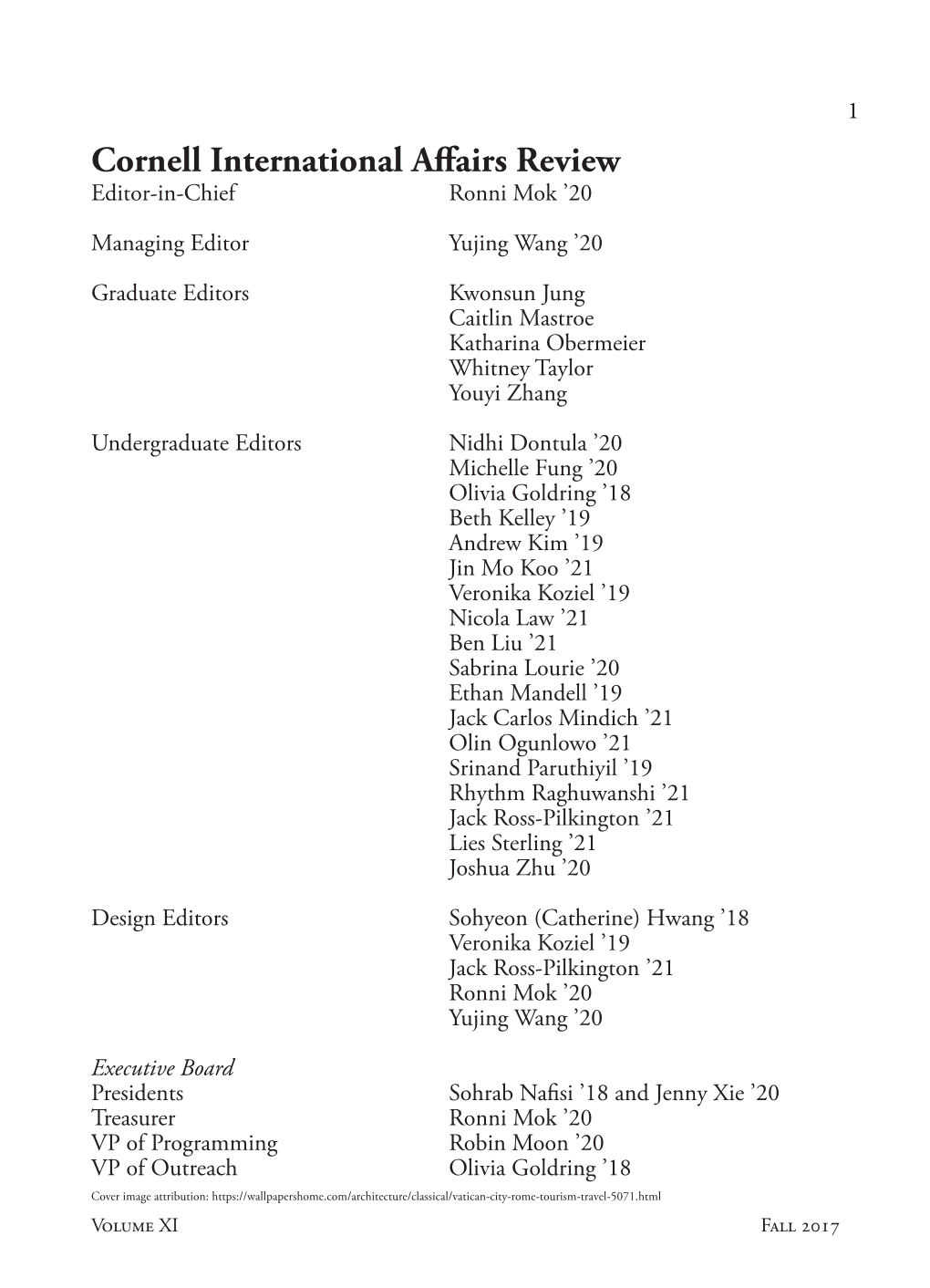

Cornell International Affairs Review Editor-In-Chief Ronni Mok ’20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ad Apostolorum Principis

AD APOSTOLORUM PRINCIPIS ENCYCLICAL OF POPE PIUS XII ON COMMUNISM AND THE CHURCH IN CHINA TO OUR VENERABLE BRETHREN AND BELOVED CHILDREN, THE ARCHBISHOPS, BISHIOPS, OTHER LOCAL ORDINARIES AND CLERGY AND PEOPLE OF CHINA IN PEACE AND COMMUNION WITH THE APOSTOLIC SEE June 29, 1958 Venerable Brethren and Beloved Children, Greetings and Apostolic Benediction. At the tomb of the Prince of the Apostles, in the majestic Vatican Basilica, Our immediate Predecessor of deathless memory, Pius XI, duly consecrated and raised to the fullness of the priesthood, as you well know, "the flowers and . latest buds of the Chinese episcopate."[1] 2. On that solemn occasion he added these words: "You have come, Venerable Brethren, to visit Peter, and you have received from him the shepherd's staff, with which to undertake your apostolic journeys and to gather together your sheep. It is Peter who with great love has embraced you who are in great part Our hope for the spread of the truth of the Gospel among your people."[2] 3. The memory of that allocution comes to Our mind today, Venerable Brethren and dear children, as the Catholic Church in your fatherland is experiencing great suffering and loss. But the hope of our great Predecessor was not in vain, nor did it prove without effect, for new bands of shepherds and heralds of the Gospel have been joined to the first group of bishops whom Peter, living in his Successor, sent to feed those chosen flocks of the Lord. 4. New works and religious undertakings prospered among you despite many obstacles. -

The Four Marks Sample Issue.Pdf

One Holy Catholic Apostolic The Four Marks June 2012 Vol. 7 No. 6 The marks by which men will know His Church are four: $4.75 Month of the Sacred Heart one, holy, catholic, and apostolic AD APOSTOLORUM Ages-old traditions carved in stone PRINCIPIS Encyclical of Pope Pius XII Pope's Butler GRESHAM, Ore., May Voice of the Papacy 30—Vatican leaks are the tip of the iceberg, investigators allege; the real story involves On Communism and the mud-slinging cardinals who Church in China are positioning to be Bene- June 29, 1958 dict's successor. Vatican in- siders are abuzz this week To Our Venerable Brethren following news that Bene- and Beloved Children, the dict's butler, Paolo Gabriele Archbishops, Bishops, other was arrested by magistrates as Local Ordinaries, and Clergy the source behind leaked and People of China in Peace documents, the so-called Va- and Communion with the Apos- tileaks scandal that has tolic See. plagued Rome since 2011. The media seem to be glee- Venerable Brethren and Be- fully speculating about a loved Children, Greetings and deeper more sinister plot. Apostolic Benediction. They may be hoping that they have found the ultimate At the tomb of the Prince of the weapon to destroy the Catho- Apostles, in the majestic Vati- lic Church-- which they think can Basilica, Our immediate they are attacking. Investiga- Predecessor of deathless mem- tors point to one man in par- ory, Pius XI, duly consecrated ticular, the Vatican secretary and raised to the fullness of the of state, Cardinal Tarcisio priesthood, as you well know, Bertone. -

ANASTASIA VALECCE Assistant Professor of Spanish Dept

ANASTASIA VALECCE Assistant Professor of Spanish Dept. of World Languages and Literature, Box 719 450 Cosby Building Spelman College 350 Spelman Lane SW Atlanta, GA 30314 Tlf. (+1) 404 270 5542 [email protected] [email protected] EDUCATION Spring 2013 PhD Emory University, Department of Spanish and Portuguese. Specialization: Latin American Studies with a focus on contemporary Spanish Caribbean, cinema, queer and gender studies, visual culture, performance, and literature. Dissertation Title: Cine y (r)evolución. El neorrealismo italiano en Cuba (1959-1969) [Cinema and (R )evolution. Italian Neorealism in Cuba (1959-1969)] Dissertation Committee: Dr. José Quiroga (Adviser), Dr. Maria Mercedes Carrión, Dr. Mark Sanders, Dr. Juan Carlos Rodríguez. 2006 Siena (Italy) M. A. “Università di Lettere e Filosofia”[University of Literature and Philosophy.] Specialization: Literary Translation and Text Editing from Spanish into Italian. Work as a translator, interpreter, and editor for Gorèe Press, Siena, Italy. Masters Thesis: Translation Project from Spanish into Italian of Mexican piece Yo soy Don Juan para servirle a usted [This is Don Juan Here to Serve You] by Mexican play writer Dante Medina. Thesis Adviser: Dr. Antonio Melis. 2004 Naples (Italy) B. A. “Istituto Universitario l’Orientale,” Foreign Languages and Literature (major in Spanish and English, minor in Portuguese). Honors Thesis: L’immigrazione sirio libanese in Argentina (1850-1950) [The Syrian and Lebanese Immigration to Argentina (1850-1950)] Thesis Adviser: Dr. Angelo Trento. AWARDS 2018 Spring Best Honors Thesis Award. Adviser for Honor thesis La Identidad Racial en la Sociedad Cubana: Una mirada a los Cubanos Afrodescendientes [Racial Identity In Cuban Society: An Overview of Afro Cubans], Spelman College. -

Diplomacia E Religião

Diplomacia e religião-13.indd 1 25/3/2008 14:07:20 Diplomacia e religião-13.indd 2 25/3/2008 14:07:21 Diplomacia e religião-13.indd 3 25/3/2008 14:07:23 © de Anna Carletti 1ª edição: 2008 Direitos reservados desta edição: Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão Capa: Carla M. Luzzatto Revisão: Gláucia Marques Bitencourt Editoração eletrônica: Fernando Piccinini Schmitt Anna Carletti Doutora em História pela Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul Laureada em Línguas e Civilizações Orientais pela Universidade Federal “La Sapienza” de Roma (Itália) Especialista em Língua e Cultura Chinesa junto ao I.S.I.A.O (Instituto Italiano para a África e o Oriente) Pesquisadora Associada do IBECAP - Rio de Janeiro e do NERINT/ILEA da UFRGS. Núcleo de Estratégia e Relações Internacionais (www.ilea.ufrgs.br/nerint; [email protected]) O NERINT foi fundado em 1999 como Grupo de Pesquisa Interdisciplinar junto ao Instituto Latino-Americano de Estudos Avançados da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, visando estudar o reordenamento mundial pós-Guerra Fria e contribuir para a retomada da discussão sobre um projeto nacional para o Brasil, no plano da análise das opções estratégi- cas para a inserção internacional do pais, repensando o tema a partir da perspectiva do mundo em desenvolvimento. Atualmente suas linhas de pesquisa abordam a Cooperação Sul-Sul, os processos de integração da América do Sul, da África Austral e da Ásia Meridional e Oriental, nos campos da segurança, da diplomacia e da economia. O NERINT sedia o Centro de Estudos Brasil-África do Sul (CESUL) e está associado ao Instituto Brasileiro de Estudos sobre China e Ásia-Pacífico (IBECAP-RJ) e co-patrocinou a publicação dessa obra. -

Diplomacia E Religião: Encontros E Desencontros Nas Relações Entre a Santa Sé E a República Popular Da China De 1949 a 2005

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL INSTITUTO DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA DIPLOMACIA E RELIGIÃO: ENCONTROS E DESENCONTROS NAS RELAÇÕES ENTRE A SANTA SÉ E A REPÚBLICA POPULAR DA CHINA DE 1949 A 2005 ANNA CARLETTI Porto Alegre 2007 2 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL INSTITUTO DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA DIPLOMACIA E RELIGIÃO: ENCONTROS E DESENCONTROS NAS RELAÇÕES ENTRE A SANTA SÉ E A REPÚBLICA POPULAR DA CHINA DE 1949 A 2005 ANNA CARLETTI Tese apresentada à banca avaliadora como parte das exigências do Curso de Doutorado em História do Programa de Pós Graduação em História do Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Paulo Gilberto Fagundes Vizentini 3 AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço o meu orientador, o Professor Doutor Paulo G. Fagundes Vizentini, que, desde o início, interessou-se pela minha proposta de pesquisa e ao longo destes anos ofereceu-me sempre valiosas contribuições, incentivando-me em direção a uma pesquisa crítica e construtiva. Com a simplicidade que lhe é característica colocou à minha disposição os seus preciosos conhecimentos, principalmente linhas de interpretação do cenário internacional, que me estimularam a continuar no ambiente acadêmico da pesquisa. Gostaria de agradecer também a todos os professores do Programa de Pós- Graduação de História da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul dos quais recebi uma acolhida atenciosa e delicada. Em particular quero mencionar os Professores Doutores Temístocles Cezar, Silvia Regina Ferraz Petersen, Claúdia Wassermann e Carla Brandalise. Agradeço a todos os meus colegas de curso com os quais compartilhei momentos de entusiasmo e de desânimo, e, sobretudo, ricos debates acadêmicos. -

Seminar on Religious Freedom in China

Seminar on Religious Freedom in China Date: March 2, 2003 (Sunday) Organizer: Justice and Peace Commission of the Hong Kong Catholic Diocese Topics & Speakers: An Analysis of the Current Situation of the Catholic Church in China .................. Father Gianni Criveller (Researcher at the Holy Spirit Study Centre in Hong Kong) Experience Sharing ........................... Father Franco Mella (Kwai Chung New District Christian Grassroots Group) An Analysis of the Changes in Religious Freedom in China in the Past 20 Years ......................... Anthony Lam Sui-ki (Researcher at the Holy Spirit Study Centre in Hong Kong) The Relations Between the Church in Hong Kong and the Church in China ...................................................................... Bishop Joseph Zen Ze-kiun (Bishop of Hong Kong ) Father Gianni Criveller: No Change in Religious Policy The first point that I wish to make is that the Chinese government has made no progress in its religious policy in the last 20 years. The Constitution of 1982 (Article 36) and Document No. 19 of the same year have codified Deng Xiaoping's religious policy. Since then the policy has remained the same: The Party controls religions and the Church; religions must accommodate to the goals of the Communist Party. In other words, religion is tolerated as long as it serves Party policy, which currently is the modernization of the country. Recently, the viewpoints of two Mainland scholars, Pan Yue and Li Pingye have raised hope that there might be some development in the religious policy. I am less optimistic. I do not find Pan Yue and Li Pingye's suggestions really new or positive. Pan Yue suggests that the Party should go beyond condemning religion as "the opium of people". -

Agricultural Reforms, Land Distribution, and Non-Sugar Agricultural Production in Cuba

https://doi.org/10.7896/j.1817 Studies in Agricultural Economics 121 (2019) 13-20 Mario A. GONZALEZ-CORZO* Agricultural Reforms, Land Distribution, and Non-Sugar Agricultural Production in Cuba Since 2007, the Cuban government has introduced a series of agricultural reforms to increase non-sugar agricultural produc- tion and reduce the country’s dependency on food and agricultural imports. The most important agricultural reforms imple- mented in Cuba (so far) include: (a) increases in the prices paid by the state for selected agricultural products, (b) restructuring the Ministry of Agriculture (MINAGRI) and the Ministry of the Sugar Industry (MINAZ), (c) a new agricultural tax system, (d) the authorisation of direct sales and commercialisation of selected agricultural products, (e) micro-credits extended by state- owned banks to private farmers and usufructuaries, and (f) the expansion of usufruct farming. These reforms have contributed to the redistribution of Cuba’s agricultural land from the state to the non-state sector, notable reductions in idle (non-productive) agricultural land, and mixed results in terms of agricultural output. However, they have not been able to sufficiently incentiv- ise output and reduce the country’s high dependency on agricultural and food imports to satisfy the needs of its population. Achieving these long-desired objectives requires the implementation of more profound structural reforms in this vital sector of the Cuban economy. Keywords: Agricultural reforms, Cuban agriculture, Cuban economy, transition economies JEL classifications: Q15, Q18 * Lehman College, The City University of New York, School of Natural and Social Sciences, Department of Economics and Business, Carman Hall, 382, 250 Bedford Park Boulevard West, Bronx, NY 10468. -

Maja De Santa Maria Wikipedia

Maja de santa maria wikipedia Continue MATANAS -- When I read the comment Fragile Lifeline published by Ricardo Ronquillo Bello on Sunday, April 5, I assumed that if it happened in Cuba, it would be the end, even for the cougar that strolled through Santiago de Chile. I can't imagine a boar, a goat or an obedient rabbit walking around St. Louis Causeway, where I live, in the city of Matanzas, because their seconds will be washed away. Aside from the jocosa anecdote, when I reread an excellent journalistic work, I was inundated with feelings of loneliness, and I remembered that just a month ago, when I was going to Varadero to cover measures to prevent a new coronavirus, on the shore of a fast track, near the village of Carbonera, we saw a deer in the bushes, perhaps trying to cross. Although I told a few friends, I then did not assume that this fact could be mentioned in writing, but when my neighbor Ariel Avila Barroso found Maya Santa Maria (Epicrates angulifer) crawling through the matansero viaduct, near the beach of El Tenis, I immediately remembered the text of Ronquillo and warned that in Cuba the same thing could happen. Although social isolation has not behaved on the island as in other countries because people are still behind the chicken, let's imagine that 90 percent of Cubans will stay at home for weeks or months, without raucous music or other discomfort to the animals ... Then yes on our streets you could see a rabbit, a lot more dogs or cats, and maybe sub-territory up to crocodiles, wild boars and deer, or juties that would come down from the bushes. -

People, Communities, and the Catholic Church in China Edited by Cindy Yik-Yi Chu Paul P

CHRISTIANITY IN MODERN CHINA People, Communities, and the Catholic Church in China Edited by Cindy Yik-yi Chu Paul P. Mariani Christianity in Modern China Series Editor Cindy Yik-yi Chu Department of History Hong Kong Baptist University Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong This series addresses Christianity in China from the time of the late Ming and early Qing dynasties to the present. It includes a number of disciplines—history, political science, theology, religious studies, gen- der studies and sociology. Not only is the series inter-disciplinary, it also encourages inter-religious dialogue. It covers the presence of the Catholic Church, the Protestant Churches and the Orthodox Church in China. While Chinese Protestant Churches have attracted much scholarly and journalistic attention, there is much unknown about the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church in China. There is an enor- mous demand for monographs on the Chinese Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church. This series captures the breathtaking phenomenon of the rapid expansion of Chinese Christianity on the one hand, and the long awaited need to reveal the reality and the development of Chinese Catholicism and the Orthodox religion on the other. Christianity in China refects on the tremendous importance of Chinese-foreign relations. The series touches on many levels of research—the life of a single Christian in a village, a city parish, the conficts between converts in a province, the policy of the provincial authority and state-to-state relations. It concerns the infuence of dif- ferent cultures on Chinese soil—the American, the French, the Italian, the Portuguese and so on. -

ABSTRACT Multiple Modernizations, Religious Regulations and Church

ABSTRACT Multiple Modernizations, Religious Regulations and Church Responses: The Rise and Fall of Three “Jerusalems” in Communist China Zhifeng Zhong, Ph.D. Mentor: William A. Mitchell, Ph.D. There is an extensive literature on modernization, regulation and religious change from a global perspective. However, China is usually understudied by the scholars. Numerous studies tackle the puzzle of the rising of Christianity and its implications in China. However they fail to synthesize the multiple dynamics and diverse regional difference. This dissertation approaches the development of Christianity in contemporary China from a regional perspective. By doing a case study on twelve churches in three prefecture cities (Guangzhou, Wenzhou and Nanyang), I examine how different historical processes and factors interacted to shape the uneven development of Christianity under the communist rule. The main research questions are: How did Protestantism survive, transform and flourish under a resilient communism regime? What factors account for the regional variance of the transformation of Christianity? I argue that there are multiple modernizations in China, and they created various cultural frames in the regions. Although the party-state tried to eliminate religion, Protestantism not only survived, but transformed and revived in the Cultural Revolution, which laid the foundation for momentum growth in the reform era. The development of Protestantism in China is dynamic, path-dependent, and contingent on specific settings. Different modernizations, religious regulation, historical legacy and church responses led to the rise and fall of three “Jerusalems” in communist China. Copyright © 2013 by Zhifeng Zhong All rights reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ..................................................................................................... iv LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................... -

Public Practice of Accounting in the Republic of Cuba

University of Mississippi eGrove Haskins and Sells Publications Deloitte Collection 1951 Public Practice of Accounting in the Republic of Cuba Angela M. Lyons Haskins & Sells Foundation American Institute of Accountants Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/dl_hs Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons PUBLIC PRACTICE OF ACCOUNTING IK THE REPUBLIC OF CUBA Prepared for AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ACCOUNTANTS Under the Auspices of HASKINS & SELLS FOUNDATION, INC. By Angela M. Lyons New York, Y.,N. March 1951 CONTENTS Page General Infomation 1 Section I Practice of Accountancy by Nationals ...... 3 Basic Laws and Regulations 3 Concept of Profession ............. 8 Regulatory Authority ............ 10 Who May Practice .. ........ 11 Exercise of the Profession .......... 14 Registration ............ 15 Education of Accountants ............ 20 Some Aspects of Practice . 22 Professional Accountants Engaged in Practice . 23 Professional Accounting Societies ............ 27 II Practice of Accountancy by United States Citizens and Other Non-Nationals ............ 31 Basic Laws and Regulations ............. 31 Qualification of a United States CPA . ... 34 Permanent Practice ............. 36 Isolated Engagements ............ 40 Immigration acquirement............40 Accountants Established in Practice ....... 41 III Treaties and Legislation Pending ............ 42 Proposed Treaty between the United States and Cuba ............ ............42 Treaties between Cuba and Other Countries .... 44 Pending Legislation ............ 45 Appendix Sources of Information ............ REPUBLIC OF CUBA Qssxss^u. Cuba, the largest and most important island of the West Indies, has an area of 44,164 square miles and is comparable in size to the State of Pennsylvania. It is located at the entrance to the Gulf of Mexico, between Worth America and those countries of South America that are bordered by the Caribbean Sea. -

The Great Schism 1054 Pdf

The great schism 1054 pdf Continue Exploring the objective identification of the effects of the East-West split of key points at the turn of the millennium, the Eastern and Western Roman Empire has gradually divided along the religious fault line over the centuries. The division in the Roman world can be marked by the construction of the New Rome of Constantine the Great in Byzantia. The Byzantine iconoclasm, in particular, widened the growing divergence and tension between East and West - the Western Church still strongly supports the use of religious images, although the church at that time was still unified. In response, the pope in the west proclaimed a new emperor in Charles the Great, solidifying the schism and causing outrage in the east. The Empire in the West became known as the Holy Roman Empire. Finally, 1054 AD saw the East-Western schism: the official declaration of the institutional division between the east, the Orthodox Church (now the Eastern Orthodox Church), and the west, in the Catholic Church (now the Roman Catholic Church). The official institutional division in 1054 AD between the Eastern Church of the Byzantine Empire (in the Orthodox Church, now called the Eastern Orthodox Church) and the Western Church of the Holy Roman Empire (in the Catholic Church, now called the Roman Catholic Church). Iconoclasm Destruction or prohibition of religious icons and other images or monuments for religious or political reasons. The East-West divide, also called the Great Divide and The Divide of 1054, was a disconnect between what is now the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic churches, which has lasted since the 11th century.