted Goose monitoring programme,Ann. Rept. in north central Colorado. J. Wildl. Dis. 14: 212–17. 1996, NOF Rappportserie, No. 7. Norwegian Ornitho- AEWA 2000. Report on the conservation status of logical Society, Klaebu. migratory waterbirds in the agreement area. Technical Series Aarvak, T., Øien, I.J., Syroechkovski Jr., E.E. and No. 1.Wetlands International,Wageningen, Netherlands. Kostadinova, I. 1997. The Lesser White-fronted Goose Afton, A.D. 1983. Male and female strategies for Monitoring Programme.Annual Report 1997. Klæbu, reproduction in Lesser Scaup. Unpubl. Ph.D. thesis. Norwegian Ornithological Society. NOF Raportserie, Univ. North Dakota, Grand Forks, US. Report no. 5-1997. Afton, A.D. 1984. Influence of age and time on Abbott, C.C. 1861. Notes on the birds of the Falkland reproductive performance of female Lesser Scaup. -

Reese--Waterfowl Presentation

Waterfowl – What they are and are not Great variety in sizes, shapes, colors All have webbed feet and bills Sibley reading is great for lots of facts and insights into the group Order Anseriformes Family Anatidae – 154 species worldwide, 44 in NA Subfamily Dendrocygninae – whistling ducks Subfamily Anserinae – geese & swans Subfamily Anatinae - ducks Handout • Indicates those species occurring regularly in ID Ducks = ?? Handout • Indicates those species occurring regularly in ID Ducks = 26 species Geese = ?? Handout • Indicates those species occurring regularly in ID Ducks = 26 species Geese = 6 (3 are rare) Swans = ?? Handout • Indicates those species occurring regularly in ID Ducks = 26 species Geese = 6 Swans = 2 What separates the 3 groups? Ducks - Geese - Swan - What separates the 3 groups? Ducks – smaller, shorter legs & necks Geese – long legs, graze in uplands Swan – shorter legs than geese, long necks, larger size, feed more often in water Non-waterfowl Cranes, rails – beak, rails have lobed feet Coots – bill but lobed feet Grebes – lobed feet Loons – webbed feet but sharp beak Woodcock and snipe – feet not webbed, beaks These are not on handout but are managed by USFWS as are waterfowl On handout: Subfamily Dendrocygninae – whistling ducks – used to be called tree ducks 2 species, more goose-like, longer necks and legs than most ducks, flight is faster than geese, but slower than other ducks Occur along gulf coast and Florida On handout: Subfamily Anserinae – geese and swans Tribe Cygnini – swans – 2 species Tribe Anserini – -

Engelsk Register

Danske navne på alverdens FUGLE ENGELSK REGISTER 1 Bearbejdning af paginering og sortering af registret er foretaget ved hjælp af Microsoft Excel, hvor det har været nødvendigt at indlede sidehenvisningerne med et bogstav og eventuelt 0 for siderne 1 til 99. Tallet efter bindestregen giver artens rækkefølge på siden. -

African Pygmy Goose Scientific Name: Nettapus Auritus Class: Aves Order: Anseriformes Family: Anatidae

African Pygmy Goose Scientific Name: Nettapus auritus Class: Aves Order: Anseriformes Family: Anatidae The African Pygmy Goose is a perching duck from the sub-Saharan Africa area. They are the smallest of Africa’s wildfowl, and one of the smallest in the world. The average weight of a male is 285 grams (10.1 oz) and for the female 260 grams (9.2 oz). Their wingspan is between 142 millimeters (5.6 in) to 165 millimeters (6.5 in). The African pygmy goose has a short bill which extends up the forehead so they resemble geese. The males have a white face with black eye patches. The iridescent black crown extends down the back of the neck. The upper half of the fore neck is white whereas the base of the neck and breast are light chestnut colored. The sixteen tail feathers are black. The wing feathers are black with metallic green iridescence on the coverts. Range The African pygmy goose is found in sub-Saharan Africa and Madagascar. They are known to be nomadic. Habitat They live in slow flowing or stagnant water with a cover of water lilies. This includes inland wetlands, open swamps, river pools, and estuaries. Gestation The female lays 6 to 12 eggs that are incubated for 23 to 26 days. Litter There is usually between 6 and 12 young with each mating. Behavior They live in strong pair bonds that can last over several seasons and their breeding is triggered by rains. Reproduction The African pygmy goose will nest in natural hollows or disused holes of barbets and woodpeckers in trees standing in or close to the water. -

A Natural History of the Ducks

Actx^ssioiis FROM THE Accessions Fl!C).\l TlIK Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Boston Public Library http://www.archive.org/details/naturalhistoryof01phil A NATUEAL HISTORY OF THE DUCKS IN FOUR VOLUMES VOLUME I THE DUCK MARSH A NATURAL HISTORY OF THE DUCKS BY JOHN C. PHILLIPS ASSOCIATE CUBATOR OF BIRDS EST THE MUSEUM OF COMPARATIVE ZOOLOGY AT HARVARD COLLEGE WITH PLATES IN COLOR AND IN BLACK AND WHITE FROM DRAWINGS BY FRANK W. BENSON, ALLAN BROOKS AND LOUIS AGASSIZ FUERTES VOLUME I PLECTROPTERINM, DENDROCYGNINM, ANATINM (m part) BOSTON AND NEW TOEK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY @D|)e Eitiereilie l^xtm CamiiTtlisc 1922 COPYRIGHT, 1922, BY JOHN C. PHILLIPS ALL EIGHTS RESERVED 16 CAMBRIDGE • MASSACHUSETTS PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. ACKNOWLEDGMENT To Mr. William L. Langer, whose knowledge of languages and bibliography- has been indispensable, I owe a lasting debt for many summers of faithful work. Major Allan Brooks and Louis Agassiz Fuertes have given much time and thought to their drawings and have helped me with their gen- eral knowledge of the Duck Tribe. Dr. Glover M. Allen has devoted val- uable time to checking references, and his advice has served to smooth out many wrinkles. To Frank W. Benson, who has done so much in teaching us the decorative value of water-fowl, I owe the frontispiece of this first volume. Lastly I must say a word for the patient and painstaking manner in which many naturalists and sportsmen have answered hun- dreds of long and tedious letters. John C. Phillips Wenham, Massachusetts November, 1922 COPYRIGHT, 1922, BY JOHN C. -

Tribe Merganettini (Torrent Duck)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Tribe Merganettini (Torrent Duck) Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Tribe Merganettini (Torrent Duck)" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 11. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Tribe Merganettini (Torrent Duck) h4~~61. Breeding or residential distributions of the Colom- bian ("C") Peruvian ("I"'), and Argentine ("A") torrent ducks. Drawing on preceding page: Peruvian Torrent Duck body, and a contrasting rusty brown on the flanks Torrent Duck and underside of the head, neck, and body. The tail Merganetta armata Gould 1841 and wing patterns are like those of the male, as are the soft-part colors. Juveniles are generally grayish Other vernacular names. None in general English above and white below, with distinctive gray bar use. Sturzbachente (German); canard de torrents ring on the flanks. (French), pato corta-corrientes (Spanish). In the field, torrent ducks are the only waterfowl that inhabit the turbulent Andean streams, and are Subspecies and ranges. -

Hybridization in the Anatidae and Its Taxonomic Implications

Jan., 1960 25 HYBRIDIZATION IN THE ANATIDAE AND ITS TAXONOMIC IMPLICATIONS By PAUL A. JOHNSGARD Without doubt, waterfowl of the family Anatidae have provided the greatest number and variety of bird hybrids originating from both natural and captive conditions. The recent compilation by Gray (1958) has listed approximately 400 interspecies hybrid combinations in this group, which are far more than have occurred in any other single bird family. Such a remarkable propensity for hybridization in this group provides a great many possibilities for studying the genetics of speciation and the genetics of plum- age and behavior, and it also provides a valuable tool for judging speciesrelationships. It may generally be said that the more closely two speciesare related the more readily these species will hybridize and the more likely they are to produce fertile offspring. In waterfowl, chromosomal imcompatibility and sterility factors are thought to be in- frequent, a circumstance which would favor the large number of hybrids encountered in this group. In addition to this, however, it can probably be safely concluded that the Anatidae are extremely close-knit in an evolutionary sense, for their behavior, anatomy, and other characteristics all indicate a monophyletic origin. It was for these reasons that Delacour and Mayr (194.5)) in their revision of the group, sensibly broadened the species, generic, and subfamilial categories, and in so doing greatly clarified natural relationships. Gray’s compilation, although it provides an incomparable source of hybrid records, does not attempt to synthesize these data into any kind of biologically meaningful pat- tern. For the past several years I have independently been collecting records and infor- mation on waterfowl hybrids for the purpose of obtaining additional evidence for species relationships and in order better to understand problems of isolating mechanisms under natural conditions. -

The Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Aix Galericulata and Tadorna Ferruginea: Bearings on Their Phylogenetic Position in the Anseriformes

The Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Aix galericulata and Tadorna ferruginea: Bearings on Their Phylogenetic Position in the Anseriformes Gang Liu1,2, Lizhi Zhou1,2*,BoLi1,2, Lili Zhang1,2 1 Institute of Biodiversity and Wetland Ecology, School of Resources and Environmental Engineering, Anhui University, Hefei, Anhui, P. R. China, 2 Anhui Biodiversity Information Center, Hefei, Anhui, P. R. China Abstract Aix galericulata and Tadorna ferruginea are two Anatidae species representing different taxonomic groups of Anseriformes. We used a PCR-based method to determine the complete mtDNAs of both species, and estimated phylogenetic trees based on the complete mtDNA alignment of these and 14 other Anseriforme species, to clarify Anseriform phylogenetics. Phylogenetic trees were also estimated using a multiple sequence alignment of three mitochondrial genes (Cyt b, ND2, and COI) from 68 typical species in GenBank, to further clarify the phylogenetic relationships of several groups among the Anseriformes. The new mtDNAs are circular molecules, 16,651 bp (Aix galericulata) and 16,639 bp (Tadorna ferruginea)in length, containing the 37 typical genes, with an identical gene order and arrangement as those of other Anseriformes. Comparing the protein-coding genes among the mtDNAs of 16 Anseriforme species, ATG is generally the start codon, TAA is the most frequent stop codon, one of three, TAA, TAG, and T-, commonly observed. All tRNAs could be folded into canonical cloverleaf secondary structures except for tRNASer (AGY) and tRNALeu (CUN), which are missing the "DHU" arm.Phylogenetic relationships demonstrate that Aix galericula and Tadorna ferruginea are in the same group, the Tadorninae lineage, based on our analyses of complete mtDNAs and combined gene data. -

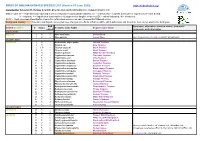

BIRDS of BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) Compiled By: Sebastian K

BIRDS OF BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) https://birdsofbolivia.org/ Compiled by: Sebastian K. Herzog, Scientific Director, Asociación Armonía ([email protected]) Status codes: R = residents known/expected to breed in Bolivia (includes partial migrants); (e) = endemic; NB = migrants not known or expected to breed in Bolivia; V = vagrants; H = hypothetical (observations not supported by tangible evidence); EX = extinct/extirpated; IN = introduced SACC = South American Classification Committee (http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm) Background shading = Scientific and English names that have changed since Birds of Bolivia (2016, 2019) publication and thus differ from names used in the field guide BoB Synonyms, alternative common names, taxonomic ORDER / FAMILY # Status Scientific name SACC English name SACC plate # comments, and other notes RHEIFORMES RHEIDAE 1 R 5 Rhea americana Greater Rhea 2 R 5 Rhea pennata Lesser Rhea Rhea tarapacensis , Puna Rhea (BirdLife International) TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE 3 R 1 Nothocercus nigrocapillus Hooded Tinamou 4 R 1 Tinamus tao Gray Tinamou 5 H, R 1 Tinamus osgoodi Black Tinamou 6 R 1 Tinamus major Great Tinamou 7 R 1 Tinamus guttatus White-throated Tinamou 8 R 1 Crypturellus cinereus Cinereous Tinamou 9 R 2 Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou 10 R 2 Crypturellus obsoletus Brown Tinamou 11 R 1 Crypturellus undulatus Undulated Tinamou 12 R 2 Crypturellus strigulosus Brazilian Tinamou 13 R 1 Crypturellus atrocapillus Black-capped Tinamou 14 R 2 Crypturellus variegatus -

The Mountain Tapir, Endangered 'Flagship' Species of the High Andes

ORYX VOL 30 NO 1 JANUARY 1996 The mountain tapir, endangered 'flagship' species of the high Andes Craig C. Downer The mountain tapir has already disappeared from parts of its range in the high Andes of South America and remaining populations are severely threatened by hunting and habitat destruction. With an estimated population of fewer than 2500 individuals, urgent measures are necessary to secure a future for the species. This paper presents an overview of the species throughout its range as well as some of the main results of the author's studies on tapir ecology. Finally, a plea is made for conservation action in Sangay National Park, which is one of the species's main strongholds. The mountain tapir: an overview throughout its range. There is limited evi- dence to indicate that it may have occurred in The mountain tapir Tapirus pinchaque, was dis- western Venezuela about 20 years ago. covered by the French naturalist Roulin near However, Venezuelan authorities indicate a Sumapaz in the eastern Andes of Colombia total absence of mountain tapir remains from (Cuvier, 1829). The species is poorly known Venezuelan territory, either from the recent or and most information has come from oc- distant past (J. Paucar, F. Bisbal, O. Linares, casional observations or captures in the wild, pers. comms). Northern Peru contains only a reports from indigenous people in the small population (Grimwood, 1969). species's range, and observations and studies In common with many montane forests in zoological parks (Cuvier, 1829; Cabrera and world-wide, those of the Andes are being Yepes, 1940; Hershkovitz, 1954; Schauenberg, rapidly destroyed, causing the decline of the 1969; Bonney and Crotty, 1979).